THE STORYTELLING APE

Essays and Book Reviews on Evolutionary Psychology, Anthropology, the Literature of Science and the Science of Literature

Kara and her older sister Crystal plan to leave a message in an abandoned house to prove they have more courage than Gloria, their rival at school. But Crystal does something weird before they ever arrive, and once they finally make it inside, the mysteries only deepen.

For anyone viewing his career through the lens of the currently ascendant “intersectional” ideology, McEwan’s ongoing success must stand as an annoying provocation—but it is McEwan himself who poses the real problem. What McEwan understands, though, is that fiction is the only realm where we enjoy the freedom to exchange our real identities for any of our choosing. He’s keenly aware of how much easier harsh truths are to take from moribund, wheelchair-bound old feminists than from comfortable old white men married to reason and realism.

As Graeber and Wengrow glibly generalize about the state of scholarship in their fields, only to turn around and poke holes in their semi-fictional accounts, you start to feel like you’ve been buttonholed by an old man at a bar as he tells a series of tendentious stories about how he bested impossibly dense adversaries in battles of wit. Indeed, the overarching problem with The Dawn of Everything is that it consists primarily of a long rant against the straw man of lockstep societal progression through rigid stages.

A group of friends gathers close to Halloween for their annual tradition of sharing ghost stories. For the past handful of years, they’ve also been inviting guests to tell new tales, chosen from among people who email the author. This year, an understated storyteller relates his experiences with a creepy space in the warehouse where he works and a search for a mysterious book that ensues.

Why would a public intellectual of Timothy Snyder’s stature accept the commission to review a book he couldn’t bring himself to read, only to go on to write a review that’s so caustic, contemptuous, careless, and dishonest that anyone who gets around to picking up Jonathan Gottschall’s book will see at a glance that the reviewer is sanctimonious, superior, mean-spirited, and completely full of shit? Something interesting must be happening behind the scenes to make Snyder so reckless with his reputation for honest scholarship, something urgent enough to overshadow any concern for his integrity. What might that something be?

Hilary Mantel won a Booker Prize for each of the first two installments of her Cromwell Trilogy. Is the third and final book, “The Mirror and the Light,” a fit successor? Critic Daniel Mendelsohn doesn’t think so, insisting the story lacks a strong central theme around which the profusion of historical episodes could cohere. But it just may be that he was looking for that unifying theme in the wrong place.

Sam Harris’s instruction to turn attention back on itself, to “look for the looker,” is already confusing and frustrating enough. Then he tells us to do it in the space of time it takes him to snap his fingers. How are you supposed to look for the looker when your eyes are closed and pointed forward? And what exactly does he mean by “the looker” anyway? What are we supposed to be looking for? Well, the looker is the sense that we’re directing our attention from somewhere. And here I’ll explain how to look for that sense.

