READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

The Idiocy of Outrage: Sam Harris's Run-ins with Ben Affleck and Noam Chomsky

Too often, we’re convinced by the passion with which someone expresses an idea—and that’s why there’s so much outrage in the news and in other media. Sam Harris has had a particularly hard time combatting outrage with cogent arguments, because he’s no sooner expressed an idea than his interlocutor is aggressively misinterpreting it.

Every time Sam Harris engages in a public exchange of ideas, be it a casual back-and-forth or a formal debate, he has to contend with an invisible third party whose obnoxious blubbering dispels, distorts, or simply drowns out nearly every word he says. You probably wouldn’t be able to infer the presence of this third party from Harris’s own remarks or demeanor. What you’ll notice, though, is that fellow participants in the discussion, be they celebrities like Ben Affleck or eminent scholars like Noam Chomsky, respond to his comments—even to his mere presence—with a level of rancor easily mistakable for blind contempt. This reaction will baffle many in the audience. But it will quickly dawn on anyone familiar with Harris’s ongoing struggle to correct pernicious mischaracterizations of his views that these people aren’t responding to Harris at all, but rather to the dimwitted and evil caricature of him promulgated by unscrupulous journalists and intellectuals.

In his books on religion and philosophy, Harris plies his unique gift for cutting through unnecessary complications to shine a direct light on the crux of the issue at hand. Topics that other writers seem to go out of their way to make abstruse he manages to explore with jolting clarity and refreshing concision. But this same quality to his writing which so captivates his readers often infuriates academics, who feel he’s cheating by breezily refusing to represent an issue in all its grand complexity while neglecting to acknowledge his indebtedness to past scholars. That he would proceed in such a manner to draw actual conclusions—and unorthodox ones at that—these scholars see as hubris, made doubly infuriating by the fact that his books enjoy such a wide readership outside of academia. So, whether Harris is arguing on behalf of a scientific approach to morality or insisting we recognize that violent Islamic extremism is motivated not solely by geopolitical factors but also by straightforward readings of passages in Islamic holy texts, he can count on a central thread of the campaign against him consisting of the notion that he’s a journeyman hack who has no business weighing in on such weighty matters.

Sam Harris

Philosophers and religious scholars are of course free to challenge Harris’s conclusions, and it’s even possible for them to voice their distaste for his style of argumentation without necessarily violating any principles of reasoned debate. However, whenever these critics resort to moralizing, we must recognize that by doing so they’re effectively signaling the end of any truly rational exchange. For Harris, this often means a substantive argument never even gets a chance to begin. The distinction between debating morally charged topics on the one hand, and condemning an opponent as immoral on the other, may seem subtle, or academic even. But it’s one thing to argue that a position with moral and political implications is wrong; it’s an entirely different thing to become enraged and attempt to shout down anyone expressing an opinion you deem morally objectionable. Moral reasoning, in other words, can and must be distinguished from moralizing. Since the underlying moral implications of the issue are precisely what are under debate, giving way to angry indignation amounts to a pulling of rank—an effort to silence an opponent through the exercise of one’s own moral authority, which reveals a rather embarrassing sense of one’s own superior moral standing.

Unfortunately, it’s far too rarely appreciated that a debate participant who gets angry and starts wagging a finger is thereby demonstrating an unwillingness or an inability to challenge a rival’s points on logical or evidentiary grounds. As entertaining as it is for some to root on their favorite dueling demagogue in cable news-style venues, anyone truly committed to reason and practiced in its application realizes that in a debate the one who loses her cool loses the argument. This isn’t to say we should never be outraged by an opponent’s position. Some issues have been settled long enough, their underlying moral calculus sufficiently worked through, that a signal of disgust or contempt is about the only imaginable response. For instance, if someone were to argue, as Aristotle did, that slavery is excusable because some races are naturally subservient, you could be forgiven for lacking the patience to thoughtfully scrutinize the underlying premises. The problem, however, is that prematurely declaring an end to the controversy and then moving on to blanket moral condemnation of anyone who disagrees has become a worryingly common rhetorical tactic. And in this age of increasingly segmented and polarized political factions it’s more important than ever that we check our impulse toward sanctimony—even though it’s perhaps also harder than ever to do so.

Once a proponent of some unpopular idea starts to be seen as not merely mistaken but dishonest, corrupt, or bigoted, then playing fair begins to seem less obligatory for anyone wishing to challenge that idea. You can learn from casual Twitter browsing or from reading any number of posts on Salon.com that Sam Harris advocates a nuclear first strike against radical Muslims, supported the Bush administration’s use of torture, and carries within his heart an abiding hatred of Muslim people, all billion and a half of whom he believes are virtually indistinguishable from the roughly 20,000 militants making up ISIS. You can learn these things, none of which is true, because some people dislike Harris’s ideas so much they feel it’s justifiable, even imperative, to misrepresent his views, lest the true, more reasonable-sounding versions reach a wider receptive audience. And it’s not just casual bloggers and social media mavens who feel no qualms about spreading what they know to be distortions of Harris’s views; religious scholar Reza Aslan and journalist Glenn Greenwald both saw fit to retweet the verdict that he is a “genocidal fascist maniac,” accompanied by an egregiously misleading quote as evidence—even though Harris had by then discussed his views at length with both of these men.

It’s easy to imagine Ben Affleck doing some cursory online research to prep for his appearance on Real Time with Bill Maher and finding plenty of savory tidbits to prejudice him against Harris before either of them stepped in front of the cameras. But we might hope that a scholar of Noam Chomsky’s caliber wouldn’t be so quick to form an opinion of someone based on hearsay. Nonetheless, Chomsky responded to Harris’s recent overture to begin an email exchange to help them clear up their misconceptions about each other’s ideas by writing: “Perhaps I have some misconceptions about you. Most of what I’ve read of yours is material that has been sent to me about my alleged views, which is completely false”—this despite Harris having just quoted Chomsky calling him a “religious fanatic.” We must wonder, where might that characterization have come from if he’d read so little of Harris’s work?

Political and scholarly discourse would benefit immensely from a more widespread recognition of our natural temptation to recast points of intellectual disagreement as moral offenses, a temptation which makes it difficult to resist the suspicion that anyone espousing rival beliefs is not merely mistaken but contemptibly venal and untrustworthy. In philosophy and science, personal or so-called ad hominem accusations and criticisms are considered irrelevant and thus deemed out of bounds—at least in principle. But plenty of scientists and academics of every stripe routinely succumb to the urge to moralize in the midst of controversy. Thus begins the lamentable process by which reasoned arguments are all but inevitably overtaken by competing campaigns of character assassination. In service to these campaigns, we have an ever growing repertoire of incendiary labels with ever lengthening lists of criteria thought to reasonably warrant their application, so if you want to discredit an opponent all that’s necessary is a little creative interpretation, and maybe some selective quoting.

The really tragic aspect of this process is that as scrupulous and fair-minded as any given interlocutor may be, it’s only ever a matter of time before an unpopular message broadcast to a wider audience is taken up by someone who feels duty-bound to kill the messenger—or at least to besmirch the messenger’s reputation. And efforts at turning thoughtful people away from troublesome ideas before they ever even have a chance to consider them all too often meet with success, to everyone’s detriment. Only a small percentage of unpopular ideas may merit acceptance, but societies can’t progress without them.

