READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

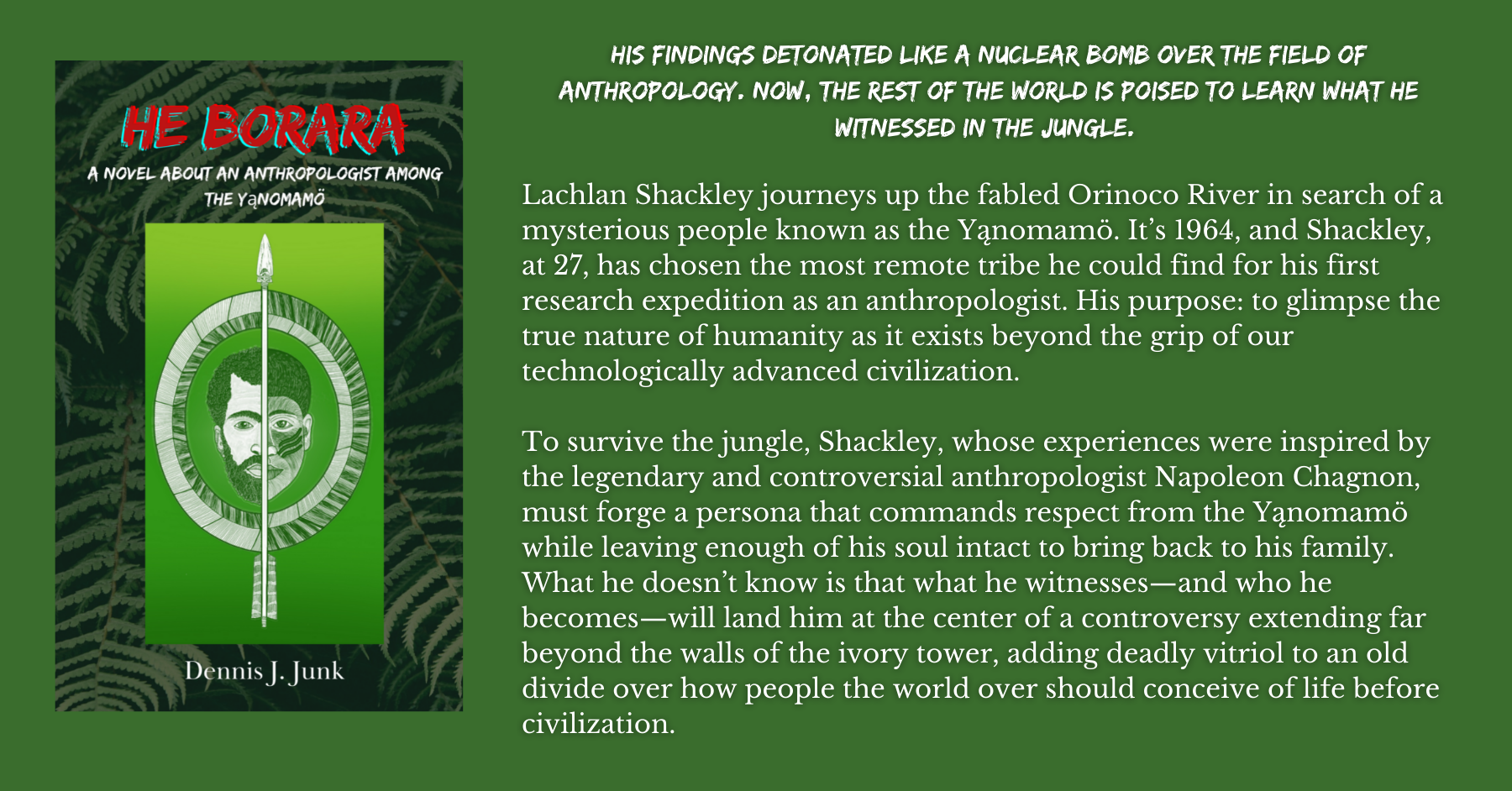

From the Blood of the Cannibal Moon: He Borara Part 3 Chapter 1

Origin myth of the Yanomamo. Sample chapter of “He Borara: a Novel about an Anthropologist among the Yąnomamö.”

The move into the mythic past encompasses a transition from existence to essence. When the events in these stories told by great shamans took place, the characters and places described in them had no beginnings and no ends. You must understand, if you want to appreciate the underlying truth of the stories, that the boundaries separating the mythic realm from the time-bound world are sometimes porous, but never more so than they were in the time of Moonblood. So there’s no contradiction when a shaman says, in a time before men, two men drew their bows and fired arrows at the moon.

These two brothers, Uhudima and Suhirima, were not men as we know them today, men like you and me. They were no badabö, which means “those who are now dead,” but also means “the original humans,” and they were part human, part animal, and part spirit. The moon, Peribo, likewise partook of multiple essences, and he nightly stole away with members of the no badabö village to press them between two pieces of cassava bread and devour them, until the two brothers decided Peribo must be stopped. As the moon retreated toward the horizon, Uhudima aimed his bow and loosed an arrow. He missed. Then he missed again. The Yąnomamö say Uhudima was sina—a lousy shot.

But his brother Suhirima was an excellent marksman. Even after Uhudima missed shot after shot, allowing Peribo to escape nearly all the way the horizon, Suhirima was able to take steady aim with his own bow and shoot an arrow that planted itself deep in Peribo’s belly. The wound disgorged great gouts of blood that fell to the earth as Peribo’s screams echoed across the sky. Wherever the blood landed sprang up a Yąnomamö—a true human being like the ones in these villages today. Something of the moon’s essence, his fury and bloodthirst, transferred to these newly born beings, making them waiteri, fearless and fiercely protective of their honor.

The first Yąnomamö no sooner sprang forth from the blood of the cannibal moon than they set about fighting and killing each other. They may have gone on to wipe themselves entirely out of existence, but in some parts of the hei kä misi, the layer of the cosmos we’re standing on now, the blood of the moon was diluted by water from streams and ponds and swamps. The Yąnomamö who arose from this washed blood were less warlike, fighting fiercely but not as frequently. The purest moon blood landed near the center of the hei kä misi, and even today you notice that the Yąnomamö in this area are far fiercer than those you encounter as you move toward the edges of the layer, a peripheral region where the ground is friable and crumbling.

Even the more peaceful Yąnomamö far from where the purest moon blood landed would have died out eventually because there were no women among them. But one day, the headman from one of the original villages was out with his men gathering vines for making hammocks and for lashing together support beams for their shabono. He was pulling a vine from the tree it clung to when he noticed an odd-looking fruit. Picking it from the tree and turning it in his hand, he saw that the fruit, which is called wabu, had a pair of eyes that were looking back at him.

The headman wondered aloud, “Is this what a woman looks like?” He satisfied his curiosity, examining the fruit closely for several long moments, but he knew there was still work to be done, so he tossed the wabu on the ground and went back to pulling vines from trees.

What he didn’t see was that upon hitting the ground the wabu transformed into a woman, like the ones we see today, only this one’s vagina was especially large and hairy, traits that fire Yąnomamö men’s lust. When the men finished pulling down their vines and began dragging the bundles back along the jungle trail to their shabono, this original woman succumbed to her mischievous streak. She followed behind the men, jumping behind trees whenever they turned back, which they did each time she ran up to the ends of the vines dragging behind them and stepped on them, causing the men to drop their entire bundle. They grew frustrated to the point of rage. Finally, when the men had nearly reached their shabono, the woman stepped on the end of a vine and remained standing there when the men turned around.

Seeing this creature with strange curves and with her great, hairy vagina in place of an up-tied penis, the men felt their frustration commingle with their lust, whipping them into a frenzy. They surrounded her and took turns copulating with her. Once they’d each taken a turn, they brought her back to their shabono, where the rest of the men of the village were likewise overcome with lust and likewise took turns copulating with her. The woman stayed in the shabono for many months until her belly grew round and she eventually gave birth to a baby, a girl. As soon as this girl came of age, the men took turns copulating with her, just as they had with her mother. And so it went. Every daughter conceived through such mass couplings mothered her own girl, and the cycle continued.

Now there are women in every shabono, and all Yąnomamö trace their ancestry back to both Moonblood and Wabu, though it’s the male line they favor.

Around this time, back when time wasn’t fixed on its single-dimensional trajectory, a piece of the hedu kä misi—the sky layer, the underside of which we see whenever we look up—fell crashing into hei kä misi. The impact was so powerful that the shabono the piece of sky landed on, Amahiri-teri, was knocked all the way through and out the bottom of the layer, finally coming to form a subterranean layer of its own. Unfortunately, the part of hei kä misi that fell through the crater consisted only of the shabono and the surrounding gardens, so the Amahiri-teri have no jungles in which to hunt. Since these people are no badabö, they are able to send their spirits up through the layer separating us. And without jungles to hunt in, they’ve developed an insatiable craving for meat.

Thus the Amahiri-teri routinely rise up from under the ground to snatch and devour the souls of children. Most of the spirits the shamans do battle with in their daily rituals are sent by shamans from rival villages to steal their children’s souls, but every once in a while they’re forced to contend with the cannibalistic Amahiri-teri.