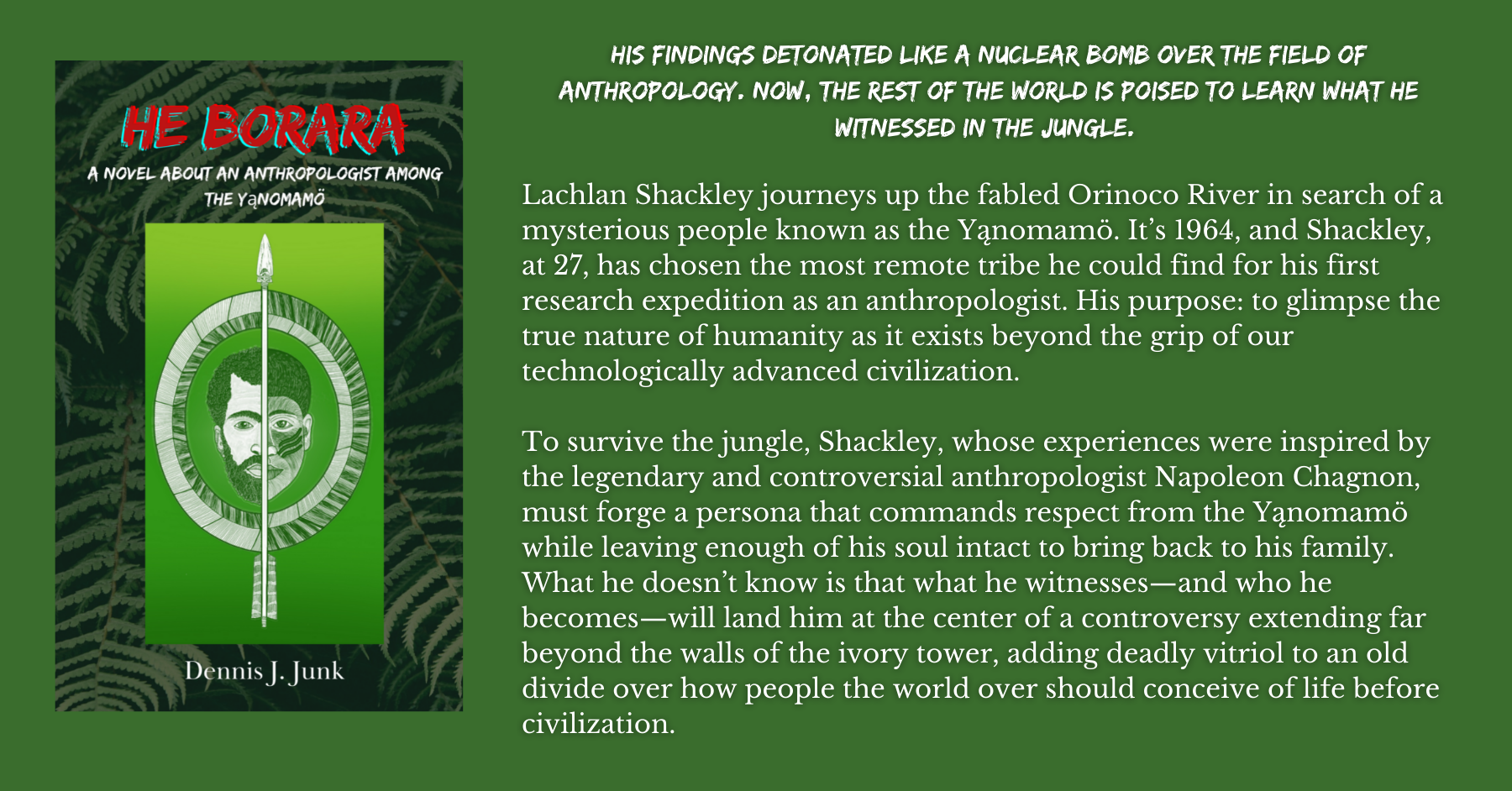

I put together a list of terms and definitions while writing my novel about an anthropologist studying the Yąnomamö. Good for students or researchers, or anyone else looking to learn some basic terms of the language. These definitions are mostly my own paraphrasing of Napoleon Chagnon’s.

The group of friends is back together for another round of Halloween stories, but this time they have a featured guest. Ken’s daughter Leena has been having conversations with a mysterious imaginary character named Piltok, along with several other fanciful creatures, all with disconcertingly short lifespans. So, Ken has come to share his story and get everyone’s reactions. What none of them knows is that the situation is about to get still more frightening.

Reviewing Steven Pinker’s book Rationality for Slate, McCormick takes issue with a small handful of examples of irrationality because the perpetrators are on the left side of the political divide. He argues that Pinker’s true purpose is to promote his own political agenda. But McCormick’s examples have some issues of their own.

Anthropologists Brian Ferguson and Douglas Fry can be counted on to pour cold water on any researcher’s claims about violence in human evolutionary history. But both have explained part of their motivation is to push back against a culture that believes violence is part of human nature. What does it mean to have such a nonscientific agenda in a what’s supposed to be a scientific debate?

The anthropologist Agustin Fuentes recently published an editorial in the journal Science to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of The Descent of Man by Charles Darwin. What did Fuentes see fit to say about the great man of science and his still controversial but undoubtedly brilliant work? Well, it turns out some parts of the book are less than charitable to people who aren’t of European descent. Some of the things Darwin wrote about women are pretty awful too. What are we to make of this?

What does Sam Harris mean when he says look for the looker? What does it mean to look for the seat of consciousness? Many users of the Waking Up app get frustrated by this instruction. Here’s a way of understanding the instruction I think is more helpful.

A follow up to last year’s “Cannonball,” “Jax” features another Halloween party with a group of young friends sharing their stories about the supernatural. This time, one of their fathers attends and tells the story of a dog under the mysterious sway of his former master.

The political discourse in this country has been taken over by the extremes on both sides. People in the middle get attacked from those on both of the poles. But centrists are the ones whose voices we need to hear now more than any others.

For six years now, our group of friends has been taking turns hosting these Halloween parties, and each year we gather around a fire—indoors this year—to share our experiences of the eerily unexplained. What made this year’s party different for me was that it was the first time my mom attended.

Your definition of a story in large part determines how you read it. Most kids in America are implicitly taught that stories are coded messages and that they should try to decipher what the author is trying to say—or what part of the status quo the author is endeavoring to perpetuate. But is that what a story really is? What alternative approaches are there to reading literature?