Once we appreciate that we’re all susceptible to this temptation to moralize, the next most important thing for us to be aware of is that it becomes more powerful the moment we begin to realize ours are the weaker arguments. People in individualist cultures already tend to more readily rate themselves as exceptionally moral than as exceptionally intelligent. Psychologists call this tendency the Muhammed Ali effect (because the famous boxer once responded to a journalist’s suggestion that he’d purposely failed an Army intelligence test by quipping, “I only said I was the greatest, not the smartest”). But when researchers Jens Möller and Karel Savyon had study participants rate themselves after performing poorly on an intellectual task, they found that the effect was even more pronounced. Subjects in studies of the Muhammed Ali effect report believing that moral traits like fairness and honesty are more socially desirable than intelligence. They also report believing these traits are easier for an individual to control, while at the same time being more difficult to measure. Möller and Savyon theorize that participants in their study were inflating their already inflated sense of their own moral worth to compensate for their diminished sense of intellectual worth. While researchers have yet to examine whether this amplification of the effect makes people more likely to condemn intellectual rivals on moral grounds, the idea that a heightened estimation of moral worth could make us more likely to assert our moral authority seems a plausible enough extrapolation from the findings.

That Ben Affleck felt intimated by the prospect of having to intelligently articulate his reasons for rejecting Harris’s positions, however, seems less likely than that he was prejudiced to the point of outrage against Harris sometime before encountering him in person. At one point in the interview he says, “You’re making a career out of ISIS, ISIS, ISIS,” a charge of pandering that suggests he knows something about Harris’s work (though Harris doesn't discuss ISIS in any of his books). Unfortunately, Affleck’s passion and the sneering tone of his accusations were probably more persuasive for many in the audience than any of the substantive points made on either side. But, amid Affleck’s high dudgeon, it’s easy to sift out views that are mainstream among liberals. The argument Harris makes at the outset of the segment that first sets Affleck off—though it seemed he’d already been set off by something—is in fact a critique of those same views. He says,

When you want to talk about the treatment of women and homosexuals and freethinkers and public intellectuals in the Muslim world, I would argue that liberals have failed us. [Affleck breaks in here to say, “Thank God you’re here.”] And the crucial point of confusion is that we have been sold this meme of Islamophobia, where every criticism of the doctrine of Islam gets conflated with bigotry toward Muslims as people.

This is what Affleck says is “gross” and “racist.” The ensuing debate, such as it is, focuses on the appropriateness—and morality—of criticizing the Muslim world for crimes only a subset of Muslims are guilty of. But how large is that subset?

Harris (along with Maher) makes two important points: first, he states over and over that it’s Muslim beliefs he’s criticizing, not the Muslim people, so if a particular Muslim doesn’t hold to the belief in question he or she is exempt from the criticism. Harris is ready to cite chapter and verse of Islamic holy texts to show that the attitudes toward women and homosexuals he objects to aren’t based on the idiosyncratic characters of a few sadistic individuals but are rather exactly what’s prescribed by religious doctrine. A passage from his book The End of Faith makes the point eloquently.

It is not merely that we are war with an otherwise peaceful religion that has been “hijacked” by extremists. We are at war with precisely the vision of life that is prescribed to all Muslims in the Koran, and further elaborated in the literature of the hadith, which recounts the sayings and actions of the Prophet. A future in which Islam and the West do not stand on the brink of mutual annihilation is a future in which most Muslims have learned to ignore most of their canon, just as most Christians have learned to do. (109-10)

But most secularists and moderate Christians in the U.S. have a hard time appreciating how seriously most Muslims take their Koran. There are of course passages in the Bible that are simply obscene, and Christians have certainly committed their share of atrocities at least in part because they believed their God commanded them to. But, whereas almost no Christians today advocate stoning their brothers, sisters, or spouses to death for coaxing them to worship other gods (Deuteronomy 13:6 8-15), a significant number of people in Islamic populations believe apostates and “innovators” deserve to have their heads lopped off.

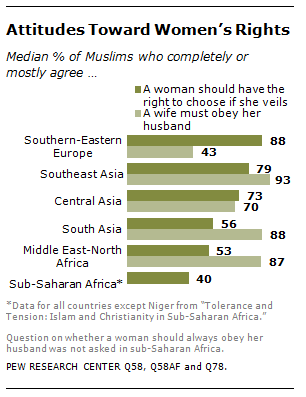

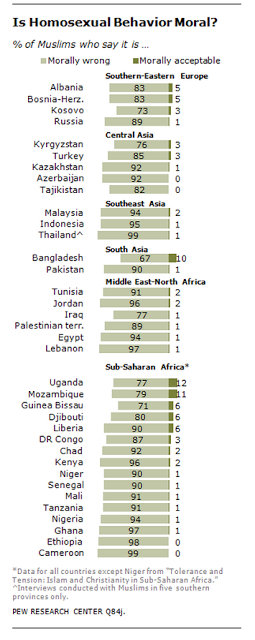

The second point Harris makes is that, while Affleck is correct in stressing how few Muslims make up or support the worst of the worst groups like Al Qaeda and ISIS, the numbers who believe women are essentially the property of their fathers and husbands, that homosexuals are vile sinners, or that atheist bloggers deserve to be killed are much higher. “We have to empower the true reformers in the Muslim world to change it,” as Harris insists. The journalist Nicholas Kristof says this is a mere “caricature” of the Muslim world. But Harris’s goal has never been to promote a negative view of Muslims, and he at no point suggests his criticisms apply to all Muslims, all over the world. His point, as he stresses multiple times, is that Islamic doctrine is inspiring large numbers of people to behave in appalling ways, and this is precisely why he’s so vocal in his criticisms of those doctrines.

Part of the difficulty here is that liberals (including this one) face a dilemma anytime they’re forced to account for the crimes of non-whites in non-Western cultures. In these cases, their central mission of standing up for the disadvantaged and the downtrodden runs headlong into their core principle of multiculturalism, which makes it taboo for them to speak out against another society’s beliefs and values. Guys like Harris are permitted to criticize Christianity when it’s used to justify interference in women’s sexual decisions or discrimination against homosexuals, because a white Westerner challenging white Western culture is just the system attempting to correct itself. But when Harris speaks out against Islam and the far worse treatment of women and homosexuals—and infidels and apostates—it prescribes, his position is denounced as “gross” and “racist” by the likes of Ben Affleck, with the encouragement of guys like Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald. A white American male casting his judgment on a non-Western belief system strikes them as the first step along the path to oppression that ends in armed invasion and possibly genocide. (Though, it should be noted, multiculturalists even attempt to silence female critics of Islam from the Muslim world.)

The biggest problem with this type of slippery-slope presumption isn’t just that it’s sloppy thinking—rejecting arguments because of alleged similarities to other, more loathsome ideas, or because of some imagined consequence should those ideas fall into the wrong hands. The biggest problem is that it time and again provides a rationale for opponents of an idea to silence and defame anyone advocating it. Unless someone is explicitly calling for mistreatment or aggression toward innocents who pose no threat, there’s simply no way to justify violating anyone’s rights to free inquiry and free expression—principles that should supersede multiculturalism because they’re the foundation and guarantors of so many other rights. Instead of using our own delusive moral authority in an attempt to limit discourse within the bounds we deem acceptable, we have a responsibility to allow our intellectual and political rivals the space to voice their positions, trusting in our fellow citizens’ ability to weigh the merits of competing arguments.

But few intellectuals are willing to admit that they place multiculturalism before truth and the right to seek and express it. And, for those who are reluctant to fly publically into a rage or to haphazardly apply any of the growing assortment of labels for the myriad varieties of bigotry, there are now a host of theories that serve to reconcile competing political values. The multicultural dilemma probably makes all of us liberals too quick to accept explanations of violence or extremism—or any other bad behavior—emphasizing the role of external forces, whether it’s external to the individual or external to the culture. Accordingly, to combat Harris’s arguments about Islam, many intellectuals insist that religion simply does not cause violence. They argue instead that the real cause is something like resource scarcity, a history of oppression, or the prolonged occupation of Muslim regions by Western powers.