When Yąnomamö die, their buhii, their spirits, rise up through to the surface of the sky layer, hedu kä misi, to the bottom of which are fixed the daytime and nighttime skies as we see them, but the top surface of which mirrors the surface of this layer, with jungles, mountains, streams, and of course Yąnomamö, with their shabonos and gardens. Here too reside the no badabö, but since their essences are mixed they’re somewhat different. Their spirits, the hekura, regularly travel to this layer in forms part animal and part human. It is with the hekura that the shamans commune in their daily sessions with ebene, the green powder they shoot through blowguns into each other’s nostrils.

The shamans imitate particular animals to call forth the corresponding hekura and make requests of them. They even invite the hekura to take up residence inside their bodies—as there seems to be an entirely separate cosmos within their chests and stomachs. This is possible because the hekura, who travel down to earth from high mountains on glittering hammock strings, are quite tiny. With the help of ebene, they appear as bright flashes flitting about like ecstatic butterflies over a summertime feast.

“Sounds a bit like our old notion of fairies,” says the padre. “Fascinating. I’ve heard bits and pieces of this before, but it’s truly fantastic—and it’s quite impressive you were able to pick all of this up in just over a month.”

“Oh, don’t write it down yet,” Lac says. “It’s only preliminary. Even within Bisaasi-teri, there’s all kinds of disagreement over the details. And I’m still struggling with the language—to put it mildly. Lucky for me, they do the rituals and reenact the myths every day when they take their hallucinogens. I think many of the details of the stories actually exists primarily because they’re fun to reenact, and fun to watch. You should see the shamans doing the bit about the first woman stepping on the ends of the vines. Or the brothers shooting their arrows at the moon.”

“Sex and violence and cannibalism. The part about the woman and the fruit—wabu, did you call it?—is familiar-sounding to us Bible readers, no? But there’s no reference to, no awareness of sin or redemption. Sad really.”

The two men sit in chairs, in an office with clean white walls, atop a finished wood floor.

“They also have a story about a flood that rings a bell,” Lac says. “When they realized I was beginning to understand a lot of what they were saying, they started asking me if I had drowned and been reincarnated. They explained there was once a great flood that washed away entire villages. Some Yąnomamö survived by finding floating logs to cling to, but they were carried away to the edges of hei kä misi. When they didn’t return, everyone figured they must have drowned. But one of their main deities, Omawä, went to the edge and fished their bodies out of the water. He wrung them out, breathed life back into them, and sent them back home on their floating logs—which may be a reference to the canoes they see Ye’kwana traveling in. Of course, we come by canoe as well. They conclude we must be coming from regions farther from the center of this layer, because we’re even more degenerated from the original form they represent, and our speech is even more ‘crooked,’ as they call it.”

The padre rolls his head back and laughs from his belly. Lac can’t help laughing along. Father Santa Claus here.

“Their myths do seem to capture something of their character,” the padre says, “this theme of a free-for-all with regard to fighting and killing and sex, for instance.”

Lac resists pointing out the ubiquity of this same theme throughout the Old Testament, which to him is evidence that both sources merely reflect the stage of their respective society’s evolution at the time of the stories’ conceptions. He says instead, “It’s not a total free-for-all. They find the Amahiri-teri truly frightening because they feel they’re always at risk of turning to cannibalism themselves—and they find the prospect absolutely loathsome and disgusting. I think that’s why they prefer their meat so well-done. I ate a bloody tenderloin I cut from a tapir I’d shot in front of some of the men. It was barely cooked—how I like it. The men were horrified, accusing me of wanting to become a jaguar, an eater of raw human flesh. So they do have their taboos.”

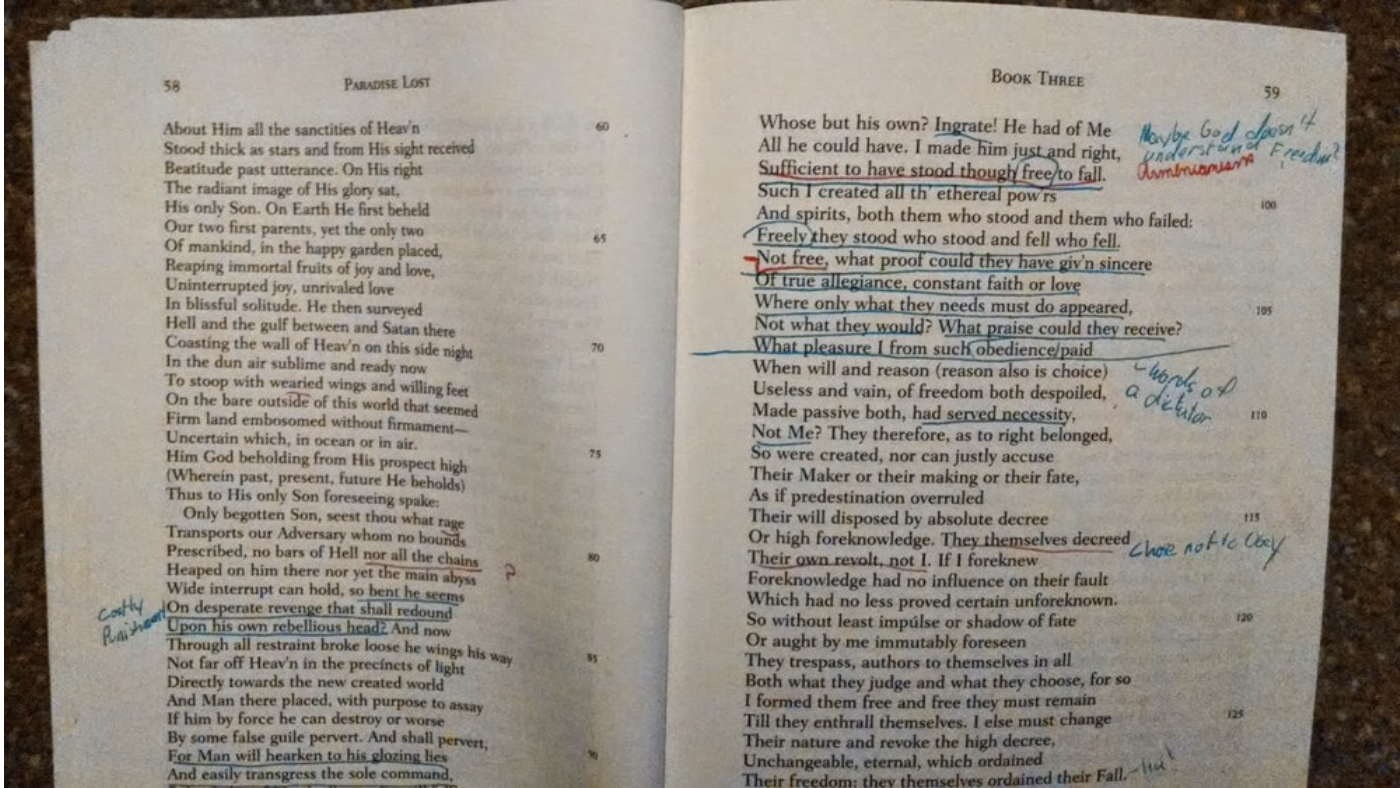

Lac wishes he could add that the moral dimension of the story of Genesis is overstressed. By modern, civilized standards, the original sin stands out as a simple act of disobedience, defiance. You live in paradise, but a lordly presence commands you not to eat fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil: this sounds a bit like, “You have it made, just don’t ask questions.” Or else, “I’ve given you so much, don’t you dare question me!” One could argue you’d have a moral obligation to eat the fruit. Or you could even take morality out of the interpretation altogether and look at the story as an allegory of maturation from a stage of naïve innocence to one of more worldly cynicism, like when your parents can no longer protect you from the harsh realities of the world—in no small part because you insist on going forth to investigate them for yourself.

Had Laura eaten from the Tree of Knowledge when she discovered the other women she encountered at U of M were only there to meet prize marriage prospects? Was that her banishment from paradise? Did I eat the same fruit by coming to Bisaasi-teri and witnessing firsthand how much of what I’d learned from my professors was in dire need of questioning and revision? Of course, I’d eaten that fruit before. We probably all have once or twice by the time we’re approaching our thirties.

“Taboos and temptations, indeed,” says the padre. “I wonder,” he adds somberly, “what the final mix of beliefs will look like when my time in the territory has come to an end. Hermano Mertens says the Indians he speaks to across the river from you at Mavaca confuse the name Jesus with the name of one of the figures from their myths.”

“Yes, Yoawä—he’s Omawä’s twin brother.” Lac forbears to add that Yoawä is usually the uglier, clumsier, and more foolish of the pair in the stories. But he does say, “Chuck Clemens did once tell me it was all but impossible to convince the Yąnomamö to reject their religion wholesale. The best he could hope for was to see them incorporate the Bible stories into their own stories about the no badabö.”

