READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Napoleon Chagnon's Crucible and the Ongoing Epidemic of Moralizing Hysteria in Academia

Napoleon Chagnon was targeted by postmodern activists and anthropologists, who trumped up charges against him and hoped to sacrifice his reputation on the altar of social justice. In retrospect, his case looks like an early warning sign of what would come to be called “cancel culture.” Fortunately, Chagnon was no pushover, and there were a lot of people who saw through the lies being spread about him. “Noble Savages” is in a part a great adventure story and in part his response to the tragic degradation of the field of anthropology as it succumbs to the lures of ideology.

When Arthur Miller adapted the script of The Crucible, his play about the Salem Witch Trials originally written in 1953, for the 1996 film version, he enjoyed additional freedom to work with the up-close visual dimensions of the tragedy. In one added scene, the elderly and frail George Jacobs, whom we first saw lifting one of his two walking sticks to wave an unsteady greeting to a neighbor, sits before a row of assembled judges as the young Ruth Putnam stands accusing him of assaulting her. The girl, ostensibly shaken from the encounter and frightened lest some further terror ensue, dramatically recounts her ordeal, saying,

He come through my window and then he lay down upon me. I could not take breath. His body crush heavy upon me, and he say in my ear, “Ruth Putnam, I will have your life if you testify against me in court.”

This quote she delivers in a creaky imitation of the old man’s voice. When one of the judges asks Jacobs what he has to say about the charges, he responds with the glaringly obvious objection: “But, your Honor, I must have these sticks to walk with—how may I come through a window?” The problem with this defense, Jacobs comes to discover, is that the judges believe a person can be in one place physically and in another in spirit. This poor tottering old man has no defense against so-called “spectral evidence.” Indeed, as judges in Massachusetts realized the year after Jacobs was hanged, no one really has any defense against spectral evidence. That’s part of the reason why it was deemed inadmissible in their courts, and immediately thereafter convictions for the crime of witchcraft ceased entirely.

Many anthropologists point to the low cost of making accusations as a factor in the evolution of moral behavior. People in small societies like the ones our ancestors lived in for millennia, composed of thirty or forty profoundly interdependent individuals, would have had to balance any payoff that might come from immoral deeds against the detrimental effects to their reputations of having those deeds discovered and word of them spread. As the generations turned over and over again, human nature adapted in response to the social enforcement of cooperative norms, and individuals came to experience what we now recognize as our moral emotions—guilt which is often preëmptive and prohibitive, shame, indignation, outrage, along with the more positive feelings associated with empathy, compassion, and loyalty.

The legacy of this process of reputational selection persists in our prurient fascination with the misdeeds of others and our frenzied, often sadistic, delectation in the spreading of salacious rumors. What Miller so brilliantly dramatizes in his play is the irony that our compulsion to point fingers, which once created and enforced cohesion in groups of selfless individuals, can in some environments serve as a vehicle for our most viciously selfish and inhuman impulses. This is why it is crucial that any accusation, if we as a society are to take it at all seriously, must provide the accused with some reliable means of acquittal. Charges that can neither be proven nor disproven must be seen as meaningless—and should even be counted as strikes against the reputation of the one who levels them.

While this principle runs into serious complications in situations with crimes that are as inherently difficult to prove as they are horrific, a simple rule proscribing any glib application of morally charged labels is a crucial yet all-too-popularly overlooked safeguard against unjust calumny. In this age of viral dissemination, the rapidity with which rumors spread coupled with the absence of any reliable assurances of the validity of messages bearing on the reputations of our fellow citizens demand that we deliberately work to establish as cultural norms the holding to account of those who make accusations based on insufficient, misleading, or spectral evidence—and the holding to account as well, to only a somewhat lesser degree, of those who help propagate rumors without doing due diligence in assessing their credibility.

The commentary attending the publication of anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon’s memoir of his research with the Yanomamö tribespeople in Venezuela calls to mind the insidious “Teach the Controversy” PR campaign spearheaded by intelligent design creationists. Coming out against the argument that students should be made aware of competing views on the value of intelligent design inevitably gives the impression of close-mindedness or dogmatism. But only a handful of actual scientists have any truck with intelligent design, a dressed-up rehashing of the old God-of-the-Gaps argument based on the logical fallacy of appealing to ignorance—and that ignorance, it so happens, is grossly exaggerated.

Teaching the controversy would therefore falsely imply epistemological equivalence between scientific views on evolution and those that are not-so-subtly religious. Likewise, in the wake of allegations against Chagnon about mistreatment of the people whose culture he made a career of studying, many science journalists and many of his fellow anthropologists still seem reluctant to stand up for him because they fear doing so would make them appear insensitive to the rights and concerns of indigenous peoples. Instead, they take refuge in what they hope will appear a balanced position, even though the evidence on which the accusations rested has proven to be entirely spectral.

Chagnon’s Noble Savages: My Life among Two Dangerous Tribes—the Yanomamö and the Anthropologists is destined to be one of those books that garners commentary by legions of outspoken scholars and impassioned activists who never find the time to actually read it. Science writer John Horgan, for instance, has published two blog posts on Chagnon in recent weeks, and neither of them features a single quote from the book. In the first, he boasts of his resistance to bullying, via email, by five prominent sociobiologists who had caught wind of his assignment to review Patrick Tierney’s book Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon and insisted that he condemn the work and discourage anyone from reading it. Against this pressure, Horgan wrote a positive review in which he repeats several horrific accusations that Tierney makes in the book before going on to acknowledge that the author should have worked harder to provide evidence of the wrongdoings he reports on.

But Tierney went on to become an advocate for Indian rights. And his book’s faults are outweighed by its mass of vivid, damning detail. My guess is that it will become a classic in anthropological literature, sparking countless debates over the ethics and epistemology of field studies.

Horgan probably couldn’t have known at the time (though those five scientists tried to warn him) that giving Tierney credit for prompting debates about Indian rights and ethnographic research methods was a bit like praising Abigail Williams, the original source of accusations of witchcraft in Salem, for sparking discussions about child abuse. But that he stands by his endorsement today, saying,

“I have one major regret concerning my review: I should have noted that Chagnon is a much more subtle theorist of human nature than Tierney and other critics have suggested,” as balanced as that sounds, casts serious doubt on his scholarship, not to mention his judgment.

What did Tierney falsely accuse Chagnon of? There are over a hundred specific accusations in the book (Chagnon says his friend William Irons flagged 106 [446]), but the most heinous whopper comes in the fifth chapter, titled “Outbreak.” In 1968, Chagnon was helping the geneticist James V. Neel collect blood samples from the Yanomamö—in exchange for machetes—so their DNA could be compared with that of people in industrialized societies. While they were in the middle of this project, a measles epidemic broke out, and Neel had discovered through earlier research that the Indians lacked immunity to this disease, so the team immediately began trying to reach all of the Yanomamö villages to vaccinate everyone before the contagion reached them. Most people who knew about the episode considered what the scientists did heroic (and several investigations now support this view). But Tierney, by creating the appearance of pulling together multiple threads of evidence, weaves together a much different story in which Neel and Chagnon are cast as villains instead of heroes. (The version of the book I’ll quote here is somewhat incoherent because it went through some revisions in attempts to deal with holes in the evidence that were already emerging pre-publication.)