If the arguments in support of the view that religion plays a negligible role in violence were as compelling as proponents insist they are, then it’s odd that they should so readily resort to mischaracterizing Harris’s positions when he challenges them. Glenn Greenwald, a journalist who believes religion is such a small factor that anyone who criticizes Islam is suspect, argues his case against Harris within an almost exclusively moral framework—not is Harris right, but is he an anti-Muslim? The religious scholar Reza Aslan quotes Harris out of context to give the appearance that he advocates preemptive strikes against Muslim groups. But Aslan’s real point of disagreement with Harris is impossible to pin down. He writes,

After all, there’s no question that a person’s religious beliefs can and often do influence his or her behavior. The mistake lies in assuming there is a necessary and distinct causal connection between belief and behavior.

Since he doesn’t explain what he means by “necessary and distinct,” we’re left with little more than the vague objection that religion’s role in motivating violence is more complex than some people seem to imagine. To make this criticism apply to Harris, however, Aslan is forced to erect a straw man—and to double down on the tactic after Harris has pointed out his error, suggesting that his misrepresentation is deliberate.

Few commenters on this debate appreciate just how radical Aslan’s and Greenwald’s (and Karen Armstrong’s) positions are. The straw men notwithstanding, Harris readily admits that religion is but one of many factors that play a role in religious violence. But this doesn’t go far enough for Aslan and Greenwald. While they acknowledge religion must fit somewhere in the mix, they insist its role is so mediated and mixed up with other factors that its influence is all but impossible to discern. Religion in their minds is a pure social construct, so intricately woven into the fabric of a culture that it could never be untangled. As evidence of this irreducible complexity, they point to the diverse interpretations of the Koran made by the wide variety of Muslim groups all over the world. There’s an undeniable kernel of truth in this line of thinking. But is religion really reconstructed from scratch in every culture?

One of the corollaries of this view is that all religions are essentially equal in their propensity to inspire violence, and therefore, if adherents of one particular faith happen to engage in disproportionate levels of violence, we must look to other cultural and political factors to explain it. That would also mean that what any given holy text actually says in its pages is completely immaterial. (This from a scholar who sticks to a literal interpretation of a truncated section of a book even though the author assures him he’s misreading it.) To highlight the absurdity of this idea, Harris likes to cite the Jains as an example. Mahavira, a Jain patriarch, gave this commandment: “Do not injure, abuse, oppress, enslave, insult, torment, or kill any creature or living being.” How plausible is the notion that adherents of this faith are no more and no less likely to commit acts of violence than those whose holy texts explicitly call for them to murder apostates? “Imagine how different our world might be if the Bible contained this as its central precept” (23), Harris writes in Letter to a Christian Nation.

Since the U.S. is in fact a Christian nation, and since it has throughout its history displaced, massacred, invaded, occupied, and enslaved people from nearly every corner of the globe, many raise the question of what grounds Harris, or any other American, has for judging other cultures. And this is where the curious email exchange Harris began with the linguist and critic of American foreign policy Noam Chomsky takes up. Harris reached out to Chomsky hoping to begin an exchange that might help to clear up their differences, since he figured they have a large number of readers in common. Harris had written critically of Chomsky’s book about 9/11 in End of Faith, his own book on the topic of religious extremism written some time later. Chomsky’s argument seems to have been that the U.S. routinely commits atrocities on a scale similar to that of 9/11, and that the Al Qaeda attacks were an expectable consequence of our nation’s bullying presence in global affairs. Instead of dealing with foreign threats then, we should be concentrating our efforts on reforming our own foreign policy. But Harris points out that, while it’s true the U.S. has caused the deaths of countless innocents, the intention of our leaders wasn’t to kill as many people as possible to send a message of terror, making such actions fundamentally different from those of the Al Qaeda terrorists.

The first thing to note in the email exchange is that Harris proceeds on the assumption that any misunderstanding of his views by Chomsky is based on an honest mistake, while Chomsky immediately takes for granted that Harris’s alleged misrepresentations are deliberate (even though, since Harris sends him the excerpt from his book, that would mean he’s presenting the damning evidence of his own dishonesty). In other words, Chomsky switches into moralizing mode at the very outset of the exchange. The substance of the disagreement mainly concerns the U.S.’s 1998 bombing of the al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Sudan. According to Harris’s book, Chomsky argues this attack was morally equivalent to the attacks by Al Qaeda on 9/11. But in focusing merely on body counts, Harris charges that Chomsky is neglecting the far more important matter of intention.

Noam Chomsky

Chomsky insists after reading the excerpt, however, that he never claimed the two attacks were morally equivalent, and that furthermore he in fact did consider, and write at length about, the intentions of the Clinton administration officials who decided to bomb al-Shifa—just not in the book cited by Harris. In this other book, which Chomsky insists Harris is irresponsible for not having referenced, he argues that the administration’s claim that it received intelligence about the factory manufacturing chemical weapons was a lie and that the bombing was actually meant as retaliation for an earlier attack on the U.S. Embassy. Already at this point in the exchange Chomsky is writing to Harris as if he were guilty of dishonesty, unscholarly conduct, and collusion in covering up the crimes of the American government.

But which is it? Is Harris being dishonest when he says Chomsky is claiming moral equivalence? Or is he being dishonest when he fails to cite an earlier source arguing that in fact what the U.S. did was morally worse? The more important question, however, is why does Chomsky assume Harris is being dishonest, especially in light of how complicated his position is? Here’s what Chomsky writes in response to Harris pressing him to answer directly the question about moral equivalence:

Clinton bombed al-Shifa in reaction to the Embassy bombings, having discovered no credible evidence in the brief interim of course, and knowing full well that there would be enormous casualties. Apologists may appeal to undetectable humanitarian intentions, but the fact is that the bombing was taken in exactly the way I described in the earlier publication which dealt the question of intentions in this case, the question that you claimed falsely that I ignored: to repeat, it just didn’t matter if lots of people are killed in a poor African country, just as we don’t care if we kill ants when we walk down the street. On moral grounds, that is arguably even worse than murder, which at least recognizes that the victim is human. That is exactly the situation.

Most of the rest of the exchange consists of Harris trying to figure out Chomsky’s views on the role of intention in moral judgment, and Chomsky accusing Harris of dishonesty and evasion for not acknowledging and exploring the implications of the U.S.’s culpability in the al-Shifa atrocity. When Harris tries to explain his view on the bombing by describing a hypothetical scenario in which one group stages an attack with the intention of killing as many people as possible, comparing it to another scenario in which a second group stages an attack with the intention of preventing another, larger attack, killing as few people as possible in the process, Chomsky will have none it. He insists Harris’s descriptions are “so ludicrous as to be embarrassing,” because they’re nothing like what actually happened. We know Chomsky is an intelligent enough man to understand perfectly well how a thought experiment works. So we’re left asking, what accounts for his mindless pounding on the drum of the U.S.’s greater culpability? And, again, why is he so convinced Harris is carrying on in bad faith?

What seems to be going on here is that Chomsky, a long-time critic of American foreign policy, actually began with the conclusion he sought to arrive at. After arguing for decades that the U.S. was the ultimate bad guy in the geopolitical sphere, his first impulse after the attacks of 9/11 was to salvage his efforts at casting the U.S. as the true villain. Toward that end, he lighted on al-Shifa as the ideal crime to offset any claim to innocent victimhood. He’s actually been making this case for quite some time, and Harris is by no means the first to insist that the intentions behind the two attacks should make us judge them very differently. Either Chomsky felt he knew enough about Harris to treat him like a villain himself, or he has simply learned to bully and level accusations against anyone pursuing a line of questions that will expose the weakness of his idea—he likens Harris’s arguments at one point to “apologetics for atrocities”—a tactic he keeps getting away with because he has a large following of liberal academics who accept his moral authority.