The kindly padre chuckles. “Ah, that’s how it looks for the first generation. For the children, the balance will have shifted. For the grandchildren, the stories they tell now will be mere folktales—if they’re not entirely forgotten… I can tell that prospect disturbs you. You find fascination in their culture and their way of life. That’s only natural, you being an anthropologist. And your friend is a Protestant. Here we all are in the jungle, battling it out for the savages’ souls. It was ever thus.”

It was not ever thus, Lac thinks. Those savages used to be exterminated by the hundreds for their land, and for their madohe if they had any. People like me were called heretics and burned at the stake. “One of my informants,” he says, “tells me the hekura find it repulsive when humans have sex. He says he’d like to become a shabori, a shaman, himself, but the initiation entails a year of fasting, which reduces the men to walking skeletons, and a year of sexual abstinence. See, to become hekura oneself, you must first invite the hekura spirits into your chest. And they won’t come if you’re fooling around in hammocks or in the back of the garden with women. The hekura believe sex is shami, filthy. You can’t help but heed the similarity with the English word shame.”

The padre laughs and Lac laughs easily alongside him. There’s no tension between him and this priest, obviously a beneficent man. “I suspect,” Lac says, “the older shabori tell the initiates the hekura think sex is shami because they want to neutralize the competition for a year. So many of their disputes are over jealousy, liberties taken with wives, refusals to deliver promised brides.”

“They receive no divine injunction to seek peace and love their fellow man?” the padre asks, though the utterance hovers in the space between question and statement.

“That’s not entirely true. One of my informants tells me they face judgement when they die. A figure named Wadawadariwä asks if they’ve been generous in mortal life. If they say yes, they’re admitted into hedu, the higher layer. But if not they are sent to Shobari Waka, a place of fire.” Lac pauses to let his Spanish catch up with his thoughts. The Yąnomamö terms keep getting him tangled up, making him lose track of which word fits with which language. He imagines that, while in his mind he’s toggling back and forth between each tongue somewhat seamlessly, in reality he’s probably speaking a nearly incoherent jumble. “But when I asked the man how seriously the Yąnomamö take this threat of a fiery afterlife, he laughed. You see, Wadawadariwä is a moron, and everyone knows to tell him what he wants to hear. They lie. He has no way of knowing the truth.”

Now the padre’s attention is piercing; he’s taking note. Lac half expects him to get up from his straight-backed wicker chair and find a notepad to jot down what he’s heard. Nice work, Shackley. You just helped the Church make inroads toward frightening the Yąnomamö into accepting a new set of doctrines.

“Curious that they’d have such a belief,” the padre says. “I wonder if it’s not a vestige of some long-ago contact with Christians—or some rumor passed along from neighboring tribes that got incorporated into their mythology in a lukewarm fashion.”

“I had the same thought. The biggest question I have now though is whether my one informant is giving me reliable information. You work with the Yąnomamö; you know how mischievous they are. They all want to stay close to me for the prime access to trade goods, but I can tell they don’t think much of me. Ha! I’m no better off than Wadawadariwä, an idiot they’ll say anything to to get what they want.”

This sets the padre to shuddering with laughter again. “Oh, my friend, what do you expect? You show up, build a mud hut, and start following them around all day, pestering them with questions. You can see why they’d be confused about your relative standing. But I understand you want to report on their culture and their way of life. Maybe you really are doing that the most effective way, but maybe you could learn just as much while being much more comfortable.” He stretches and swings his arm in a gesture encompassing his own living conditions. “It’s hard to say. But since the Church’s goal is different—our goal is first to persuade them—we feel it best to establish clear boundaries, clear signals of where we stand, how our societies would fare if forced to battle it out, in a manner of speaking. And battle it out we must, for the sake of their immortal souls.” He makes a face and wiggles his fingers in accompaniment to this last sentiment.

Lac appreciates him making light of such a haughty declamation, but he’s at a loss how to interpret the general message. Does the padre not really believe he has to demonstrate the superiority of his culture if he hopes to save the Yąnomamö’s souls? Or does he simply recognize how grandiose this explanation of his mission must sound to a layman, a scientist no less—or a man aspiring to be one at any rate.

“But naturally we’ve had our difficulties,” the padre continues, pausing to scowl over his interlaced fingers. “I hope however that once we’ve established a regular flight schedule, landing and taking off from Esmeralda, many of those difficulties will be resolved.”

“A regular flight schedule?”

“Yes, we’re negotiating with the Venezuelan Air Force to start making regular flights out here, maybe make some improvements to the air strip. Ha ha. I’m afraid I’m not the adventurer you are, Dr. Shackley. I like my creature comforts, and those comforts are often critical to bringing the natives to God. As Hermano Mertens is discovering now at Boca Mavaca.”

Lac remembers standing knee-deep in the Orinoco, watching smoke twist up in its gnarled narrow column, wondering who it could be, wondering if whoever it was might have some salvation on offer. He’d only been in Bisaasi-teri a few days. It was a rough time. The padre, naturally enough, asked after the lay brother setting up a new mission outpost across the river from Bisaasi-teri soon after they’d introduced themselves. “Honestly,” Lac answered, “I just managed to get my hands on the dugout because the Malarialogìa are trying to get pills to all the villages. It’s a really bad year for malaria. Many of the children of Bisaasi-teri are afflicted. I did hear some rumors about a construction project of some sort going on across the river, but I have yet to visit and check it out for myself.”

“Hermano Mertens had such high hopes for what he could accomplish there,” the padre says now. He pauses. One of the traits that Lac has quickly taken to in the padre is his allowance for periods of silence in conversation. Back in the States, people are so desperate to fill gaps in dialogue that they pounce whenever you stop to mull over a detail of what’s been said. The Yąnomamö are worse still. With them, you can forget the difficulty of getting a word in; every syllable you utter throughout the whole conversation will be edgewise, if not completely overlain. No one ever speaks without two or three other people speaking simultaneously.

The padre is thoughtful, curious, so he offers any interlocutor opportunities for contemplation. Lac is relieved that the one shortwave radio in the region isn’t guarded by a man who’s succumbed to the madness of the jungle, a man who’s filled with delusions and completely unpredictable in his demands and threats, like the ones the Venezuelans downriver had described to him in warning—to encourage him to both watch out for it in others and to avoid succumbing to it himself—a reprising of the warning he originally received from his Uncle Rob when they were trekking across the UP. Lac is glad to have instead found in Padre Morello a man who’s warm, friendly, thoughtful—thoughtful enough to speak clearly and at a measured pace to help Lac keep up with the Spanish—and kind, a perspiring Santa of the tropics, with a round belly, scraggly white beard, and exiguous hair thinning to a blur of floating mist over the crown of his head. The figure he cuts is disarming in every aspect, except the incongruously dark and sharp-angled eyebrows, a touch of Mephistopheles to his otherwise jolly visage.

Still—first Clemens, now Morello, both hard to dislike, both hard to wish away from the jungle, away from the Yąnomamö, whose way of life it is their mission to destroy. Yet how many nights over the past month have I, he thinks, lain awake in my hammock listening to the futile bellicose chants of the village shabori trying to wrest the soul of some child back from the hekura sent by the shabori of some rival village? Every illness is for the Yąnomamö the result of witchcraft. And there’s a reason the demographic age pyramid is so wide at the base and narrow at the top. There are kids everywhere you go, everywhere you look, but how many of them will live long enough to reach the next age block?

As much as Lac abhors the image of so many Yąnomamö kids sitting at desks lined up in neat rows, wearing the modest garb of the mission Indian, he’s begun to see that those kids at least won’t have to worry about missing out on their entire adolescence and adulthood because they picked up a respiratory infection that could easily be cured with the medicine a not-too-distant neighbor has readily on hand.

“You know, every president in the history of Venezuela has attended a Catholic Salesian school,” the padre says. “It shouldn’t be too difficult convincing the officials in Caracas how important it is that we are able to supply ourselves.” He’s talking about his airstrip in Esmeralda. The influx has begun; now it will want to gather momentum. How long before the region bears not even the slightest resemblance to what it is now? How long before Yąnomamöland is a theme park for eager and ingenuous young Jesus lovers?

Soon after he’d docked the new dugout—newly purchased anyway—here at the mission, the padre led him to the office with the shortwave. As both men suspected would be the case, no one answered their calls. Regular check-ins are scheduled for 6 am every day. Outside of that, you’re unlikely to reach anyone. Lac had left Bisaasi-teri with the Malarialogìa men at first light. They said they were returning to Puerto Ayacucho, so Lac agreed to take them as far as Esmeralda after buying their motorized canoe. They passed Ocamo about halfway through the trip, but Lac pressed on to fulfill his promise. He was tempted to stay in Esmeralda, but instead turned around to make sure he could make it back to the mission outpost, with its large black cross prominent against the white gable you could see from the river, before it was too late in the day. He had doubts about his welcome among the Salesians. Had they heard of his dealings with the New Tribes missionaries? Would they somehow guess, perhaps tipped off by his profession, that he was an atheist?