First, Tierney misinterprets some passages from Neel’s books as implying an espousal of eugenic beliefs about the Indians, namely that by remaining closer to nature and thus subject to ongoing natural selection they retain all-around superior health, including better immunity. Next, Tierney suggests that the vaccine Neel chose, Edmonston B, which is usually administered with a drug called gamma globulin to minimize reactions like fevers, is so similar to the measles virus that in the immune-suppressed Indians it actually ended up causing a suite of symptoms that was indistinguishable from full-blown measles. The implication is clear. Tierney writes,

Chagnon and Neel described an effort to “get ahead” of the measles epidemic by vaccinating a ring around it. As I have reconstructed it, the 1968 outbreak had a single trunk, starting at the Ocamo mission and moving up the Orinoco with the vaccinators. Hundreds of Yanomami died in 1968 on the Ocamo River alone. At the time, over three thousand Yanomami lived on the Ocamo headwaters; today there are fewer than two hundred. (69)

At points throughout the chapter, Tierney seems to be backing off the worst of his accusations; he writes, “Neel had no reason to think Edmonston B could become transmissible. The outbreak took him by surprise.” But even in this scenario Tierney suggests serious wrongdoing: “Still, he wanted to collect data even in the midst of a disaster” (82).

Earlier in the chapter, though, Tierney makes a much more serious charge. Pointing to a time when Chagnon showed up at a Catholic mission after having depleted his stores of gamma globulin and nearly run out of Edmonston B, Tierney suggests the shortage of drugs was part of a deliberate plan. “There were only two possibilities,” he writes,

Either Chagnon entered the field with only forty doses of virus; or he had more than forty doses. If he had more than forty, he deliberately withheld them while measles spread for fifteen days. If he came to the field with only forty doses, it was to collect data on a small sample of Indians who were meant to receive the vaccine without gamma globulin. Ocamo was a good choice because the nuns could look after the sick while Chagnon went on with his demanding work. Dividing villages into two groups, one serving as a control, was common in experiments and also a normal safety precaution in the absence of an outbreak. (60)

Thus Tierney implies that Chagnon was helping Neel test his eugenics theory and in the process became complicit in causing an epidemic, maybe deliberately, that killed hundreds of people. Tierney claims he isn’t sure how much Chagnon knew about the experiment; he concedes at one point that “Chagnon showed genuine concern for the Yanomami,” before adding, “At the same time, he moved quickly toward a cover-up” (75).

Near the end of his “Outbreak” chapter, Tierney reports on a conversation with Mark Papania, a measles expert at the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta. After running his hypothesis about how Neel and Chagnon caused the epidemic with the Edmonston B vaccine by Papania, Tierney claims he responded, “Sure, it’s possible.” He goes on to say that while Papania informed him there were no documented cases of the vaccine becoming contagious he also admitted that no studies of adequate sensitivity had been done. “I guess we didn’t look very hard,” Tierney has him saying (80). But evolutionary psychologist John Tooby got a much different answer when he called Papania himself. In a an article published on Slate—nearly three weeks before Horgan published his review, incidentally—Tooby writes that the epidemiologist had a very different attitude to the adequacy of past safety tests from the one Tierney reported:

it turns out that researchers who test vaccines for safety have never been able to document, in hundreds of millions of uses, a single case of a live-virus measles vaccine leading to contagious transmission from one human to another—this despite their strenuous efforts to detect such a thing. If attenuated live virus does not jump from person to person, it cannot cause an epidemic. Nor can it be planned to cause an epidemic, as alleged in this case, if it never has caused one before.

Tierney also cites Samuel Katz, the pediatrician who developed Edmonston B, at a few points in the chapter to support his case. But Katz responded to requests from the press to comment on Tierney’s scenario by saying,

the use of Edmonston B vaccine in an attempt to halt an epidemic was a justifiable, proven and valid approach. In no way could it initiate or exacerbate an epidemic. Continued circulation of these charges is not only unwarranted, but truly egregious.

Tooby included a link to Katz’s response, along with a report from science historian Susan Lindee of her investigation of Neel’s documents disproving many of Tierney’s points. It seems Horgan should’ve paid a bit more attention to those emails he was receiving.

Further investigations have shown that pretty much every aspect of Tierney’s characterization of Neel’s beliefs and research agenda was completely wrong. The report from a task force investigation by the American Society of Human Genetics gives a sense of how Tierney, while giving the impression of having conducted meticulous research, was in fact perpetrating fraud. The report states,

Tierney further suggests that Neel, having recognized that the vaccine was the cause of the epidemic, engineered a cover-up. This is based on Tierney’s analysis of audiotapes made at the time. We have reexamined these tapes and provide evidence to show that Tierney created a false impression by juxtaposing three distinct conversations recorded on two separate tapes and in different locations. Finally, Tierney alleges, on the basis of specific taped discussions, that Neel callously and unethically placed the scientific goals of the expedition above the humanitarian need to attend to the sick. This again is shown to be a complete misrepresentation, by examination of the relevant audiotapes as well as evidence from a variety of sources, including members of the 1968 expedition.

This report was published a couple years after Tierney’s book hit the shelves. But there was sufficient evidence available to anyone willing to do the due diligence in checking out the credibility of the author and his claims to warrant suspicion that the book’s ability to make it onto the shortlist for the National Book Award is indicative of a larger problem.

*******

With the benefit of hindsight and a perspective from outside the debate (though I’ve been following the sociobiology controversy for a decade and a half, I wasn’t aware of Chagnon’s longstanding and personal battles with other anthropologists until after Tierney’s book was published) it seems to me that once Tierney had been caught misrepresenting the evidence in support of such an atrocious accusation his book should have been removed from the shelves, and all his reporting should have been dismissed entirely. Tierney himself should have been made to answer for his offense. But for some reason none of this happened.

The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, for instance, to whom Chagnon has been a bête noire for decades, brushed off any concern for Tierney’s credibility in his review of Darkness in El Dorado, published a full month after Horgan’s, apparently because he couldn’t resist the opportunity to write about how much he hates his celebrated colleague. Sahlins’s review is titled “Guilty not as Charged,” which is already enough to cast doubt on his capacity for fairness or rationality. Here’s how he sums up the issue of Tierney’s discredited accusation in relation to the rest of the book:

The Kurtzian narrative of how Chagnon achieved the political status of a monster in Amazonia and a hero in academia is truly the heart of Darkness in El Dorado. While some of Tierney’s reporting has come under fire, this is nonetheless a revealing book, with a cautionary message that extends well beyond the field of anthropology. It reads like an allegory of American power and culture since Vietnam.

Sahlins apparently hasn’t read Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness or he’d know Chagnon is no Kurtz. And Vietnam? The next paragraph goes into more detail about this “allegory,” as if Sahlins’s conscripting of him into service as a symbol of evil somehow establishes his culpability. To get an idea of how much Chagnon actually had to do with Vietnam, we can look at a passage early in Noble Savages about how disconnected from the outside world he was while doing his field work:

I was vaguely aware when I went into the Yanomamö area in late 1964 that the United States had sent several hundred military advisors to South Vietnam to help train the South Vietnamese army. When I returned to Ann Arbor in 1966 the United States had some two hundred thousand combat troops there. (36)

But Sahlins’s review, as bizarre as it is, is important because it’s representative of the types of arguments Chagnon’s fiercest anthropological critics make against his methods, his theories, but mainly against him personally. In another recent comment on how “The Napoleon Chagnon Wars Flare Up Again,” Barbara J. King betrays a disconcerting and unscholarly complacence with quoting other, rival anthropologists’ words as evidence of Chagnon’s own thinking. Alas, King too is weighing in on the flare-up without having read the book, or anything else by the author it seems. And she’s also at pains to appear fair and balanced, even though the sources she cites against Chagnon are neither, nor are they the least bit scientific. Of Sahlins’s review of Darkness in El Dorado, she writes,

The Sahlins essay from 2000 shows how key parts of Chagnon’s argument have been “dismembered” scientifically. In a major paper published in 1988, Sahlins says, Chagnon left out too many relevant factors that bear on Ya̧nomamö males’ reproductive success to allow any convincing case for a genetic underpinning of violence.