Is The Great Gatsby too heavy of a lift for high schoolers? More broadly, does assigning books that are far beyond students’ comprehension foster a hatred for reading? If so, what’s the alternative.

Critics like John Gray don't like what Steven Pinker has to say in his book Enlightenment Now. Unfortunately, they have to pretend he said something entirely different to effectively refute his arguments.

Origin myth of the Yanomamo. Sample chapter of “He Borara: a Novel about an Anthropologist among the Yąnomamö.”

Upon first reading Shaw’s piece, I dismissed it as a particularly unscrupulous bit of interdepartmental tribalism—a philosopher bemoaning the encroachment by pesky upstart scientists into what was formerly the bailiwick of philosophers. But then a line in Shaw’s attempted rebuttal of Haidt and Pinker’s letter sent me back to the original essay, and this time around I recognized it as a manifestation of a more widespread trend among scholars, and a rather unscholarly one at that.

For the modern reader, it may be a shock to learn about an early scientific explorer who wasn’t given to discounting the humanity of anyone whose ancestors weren’t European, having instead imagined some wandering sadist performing experiments with arcane instruments resembling miniaturized medieval torture devices, cutting and poking whatever parts and appendages got in the way of fitting all of humankind neatly into the racial hierarchy. Humboldt was instead such a devotee of Enlightenment principles that he felt the failure of The French Revolution to establish a lasting republic and the persistence of slavery in the U.S. as crushing disappointments all throughout the latter part of his life.

“Now I’m a grown man and I’ve never been big on all that Halloween, haunted-house type of shit. But in all of my adult life I’ve never felt the kind of—I don’t even know what to call it. It wasn’t fear, not like the kind you feel when you almost get into an accident in your car, or when you think you’re about to get jumped coming out of a bar. It was a completely different kind of fear, like you’re in the presence of something that’s just not right.”

Four or five casual arrangements don’t add up to one profound connection. Doing it that way is fun as hell, don’t get me wrong. But after a while it starts to feel shallow. You start to feel empty. Any one of the women I’m dating now could decide she wants something more serious with some other guy. That wouldn’t bother me. I’d be like, ‘Cool, I hope it works out for you. It was fun hanging out.’ But the fact that I can walk away like that shows how little meaning it ultimately has.

Three grown-ass men investigate strange happenings at the building where they all work. It’s a great Fort Wayne ghost story, one of many.

Robert Borofsky and his cadre of postmodernist activists try desperately to resuscitate the case against scientific anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon after disgraced pseudo-journalist Brian Tierney’s book “Darkness in El Dorado” is exposed as a work of fraud. The product is something only an ideologue can appreciate.

What has always made Sacks’s books so wonderfully engrossing, and what makes Sacks himself such a treasure, is his dual identity as a profoundly compassionate doctor and a consummate artist, one in constant search of the ideal form to convey his stories. His essays and books aren’t just cogent explorations of scientific mysteries; they consistently achieve the status of true literature. And now, with On the Move, Sacks has bequeathed to us a masterpiece of the autobiographical form.

Take a stand with me against hipster abuse!

This is a farcical take on some of the brainless criticisms you see of entertainment and pop culture from ideologues and hactavists who’ve convinced themselves they’re heroes for causes they’re really doing nothing to further.

Too often, we’re convinced by the passion with which someone expresses an idea—and that’s why there’s so much outrage in the news and in other media. Sam Harris has had a particularly hard time combatting outrage with cogent arguments, because he’s no sooner expressed an idea than his interlocutor is aggressively misinterpreting it.

The medievalist letter writer claims that being “part of the center” is what makes living in the enlightened West preferable to living in the 12th century. But there’s simply no way whoever wrote the letter actually believes this. If you happen to be poor, female, a racial or religious minority, a homosexual, or a member of any other marginalized group, you’d be far more loath to return to the Middle Ages than those of us comfortably ensconced in this notional center, just as you’d be loath to relocate to any society not governed by Enlightenment principles today.

This theme of compromised morality woven together with the mystery of language’s transformative ties to the world may suggest to some that the power of Bring up the Bodies comes from some embedded lesson about our imperiled integrity or lost humanity. But it’s a mistake to treat a narrative solely, or even predominantly, as a matter of meaning. “A statute is written to entrap meaning,” as Cromwell reasons, “a poem to escape it.”

Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall” is one of the most successful novels of the 21st century. It’s spawned sequels, stage productions, even a miniseries. But much of the novel’s genius lies in its line-by-line brilliance. Read more to get a better sense of what “Wolf Hall” is really about and how it has enthralled so many readers.