He was in the canoe all day, still feels swimmy in his neck and knees, still feels the vibrating drone of the motor over every inch of his skin, but nowhere so much as in his skull, like a thousand microscopic termites boring into the bone, searching out the pulpy knot behind his eyes. He’s a wraith, wrung of substance, a quivering unsubstantial husk, with heavy eyelids. But all his vitality would return in an instant were he to hear Laura’s voice—or any mere confirmation of her existence on the other side of these machines connecting them through their invisible web of pulsing energy. Just an acknowledgement that while she may not be available at that particular instant, she is still at the compound, clean and safe and well provided for, her and the kids; that would pull him back from what he fears is the brink of being lost to this hallowed out nonexistence forever. They’ll try the radio again before he retires to the hammock he’s hung in the shed where the good padre has let him store his canoe. Their best bet of reaching someone, though, will be in the morning. He can talk to Laura, say his goodbyes to the padre, perhaps set a time for his next visit, and be back to Bisaasi-teri well before noon, before the villagers are done with the day’s gardening, before it’s too sweltering to do anything but gossip and chat.

He yawns. The padre is still talking about the airstrip, about how convenient it will be to them both, about how silly the persistent obstacles and objections are. They’re going to win, Lac thinks: the Catholics. A generation from now there will be but a few scattered villages in the remotest parts of the jungle. The rest of the Yąnomamö will be raised in or near mission schools, getting the same education as all the past presidents of Venezuela. Could I be doing more to stop this? Should I be? At least this man’s motives seem benign, and he’s offering so many children a better chance of reaching adulthood—maybe not the children of this generation but more surely those of the next.

The padre has access to a small airstrip here at Ocamo too, and he’s always sending for more supplies to build up the compound, including the church, the school, the living quarters, and the comedor, which is like a cafeteria. You can’t really get much in, he complained, on the planes that can land here. But it’s the steady trickle that concerns Lac. Morello talks about his role here in the jungle as consisting mainly of helping to incorporate the Indian populations into the larger civilization. Not extermination, of course—we’re past that—but assimilation. It’s either that or they slowly die off as ranchers, loggers, and miners dispossess them of their territories, or poison their water, a piece at a time, introducing them all the while to diseases they have no antibodies to combat, and taking every act of self-defense as a provocation justifying mass slaughter.

The padre wants the Indians to be treated the same as everyone else, afforded all the same rights: a tall order considering Venezuela as a country has a giant inferiority complex when it comes to its own general level of technological advancement. You take some amenity that’s totally lacking in whatever region you’re in, and that’s exactly what the officials, and even the poorest among the citizenry, will insist most vociferously they have on offer, more readily available than anywhere else you may visit in the world. Just say the word. The naked Indians running around in the forests are an embarrassment, so far beneath the lowermost rung on the social ladder they’d need another ladder to reach it, barely more than animals, more like overgrown, furless monkeys. That’s the joke you hear, according to the Malarialogìa men. The funny thing is, to the Yąnomamö, it’s us nabä who are subhuman. Look at all the hair we have on our arms and legs, our chests and backs. We’re the ones who look like monkeys—and feel like monkeys too after spending enough time in the company of these real humans.

Without our dazzling and shiny, noisy and deadly technology, there’d be no way to settle the conflicting views. But we know it will be the nabä ways that spread unremittingly, steamrolling all of Yąnomamöland, not the other way around. Insofar as the padre and his friends are here to ease the transition, saving as many lives as possible from the merciless progress of civilization and all the attendant exploitation and blind destruction, who is Lac to fault him for being inspired by backward beliefs? Of course, it’s not the adoption of nabä ways in general the Salesians hope to facilitate; it’s the ways of the Catholic Church. The Salesians had no interest in the Indians’ plight—particularly not a foot people like the Yąnomamö, living far from the main waterways—until the New Tribes began proselytizing here. The Christians, Lac thinks, are plenty primitive in their own way; they’ve carried on their own internecine wars for centuries.

“Don Pedro will be there when I check in at 6 tomorrow morning. I’ll have him try to reach the institute in Caracas by phone and then patch us through so you can talk to your wife.” The padre pauses thoughtfully, and then, donning a devilish grin, says, “I wonder: you said both you and your wife attended Catholic schools in Michigan. Did you also have a Catholic wedding ceremony?”

Lac appreciates the teasing; the padre is charming enough to pass it off as part of a general spirit of play, one he infuses at well-timed points throughout the conversation. Ah, to speak to a civilized man, Lac savors, whose jokes are in nowise malicious. Smiling, he answers, “Oh, Laura’s mother would never have accepted anything else as binding.” The two men laugh together. “And you?” Lac counters. “How does the Church view your readiness to converse with people of other faiths?”

“Other faiths?” the padre asks skeptically.

So he has guessed I’m an atheist.

“Miraculously enough,” the padre says without waiting for a response, “I’ve just read in our newsletter that the pope recently issued an edict declaring priests are free to pursue open dialogue with Protestants and nonbelievers, and that such exchanges may even bear spiritual fruit in our quest to become closer to God. What this means, my friend, is that I don’t have to feel guilty about enjoying this conversation so much.”

“And many more thereafter I hope.”

The padre smiles, his teeth flashing whiter than his scraggly beard. “You know,” he says, “throughout he war, I lived in the rectory of a church in my hometown near Turin. Now this was Northern Italy, so there were planes flying overhead all the time. We’d often hear their guns rattling like hellish thunder chains in the sky, and on many occasions we felt obliged to rush to the site of a crash. For years, the Germans had the upper hand, but if we found an Allied pilot at the crash site, we’d bring him back to the church, shelter him, and keep him hidden from any patrols. Had we been caught harboring these enemy pilots, feeding them, nursing their injuries, it would have meant the firing squad for us for sure. But what could we do?

“When the tides shifted and it was the Allied forces who dominated the skies, we started finding Axis pilots at the crash sites, and now it was the Allied firing squads we feared.” The padre leans forward with a mischievous twinkle in his eye, holds a hand up to his mouth and whispers, “Here’s the best part: a couple years after the war, I started receiving a pension, an expression of gratitude from the military for what I’d done saving the lives of their pilots, in recognition of what I’d risked—first from the Axis side, then another one later from the Allied side.” He leans away, his head rolling back to release a booming peel of laughter.

Lac too laughs from deep in his belly, wondering, could this story be true? The doubt somehow makes it funnier. Does it even matter? He’s already regretting his plans to leave the mission outpost tomorrow after talking to Laura, already looking forward to his next visit to Ocamo.

The padre has told him he’s writing a book about his life in the jungle, prominently featuring his mission work among the Yąnomamö, and he’s interested in any photographs Lac may be able to provide from his own fieldwork. In exchange, Lac will be free to visit the outpost at Ocamo anytime and make use of the shortwave. He will also be free to store extra supplies and fuel for his dugout’s motor—which will make it easier for him to reach all the towns downstream.

You help me with my book; I’ll help you with yours. Sounds like an excellent bargain to me. But now that you have all these ways of reaching and communicating with the world outside the Yąnomamö’s, you really need to forget about them and get back to work.

*

“—chlan –ell me –u’re alight.” Laura’s voice. English. Bliss.

One candle bowing across the vast distance to light another. The hollowness inside him fills with the warm dancing glow.

Padre Morello discreetly backs out of the room upon hearing the voice come through, and Lac is grateful because he has to choke back a sob and draw in a deliberately measured breath before he can say, “I’m alright Laura. Healthy and in one piece. Though I’ve lost a bunch of weight. How are you and the kids?”

“Healthy and in one piece. They miss you. I think we’re all feeling a little trapped here. There’s another family, though, the Hofstetters—they’ve been a godsend.”

Lac’s mind seamlessly mends the lacunae in the transmission—one of the easier linguistic exercises he’s been put to lately—but every missing syllable elevates his heartrate. He leans forward until his cheek is almost touching the surface of the contraption. He asks, “Are you getting everything you need by way of supplies and groceries?” He feels a pang in recognition of his own pretense at having any influence whatsoever over his family’s provisioning; the question is really a plea for reassurance.

“The Hofstetters have been taking us in their car every week to a grocery store down in the city.” Lac is already imagining a strapping husband, disenchanted with marriage, bored with his wife; he’d be some kind of prestigious scientist no doubt, handsome, over six feet. “Dominic had a fever last week, but it went down after we gave him some aspirin and put him to bed.” We? “He misses French fries, says the ones here aren’t right. He wants McDonalds.”

Lac decides to break the news preemptively, before she has a chance to mention the plan for them to come live with him in the field. “Laura, I have some bad news. The conditions are more prim… it’s rougher than I anticipated.” He proceeds with a bowdlerized version of his misadventures among the Yąnomamö to date, adding that with time he should be able to learn the ropes of the culture and secure regular access to everything they need. “Don’t worry, honey, I’m through the most risky part myself, but even I have to be cautious at all times. I need to make absolutely sure you’ll all be safe before I bring you here.”

“Are the Indians dangerous?” she asks innocently. “When they’re demanding your trade goods like you described, do they ever threaten you?”

“Oh yes.” She knows I’m holding back, he thinks. Am I just making her worry even more? He hurries to add, “They’re full of bluster and machismo. It was intimidating at first, but I picked up on the fact that they’re mostly bluffing.”