Harris saw clear to the end-game of his debate with Chomsky, and it’s quite possible Chomsky in some murky way did as well. The reason he was so sneeringly dismissive of Harris’s attempts to bring the discussion around to intentions, the reason he kept harping on how evil America had been in bombing al-Shifa, is that by focusing on this one particular crime he was avoiding the larger issue of competing ideologies. Chomsky’s account of the bombing is not as certain as he makes out, to say the least. An earlier claim he made about a Human Rights Watch report on the death toll, for instance, turned out to be completely fictitious. But even if the administration really was lying about its motives, it’s noteworthy that a lie was necessary. When Bin Laden announced his goals, he did so loudly and proudly.

Chomsky’s one defense of his discounting of the attackers’ intentions (yes, he defends it, even though he accused Harris of being dishonest for pointing it out) is that everyone claims to have good intentions, so intentions simply don’t matter. This is shockingly facile coming from such a renowned intellectual—it would be shockingly facile coming from anyone. Of course Harris isn’t arguing that we should take someone’s own word for whether their intentions are good or bad. What Harris is arguing is that we should examine someone’s intentions in detail and make our own judgment about them. Al Qaeda’s plan to maximize terror by maximizing the death count of their attacks can only be seen as a good intention in the context of the group’s extreme religious ideology. That’s precisely why we should be discussing and criticizing that ideology, criticism which should extend to the more mainstream versions of Islam it grew out of.

Taking a step back from the particulars, we see that Chomsky believes the U.S. is guilty of far more and far graver acts of terror than any of the groups or nations officially designated as terrorist sponsors, and he seems unwilling to even begin a conversation with anyone who doesn’t accept this premise. Had he made some iron-clad case that the U.S. really did treat the pharmaceutical plant, and the thousands of lives that depended on its products, as pawns in some amoral game of geopolitical chess, he could have simply directed Harris to the proper source, or he could have reiterated key elements of that case. Regardless of what really happened with al-Shifa, we know full well what Al Qaeda’s intentions were, and Chomsky could have easily indulged Harris in discussing hypotheticals had he not feared that doing so would force him to undermine his own case. Is Harris an apologist for American imperialism? Here’s a quote from the section of his book discussing Chomsky's ideas:

We have surely done some terrible things in the past. Undoubtedly, we are poised to do terrible things in the future. Nothing I have written in this book should be construed as a denial of these facts, or as defense of state practices that are manifestly abhorrent. There may be much that Western powers, and the United States in particular, should pay reparations for. And our failure to acknowledge our misdeeds over the years has undermined our credibility in the international community. We can concede all of this, and even share Chomsky’s acute sense of outrage, while recognizing that his analysis of our current situation in the world is a masterpiece of moral blindness.

To be fair, lines like this last one are inflammatory, so it was understandable that Chomsky was miffed, up to a point. But Harris is right to point to his moral blindness, the same blindness that makes Aslan, Affleck, and Greenwald unable to see that the specific nature of beliefs and doctrines and governing principles actually matters. If we believe it’s evil to subjugate women, abuse homosexuals, and murder freethinkers, the fact that our country does lots of horrible things shouldn’t stop us from speaking out against these practices to people of every skin color, in every culture, on every part of the globe.

Sam Harris is no passive target in all of this. In a debate, he gives as good or better than he gets, and he has a penchant for finding the most provocative way to phrase his points—like calling Islam “the motherlode of bad ideas.” He doesn’t hesitate to call people out for misrepresenting his views and defaming him as a person, but I’ve yet to see him try to win an argument by going after the person making it. And I’ve never seen him try to sabotage an intellectual dispute with a cheap performance of moral outrage, or discredit opponents by fixing them with labels they don't deserve. Reading his writings and seeing him lecture or debate, you get the sense that he genuinely wants to test the strength of ideas against each other and see what new insight such exchanges may bring. That’s why it’s frustrating to see these discussions again and again go off the rails because his opponent feels justified in dismissing and condemning him based on inaccurate portrayals, from an overweening and unaccountable sense of self-righteousness.

Ironically, honoring the type of limits to calls for greater social justice that Aslan and Chomsky take as sacrosanct—where the West forebears to condescend to the rest—serves more than anything else to bolster the sense of division and otherness that makes many in the U.S. care so little about things like what happened in al-Shifa. As technology pushes on the transformation of our far-flung societies and diverse cultures into a global community, we ought naturally to start seeing people from Northern Africa and the Middle East—and anywhere else—not as scary and exotic ciphers, but as fellow citizens of the world, as neighbors even. This same feeling of connection that makes us all see each other as more human, more worthy of each other’s compassion and protection, simultaneously opens us up to each other’s criticisms and moral judgments. Chomsky is right that we Americans are far too complacent about our country’s many crimes. But opening the discussion up to our own crimes opens it likewise to other crimes that cannot be tolerated anywhere on the globe, regardless of the culture, regardless of any history of oppression, and regardless too of any sanction delivered from the diverse landscape of supposedly sacred realms.

Other popular posts like this:

THE SOUL OF THE SKEPTIC: WHAT PRECISELY IS SAM HARRIS WAKING UP FROM?

MEDIEVAL VS ENLIGHTENED: SORRY, MEDIEVALISTS, DAN SAVAGE WAS RIGHT

Capuchin-22: A Review of “The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism among the Primates” by Frans De Waal

THE SELF-RIGHTEOUSNESS INSTINCT: STEVEN PINKER ON THE BETTER ANGELS OF MODERNITY AND THE EVILS OF MORALITY

Medieval vs Enlightened: Sorry, Medievalists, Dan Savage Was Right

The medievalist letter writer claims that being “part of the center” is what makes living in the enlightened West preferable to living in the 12th century. But there’s simply no way whoever wrote the letter actually believes this. If you happen to be poor, female, a racial or religious minority, a homosexual, or a member of any other marginalized group, you’d be far more loath to return to the Middle Ages than those of us comfortably ensconced in this notional center, just as you’d be loath to relocate to any society not governed by Enlightenment principles today.

A letter from an anonymous scholar of the medieval period to the sex columnist Dan Savage has been making the rounds of social media lately. Responding to a letter from a young woman asking how she should handle sex for the first time with her Muslim boyfriend, who happened to be a virgin, Savage wrote, “If he’s still struggling with the sex-negative, woman-phobic zap that his upbringing (and a medieval version of his faith) put on his head, he needs to work through that crap before he gets naked with you.” The anonymous writer bristles in bold lettering at Savage’s terminology: “I’m a medievalist, and this is one of the things about our current discourse on religion that drives me nuts. Contemporary radical Christianity, Judaism, and Islam are all terrible, but none of them are medieval, especially in terms of sexuality.” Oddly, however, the letter, published under the title, “A Medievalist Schools Dan on Medieval Attitudes toward Sex,” isn’t really as much about correcting popular misconceptions about sex in the Middle Ages as it is about promoting a currently fashionable but highly dubious way of understanding radical religion in the various manifestations we see today.

While the medievalist’s overall argument is based far more on ideology than actual evidence, the letter does make one important and valid point. As citizens of a technologically advanced secular democracy, it’s tempting for us to judge other cultures by the standards of our own. Just as each of us expects every young person we encounter to follow a path to maturity roughly identical to the one we’ve taken ourselves, people in advanced civilizations tend to think of less developed societies as occupying one or another of the stages that brought us to our own current level of progress. This not only inspires a condescending attitude toward other cultures; it also often leads to an overly simplified understanding of our own culture’s history. The letter to Savage explains:

I’m not saying that the Middle Ages was a great period of freedom (sexual or otherwise), but the sexual culture of 12th-century France, Iraq, Jerusalem, or Minsk did not involve the degree of self-loathing brought about by modern approaches to sexuality. Modern sexual purity has become a marker of faith, which it wasn’t in the Middle Ages. (For instance, the Bishop of Winchester ran the brothels in South London—for real, it was a primary and publicly acknowledged source of his revenue—and one particularly powerful Bishop of Winchester was both the product of adultery and the father of a bastard, which didn’t stop him from being a cardinal and papal legate.) And faith, especially in modern radical religion, is a marker of social identity in a way it rarely was in the Middle Ages.