Far too many literature teachers encourage us to treat great works like coded messages with potentially harmful effects on society. Thus, many of us were taught we needed to resist being absorbed by a story and enchanted by language—but aren’t those the two parts of reading we’re most excited about enjoying?

A dear friend takes the opportunity to satirically poke some fun at me, while at the same time expressing a tad bit of admiration.

In my first foray into Sam Harris’s work, I struggle with some of the concepts he holds up as keys to a more contented, more spiritual life. Along the way, though, I find myself captivated by the details of Harris’s own spiritual journey, and I’m left wondering if there just may be more to this meditation stuff than I’m able to initially wrap my mind around.

Authors often serve as mental models helping readers imagine protagonists. This can be disconcerting when the protagonist engage in unsavory behavior. Is Stephen King as scary as his characters? Probably not, we all know, but the workings of his imagination are enough to make us wonder just a bit.

Russell Arden contemplates leaving behind useless socialization so he can pursue his passions. When he finally decides to go through with it, he finds himself joining another society of sorts, the outcasts from the world of pretension and comfort. But where he expects to thrive he finds himself still longing for something he can’t identify.

Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer-winning novel “The Goldfinch” prompted critic James Wood to lament the demise of the more weighty and serious novels of the past and the rise of fantastical stories in a world where adults go around reading Harry Potter. But is Wood confused about what storytelling really is?

James Wood criticized Cormac McCathy’s “No Country for Old Men” for being too trapped by its own genre tropes. Wood has a strikingly keen eye for literary registers, but he’s missing something crucial in his analysis of McCarthy’s work. Rohan Wilson’s “The Roving Party” works on some of the same principles as McCarthy’s work, and it shows that the authors’ visions extend far beyond the pages of any book.

A reflection on time and friendship, the product of reading a bunch of Cormac McCarthy, going through a breakup, and going out west to visit some national parks with old friends.

Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” is a brilliantly witty and trenchant exploration of how identities shift and transform, both within relationships and as part of an ongoing struggle for each of us to master the plot of our own narratives.

Nicholas Wade went there. In his book “A Troublesome Inheritance,” he argues that not only is race a real, biological phenomenon, but one that has potentially important implications for our understanding of the fates of different peoples. Is it possible to even discuss such things without being justifiably labeled a racist? More importantly, if biological differences do show up in the research, how can we discuss them without being grossly immoral?

If you wanted to know how many young women are sexually assaulted on college campuses, you could easily devise a survey to ask a sample of them directly. But that’s not what advocates of stricter measures to prevent assault tend to do. Instead, they ask ambiguous questions they go on to interpret as suggesting an assault occurred. This almost guarantees wildly inflated numbers.

Rebecca Mead’s “My Life in Middlemarch,” about her lifelong love of George Eliot’s masterpiece, discusses various ways to think of the relationship between readers and authors, as well as the relationship between readers and characters. To get at the meat of these questions, though, you have to begin with an understanding of what literature is and how a piece of fiction works.

You may have noticed that the term sexism has come to refer to any suggestion that there may be meaningful differences between women and men, or between what’s considered feminine and what’s considered masculine. But is the denial of sex differences really what’s best for women? Is it what’s best for anyone.

Gender-flipped performances are often billed as experiments to help audiences reconsider and look more deeply into what we consider the essential characteristics of males and females. But not to far beneath the surface, you find that they tend to be more like ideological cudgels for those who would deny biological differences.

With “Neanderthal Man,” paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo has penned a deeply personal and sparely stylish paean to the field of paleogenetics and all the colleagues and supporters who helped him create it. The book offers an invaluable look behind the scenes of some of the most fascinating research in recent decades.

The pages of Ruth Ozeki’s novel A Tale for the Time Being are brimful with the joys and heartache, not just of fiction in general, but of literary fiction in particular, with the bite of reality that sinks deeper than that of the commercial variety, which sacrifices lasting impact for immediate thrills—this despite the Gothic and science fiction elements Ozeki judiciously sprinkles throughout her chapters.

Joshua Greene’s book “Moral Tribes” posits a dual-system theory of morality, where a quick, intuitive system 1 makes judgments based on deontological considerations—”it’s just wrong—whereas the slower, more deliberative system 2 takes time to calculate the consequences of any given choice. Audiences can see these two systems on display in the series “Breaking Bad,” as well as in critics’ and audiences’ responses.

Kara and her older sister Crystal plan to leave a message in an abandoned house to prove they have more courage than Gloria, their rival at school. But Crystal does something weird before they ever arrive, and once they finally make it inside, the mysteries only deepen.