“Mostly?”

“You have to understand, all the men are really short. If they get too aggressive I can stand looking down at them. Ha. It’s the first time in my life I’ve been the tallest guy around. And the key I’ve found is to stand your ground, not budge, make sure it’s known to everyone that you’re no easy mark. Now I worry more about the kids making off with anything I leave out in the open.” He turns away and curses himself. Until that last sentence, he’d managed to stick to the technical truth, however misleading the delivery. But he intuited a need in Laura for him to segue onto a more trivial threat, so he brought up the kids, even though it’s the grown men who have the stickiest fingers.

So now I’m officially lying to my wife; I got carried away weaving true threads into a curtain of falsehood and I lost sight of which threads were which. Now I can’t pull out that last thread without the whole thing unraveling, revealing the stark reality. He foresees being haunted by the guilt from his little fib for weeks, or until he’s able to show her firsthand that he really is safe, safe enough to keep her and the kids safe too.

He’s got his work cut out.

*

Padre Morello sees at a glance that Lac has no wish to speak; he makes no effort to continue the conversation from the night before, though doing so would be in keeping with his natural disposition. The men exchange a few words as the padre guides him part of the way back to the shed, where Lac will repack his belongings, do some preventative maintenance on his motor—or pretend to, as he knows embarrassingly little about engines, for a Shackely—and drag the dugout down to the riverbank for the trip back to Bisaasi-teri, back to his hut, back to Rowahirawa and all the others. Rowahirawa, formerly Waddu-ewantow, has taken over the role of chief informant, even though Lac still reckons the chances that he’ll turn violent toward him someday rather high.

The padre never asked him questions like that, about how much danger he felt he was in. That’s the other reason for recreating your own cultural surroundings, or at least a simulacrum of them, when you come to live in this territory—the safety. The dogs living at the Ocamo outpost would alert the inhabitants of any unwanted guests, and the offer of rich food would make it relatively easy to demand visitors disarm themselves before entering the area. Morello had focused on the symbolism, the message sent to the natives about how much more advanced our ways are than theirs, but what if the real reason was more practical, myopic even? You’d have to be insane to come out here and live next to one of their shabonos in a dank and gloomy mud hut. By contrast, even the creak of the wood floor beneath his feet in this place speaks of deliverance.

If it ever gets too bad, he thinks, I’m not too proud to come back here and hole up with the padre. He’ll be able to arrange transportation out of the territory—if it comes to that. “The people of Bisaasi-teri are talking about some trouble brewing to the south of them,” Lac says without having decided to speak.

“Ah, I’ve heard that the Yąnomamö often attack one another’s villages.” Lac can tell the padre has more to add but decides against it, maybe to let Lac finish his thought.

“My first day in the village, I ducked under the outside edge of the wall and stood up to see a dozen arrows drawn back and aimed at my face. I learned later that the Patanowä-teri were visiting to try to form a trading partnership with Bisaasi-teri, and that’s when the men from a third village, Monou-teri, attacked and stole seven of the Patanowä-teri women. The Patanowä-teri in turn went to Monou-teri, less than a day’s walk, and challenged them to a chest-pounding tournament, which they must’ve won because they returned to Bisaasi-teri with five of the seven women.”

The padre nods in thoughtful silence as he walks alongside Lac, who has an inchoate sense of remorse at relaying these most unsavory of his research subjects’ deeds to a representative of the Church. “When Clemens and I arrived, we spooked them. The headman of the Monou-teri had been incensed and swore he’d take vengeance, and the two groups at Bisaasi-teri feared he was making good on his vow. For days, I looked around and it was obvious that something had them on edge, but it wasn’t like I had a baseline to compare their moods against. When the Patanowä-teri left after two days, though, I noted the diminished numbers.”

“You know,” the padre says, “if things get too tense at the village, you’re always welcome to stay here for a while.” This echo of his own earlier thought floods Lac with gratitude. He remembers once silently declaring that he’d never say a word against Chuck Clemens; he now has the same conviction about Padre Morello, though in this case it’s more of the moment, whereas with Clemens, well, he’s still sure he’ll never have anything bad to say about the man.

“I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that, Padre. I’m not expecting it to come to that, but it’s reassuring to know I have a friend to turn to if it does.”

The men shake hands. Lac continues on to the shed and his dugout canoe, while the padre goes back to his day, back to his routine as the head of the mission, directing the ghostly white-clad sisters, feeding and clothing the Indians, swaddled in his nimbus of mirth, like a saint from a bygone era. Isn’t everything out here from one bygone era or another, Lac thinks, including you? He chuckles at the thought, then comes abruptly to the verge of tears—because it’s a joke Laura would enjoy, but he’ll almost certainly have forgotten it by the time he talks to her again.

*

Lac returns in time for another commotion inside Bisaasi-teri’s main shabono. Until docking his canoe, he’d been considering landing on the far shore and journeying inland to introduce himself to the Dutch lay brother who’s building a comedor across the river to attract the Yąnomamö for food and proselytizing. It’ll have to wait for another day. Lac already feels guilty for having been away for so long, a day and a half, imagining the villagers to have engaged in myriad secret rites while he was downriver, or merely some magnificent ceremony no outsider had ever witnessed. Smiling bitterly, bracing himself for whatever chaos he’s about to thrust himself into, he thinks: every ceremony they perform has never been seen by outsiders; the big secret is that they’re not like you’d imagine; they’re like nothing so much as a bunch of overgrown boys getting high and playing an elaborate game of make-believe, boys who could throw a tantrum at random and end up maiming or killing someone, starting a war of axes and machetes, bows and arrows.

He squats under the outermost edge of the thatched roof, sidling and bobbing his way into the headman’s house, where he sees a very pregnant Nakaweshimi, the eldest wife. Since he’s begun addressing the headman with a term that means older brother, he’s obliged to likewise refer to Nakaweshimi as kin, as a sister. “Sister,” he calls to her. “I’ve returned to your shabono. I’m glad to see you. What is happening? What is causing excitement?” Not much like her fellow Yąnomamö speak to her, but they’ve learned to give him extra leeway in matters of speech and etiquette, like you would the village idiot. He’s even been trying to get everyone to tell him all their names, this addled-brained nabä.

Nakaweshimi nearly smiles upon seeing him—at least he thinks she does—but then waves him off. “Rowahirawa will tell you what Towahowä has done now,” she says. Her expression baffles him, showing an undercurrent of deep concern overlain with restrained merriment, like she may have almost laughed. Could she be that happy to see me, he wonders, maybe because she thinks I’ll ward off the raiders with my shotgun and other articles of nabä magic? Or maybe I’m such an object of derision the jokes following in my wake set people to laughing whenever they see me.

He continues through the house out into the plaza, sees the men, some squatting, others standing, pacing. High above them, he looks out to see the thick blur of white mist clinging to the nearly black leaves of the otherworldly canopy and is struck by the devastating beauty, feeling a pang he can’t immediately source and doesn’t have the time to track down. The syllables and words of the men he’s approaching rise up in a cloud around him, a blinding vortex that simultaneously sweeps up the identifiable scents of individual men, bearing aloft the broken debris of shattered meanings, all the pieces just beyond his reach. Straining, he lays a finger on one, then another. He envies these men, naked but for strings, arm bands, sticks driven through their ears, their faces demoniacally distorted by the thick wads of green tobacco tucked behind their bottom lips—envies them because the words swirling away from him flow into their ears in orderly streams.

He sees a squatting man scratch the bottom side of his up-tied penis; another spits, almost hitting a companion’s foot. They’re discussing war and strategy, but we’re a long way from the likes of Churchill and Roosevelt—and yet, probably not as far as us nabä might like to think. Bahikoawa is telling them about his relationship to some man from Monou-teri: he lives in a different village and yet descends from the same male progenitor, meaning they’re of the same lineage. Lac reaches for his back pocket but finds it empty, his notebook, he then recalls, still tucked in a backpack full of items he brought along for the trip to Ocamo.

When the men finally notice Lac’s presence—or finally let on that they’ve noticed him, some of them walk over with greetings of shori, brother-in-law, asking after his efforts to procure more of his splendid nabä trade goods, which they’re sure he’ll want to be generous in divvying out among them. He haltingly replies that he was merely visiting Iyäwei-teri and the other nabä who lives there and is building a great house. He adds that he asked this other nabä to bring him back some medicines—a word borrowed from Spanish, with some distorting effects—he can administer to the Yąnomamö, but it will be some time before they arrive. They respond with aweis and tongue clicks. One man, a young boy really, tells Lac to give him a machete in the meantime—“and be quick about it!”

Ma. Get your own machete.

Among the Yąnomamö, Lac has learned, it’s seen as stingy, almost intolerably so, not to give someone an item he requests. What they normally give each other, though, is tobacco—often handing over the rolled wads already in their own mouths—germ theory still being millennia in the future, or at least a few years of acculturation at the hands of the missionaries. Lac has to appreciate his madohe make him rich, after a fashion, but his refusal to give them away freely makes him a deviant, a sort of reprobate. They don’t exactly condemn him as such. They struggle to work out the proper attitude to have toward him, just as he does toward them. The culture has no categories to accommodate the bizarre scenario in which an outsider in possession of so many valuable goods comes to live among them.