If we imagine the past as a bad dream of sexual repression from which our civilization has only recently awoken, historical tidbits about the prevalence and public acceptance of prostitution may come as a surprise. But do these revelations really undermine any characterization of the period as marked by religious suppression of sexual freedom?

Obviously, the letter writer’s understanding of the Middle Ages is more nuanced than most of ours, but the argument reduces to pointing out a couple of random details to distract us from the bigger picture. The passage quoted above begins with an acknowledgement that the Middle Ages was not a time of sexual freedom, and isn’t it primarily that lack of freedom that Savage was referring to when he used the term medieval? The point about self-loathing is purely speculative if taken to apply to the devout generally, and simply wrong with regard to ascetics who wore hairshirts, flagellated themselves, or practiced other forms of mortification of the flesh. In addition, we must wonder how much those prostitutes enjoyed the status conferred on them by the society that was supposedly so accepting of their profession; we must also wonder if this medievalist is aware of what medieval Islamic scholars like Imam Malik (711-795) and Imam Shafi (767-820) wrote about homosexuality. The letter writer is on shaky ground yet again with regard to the claim that sexual purity wasn’t a marker of faith (though it’s hard to know precisely what the phrase even means). There were all kinds of strange prohibitions in Christendom against sex on certain days of the week, certain times of the year, and in any position outside of missionary. Anyone watching the BBC’s adaptation of Wolf Hall knows how much virginity was prized in women—as King Henry VIII could only be wed to a woman who’d never had sex with another man. And there’s obviously an Islamic tradition of favoring virgins, or else why would so many of them be promised to martyrs? Finally, of course faith wasn’t a marker of social identity—nearly everyone in every community was of the same faith. If you decided to take up another set of beliefs, chances are you’d have been burned as a heretic or beheaded as an apostate.

The letter writer is eager to make the point that the sexual mores espoused by modern religious radicals are not strictly identical to the ones people lived according to in the Middle Ages. Of course, the varieties of religion in any one time aren’t ever identical to those in another, or even to others in the same era. Does anyone really believe otherwise? The important question is whether there’s enough similarity between modern religious beliefs on the one hand and medieval religious beliefs on the other for the use of the term to be apposite. And the answer is a definitive yes. So what is the medievalist’s goal in writing to correct Savage? The letter goes on,

The Middle Eastern boyfriend wasn’t taught a medieval version of his faith, and radical religion in the West isn’t a retreat into the past—it is a very modern way of conceiving identity. Even something like ISIS is really just interested in the medieval borders of their caliphate; their ideology developed out of 18th- and 19th-century anticolonial sentiment. The reason why this matters (beyond medievalists just being like, OMG no one gets us) is that the common response in the West to religious radicalism is to urge enlightenment, and to believe that enlightenment is a progressive narrative that is ever more inclusive. But these religions are responses to enlightenment, in fact often to The Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, is popularly thought to have been the end of the Middle or so-called Dark Ages. The story goes that the medieval period was a time of Catholic oppression, feudal inequality, stunted innovation, and rampant violence. Then some brilliant philosophers woke the West up to the power of reason, science, and democracy, thus marking the dawn of the modern world. Historians and academics of various stripes like to sneer at this story of straightforward scientific and moral progress. It’s too simplistic. It ignores countless atrocities perpetrated by those supposedly enlightened societies. And it undergirds an ugly contemptuousness toward less advanced cultures. But is the story of the Enlightenment completely wrong?

The medievalist letter writer makes no bones about the source of his ideas, writing in a parenthetical, “Michel Foucault does a great job of talking about these developments, and modern sexuality, including homosexual and heterosexual identity, as well—and I’m stealing and watering down his thoughts here.” Foucault, though he eschewed the label, is a leading figure in poststructuralist and postmodern schools of thought. His abiding interest throughout his career was with the underlying dynamics of social power as they manifested themselves in the construction of knowledge. He was one of those French philosophers who don’t believe in things like objective truth, human nature, or historical progress of any kind.

Foucault and the scores of scholars inspired by his work take it as their mission to expose all the hidden justifications for oppression in our culture’s various media for disseminating information. Why they would bother taking on this mission in the first place, though, is a mystery, beginning as they do from the premise that any notion of moral progress can only be yet another manifestation of one group’s power over another. If you don’t believe in social justice, why pursue it? If you don’t believe in truth, why seek it out? And what are Foucault’s ideas about the relationship between knowledge and power but theories of human nature? Despite this fundamental incoherence, many postmodern academics today zealously pounce on any opportunity to chastise scientists, artists, and other academics for alleged undercurrents in their work of sexism, racism, homophobia, Islamophobia, or some other oppressive ideology. Few sectors of academia remain untouched by this tradition, and its influence leads legions of intellectuals to unselfconsciously substitute sanctimony for real scholarship.

So how do Foucault and the medievalist letter writer view the Enlightenment? The letter refers vaguely to “concepts of mass culture and population.” Already, it seems we’re getting far afield of how most historians and philosophers characterize the Enlightenment, not to mention how most Enlightenment figures themselves described their objectives. The letter continues,

Its narrative depends upon centralized control: It gave us the modern army, the modern prison, the mental asylum, genocide, and totalitarianism as well as modern science and democracy. Again, I’m not saying that I’d prefer to live in the 12th century (I wouldn’t), but that’s because I can imagine myself as part of that center. Educated, well-off Westerners generally assume that they are part of the center, that they can affect the government and contribute to the progress of enlightenment. This means that their identity is invested in the social form of modernity.

It’s true that the terms Enlightenment and Dark Ages were first used by Western scholars in the nineteenth century as an exercise in self-congratulation, and it’s also true that any moral progress that was made over the period occurred alongside untold atrocities. But neither of these complications to the oversimplified version of the narrative establishes in any way that the Enlightenment never really occurred—as the letter writer’s repeated assurances that it’s preferable to be alive today ought to make clear. What’s also clear is that this medievalist is deliberately conflating enlightenment with modernity, so that all the tragedies and outrages of the modern world can be laid at the feet of enlightenment thinking. How else could he describe the enlightenment as being simultaneously about both totalitarianism and democracy? But not everything that happened after the Enlightenment was necessarily caused by it, and nor should every social institution that arose from the late 19th to the early 20th century be seen as representative of enlightenment thinking.

The medievalist letter writer claims that being “part of the center” is what makes living in the enlightened West preferable to living in the 12th century. But there’s simply no way whoever wrote the letter actually believes this. If you happen to be poor, female, a racial or religious minority, a homosexual, or a member of any other marginalized group, you’d be far more loath to return to the Middle Ages than those of us comfortably ensconced in this notional center, just as you’d be loath to relocate to any society not governed by Enlightenment principles today.

The medievalist insists that groups like ISIS follow an ideology that dates to the 18th and 19th centuries and arose in response to colonialism, implying that Islamic extremism would be just another consequence of the inherently oppressive nature of the West and its supposedly enlightened ideas. “Radical religion,” from this Foucauldian perspective, offers a social identity to those excluded (or who feel excluded) from the dominant system of Western enlightenment capitalism. It is a modern response to a modern problem, and by making it seem like some medieval holdover, we cover up the way in which our own social power produces the conditions for this kind of identity, thus making violence appear to be the only response for these recalcitrant “holdouts.”