It’s a bit sad that King feels it’s okay to post on a site as popular as NPR and quote a criticism of a study she clearly hasn’t read—she could have downloaded the pdf of Chagnon’s landmark paper “Life Histories, Blood Revenge, and Warfare in a Tribal Population,” for free. Did Chagnon claim in the study that it proved violence had a genetic underpinning? It’s difficult to tell what the phrase “genetic underpinning” even means in this context.

To lend further support to Sahlins’s case, King selectively quotes another anthropologist, Jonathan Marks. The lines come from a rant on his blog (I urge you to check it out for yourself if you’re at all suspicious about the aptness of the term rant to describe the post) about a supposed takeover of anthropology by genetic determinism. But King leaves off the really interesting sentence at the end of the remark. Here’s the whole passage explaining why Marks thinks Chagnon is an incompetent scientist:

Let me be clear about my use of the word “incompetent”. His methods for collecting, analyzing and interpreting his data are outside the range of acceptable anthropological practices. Yes, he saw the Yanomamo doing nasty things. But when he concluded from his observations that the Yanomamo are innately and primordially “fierce” he lost his anthropological credibility, because he had not demonstrated any such thing. He has a right to his views, as creationists and racists have a right to theirs, but the evidence does not support the conclusion, which makes it scientifically incompetent.

What Marks is saying here is not that he has evidence of Chagnon doing poor field work; rather, Marks dismisses Chagnon merely because of his sociobiological leanings. Note too that the italicized words in the passage are not quotes. This is important because along with the false equation of sociobiology with genetic determinism this type of straw man underlies nearly all of the attacks on Chagnon. Finally, notice how Marks slips into the realm of morality as he tries to traduce Chagnon’s scientific credibility. In case you think the link with creationism and racism is a simple analogy—like the one I used myself at the beginning of this essay—look at how Marks ends his rant:

So on one side you’ve got the creationists, racists, genetic determinists, the Republican governor of Florida, Jared Diamond, and Napoleon Chagnon–and on the other side, you’ve got normative anthropology, and the mother of the President. Which side are you on?

How can we take this at all seriously? And why did King misleadingly quote, on a prominent news site, such a seemingly level-headed criticism which in context reveals itself as anything but level-headed? I’ll risk another analogy here and point out that Marks’s comments about genetic determinism taking over anthropology are similar in both tone and intellectual sophistication to Glenn Beck’s comments about how socialism is taking over American politics.

King also links to a review of Noble Savages that was published in the New York Times in February, and this piece is even harsher to Chagnon. After repeating Tierney’s charge about Neel deliberately causing the 1968 measles epidemic and pointing out it was disproved, anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli writes of the American Anthropological Association investigation that,

The committee was split over whether Neel’s fervor for observing the “differential fitness of headmen and other members of the Yanomami population” through vaccine reactions constituted the use of the Yanomamö as a Tuskegee-like experimental population.

Since this allegation has been completely discredited by the American Society of Human Genetics, among others, Povinelli’s repetition of it is irresponsible, as was the Times failure to properly vet the facts in the article.

Try as I might to remain detached from either side as I continue to research this controversy (and I’ve never met any of these people), I have to say I found Povinelli’s review deeply offensive. The straw men she shamelessly erects and the quotes she shamelessly takes out of context, all in the service of an absurdly self-righteous and substanceless smear, allow no room whatsoever for anything answering to the name of compassion for a man who was falsely accused of complicity in an atrocity. And in her zeal to impugn Chagnon she propagates a colorful and repugnant insult of her own creation, which she misattributes to him. She writes,

Perhaps it’s politically correct to wonder whether the book would have benefited from opening with a serious reflection on the extensive suffering and substantial death toll among the Yanomamö in the wake of the measles outbreak, whether or not Chagnon bore any responsibility for it. Does their pain and grief matter less even if we believe, as he seems to, that they were brutal Neolithic remnants in a land that time forgot? For him, the “burly, naked, sweaty, hideous” Yanomamö stink and produce enormous amounts of “dark green snot.” They keep “vicious, underfed growling dogs,” engage in brutal “club fights” and—God forbid!—defecate in the bush. By the time the reader makes it to the sections on the Yanomamö’s political organization, migration patterns and sexual practices, the slant of the argument is evident: given their hideous society, understanding the real disaster that struck these people matters less than rehabilitating Chagnon’s soiled image.

In other words, Povinelli’s response to Chagnon’s “harrowing” ordeal, is to effectively say, Maybe you’re not guilty of genocide, but you’re still guilty for not quitting your anthropology job and becoming a forensic epidemiologist. Anyone who actually reads Noble Savages will see quite clearly the “slant” Povinelli describes, along with those caricatured “brutal Neolithic remnants,” must have flown in through her window right next to George Jacobs.

Povinelli does characterize one aspect of Noble Savages correctly when she complains about its “Manichean rhetorical structure,” with the bad Rousseauian, Marxist, postmodernist cultural anthropologists—along with the corrupt and PR-obsessed Catholic missionaries—on one side, and the good Hobbesian, Darwinian, scientific anthropologists on the other, though it’s really just the scientific part he’s concerned with. I actually expected to find a more complicated, less black-and-white debate taking place when I began looking into the attacks on Chagnon’s work—and on Chagnon himself. But what I ended up finding was that Chagnon’s description of the division, at least with regard to the anthropologists (I haven’t researched his claims about the missionaries) is spot-on, and Povinelli’s repulsive review is a case in point.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t legitimate scientific disagreements about sociobiology. In fact, Chagnon writes about how one of his heroes is “calling into question some of the most widely accepted views” as early as his dedication page, referring to E.O. Wilson’s latest book The Social Conquest of Earth. But what Sahlins, Marks, and Povinelli offer is neither legitimate nor scientific. These commenters really are, as Chagnon suggests, representative of a subset of cultural anthropologists completely given over to a moralizing hysteria. Their scholarship is as dishonest as it is defamatory, their reasoning rests on guilt by free-association and the tossing up and knocking down of the most egregious of straw men, and their tone creates the illusion of moral certainty coupled with a longsuffering exasperation with entrenched institutionalized evils. For these hysterical moralizers, it seems any theory of human behavior that involves evolution or biology represents the same kind of threat as witchcraft did to the people of Salem in the 1690s, or as communism did to McCarthyites in the 1950s. To combat this chimerical evil, the presumed righteous ends justify the deceitful means.