For the most part, they make allowances; they’re flexible enough to recognize the special circumstance. They tolerate his egregious tight-fistedness—what do you expect from a subhuman? And this particular subhuman appears to be trying to learn what it means to be a real human, translated Yąnomamö. Why else would he be so determined to speak their language? Though they seem to think there’s only one language with varying degrees of crookedness. The Yąnomamö to the south speak a crooked dialect for instance, but at least it’s not so crooked as to be indecipherable. Lac must have traveled far beyond those southern villages when he was washed to the edge of the earth by the Great Flood. Really, though, Lac isn’t sure how to gauge what percentage of the villagers actually believes this story, or to what degree they believe it. He’s noted a few times that their beliefs in general seem to be malleable, changing according to the demands of the situation.

Their attitudes toward the Patanowä-teri, for example, have undergone a dramatic shift in the brief time he’s been among them. The Patanowä-teri had come to attend a feast at Bahikoawa’s invitation, hoping to establish regular trade in goods like bows, clay pots, dogs, tobacco, and ebene—or rather the hisiomo seeds used to make it. The Monou-teri, meanwhile, were invited to be fellow guests at the feast, but on their way to Bisaasi-teri they happened upon those seven Patanowä-teri women hiding in the forest, a common precaution, Lac’s been told, to keep them safe from the still suspect host villagers. The Monou-teri couldn’t resist. This led to the chest-pounding duel he’d heard about, though it must have been several separate duels, more like a tournament, the outcome of which was that the Patanowä-teri returned to Bisaasi-teri with five of the seven women, just before Lac and Clemens arrived. The Patanowä-teri then left the village early to avoid further trouble with the Monou-teri, who, if he’s hearing correctly, are now determined to raid the Patanowä-teri at their shabono on the Shanishani River. This despite their having come out ahead by two women.

Now, even though the Patanowä-teri have in no way wronged the people of Bisaasi-teri, Bahikoawa is considering whether he and some of the other men should accompany the Monou-teri on their raid. It seems Bahikoawa is related to the headman of Monou-teri, the one who’s causing all the trouble. This man is waiteri: angry or aggressive, eager to project an air of menace and invincibility, traits considered to be manly virtues rather than political liabilities.

Bahikoawa, it seems, is related to many of the Patanowä-teri as well, but more distantly. The men argue over whether Towahowä, the Monou-teri headman, is justified in launching the raid—not in the moral sense, but in a strategic one—and over whether they should send someone to participate. Bahikoawa, drawing on the juice from his tabacco, looks genuinely distraught, like he’s being forced to choose between two brothers, and Lac feels an upwelling of sympathy. He couldn’t speak for anyone else in any of these villages; he’d be loath to turn his back to any of them. Bahikoawa, on the other hand, is a good man; it’s plain for anyone to see. He also appears to be sick. He keeps clutching his side, as though he’s having sharp pains in his abdomen. Fortunately, the war counsel is breaking up, partly in response to Lac showing up to distract them.

The men have all kinds of questions about the villagers at Ocamo, the Iyäwei-teri, almost none of which Lac can answer: How are their gardens producing? Was everyone at the shabono, or were some of them off hunting? Did they appear well-supplied with tobacco? Lac, realizing he could have easily stopped to check in with the villagers—he’ll want their genealogical information too at some point—tries to explain that he merely went for a chance to speak with his wife and ask after his children. When they assume, naturally enough, his wife must be living at Iyäwei-teri, he’s at a loss as to how he can even begin to explain she’s somewhere else.

Lac asks where Rowahirawa is: out hunting for basho for his in-laws. So there’s little chance of clearing things up about where Laura is and why Lac could nonetheless speak to her from Ocamo. Lac decides to step away and go to his hut to relax for a bit before starting his interviews and surveys again. He’s shocked by his own oversight, not anticipating that the people of Bisaasi-teri would be eager to hear about what’s going on at Iyäwei-teri. Travelers are the Yąnomamö’s version of newspapers; it’s how they know what’s brewing at Monou-teri; it’s the only way for them to know what’s going on in the wider world—their own wider world anyway. But is what the Bisaasi-teri are after best characterized as news, gossip, or military intel?

At some point, it’s disturbingly easy to imagine, he could unwittingly instigate an intervillage attack simply by relaying the right information—or rather the wrong information. Lac is also amazed by the Yąnomamö’s agility in shifting alliances, and he can’t figure out how to square it with his knowledge about tribal societies vis-à-vis warfare, which is thought to begin when a society reaches a stage in its evolution when the people start to rely on certain types of key resources like cultivable land, potable water, or ready access to game. Intergroup conflicts then intensify when the key resources take on more symbolic than strategic meanings, as when they’re used as currency or as indicators of status. Think gold and diamonds. But Bisaasi-teri was working to establish trade relations with Patanowä-teri when the Monou-teri headman, in a brazen breach of diplomacy, instigated hostilities.

What resources, he wonders as he steps into his hut, can they possibly be fighting over?

If anything, the fighting seems to be further limiting their access to the goods they may otherwise procure through trade. And why should the Bisaasi-teri men consider sending a contingent to represent their village in the raid? When the first offense occurred, the Bisaasi-teri were seeking to strengthen their ties to Patanowä-teri, and Bahikoawa’s lineage is present in both villages, so why bother picking a side? Why not sit out the fight? What do they hope to gain?

Lac lies back in his hammock, trying to make sense of it. He could easily fall asleep.

As he was preparing to board the ship in New York with Laura and the kids and all the supplies he was going to take with him into the field, he’d read in a newspaper about the U.S. sending military advisors to Southeast Asia, another jungle region, to support a group of people resisting the advance of communism. The Soviet Union apparently has already established a foothold in the country by supporting a rival group, the Vietcong. The threat of a proxy war between the great powers looms.

What resources are the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. fighting over? It seems to Lac to be much more about ideas: capitalism vs. communism. Is it only nations at the most advanced stages of technological advancement that battle over ideologies and economic systems? Dozing off, Lac’s last thought is that for the Bisaasi-teri men at least, the real motivation seems to be the opportunity to assert their own impunity alongside their readiness to punish rivals for any miniscule offense. It’s about projecting an air of superiority, acquiring prestige, for yourself, your village, your lineage, your tribe, your nation, your very way of life.

*

He dozes for maybe twenty minutes, his eagerness to work blunting the edge of his now-chronic exhaustion. Overnighting at the mission afforded him a superb night of sleep, comparatively. The Yąnomamö don’t keep to the strict schedules Westerners do; they have no qualms about late-night visits, even if those visits require rousing the visitee from a deep slumber. They do fortunately happen to be adept at midday dozes, a skill they like to practice during the day’s most oppressively hot stretches, when doing much of anything else is a loathsome prospect. Lac has adapted quickly, hence the short nap when he really felt like a longer sleep.

One good stretch of uninterrupted sleep, he thinks, hardly makes up for the weeks of erratic events, bizarre occurrences, and anxiety-fueled insomnia. When I finally leave this place, in just over a year from now, I may spend the first month home doing nothing but sleeping. What bliss. For now, though, he has work to do, and thanks to the encroachments into Yąnomamöland by the New Tribes and the Salesians, he’s on a diminishing timetable. Already, it will be difficult to tell how closely the population structures he uncovers reflect outside influences versus the true nature of tribal life in the jungle. He keeps hearing about more remote villages to the South, near the headwaters of the Mavaca, where there’s supposedly a single shabono housing over twice as many people as Bisaasi-teri. According to his main informant at least. According to his whilom persecutor, his bully, his now sometimes friend—as reticent as he’s learned to be in applying that term, and as wary as he’s become in allowing for that sentiment.

It’s still hot. The trip from Ocamo took a little over six hours, twice as long coming upriver than it was going downstream. He’s hungry, but the lackluster range of choices on offer dulls his appetite. He guesses that in the little over a month he’s been in the field, he’s lost between ten and fifteen pounds. He may never successfully remove the crusty, bug-bitten, sticky film clinging to his body; he imagines Laura catching a first whiff of him when they’re finally reunited and bursting into tears.

But I’m on to something, he thinks as he stands and moves to the table. From his discussions with Rowahirawa, he’s learned that the proscription against voicing names isn’t a taboo per se; saying someone’s name aloud is more like taking a great liberty with that person, much the way Westerners would think of being groped in public, an outrageous gesture of disrespect. But, while it may be grossly offensive to run your hands over a stranger, or even an intimate if it’s in a public setting, you can often get away with more subtle displays of affection; you can touch another person’s arm, say, or her shoulder; you could reach over and touch her hand.