This is the position of scholars and journalists like Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald as well. It’s emblematic of the same postmodern ideology that forces on us the conclusion that if chimpanzees are violent to one another, it must be the result of contact with primatologists and other humans; if indigenous people in traditionalist cultures go to war with their neighbors, it must be owing to contact with missionaries and anthropologists; and if radical Islamists are killing their moderate co-religionists, kidnapping women, or throwing homosexuals from rooftops, well, it can only be the fault of Western colonialism. Never mind that these things are prescribed by holy texts dating from—you guessed it—the Middle Ages. The West, to postmodernists, is the source of all evil, because the West has all the power.

Directionality in Societal Development

But the letter writer’s fear that thinking of radical religion as a historical holdover will inevitably lead us to conclude military action is the only solution is based on an obvious non sequitur. There’s simply no reason someone who sees religious radicalism as medieval must advocate further violence to stamp it out. And that brings up another vital question: what solution do the postmodernists propose for things like religious violence in the Middle East and Africa? They seem to think that if they can only convince enough people that Western culture is inherently sexist, racist, violent, and so on—basically a gargantuan engine of oppression—then every geopolitical problem will take care of itself somehow.

If it’s absurd to believe that everything that comes from the West is good and pure and true just because it comes from the West, it’s just as absurd to believe that everything that comes from the West is evil and tainted and false for the same reason. Had the medievalist spent some time reading the webpage on the Enlightenment so helpfully hyperlinked to in the letter, whoever it is may have realized how off-the-mark Foucault’s formulation was. The letter writer gets it exactly wrong in the part about mass culture and population, since the movement is actually associated with individualism, including individual rights. But what best distinguishes enlightenment thinking from medieval thinking, in any region or era, is the conviction that knowledge, justice, and better lives for everyone in the society are achievable through the application of reason, science, and skepticism, while medieval cultures rely instead on faith, scriptural or hierarchical authority, and tradition. The two central symbols of the Enlightenment are Galileo declaring that the church was wrong to dismiss the idea of a heliocentric cosmos and the Founding Fathers appending the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution. You can argue that it’s only owing to a history of colonialism that Western democracies today enjoy the highest standard of living among all the nations of the globe. But even the medievalist letter writer attests to how much better it is to live in enlightened countries today than in the same countries in the Middle Ages.

The postmodernism of Foucault and his kindred academics is not now, and has not ever been, compelling on intellectual grounds, which leaves open the question of why so many scholars have turned against the humanist and Enlightenment ideals that once gave them their raison d’être. I can’t help suspecting that the appeal of postmodernism stems from certain religious qualities of the worldview, qualities that ironically make it resemble certain aspects of medieval thought: the bowing to the authority of celebrity scholars (mostly white males), the cloistered obsession with esoteric texts, rituals of expiation and self-abasement, and competitive finger-wagging. There’s even a core belief in something very like original sin; only in this case it consists of being born into the ranks of a privileged group whose past members were guilty of some unspeakable crime. Postmodern identity politics seems to appeal most strongly to whites with an overpowering desire for acceptance by those less fortunate, as if they were looking for some kind of forgiveness or redemption only the oppressed have the power to grant. That’s why these academics are so quick to be persuaded they should never speak up unless it’s on behalf of some marginalized group, as if good intentions were proof against absurdity. As safe and accommodating and well-intentioned as this stance sounds, though, in practice it amounts to little more than moral and intellectual cowardice.

Life really has gotten much better since the Enlightenment, and it really does continue to get better for an increasing number of formerly oppressed groups of people today. All this progress has been made, and continues being made, precisely because there are facts and ideas—scientific theories, human rights, justice, and equality—that transcend the social conditions surrounding their origins. Accepting this reality doesn’t in any way mean seeing violence as the only option for combatting religious extremism, despite many academics’ insistence to the contrary. Nor does it mean abandoning the cause of political, cultural, and religious pluralism. But, if we continue disavowing the very ideals that have driven this progress, however fitfully and haltingly it has occurred, if we continue denying that it can even be said to have occurred at all, then what hope can we possibly have of pushing it even further along in the future?

Also read:

THE IDIOCY OF OUTRAGE: SAM HARRIS'S RUN-INS WITH BEN AFFLECK AND NOAM CHOMSKY

And:

And:

And:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

On ISIS's explicit avowal of adherence to medieval texts: “What ISIS Really Wants" by Graeme Wood of the Atlantic

The Soul of the Skeptic: What Precisely Is Sam Harris Waking Up from?

In my first foray into Sam Harris’s work, I struggle with some of the concepts he holds up as keys to a more contented, more spiritual life. Along the way, though, I find myself captivated by the details of Harris’s own spiritual journey, and I’m left wondering if there just may be more to this meditation stuff than I’m able to initially wrap my mind around.

Sam Harris believes that we can derive many of the benefits people cite as reasons for subscribing to one religion or another from non-religious practices and modes of thinking, ones that don’t invoke bizarre scriptures replete with supernatural absurdities. In The Moral Landscape,for instance, he attempted to show that we don’t need a divine arbiter to settle our ethical and political disputes because reason alone should suffice. Now, with Waking Up, Harris is taking on an issue that many defenders of Christianity, or religion more generally, have long insisted he is completely oblivious to. By focusing on the truth or verifiability of religious propositions, Harris’s critics charge, he misses the more important point: religion isn’t fundamentally about the beliefs themselves so much as the effects those beliefs have on a community, including the psychological impact on individuals of collective enactments of the associated rituals—feelings of connectedness, higher purpose, and loving concern for all one’s neighbors.

Harris likes to point out that his scholarly critics simply have a hard time appreciating just how fundamentalist most religious believers really are, and so they turn a blind eye toward the myriad atrocities religion sanctions, or even calls for explicitly. There’s a view currently fashionable among the more politically correct scientists and academics that makes criticizing religious beliefs seem peevish, even misanthropic, because religion is merely something people do, like reading stories or playing games, to imbue their lives with texture and meaning, or to heighten their sense of belonging to a community. According to this view, the particular religion in question—Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Christianity—isn’t as important as the people who subscribe to it, nor do any specific tenets of a given faith have any consequence. That’s why Harris so frequently comes under fire—and is even accused of bigotry—for suggesting things like that the passages in the Koran calling for violence actually matter and that Islam is much more likely to inspire violence because of them.

We can forgive Harris his impatience with this line of reasoning, which leads his critics to insist that violence is in every case politically and never religiously motivated. This argument can only be stated with varying levels of rancor, never empirically supported, and is hence dismissible as a mere article of faith in its own right, one that can’t survive any encounter with the reality of religious violence. Harris knows how important a role politics plays and that it’s often only the fundamentalist subset of the population of believers who are dangerous. But, as he points out, “Fundamentalism is only a problem when the fundamentals are a problem” (2:30:09). It’s only by the lights of postmodern identity politics that an observation this banal could strike so many as so outrageous.

But what will undoubtedly come as a disappointment to Harris’s more ardently anti-religious readers, and as a surprise to fault-seeking religious apologists, is that from the premise that not all religions are equally destructive and equally absurd follows the conclusion that some religious ideas or practices may actually be beneficial or point the way toward valid truths. Harris has discussed his experiences with spiritual retreats and various forms of meditation in past works, but now with Waking Up he goes so far as to advocate certain of the ancient contemplative practices he’s experimented with. Has he abandoned his scientific skepticism? Not by any means; near the end of the book, he writes, “As a general matter, I believe we should be very slow to draw conclusions about the nature of the cosmos on the basis of inner experiences—no matter how profound they seem” (192). What he’s doing here, and with the book as a whole, is underscoring the distinction between religious belief on the one hand and religious experience on the other.

Acknowledging that some practices which are nominally religious can be of real value, Harris goes on to argue that we need not accept absurd religious doctrines to fully appreciate them. And this is where the subtitle of his book, A Guide to Spirituality without Religion, comes from. As paradoxical as this concept may seem to people of faith, Harris cites a survey finding that 20% of Americans describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious” (6). And he argues that separating the two terms isn’t just acceptable; it’s logically necessary.