The unavoidable conclusion with regard to the question of why Darkness in El Dorado wasn’t dismissed outright when it should have been is that even though it has been established that Chagnon didn’t commit any of the crimes Tierney accused him of, as far as his critics are concerned, he may as well have. Somehow cultural anthropologists have come to occupy a bizarre culture of their own in which charging a colleague with genocide doesn’t seem like a big deal. Before Tierney’s book hit the shelves, two anthropologists, Terence Turner and Leslie Sponsel, co-wrote an email to the American Anthropological Association which was later sent to several journalists. Turner and Sponsel later claimed the message was simply a warning about the “impending scandal” that would result from the publication of Darkness in El Dorado. But the hyperbole and suggestive language make it read more like a publicity notice than a warning. “This nightmarish story—a real anthropological heart of darkness beyond the imagining of even a Josef Conrad (though not, perhaps, a Josef Mengele)”—is it too much to ask of those who are so fond of referencing Joseph Conrad that they actually read his book?—“will be seen (rightly in our view) by the public, as well as most anthropologists, as putting the whole discipline on trial.” As it turned out, though, the only one who was put on trial, by the American Anthropological Association—though officially it was only an “inquiry”—was Napoleon Chagnon.

Chagnon’s old academic rivals, many of whom claim their problem with him stems from the alleged devastating impact of his research on Indians, fail to appreciate the gravity of Tierney’s accusations. Their blasé response to the author being exposed as a fraud gives the impression that their eagerness to participate in the pile-on has little to do with any concern for the Yanomamö people. Instead, they embraced Darkness in El Dorado because it provided good talking points in the campaign against their dreaded nemesis Napoleon Chagnon. Sahlins, for instance, is strikingly cavalier about the personal effects of Tierney’s accusations in the review cited by King and Horgan:

The brouhaha in cyberspace seemed to help Chagnon’s reputation as much as Neel’s, for in the fallout from the latter’s defense many academics also took the opportunity to make tendentious arguments on Chagnon’s behalf. Against Tierney’s brief that Chagnon acted as an anthro-provocateur of certain conflicts among the Yanomami, one anthropologist solemnly demonstrated that warfare was endemic and prehistoric in the Amazon. Such feckless debate is the more remarkable because most of the criticisms of Chagnon rehearsed by Tierney have been circulating among anthropologists for years, and the best evidence for them can be found in Chagnon’s writings going back to the 1960s.

Sahlins goes on to offer his own sinister interpretation of Chagnon’s writings, using the same straw man and guilt-by-free-association techniques common to anthropologists in the grip of moralizing hysteria. But I can’t help wondering why anyone would take a word he says seriously after he suggests that being accused of causing a deadly epidemic helped Neel’s and Chagnon’s reputations.

*******

Marshall Sahlins recently made news by resigning from the National Academy of Sciences in protest against the organization’s election of Chagnon to its membership and its partnerships with the military. In explaining his resignation, Sahlins insists that Chagnon, based on the evidence of his own writings, did serious harm to the people whose culture he studied. Sahlins also complains that Chagnon’s sociobiological ideas about violence are so wrongheaded that they serve to “discredit the anthropological discipline.” To back up his objections, he refers interested parties to that same review of Darkness in El Dorado King links to on her post.

Though Sahlins explains his moral and intellectual objections separately, he seems to believe that theories of human behavior based on biology are inherently immoral, as if theorizing that violence has “genetic underpinnings” is no different from claiming that violence is inevitable and justifiable. This is why Sahlins can’t discuss Chagnon without reference to Vietnam. He writes in his review,

The ‘60s were the longest decade of the 20th century, and Vietnam was the longest war. In the West, the war prolonged itself in arrogant perceptions of the weaker peoples as instrumental means of the global projects of the stronger. In the human sciences, the war persists in an obsessive search for power in every nook and cranny of our society and history, and an equally strong postmodern urge to “deconstruct” it. For his part, Chagnon writes popular textbooks that describe his ethnography among the Yanomami in the 1960s in terms of gaining control over people.

Sahlins doesn’t provide any citations to back up this charge—he’s quite clearly not the least bit concerned with fairness or solid scholarship—and based on what Chagnon writes in Noble Savages this fantasy of “gaining control” originates in the mind of Sahlins, not in the writings of Chagnon.

For instance, Chagnon writes of being made the butt of an elaborate joke several Yanomamö conspired to play on him by giving him fake names for people in their village (like Hairy Cunt, Long Dong, and Asshole). When he mentions these names to people in a neighboring village, they think it’s hilarious. “My face flushed with embarrassment and anger as the word spread around the village and everybody was laughing hysterically.” And this was no minor setback: “I made this discovery some six months into my fieldwork!” (66) Contrary to the despicable caricature Povinelli provides as well, Chagnon writes admiringly of the Yanomamö’s “wicked humor,” and how “They enjoyed duping others, especially the unsuspecting and gullible anthropologist who lived among them” (67). Another gem comes from an episode in which he tries to treat a rather embarrassing fungal infection: “You can’t imagine the hilarious reaction of the Yanomamö watching the resident fieldworker in a most indescribable position trying to sprinkle foot powder onto his crotch, using gravity as a propellant” (143).

The bitterness, outrage, and outright hatred directed at Chagnon, alongside the overt nonexistence of evidence that he’s done anything wrong, seem completely insane until you consider that this preeminent anthropologist falls afoul of all the –isms that haunt the fantastical armchair obsessions of postmodern pseudo-scholars. Chagnon stands as a living symbol of the white colonizer exploiting indigenous people and resources (colonialism); he propagates theories that can be read as supportive of fantasies about individual and racial superiority (Social Darwinism, racism); he reports on tribal warfare and cruelty toward women, with the implication that these evils are encoded in our genes (neoconservativism, sexism, biological determinism). It should be clear that all of this is nonsense: any exploitation is merely alleged and likely outweighed by efforts at vaccination against diseases introduced by missionaries and gold miners; sociobiology doesn’t focus on racial differences, and superiority is a scientifically meaningless term; and the fact that genes play a role in some behavior implies neither that the behavior is moral nor that it is inevitable. The truly evil –ism at play in the campaign against Chagnon is postmodernism—an ideology which functions as little more than a factory for the production of false accusations.