Remembering a night with Laura, back before Dominic was born, Lac has one of his rare flickers of sexual arousal, a flash of a scene overflowing with the promise sensual indulgence. Lac looks around his hut; it’s only ever moments before someone arrives. He’s probably only been left alone this long because of the excitement in the shabono over the impending conflict to the east. He’s yet to see a single Yąnomamö man or woman masturbate, he notes, but the gardening time of day is when the jokes and all the innuendo he can’t decode suggest is the time for trysting. Someone’s always gone missing, and then it’s discovered someone else has gone missing at the same time. Lac’s never witnessed these paired abscondings. Sexuality is notoriously tricky for ethnographers to study, a certain degree of discretion being universal across cultures. People like to do it in private. It seems this is particularly true of the Yąnomamö, if for no other reason than that they fear detection by a jealous husband.

And Lac himself?

He’s awoken in his hammock from dreams of lying alongside Laura on the smoothest, cleanest sheets he’s ever felt—awoken in a compromised state his unannounced Yąnomamö visitor took no apparent notice of. He feels an ever-present pressure crying out for release, but the conditions could hardly be less conducive to the proper performance of such routine maintenance tasks. He’s never alone, never anything less than filthy—sticky, slimy, and moderately uncomfortable—and the forced press of Yąnomamö bodies he keeps being subjected to has an effect the opposite of sensual. So he feels the tension, physiologically, from having gone so long without release, but nothing in the field comes close to turning him on.

None of the Yąnomamö women? Not one?

There’s something vaguely troubling to Lac about this, as it seems to have little to do with his devotion to Laura. His devotion to Laura manifests itself through his resistance to temptation, not its absence. So why is he, an aspirant acolyte of Boas, not attracted to, not sexually aroused by any of the women among this unique group of his fellow humans?

Shunning the implications, his mind takes him back in time to some key moments in his budding intimacy with the woman he’d go on to marry. He would enjoy hanging out in his hut and reminiscing like this, but sensing its futility, he decides instead to get to work, get to making something worthwhile out of this expedition, this traumatizing debacle of a first crack at ethnographic fieldwork, get to securing his prospects for a decent career—oh, the bombshells he’ll be dropping on his colleagues—get to securing a living for his family and a valuable contribution to the discipline, his legacy. Maybe Bess and Laura are right, he thinks; maybe I’m incapable of accepting a cause as lost; maybe I have something to prove, a vestige of some unsettled conflict with my father and brothers. So be it. I may as well turn it into something worthwhile.

*

At last, he writes later that night, I’ve succeeded in getting some names, and I’ve begun to fill in some genealogical graphs. My work has begun, my real work. What I couldn’t have known when I decided to study the Yąnomamö was that I would be working with the most frustratingly recalcitrant people ever encountered by an anthropologist. My project of gathering names will be a complex and deeply fraught endeavor, and every mistake will put me in danger: my subjects getting angry with me at best, violent at worst. It doesn’t help that the Yąnomamö also happen to be consummate practical jokers, who see having an ignorant and dimwitted nabä around, someone who’s just learning the basics of their language, as an irresistible opportunity.

One man will casually point me toward another, instructing me to say, “Tokowanarawa, wa waridiwa no modohawa.” When I go to the second man and repeat the phrase, careful to get the diction right, he is furious and begins waving his arms and threatening me—and rightly so since I’ve just addressed him by name and told him he’s ugly. Here’s the peculiar thing: even though the man I’ve insulted witnessed the exchange with the first man—even though he knows I’m merely relaying a message—he directs his anger at me and not the actual source of the insult, a man who is by now in hysterics over the drama he’s instigated. (This prank, along with a few minor variations at other times, was pulled on me by one of my most reliable informants, Rowahirawa.)

The Yąnomamö love drama. They love trouble. And I have to be careful not to give in to my inclination to respond to angry subjects by offering them madohe to make amends, a response that would make (and to some degree has already made) me appear cowed, and cowardly, encouraging and emboldening them to make more displays and more threats. But, as delicate as one must be in negotiating the intricacies of the name customs, I’ve managed to uncover some underlying threads of logic to them. The worst offense when it comes to names, for instance, is to publicly say those of recently deceased relatives. The second worst offense—which is probably just as dangerous to commit—is using the name of a browähäwä, a politically prominent man, most of whom (all?) are also waiteri, warriors.

What I’ve observed, however, is that when the Yąnomamö refer to one of these men, they usually do so through teknonymy: they imply his identity through his relationship to someone safe to name. They’d never say the headman Bahikoawa’s name out loud, but instead refer to him as “the father of Sarimi,” his daughter. I can therefore begin building out my genealogies in a similar fashion, starting with the names of children and working my way up. Over time, I may light on new methods that will bring me closer to the names of the browähäwä and the ancestors, but by then I hope to already have their relationships with all the other villagers mapped out using the same sort of teknonymy as the Yąnomamö use themselves.

My plan is to create a standard list of questions and then to interview as many of the villagers as possible, offering them fish hooks or nylon line or disinfectant eye drops as payment. I’ll interview them individually, so there will be no witnesses to any sharing of sensitive information, and I’ll encourage each interviewee to whisper the names in my ear, as a demonstration of how much I personally respect the individuals being named. Still, I don’t expect to be able to draw complete charts the first time around. This first round will be more like tryouts. I’ll be looking to identify the most helpful, articulate, and reliable informants, an exercise that will involve checking each candidate’s answers against the others’.

For round two, I’ll stick to the individuals who most readily provided me with the best information in round one. And I’ll offer them more valuable trade goods in exchange for their help: machetes, axes, game meat. Over time, as I build up some trust and establish rapport, I’ll start pressing them for the more sensitive names. I’m estimating that by mid-March I should have everyone’s name on record, along with a chart that fits each village member into the kinship network. I’ll be able to pass these charts along to Dr. Nelson when he and his team arrive for their genetic research next year. And the information will also form the basis of any theorizing on my own part about the nature and evolution of larger societal patterns. At the same time, it will give me a head start on the charts for neighboring villages, and subsequently for the more remote ones I hope to visit on future expeditions.

Lac closes the notebook, leans his head back, and sighs. A lot of things that could very easily go wrong will need to go right for this plan to work. Thinking about all the variables is overwhelming. But what really scares him now is the thought of those future expeditions, of having to return to the jungle once he’s made it out.

If he makes it out.

***

Find my author page.

Posts on Napoleon Chagnon:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

And:

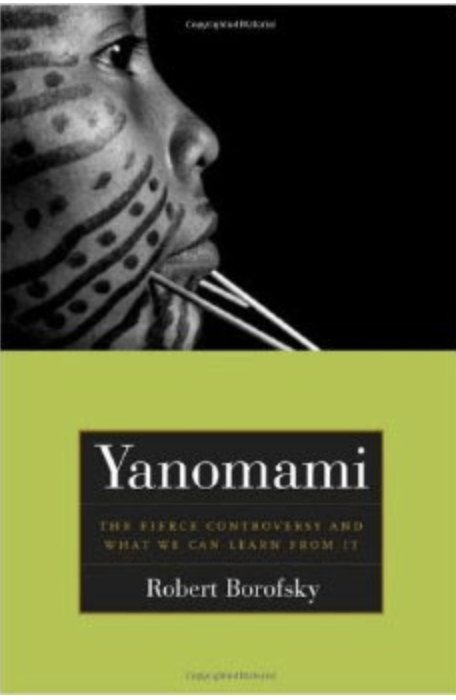

JUST ANOTHER PIECE OF SLEAZE: THE REAL LESSON OF ROBERT BOROFSKY'S "FIERCE CONTROVERSY"

Why Tamsin Shaw Imagines the Psychologists Are Taking Power

Upon first reading Shaw’s piece, I dismissed it as a particularly unscrupulous bit of interdepartmental tribalism—a philosopher bemoaning the encroachment by pesky upstart scientists into what was formerly the bailiwick of philosophers. But then a line in Shaw’s attempted rebuttal of Haidt and Pinker’s letter sent me back to the original essay, and this time around I recognized it as a manifestation of a more widespread trend among scholars, and a rather unscholarly one at that.

Tamsin Shaw’s essay in the February 25th issue of The New York Review of Books, provocatively titled “The Psychologists Take Power,” is no more scholarly than your average political attack ad, nor is it any more credible. (The article is available online, but I won’t lend it further visibility to search engines by linking to it here.) Two of the psychologists maligned in the essay, Jonathan Haidt and Steven Pinker, recently contributed a letter to the editors which effectively highlights Shaw’s faulty reasoning and myriad distortions, describing how she “prosecutes her case by citation-free attribution, spurious dichotomies, and standards of guilt by association that make Joseph McCarthy look like Sherlock Holmes” (82).

Upon first reading Shaw’s piece, I dismissed it as a particularly unscrupulous bit of interdepartmental tribalism—a philosopher bemoaning the encroachment by pesky upstart scientists into what was formerly the bailiwick of philosophers. But then a line in Shaw’s attempted rebuttal of Haidt and Pinker’s letter sent me back to the original essay, and this time around I recognized it as a manifestation of a more widespread trend among scholars, and a rather unscholarly one at that.