Spirituality must be distinguished from religion—because people of every faith, and of none, have the same sorts of spiritual experiences. While these states of mind are usually interpreted through the lens of one or another religious doctrine, we know this is a mistake. Nothing that a Christian, a Muslim, and a Hindu can experience—self-transcending love, ecstasy, bliss, inner light—constitutes evidence in support of their traditional beliefs, because their beliefs are logically incompatible with one another. A deeper principle must be at work. (9)

People of faith frequently respond to the criticism that their beliefs fly in the face of logic and evidence by claiming they simply know God is real because they have experiences that can only be attributed to a divine presence. Any failure on the part of skeptics to acknowledge the lived reality of such experiences makes their arguments all the more easily dismissible as overly literal or pedantic, and it makes the skeptics themselves come across as closed-minded and out-of-touch.

On the other hand, Harris’s suggestion of a “deeper principle” underlying religious experiences smacks of New Age thinking at its most wooly. For one thing, church authorities often condemn, excommunicate, or execute congregants with mystical leanings for their heresy. (Harris cites a few examples.) But the deeper principle Harris is referring to isn’t an otherworldly one. And he’s perfectly aware of the unfortunate connotations the words he uses often carry:

I share the concern, expressed by many atheists, that the terms spiritual and mystical are often used to make claims not merely about the quality of certain experiences but about reality at large. Far too often, these words are invoked in support of religious beliefs that are morally and intellectually grotesque. Consequently, many of my fellow atheists consider all talk of spirituality to be a sign of mental illness, conscious imposture, or self-deception. This is a problem, because millions of people have had experiences for which spiritual and mystical seem the only terms available. (11)

You can’t expect people to be convinced their religious beliefs are invalid when your case rests on a denial of something as perfectly real to them as their own experiences. And it’s difficult to make the case that these experiences must be separated from the religious claims they’re usually tied to while refusing to apply the most familiar labels to them, because that comes awfully close to denying their legitimacy.

*****

Throughout Waking Up, Harris focuses on one spiritual practice in particular, a variety of meditation that seeks to separate consciousness from any sense of self, and he argues that the insights one can glean from experiencing this rift are both personally beneficial and neuroscientifically sound. Certain Hindu and Buddhist traditions hold that the self is an illusion, a trick of the mind, and our modern scientific understanding of the mind, Harris argues, corroborates this view. By default, most of us think of the connection between our minds and our bodies dualistically; we believe we have a spirit, a soul, or some other immaterial essence that occupies and commands our physical bodies. Even those of us who profess not to believe in any such thing as a soul have a hard time avoiding a conception of the self as a unified center of consciousness, a homunculus sitting at the controls. Accordingly, we attach ourselves to our own thoughts and perceptions—we identify with them. Since it seems we’re programmed to agonize over past mistakes and worry about impending catastrophes, we can’t help feeling the full brunt of a constant barrage of negative thoughts. Most of us recognize the sentiment Harris expresses in writing that “It seems to me that I spend much of my life in a neurotic trance” (11). And this is precisely the trance we need to wake up from.

To end the spiraling chain reaction of negative thoughts and foul feelings, we must detach ourselves from our thinking, and to do this, Harris suggests, we must recognize that there is no us doing the thinking. The “I” in the conventional phrasing “I think” or “I feel” is nowhere to be found. Is it in our brains? Which part? Harris describes the work of the Nobel laureate neuroscientist Roger Sperry, who in the 1950s did a series a fascinating experiments with split-brain patients, so called because the corpus callosum, the bundle of fibers connecting the two hemispheres of their brains, had been surgically severed to reduce the severity of epileptic seizures. Sperry found that he could present instructions to the patients’ left visual fields—which would only be perceived by the right hemisphere—and induce responses that the patients themselves couldn’t explain, because language resides predominantly in the left hemisphere. When asked to justify their behavior, though, the split-brain patients gave no indication that they had no idea why they were doing what they’d been instructed to do. Instead, they confabulated answers. For instance, if the right hemisphere is instructed to pick up an egg from among an assortment of objects on a table, the left hemisphere may explain the choice by saying something like, “Oh, I picked it because I had eggs for breakfast yesterday.”

As weird as this type of confabulation may seem, it has still weirder implications. At any given moment, it’s easy enough for us to form intentions and execute plans for behavior. But where do those intentions really come from? And how can we be sure our behaviors reflect the intentions we believe they reflect? We are only ever aware of a tiny fraction of our minds’ operations, so it would be all too easy for us to conclude we are the ones in charge of everything we do even though it’s really someone—or something else behind the scenes pulling the strings. The reason split-brain patients so naturally confabulate about their motives is that the language centers of our brains probably do it all the time, even when our corpus callosa are intact. We are only ever dimly aware of our true motivations, and likely completely in the dark about them as often as not. Whenever we attempt to explain ourselves, we’re really just trying to make up a plausible story that incorporates all the given details, one that makes sense both to us and to anyone listening.

If you’re still not convinced that the self is an illusion, try to come up with a valid justification for locating the self in either the left or the right hemisphere of split-brain patients. You may be tempted to attribute consciousness, and hence selfhood, to the hemisphere with the capacity for language. But you can see for yourself how easy it is to direct your attention away from words and fill your consciousness solely with images or wordless sounds. Some people actually rely on their right hemispheres for much of their linguistic processing, and after split-brain surgery these people can speak for the right hemisphere with things like cards that have written words on them. We’re forced to conclude that both sides of the split brain are conscious. And, since the corpus callosum channels a limited amount of information back and forth in the brain, we probably all have at least two independent centers of consciousness in our minds, even those of us whose hemispheres communicate.

What this means is that just because your actions and intentions seem to align, you still can’t be sure there isn’t another conscious mind housed in your brain who is also assured its own actions and intentions are aligned. There have even been cases where the two sides of a split-brain patient’s mind have expressed conflicting beliefs and desires. For some, phenomena like these sound the death knell for any dualistic religious belief. Harris writes,

Consider what this says about the dogma—widely held under Christianity and Islam—that a person’s salvation depends upon her believing the right doctrine about God. If a split-brain patient’s left hemisphere accepts the divinity of Jesus, but the right doesn’t, are we to imagine that she now harbors two immortal souls, one destined for the company of angels and the other for an eternity of hellfire? (67-8)

Indeed, the soul, the immaterial inhabitant of the body, can be divided more than once. Harris makes this point using a thought experiment originally devised by philosopher Derek Parfit. Imagine you are teleported Star Trek-style to Mars. The teleporter creates a replica of your body, including your brain and its contents, faithful all the way down to the orientation of the atoms. So everything goes black here on Earth, and then you wake up on Mars exactly as you left. But now imagine something went wrong on Earth and the original you wasn’t destroyed before the replica was created. In that case, there would be two of you left whole and alive. Which one is the real you? There’s no good basis for settling the question one way or the other.

Harris uses the split-brain experiments and Parfit’s thought experiment to establish the main insight that lies at the core of the spiritual practices he goes on to describe: that the self, as we are programmed to think of and experience it, doesn’t really exist. Of course, this is only true in a limited sense. In many contexts, it’s still perfectly legitimate to speak of the self. As Harris explains,

The self that does not survive scrutiny is the subject of experience in each present moment—the feeling of being a thinker of thoughts inside one’s head, the sense of being an owner or inhabitant of a physical body, which this false self seems to appropriate as a kind of vehicle. Even if you don’t believe such a homunculus exists—perhaps because you believe, on the basis of science, that you are identical to your body and brain rather than a ghostly resident therein—you almost certainly feel like an internal self in almost every waking moment. And yet, however one looks for it, this self is nowhere to be found. It cannot be seen amid the particulars of experience, and it cannot be seen when experience itself is viewed as a totality. However, its absence can be found—and when it is, the feeling of being a self disappears. (92)

The implication is that even if you come to believe as a matter of fact that the self is an illusion you nevertheless continue to experience that illusion. It’s only under certain circumstances, or as a result of engaging in certain practices, that you’ll be able to experience consciousness in the absence of self.