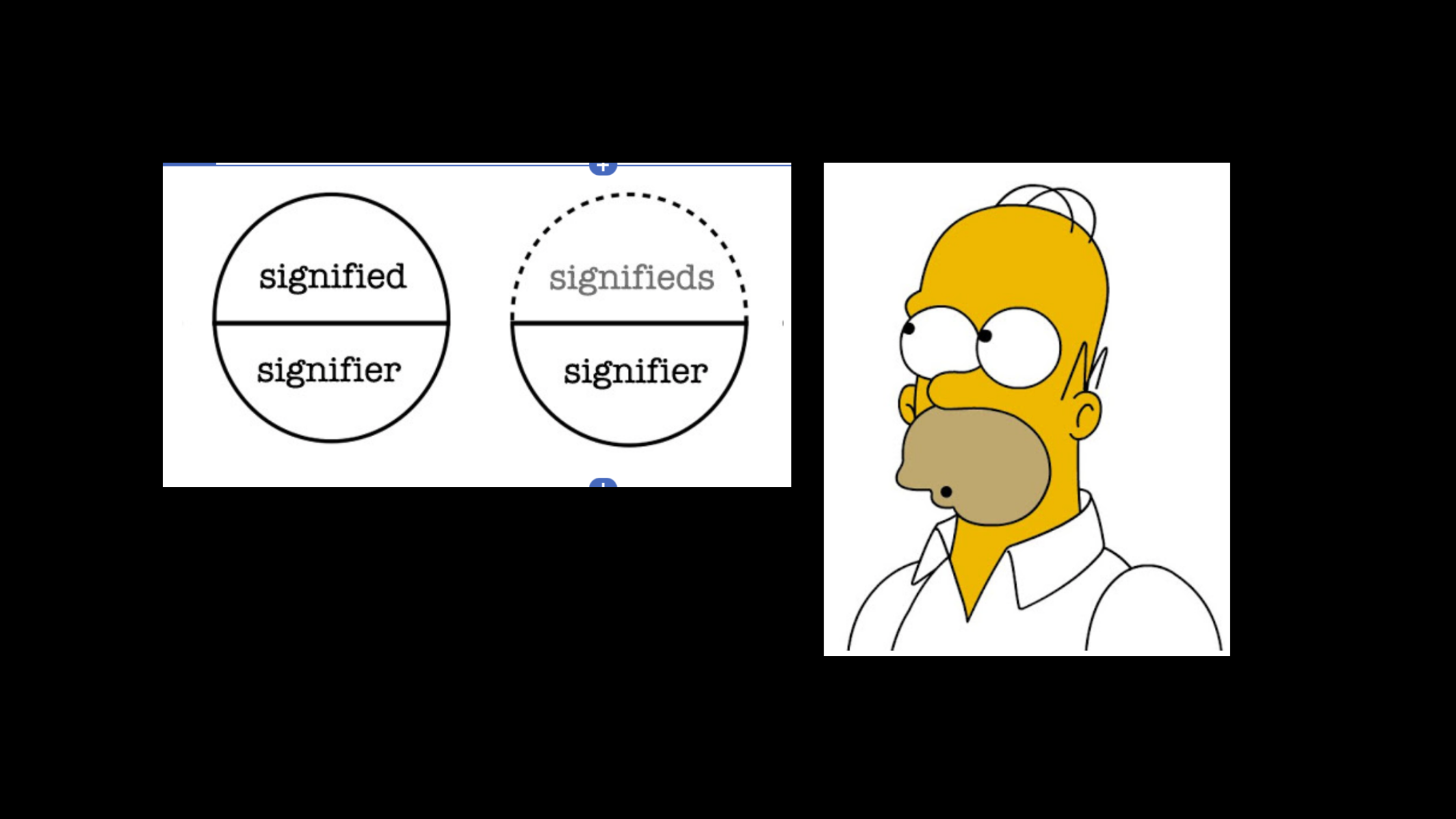

There are two main straw men that are bound to be rolled out by postmodern critics of evolutionary theories of behavior in any discussion of morally charged topics. The first is the gene-for misconception.

Every anthropologist, sociobiologist, and evolutionary psychologist knows that there is no gene for violence and warfare in the sense that would mean everyone born with a particular allele will inevitably grow up to be physically aggressive. Yet, in any discussion of the causes of violence, or any other issue in which biology is implicated, critics fall all over themselves trying to catch their opponents out for making this mistake, and they pretend by doing so they’re defeating an attempt to undermine efforts to make the world more peaceful. It so happens that scientists actually have discovered a gene variation, known popularly as “the warrior gene,” that increases the likelihood that an individual carrying it will engage in aggressive behavior—but only if that individual experiences a traumatic childhood. Having a gene variation associated with a trait only ever means someone is more likely to express that trait, and there will almost always be other genes and several environmental factors contributing to the overall likelihood.

You can be reasonably sure that if a critic is taking a sociobiologist or an evolutionary psychologist to task for suggesting a direct one-to-one correspondence between a gene and a behavior that critic is being either careless or purposely misleading. In trying to bring about a more peaceful world, it’s far more effective to study the actual factors that contribute to violence than it is to write moralizing criticisms of scientific colleagues. The charge that evolutionary approaches can only be used to support conservative or reactionary views of society isn’t just a misrepresentation of sociobiological theories; it’s also empirically false—surveys demonstrate that grad students in evolutionary anthropology are overwhelmingly liberal in their politics, just as liberal in fact as anthropology students in non-evolutionary concentrations.

Another thing anyone who has taken a freshman anthropology course knows, but that anti-evolutionary critics fall all over themselves taking sociobiologists to task for not understanding, is that people who live in foraging or tribal cultures cannot be treated as perfect replicas of our Pleistocene ancestors, or as Povinelli calls them “prehistoric time capsules.” Hunters and gatherers are not “living fossils,” because they’ve been evolving just as long as people in industrialized societies, their histories and environments are unique, and it’s almost impossible for them to avoid being impacted by outside civilizations. If you flew two groups of foragers from different regions each into the territory of the other, you would learn quite quickly that each group’s culture is intricately adapted to the environment it originally inhabited. This does not mean, however, that evidence about how foraging and tribal peoples live is irrelevant to questions about human evolution.

As different as those two groups are, they are both probably living lives much more similar to those of our ancestors than anyone in industrialized societies. What evolutionary anthropologists and psychologists tend to be most interested in are the trends that emerge when several of these cultures are compared to one another. The Yanomamö actually subsist largely on slash-and-burn agriculture, and they live in groups much larger than those of most foraging peoples. Their culture and demographic patterns may therefore provide clues to how larger and more stratified societies developed after millennia of evolution in small, mobile bands. But, again, no one is suggesting the Yanomamö are somehow interchangeable with the people who first made this transition to more complex social organization historically.

The prehistoric time-capsule straw man often goes hand-in-hand with an implication that the anthropologists supposedly making the blunder see the people whose culture they study as somehow inferior, somehow less human than people who live in industrialized civilizations. It seems like a short step from this subtle dehumanization to the kind of whole-scale exploitation indigenous peoples are often made to suffer. But the sad truth is there are plenty of economic, religious, and geopolitical forces working against the preservation of indigenous cultures and the protection of indigenous people’s rights to make scapegoating scientists who gather cultural and demographic information completely unnecessary. And you can bet Napoleon Chagnon is, if anything, more outraged by the mistreatment of the Yanomamö than most of the activists who falsely accuse him of complicity, because he knows so many of them personally. Chagnon is particularly critical of Brazilian gold miners and Salesian missionaries, both of whom it seems have far more incentive to disrespect the Yanomamö culture (by supplanting their religion and moving them closer to civilization) and ravage the territory they inhabit. The Salesians’ reprisals for his criticisms, which entailed pulling strings to keep him out of the territory and efforts to create a public image of him as a menace, eventually provided fodder for his critics back home as well.

*******

In an article published in the journal American Anthropologist in 2004 titled Guilt by Association, about the American Anthropological Association’s compromised investigation of Tierney’s accusations against Chagnon, Thomas Gregor and Daniel Gross describe “chains of logic by which anthropological research becomes, at the end of an associative thread, an act of misconduct” (689). Quoting Defenders of the Truth, sociologist Ullica Segerstrale’s indispensable 2000 book on the sociobiology debate, Gregor and Gross explain that Chagnon’s postmodern accusers relied on a rhetorical strategy common among critics of evolutionary theories of human behavior—a strategy that produces something startlingly indistinguishable from spectral evidence. Segerstrale writes,

In their analysis of their target’s texts, the critics used a method I call moral reading. The basic idea behind moral reading was to imagine the worst possible political consequences of a scientific claim. In this way, maximum moral guilt might be attributed to the perpetrator of this claim. (206)

She goes on to cite a “glaring” example of how a scholar drew an imaginary line from sociobiology to Nazism, and then connected it to fascist behavioral control, even though none of these links were supported by any evidence (207). Gregor and Gross describe how this postmodern version of spectral evidence was used to condemn Chagnon.