Shaw begins her article by accusing a handful of psychologists of exceeding the bounds of their official remit. These researchers have risen to prominence in recent years through their studies into human morality. But now, instead of restricting themselves, as responsible scientists would, to describing how we make moral judgements and attempting to explain why we respond to moral dilemmas the way we do, these psychologists have begun arrogating moral authority to themselves. They’ve begun, in other words, trying to tell us how we should reason morally—according to Shaw anyway. Her article then progresses through shady innuendo and arguments based on what Haidt and Pinker call “guilt through imaginability” to connect this group of authors to the CIA’s program of “enhanced interrogation,” i.e. torture, which culminated in such atrocities as those committed in the prisons at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay.

Shaw’s sole piece of evidence comes from a report that was commissioned by the American Psychological Association. David Hoffman and his fellow investigators did indeed find that two members of the APA played a critical role in developing the interrogation methods used by the CIA, and they had the sanction of top officials. Neither of the two, however, and none of those officials authored any of the books on moral psychology that Shaw is supposedly reviewing. In the report’s conclusion, the investigators describe the responses of clinical psychologists who “feel physically sick when they think about the involvement of psychologists intentionally using harsh interrogation techniques.” Shaw writes,

It is easy to imagine the psychologists who claim to be moral experts dismissing such a reaction as an unreliable “gut response” that must be overridden by more sophisticated reasoning. But a thorough distrust of rapid, emotional responses might well leave human beings without a moral compass sufficiently strong to guide them through times of crisis, when our judgement is most severely challenged, or to compete with powerful nonmoral motivations. (39)

What she’s referring to here is the two-system model of moral reasoning which posits a rapid, intuitive system, programmed in large part by our genetic inheritance but with some cultural variation in its expression, matched against a more effort-based, cerebral system that requires the application of complex reasoning.

But it must be noted that nowhere does any of the authors she’s reviewing make a case for a “thorough distrust of rapid, emotional responses.” Their positions are far more nuanced, and Haidt in fact argues in his book The Righteous Mind that liberals could benefit from paying more heed to some of their moral instincts—a case that Shaw herself summarizes in her essay when she’s trying to paint him as an overly “didactic” conservative.

Haidt and Pinker’s response to Shaw’s argument by imaginability was to simply ask the other five authors she insinuates support torture whether they indeed reacted the way she describes. They write, “The results: seven out of seven said ‘no’” (82). These authors’ further responses to the question offer a good opportunity to expose just how off-base Shaw’s simplistic characterizations are.

None of these psychologists believes that a reaction of physical revulsion must be overridden or should be thoroughly distrusted. But several pointed out that in the past, people have felt physically sick upon contemplating homosexuality, interracial marriage, vaccination, and other morally unexceptionable acts, so gut feelings alone cannot constitute a “moral compass.” Nor is the case against “enhanced interrogation” so fragile, as Shaw implies, that it has to rest on gut feelings: the moral arguments against torture are overwhelming. So while primitive physical revulsion may serve as an early warning signal indicating that some practice calls for moral scrutiny, it is “the more sophisticated reasoning” that should guide us through times of crisis. (82-emphasis in original)

One phrase that should stand out here is “the moral arguments against torture are overwhelming.” Shaw is supposedly writing about a takeover by psychologists who advocate torture—but none of them actually advocates torture. And, having read four of the six books she covers, I can aver that this response was entirely predictable based on what the authors had written. So why does Shaw attempt to mislead her readers?

The false implication that the authors she’s reviewing support torture isn’t the only central premise of Shaw’s essay that’s simply wrong; if these psychologists really are trying to take power, as she claims, that’s news to them. Haidt and Pinker begin their rebuttal by pointing out that “Shaw can cite no psychologist who claims special authority or ‘superior wisdom’ on moral matters” (82). Every one of them, with a single exception, in fact includes an explanation of what separates the two endeavors—describing human morality on the one hand, and prescribing values or behaviors on the other—in the very books Shaw professes to find so alarming. The lone exception, Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, author of Just Babies: The Origins of Good and Evil, wrote to Haidt and Pinker, “The fact that one cannot derive morality from psychological research is so screamingly obvious that I never thought to explicitly write it down” (82).

Yet Shaw insists all of these authors commit the fallacy of moving from is to ought; you have to wonder if she even read the books she’s supposed to be reviewing—beyond mining them for damning quotes anyway. And didn’t any of the editors at The New York Review think to check some of her basic claims? Or were they simply hoping to bank on the publication of what amounts to controversy porn? (Think of the dilemma faced by the authors: do you respond and draw more attention to the piece, or do you ignore it and let some portion of the readership come away with a wildly mistaken impression?)

Haidt and Pinker do a fine job of calling out most of Shaw’s biggest mistakes and mischaracterizations. But I want to draw attention to two more instances of her falling short of any reasonable standard of scholarship, because each one reveals something important about the beliefs Shaw uses as her own moral compass. The authors under review situate their findings on human morality in a larger framework of theories about human evolution. Shaw characterizes this framework as “an unverifiable and unfalsifiable story about evolutionary psychology” (38). Shaw has evidently attended the Ken Ham school of evolutionary biology, which preaches that science can only concern itself with phenomena occurring right before our eyes in a lab. The reality is that, while testing adaptationist theories is a complicated endeavor, there are usually at least two ways to falsify them. You can show that the trait or behavior in question is absent in many cultures, or you can show that it emerges late in life after some sort of deliberate training. One of the books Shaw is supposedly reviewing, Bloom’s Just Babies, focuses specifically on research demonstrating that many of our common moral intuitions emerge when we’re babies, in our first year of life, with no deliberate training whatsoever.

Bloom comes in for some more targeted, if off-hand, criticism near the conclusion of Shaw’s essay for an article he wrote to challenge the increasingly popular sentiment that we can solve our problems as a society by encouraging everyone to be more empathetic. Empathy, Bloom points out, is a finite resource; we’re simply not capable of feeling for every single one of the millions of individuals in need of care throughout the world. So we need to offer that care based on principle, not feeling. Shaw avoids any discussion of her own beliefs about morality in her essay, but from the nature of her mischaracterization of Bloom’s argument we can start to get a sense of the ideology informing her prejudices. She insists that when Paul Bloom, in his own Atlantic article, “The Dark Side of Empathy,” warns us that empathy for people who are seen as victims may be associated with violent, punitive tendencies toward those in authority, we should be wary of extrapolating from his psychological claims a prescription for what should and should not be valued, or inferring that we need a moral corrective to a culture suffering from a supposed excess of empathic feelings. (40-1)

The “supposed excess of empathic feelings” isn’t the only laughable distortion people who actually read Bloom’s essay will catch out; the actual examples he cites of when empathy for victims leads to “violent, punitive tendencies” include Donald Trump and Ann Coulter stoking outrage against undocumented immigrants by telling stories of the crimes a few of them commit. This misrepresentation raises an important question: why would Shaw want to mislead her readers into believing Bloom’s intention is to protect those in authority? This brings us to the McCathyesque part of Shaw’s attack ad.

The sections of the essay drawing a web of guilt connecting the two psychologists who helped develop torture methods for the CIA to all the authors she’d have us believe are complicit focus mainly on Martin Seligman, whose theory of learned helplessness formed the basis of the CIA’s approach to harsh interrogation. Seligman is the founder of a subfield called Positive Psychology, which he developed as a counterbalance to what he perceived as an almost exclusive focus on all that can go wrong with human thinking, feeling, and behaving. His Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania has received $31 million in recent years from the Department of Defense—a smoking gun by Shaw’s lights. And Seligman even admits that on several occasions he met with those two psychologists who participated in the torture program. The other authors Shaw writes about have in turn worked with Seligman on a variety of projects. Haidt even wrote a book on Positive Psychology called The Happiness Hypothesis.

In Shaw’s view, learned helplessness theory is a potentially dangerous tool being wielded by a bunch of mad scientists and government officials corrupted by financial incentives and a lust for military dominance. To her mind, the notion that Seligman could simply want to help soldiers cope with the stresses of combat is all but impossible to even entertain. In this and every other instance when Shaw attempts to mislead her readers, it’s to put the same sort of negative spin on the psychologists’ explicitly stated positions. If Bloom says empathy has a dark side, then all the authors in question are against empathy. If Haidt argues that resilience—the flipside of learned helplessness—is needed to counteract a culture of victimhood, then all of these authors are against efforts to combat sexism and racism on college campuses. And, as we’ve seen, if these authors say we should question our moral intuitions, it’s because they want to be able to get away with crimes like torture. “Expertise in teaching people to override their moral intuitions is only a moral good if it serves good ends,” Shaw herself writes. “Those ends,” she goes on, “should be determined by rigorous moral deliberation” (40). Since this is precisely what the authors she’s criticizing say in their books, we’re left wondering what her real problem with them might be.

In her reply to Haidt and Pinker’s letter, Shaw suggests her aim for the essay was to encourage people to more closely scrutinize the “doctrines of Positive Psychology” and the central principles underlying psychological theories about human morality. I was curious to see how she’d respond to being called out for mistakenly stating that the psychologists were claiming moral authority and that they were given to using their research to defend the use of torture. Her main response is to repeat the central aspects of her rather flimsy case against Seligman. But then she does something truly remarkable; she doesn’t deny using guilt by imaginability—she defends it.