****

Harris briefly discusses avenues apart from meditation that move us toward what he calls “self-transcendence”: we often lose ourselves in our work, or in a good book or movie; we may feel a diminishing of self before the immensities of nature and the universe, or as part of a drug-induced hallucination; or it could be attendance at a musical performance where you’re just one tiny part of a vast pulsing crowd of exuberant fans. It could be during intense sex. Or you may of course also experience some fading away of your individuality through participation in religious ceremonies. But Harris’s sights are set on one specific method for achieving self-transcendence. As he writes in his introduction,

This book is by turns a seeker’s memoir, an introduction to the brain, a manual of contemplative instruction, and a philosophical unraveling of what most people consider to be the center of their inner lives: the feeling of self we call “I.” I have not set out to describe all the traditional approaches to spirituality and to weigh their strengths and weaknesses. Rather, my goal is to pluck the diamond from the dunghill of esoteric religion. There is a diamond there, and I have devoted a fair amount of my life to contemplating it, but getting it in hand requires that we remain true to the deepest principles of scientific skepticism and make no obeisance to tradition. (10)

This is music to the ears of many skeptics who have long suspected that there may actually be something to meditative techniques but are overcome with fits of eye-rolling every time they try to investigate the topic. If someone with skeptical bona fides as impressive as Harris’s has taken the time to wade through all the nonsense to see if there are any worthwhile takeaways, then I imagine I’m far from alone in being eager to find out what he’s discovered.

So how does one achieve a state of consciousness divorced from any sense of self? And how does this experience help us escape the neurotic trance most of us are locked in? Harris describes some of the basic principles of Advaita, a Hindu practice, and Dzogchen, a Tibetan Buddhist one. According to Advaita, one can achieve “cessation”—an end to thinking, and hence to the self—at any stage of practice. But Dzogchen practitioners insist it comes only after much intense practice. In one of several inset passages with direct instructions to readers, Harris invites us to experiment with the Dzogchen technique of imagining a moment in our lives when we felt positive emotions, like the last time we accomplished something we’re proud of. After concentrating on the thoughts and feelings for some time, we are then encouraged to think of a time when we felt something negative, like embarrassment or fear. The goal here is to be aware of the ideas and feelings as they come into being. “In the teachings of Dzogchen,” Harris writes, “it is often said that thoughts and emotions arise in consciousness the way that images appear on the surface of the mirror.” Most of the time, though, we are tricked into mistaking the mirror for what’s reflected in it.

In subjective terms, you are consciousness itself—you are not the next, evanescent image or string of words that appears in your mind. Not seeing it arise, however, the next thought will seem to become what you are. (139)

This is what Harris means when he speaks of separating your consciousness from your thoughts. And he believes it’s a state of mind you can achieve with sufficient practice calling forth and observing different thoughts and emotions, until eventually you experience—for moments at a time—a feeling of transcending the self, which entails a ceasing of thought, a type of formless and empty awareness that has us sensing a pleasant unburdening of the weight of our identities.

Harris also describes a more expeditious route to selflessness, one discovered by a British Architect named Douglas Harding, who went on to be renowned among New Agers for his insight. His technique, which was first inspired by a drawing made by physicist Ernst Mach that was a literal rendition of his first-person viewpoint, including the side of his nose and the ridge of his eyebrow, consists simply of trying to imagine you have no head. Harris quotes at length from Harding’s description of what happened when he originally succeeded:

What actually happened was something absurdly simply and unspectacular: I stopped thinking. A peculiar quiet, an odd kind of alert limpness or numbness, came over me. Reason and imagination and all mental chatter died down. For once, words really failed me. Past and future dropped away. I forgot who and what I was, my name, manhood, animal-hood, all that could be called mine. It was as if I had been born that instant, brand new, mindless, innocent of all memories. There existed only the Now, the present moment and what was clearly given it. (143)

Harris recommends a slight twist to this approach—one that involves looking out at the world and simply trying to reverse your perspective to look for your head. One way to do this is to imagine you’re talking to another person and then “let your attention travel in the direction of the other person’s gaze” (145). It’s not about trying to picture what you look like to another person; it’s about recognizing that your face is absent from the encounter—because obviously you can’t see it. “But looking for yourself in this way can precipitate a sudden change in perspective, of the sort Harding describes” (146). It’s a sort of out-of-body experience.

If you pull off the feat of seeing through the illusion of self, either through disciplined practice at observing the contents of your own consciousness or through shortcuts like imagining you have no head, you will experience a pronounced transformation. Even if for only a few moments, you will have reached enlightenment. As a reward for your efforts, you will enjoy a temporary cessation of the omnipresent hum of anxiety-inducing thoughts that you hardly even notice drowning out so much of the other elements of your consciousness. “There arose no questions,” Harding writes of his experiments in headlessness, “no reference beyond the experience itself, but only peace and a quiet joy, and the sensation of having dropped an intolerable burden” (143). Skeptics reading these descriptions will have to overcome the temptation to joke about practitioners without a thought in their head.

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam are all based on dualistic conceptions of the self, and the devout are enjoined to engage in ritual practices in service to God, an entirely separate being. The more non-dualistic philosophies of the East are much more amenable to attempts to reconcile them with science. Practices like meditation aren’t directed at any supernatural entity but are engaged in for their own sake, because they are somehow inherently rewarding. Unfortunately, this leads to a catch-22. Harris explains,

As we have seen, there are good reasons to believe that adopting a practice like meditation can lead to positive changes in one’s life. But the deepest goal of spirituality is freedom from the illusion of the self—and to seek such freedom, as though it were a future state to be attained through effort, is to reinforce the chains of one’s apparent bondage in each moment. (123)

This paradox seems at first like a good recommendation for the quicker routes to self-transcendence like Harding’s. But, according to Harris, “Harding confessed that many of his students recognized the state of ‘headlessness’ only to say, ‘So what?’” To Harris, the problem here is that the transformation was so easily achieved that its true value couldn’t be appreciated:

Unless a person has spent some time seeking self-transcendence dualistically, she is unlikely to recognize that the brief glimpse of selflessness is actually the answer to her search. Having then said, ‘So what?’ in the face of the highest teachings, there is nothing for her to do but persist in her confusion. (148)

We have to wonder, though, if maybe Harding’s underwhelmed students aren’t the ones who are confused. It’s entirely possible that Harris, who has devoted so much time and effort to his quest for enlightenment, is overvaluing the experience to assuage his own cognitive dissonance.

****

The penultimate chapter of Waking Up gives Harris’s more skeptical fans plenty to sink their teeth into, including a thorough takedown of neurosurgeon Eben Alexander’s so-called Proof of Heaven and several cases of supposedly enlightened gurus taking advantage of their followers by, among other exploits, sleeping with their wives. But Harris claims his own experiences with gurus have been almost entirely positive, and he goes as far as recommending that anyone hoping to achieve self-transcendence seek out the services of one.

This is where I began to have issues with the larger project behind Harris’s book. If meditation were a set of skills like those required to play tennis, it would seem more reasonable to claim that the guidance of an expert coach is necessary to develop them. But what is a meditation guru supposed to do if he (I presume they’re mostly male) has no way to measure, or even see, your performance? Harris suggests they can answer questions that arise during practice, but apart from basic instructions like the ones Harris himself provides it seems unlikely an expert could be of much help. If a guru has a useful technique, he shouldn’t need to be present in the room to share it. Harding passed his technique on to Harris through writing for instance. And if self-transcendence is as dramatic a transformation as it’s made out to be, you shouldn’t have any trouble recognizing it when you experience it.