In the case at hand, for example, the Report takes Chagnon to task for an article in Science on revenge warfare, in which he reports that “Approximately 30% of Yanomami adult male deaths are due to violence”(Chagnon 1988:985). Chagnon also states that Yanomami men who had taken part in violent acts fathered more children than those who had not. Such facts could, if construed in their worst possible light, be read as suggesting that the Yanomami are violent by nature and, therefore, undeserving of protection. This reading could give aid and comfort to the opponents of creating a Yanomami reservation. The Report, therefore, criticizes Chagnon for having jeopardized Yanomami land rights by publishing the Science article, although his research played no demonstrable role in the demarcation of Yanomami reservations in Venezuela and Brazil. (689)

The task force had found that Chagnon was guilty—even though it was nominally just an “inquiry” and had no official grounds for pronouncing on any misconduct—of harming the Indians by portraying them negatively. Gregor and Gross, however, sponsored a ballot at the AAA to rescind the organization’s acceptance of the report; in 2005, it was voted on by the membership and passed by a margin of 846 to 338. “Those five years,” Chagnon writes of the time between that email warning about Tierney’s book and the vote finally exonerating him, “seem like a blurry bad dream” (450).

Anthropological fieldwork has changed dramatically since Chagnon’s early research in Venezuela. There was legitimate concern about the impact of trading manufactured goods like machetes for information, and you can read about some of the fracases it fomented among the Yanomamö in Noble Savages. The practice is now prohibited by the ethical guidelines of ethnographic field research. The dangers to isolated or remote populations from communicable diseases must also be considered while planning any expeditions to study indigenous cultures. But Chagnon was entering the Ocamo region after many missionaries and just before many gold miners. And we can’t hold him accountable for disregarding rules that didn’t exist at the time. Sahlins, however, echoing Tierney’s perversion of Neel and Chagnon’s race to immunize the Indians so that the two men appeared to be the source of contagion, accuses Chagnon of causing much of the violence he witnessed and reported by spreading around his goods.

Hostilities thus tracked the always-changing geopolitics of Chagnon-wealth, including even pre-emptive attacks to deny others access to him. As one Yanomami man recently related to Tierney: “Shaki [Chagnon] promised us many things, and that’s why other communities were jealous and began to fight against us.”

Aside from the fact that some Yanomamö men had just returned from a raid the very first time he entered one of their villages, and the fact that the source of this quote has been discredited, Sahlins is also basing his elaborate accusation on some pretty paltry evidence.

Sahlins also insists that the “monster in Amazonia” couldn’t possibly have figured out a way to learn the names and relationships of the people he studied without aggravating intervillage tensions (thus implicitly conceding those tensions already existed). The Yanomamö have a taboo against saying the names of other adults, similar to our own custom of addressing people we’ve just met by their titles and last names, but with much graver consequences for violations. This is why Chagnon had to confirm the names of people in one tribe by asking about them in another, the practice that led to his discovery of the prank that was played on him. Sahlins uses Tierney’s reporting as the only grounds for his speculations on how disruptive this was to the Yanomamö. And, in the same way he suggested there was some moral equivalence between Chagnon going into the jungle to study the culture of a group of Indians and the US military going into the jungles to engage in a war against the Vietcong, he fails to distinguish between the Nazi practice of marking Jews and Chagnon’s practice of writing numbers on people’s arms to keep track of their problematic names. Quoting Chagnon, Sahlins writes,

“I began the delicate task of identifying everyone by name and numbering them with indelible ink to make sure that everyone had only one name and identity.” Chagnon inscribed these indelible identification numbers on people’s arms—barely 20 years after World War II.

This juvenile innuendo calls to mind Jon Stewart’s observation that it’s not until someone in Washington makes the first Hitler reference that we know a real political showdown has begun (and Stewart has had to make the point a few times again since then).

One of the things that makes this type of trashy pseudo-scholarship so insidious is that it often creates an indelible impression of its own. Anyone who reads Sahlins’ essay could be forgiven for thinking that writing numbers on people might really be a sign that he was dehumanizing them. Fortunately, Chagnon’s own accounts go a long way toward dispelling this suspicion. In one passage, he describes how he made the naming and numbering into a game for this group of people who knew nothing about writing:

I had also noted after each name the item that person wanted me to bring on my next visit, and they were surprised at the total recall I had when they decided to check me. I simply looked at the number I had written on their arm, looked the number up in my field book, and then told the person precisely what he had requested me to bring for him on my next trip. They enjoyed this, and then they pressed me to mention the names of particular people in the village they would point to. I would look at the number on the arm, look it up in my field book, and whisper his name into someone’s ear. The others would anxiously and eagerly ask if I got it right, and the informant would give an affirmative quick raise of the eyebrows, causing everyone to laugh hysterically. (157)

Needless to say, this is a far cry from using the labels to efficiently herd people into cargo trains to transport them to concentration camps and gas chambers. Sahlins disgraces himself by suggesting otherwise and by not distancing himself from Tierney when it became clear that his atrocious accusations were meritless.

Which brings us back to John Horgan. One week after the post in which he bragged about standing up to five email bullies who were urging him not to endorse Tierney’s book and took the opportunity to say he still stands by the mostly positive review, he published another post on Chagnon, this time about the irony of how close Chagnon’s views on war are to those of Margaret Mead, a towering figure in anthropology whose blank-slate theories sociobiologists often challenge. (Both of Horgan’s posts marking the occasion of Chagnon’s new book—neither of which quote from it—were probably written for publicity; his own book on war was published last year.) As I read the post, I came across the following bewildering passage:

Chagnon advocates have cited a 2011 paper by bioethicist Alice Dreger as further “vindication” of Chagnon. But to my mind Dreger’s paper—which wastes lots of verbiage bragging about all the research that she’s done and about how close she has gotten to Chagnon–generates far more heat than light. She provides some interesting insights into Tierney’s possible motives in writing Darkness in El Dorado, but she leaves untouched most of the major issues raised by Chagnon’s career.

Horgan’s earlier post was one of the first things I’d read in years about Chagnon, and Tierney’s accusations against him. I read Alice Dreger’s report on her investigation of those accusations, and the “inquiry” by the American Anthropological Association that ensued from them, shortly afterward. I kept thinking back to Horgan’s continuing endorsement of Tieney’s book as I read the report because she cites several other reports that establish, at the very least, that there was no evidence to support the worst of the accusations. My conclusion was that Horgan simply hadn’t done his homework. How could he endorse a work featuring such horrific accusations if he knew most of them, the most horrific in particular, had been disproved? But with this second post he was revealing that he knew the accusations were false—and yet he still hasn’t recanted his endorsement.

If you only read two supplements to Noble Savages, I recommend Dreger’s report and Emily Eakin’s profile of Chagnon in the New York Times. The one qualm I have about Eakin’s piece is that she too sacrifices the principle of presuming innocence in her effort to achieve journalistic balance, quoting Leslie Sponsel, one of the authors of the appalling email that sparked the AAA’s investigation of Chagnon, as saying, “The charges have not all been disproven by any means.” It should go without saying that the burden of proof is on the accuser. It should also go without saying that once the most atrocious of Tierney’s accusations were disproven the discussion of culpability should have shifted its focus away from Chagnon onto Tierney and his supporters. That it didn’t calls to mind the scene in The Crucible when an enraged John Proctor, whose wife is being arrested, shouts in response to an assurance that she’ll be released if she’s innocent—“If she is innocent! Why do you never wonder if Paris be innocent, or Abigail? Is the accuser always holy now? Were they born this morning as clean as God’s fingers?” (73). Aside from Chagnon himself, Dreger is about the only one who realized Tierney himself warranted some investigating.

Eakin echoes Horgan a bit when she faults the “zealous tone” of Dreger’s report. Indeed, at one point, Dreger compares Chagnon’s trial to Galileo’s being called before the Inquisition. The fact is, though, there’s an important similarity. One of the most revealing discoveries of Dreger’s investigation was that the members of the AAA task force knew Tierney’s book was full of false accusations but continued with their inquiry anyway because they were concerned about the organization’s public image. In an email to the sociobiologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Jane Hill, the head of the task force, wrote,

Burn this message. The book is just a piece of sleaze, that’s all there is to it (some cosmetic language will be used in the report, but we all agree on that). But I think the AAA had to do something because I really think that the future of work by anthropologists with indigenous peoples in Latin America—with a high potential to do good—was put seriously at risk by its accusations, and silence on the part of the AAA would have been interpreted as either assent or cowardice.

How John Horgan could have read this and still claimed that Dreger’s report “generates more heat than light” is beyond me. I can only guess that his judgment has been distorted by cognitive dissonance.

To Horgan's other complaints, that she writes too much about her methods and admits to having become friends with Chagnon, she might respond that there is so much real hysteria surrounding this controversy, along with a lot of commentary reminiscent of the type of ridiculous rhetoric one hears on cable news, it was important to distinguish her report from all the groundless and recriminatory he-said-she-said. As for the friendship, it came about over the course of Dreger’s investigation. This is important because, for one, it doesn’t suggest any pre-existing bias, and two, one of the claims by critics of Chagnon’s work is that the violence he reported was either provoked by the man himself, or represented some kind of mental projection of his own bellicose character onto the people he was studying.

Dreger’s friendship with Chagnon shows that he’s not the monster portrayed by those in the grip of moralizing hysteria. And if parts of her report strike many as sententious it’s probably owing to their unfamiliarity with how ingrained that hysteria has become. It seems odd that anyone would pronounce on the importance of evidence or fairness—but basic principles we usually take for granted where trammeled in the frenzy to condemn Chagnon.

If his enemies are going to compare him to Mengele, then a comparison with Galileo seems less extreme.

Dreger, it seems to me, deserves credit for bringing a sorely needed modicum of sanity to the discussion. And she deserves credit as well for being one of the only people commenting on the controversy who understands the devastating personal impact of such vile accusations. She writes,

Meanwhile, unlike Neel, Chagnon was alive to experience what it is like to be drawn-and-quartered in the international press as a Nazi-like experimenter responsible for the deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of Yanomamö. He tried to describe to me what it is like to suddenly find yourself accused of genocide, to watch your life’s work be twisted into lies and used to burn you.

So let’s make it clear: the scientific controversy over sociobiology and the scandal over Tierney’s discredited book are two completely separate issues. In light of the findings from all the investigations of Tierney’s claims, we should all, no matter our theoretical leanings, agree that Darkness in El Dorado is, in the words of Jane Hill, who headed a task force investigating it, “just a piece of sleaze.” We should still discuss whether it was appropriate or advisable for Chagnon to exchange machetes for information—I’d be interested to hear what he has to say himself, since he describes all kinds of frustrations the practice caused him in his book. We should also still discuss the relative threat of contagion posed by ethnographers versus missionaries, weighed of course against the benefits of inoculation campaigns.

But we shouldn’t discuss any ethical or scientific matter with reference to Darkness in El Dorado or its disgraced author aside from questions like: Why was the hysteria surrounding the book allowed to go so far? Why were so many people willing to scapegoat Chagnon? Why doesn’t anyone—except Alice Dreger—seem at all interested in bringing Tierney to justice in some way for making such outrageous accusations based on misleading or fabricated evidence? What he did is far worse than what Jonah Lehrer or James Frey did, and yet both of those men have publically acknowledged their dishonesty while no one has put even the slightest pressure on Tierney to publically admit wrongdoing.

There’s some justice to be found in how easy Tierney and all the self-righteous pseudo-scholars like Sahlins have made it for future (and present) historians of science to cast them as deluded and unscrupulous villains in the story of a great—but flawed, naturally—anthropologist named Napoleon Chagnon. There’s also justice to be found in how snugly the hysterical moralizers’ tribal animosity toward Chagnon, their dehumanization of him, fits within a sociobiological framework of violence and warfare. One additional bit of justice might come from a demonstration of how easily Tierney’s accusatory pseudo-reporting can be turned inside-out. Tierney at one point in his book accuses Chagnon of withholding names that would disprove the central finding of his famous Science paper, and reading into the fact that the ascendant theories Chagnon criticized were openly inspired by Karl Marx’s ideas, he writes,

Yet there was something familiar about Chagnon’s strategy of secret lists combined with accusations against ubiquitous Marxists, something that traced back to his childhood in rural Michigan, when Joe McCarthy was king. Like the old Yanomami unokais, the former senator from Wisconsin was in no danger of death. Under the mantle of Science, Tailgunner Joe was still firing away—undefeated, undaunted, and blessed with a wealth of off-spring, one of whom, a poor boy from Port Austin, had received a full portion of his spirit. (180)

Tierney had no evidence that Chagnon kept any data out of his analysis. Nor did he have any evidence regarding Chagnon’s ideas about McCarthy aside from what he thought he could divine from knowing where he grew up (he cited no surveys of opinions from the town either). His writing is so silly it would be laughable if we didn’t know about all the anguish it caused. Tierney might just as easily have tried to divine Chagnon’s feelings about McCarthyism based on his alma mater. It turns out Chagnon began attending classes at the University of Michigan, the school where he’d write the famous dissertation for his PhD that would become the classic anthropology text The Fierce People, just two decades after another famous alumnus, one who actually stood up to McCarthy at a time when he was enjoying the success of a historical play he'd written, an allegory on the dangers of moralizing hysteria, in particular the one we now call the Red Scare. His name was Arthur Miller.

Also read

Can't Win for Losing: Why There are So Many Losers in Literature and Why It Has to Change

And

The People Who Evolved Our Genes for Us: Christopher Boehm on Moral Origins

And

The Feminist Sociobiologist: An Appreciation of Sarah Blaffer Hrdy

Too Psyched for Sherlock: A Review of Maria Konnikova’s “Mastermind: How to Think like Sherlock Holmes”—with Some Thoughts on Science Education

Maria Konnikova’s book “Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes” got me really excited because if the science of psychology is ever brought up in discussions of literature, it’s usually the pseudoscience of Sigmund Freud. Konnikova, whose blog went a long way toward remedying that tragedy, wanted to offer up an alternative approach. However, though the book shows great promise, it’s ultimately disappointing.

Whenever he gets really drunk, my brother has the peculiar habit of reciting the plot of one or another of his favorite shows or books. His friends and I like to tease him about it—“Watch out, Dan’s drunk, nobody mention The Wire!”—and the quirk can certainly be annoying, especially if you’ve yet to experience the story first-hand. But I have to admit, given how blotto he usually is when he first sets out on one of his grand retellings, his ability to recall intricate plotlines right down to their minutest shifts and turns is extraordinary. One recent night, during a timeout in an epic shellacking of Notre Dame’s football team, he took up the tale of Django Unchained, which incidentally I’d sat next to him watching just the week before. Tuning him out, I let my thoughts shift to a post I’d read on The New Yorker’s cinema blog The Front Row.

In “The Riddle of Tarantino,” film critic Richard Brody analyzes the director-screenwriter’s latest work in an attempt to tease out the secrets behind the popular appeal of his creations and to derive insights into the inner workings of his mind. The post is agonizingly—though also at points, I must admit, exquisitely—overwritten, almost a parody of the grandiose type of writing one expects to find within the pages of the august weekly. Bemused by the lavish application of psychoanalytic jargon, I finished the essay pitying Brody for, in all his writerly panache, having nothing of real substance to say about the movie or the mind behind it. I wondered if he knows the scientific consensus on Freud is that his influence is less in the line of, say, a Darwin or an Einstein than of an L. Ron Hubbard.

What Brody and my brother have in common is that they were both moved enough by their cinematic experience to feel an urge to share their enthusiasm, complicated though that enthusiasm may have been. Yet they both ended up doing the story a disservice, succeeding less in celebrating the work than in blunting its impact. Listening to my brother’s rehearsal of the plot with Brody’s essay in mind, I wondered what better field there could be than psychology for affording enthusiasts discussion-worthy insights to help them move beyond simple plot references. How tragic, then, that the only versions of psychology on offer in educational institutions catering to those who would be custodians of art, whether in academia or on the mastheads of magazines like The New Yorker, are those in thrall to Freud’s cultish legacy.

There’s just something irresistibly seductive about the promise of a scientific paradigm that allows us to know more about another person than he knows about himself. In this spirit of privileged knowingness, Brody faults Django for its lack of moral complexity before going on to make a silly accusation. Watching the movie, you know who the good guys are, who the bad guys are, and who you want to see prevail in the inevitably epic climax. “And yet,” Brody writes,

the cinematic unconscious shines through in moments where Tarantino just can’t help letting loose his own pleasure in filming pain. In such moments, he never seems to be forcing himself to look or to film, but, rather, forcing himself not to keep going. He’s not troubled by representation but by a visual superego that restrains it. The catharsis he provides in the final conflagration is that of purging the world of miscreants; it’s also a refining fire that blasts away suspicion of any peeping pleasure at misdeeds and fuses aesthetic, moral, and political exultation in a single apotheosis.

The strained stateliness of the prose provides a ready distraction from the stark implausibility of the assessment. Applying Occam’s Razor rather than Freud’s at once insanely elaborate and absurdly reductionist ideology, we might guess that what prompted Tarantino to let the camera linger discomfortingly long on the violent misdeeds of the black hats is that he knew we in the audience would be anticipating that “final conflagration.”

The more outrageous the offense, the more pleasurable the anticipation of comeuppance—but the experimental findings that support this view aren’t covered in film or literary criticism curricula, mired as they are in century-old pseudoscience.

I’ve been eagerly awaiting the day when scientific psychology supplants psychoanalysis (as well as other equally, if not more, absurd ideologies) in academic and popular literary discussions. Coming across the blog Literally Psyched on Scientific American’s website about a year ago gave me a great sense of hope. The tagline, “Conceived in literature, tested in psychology,” as well as the credibility conferred by the host site, promised that the most fitting approach to exploring the resonance and beauty of stories might be undergoing a long overdue renaissance, liberated at last from the dominion of crackpot theorists. So when the author, Maria Konnikova, a doctoral candidate at Columbia, released her first book, I made a point to have Amazon deliver it as early as possible.

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes does indeed follow the conceived-in-literature-tested-in-psychology formula, taking the principles of sound reasoning expounded by what may be the most recognizable fictional character in history and attempting to show how modern psychology proves their soundness. In what she calls a “Prelude” to her book, Konnikova explains that she’s been a Holmes fan since her father read Conan Doyle’s stories to her and her siblings as children.

The one demonstration of the detective’s abilities that stuck with Konnikova the most comes when he explains to his companion and chronicler Dr. Watson the difference between seeing and observing, using as an example the number of stairs leading up to their famous flat at 221B Baker Street. Watson, naturally, has no idea how many stairs there are because he isn’t in the habit of observing. Holmes, preternaturally, knows there are seventeen steps. Ever since being made aware of Watson’s—and her own—cognitive limitations through this vivid illustration (which had a similar effect on me when I first read “A Scandal in Bohemia” as a teenager), Konnikova has been trying to find the secret to becoming a Holmesian observer as opposed to a mere Watsonian seer. Already in these earliest pages, we encounter some of the principle shortcomings of the strategy behind the book. Konnikova wastes no time on the question of whether or not a mindset oriented toward things like the number of stairs in your building has any actual advantages—with regard to solving crimes or to anything else—but rather assumes old Sherlock is saying something instructive and profound.

Mastermind is, for the most part, an entertaining read. Its worst fault in the realm of simple page-by-page enjoyment is that Konnikova often belabors points that upon reflection expose themselves as mere platitudes. The overall theme is the importance of mindfulness—an important message, to be sure, in this age of rampant multitasking. But readers get more endorsement than practical instruction. You can only be exhorted to pay attention to what you’re doing so many times before you stop paying attention to the exhortations. The book’s problems in both the literary and psychological domains, however, are much more serious. I came to the book hoping it would hold some promise for opening the way to more scientific literary discussions by offering at least a glimpse of what they might look like, but while reading I came to realize there’s yet another obstacle to any substantive analysis of stories. Call it the TED effect. For anything to be read today, or for anything to get published for that matter, it has to promise to uplift readers, reveal to them some secret about how to improve their lives, help them celebrate the horizonless expanse of human potential.

Naturally enough, with the cacophony of competing information outlets, we all focus on the ones most likely to offer us something personally useful. Though self-improvement is a worthy endeavor, the overlooked corollary to this trend is that the worthiness intrinsic to enterprises and ideas is overshadowed and diminished. People ask what’s in literature for me, or what can science do for me, instead of considering them valuable in their own right—and instead of thinking, heaven forbid, we may have a duty to literature and science as institutions serving as essential parts of the foundation of civilized society.

In trying to conceive of a book that would operate as a vehicle for her two passions, psychology and Sherlock Holmes, while at the same time catering to readers’ appetite for life-enhancement strategies and spiritual uplift, Konnikova has produced a work in the grip of a bewildering and self-undermining identity crisis. The organizing conceit of Mastermind is that, just as Sherlock explains to Watson in the second chapter of A Study in Scarlet, the brain is like an attic. For Konnikova, this means the mind is in constant danger of becoming cluttered and disorganized through carelessness and neglect. That this interpretation wasn’t what Conan Doyle had in mind when he put the words into Sherlock’s mouth—and that the meaning he actually had in mind has proven to be completely wrong—doesn’t stop her from making her version of the idea the centerpiece of her argument. “We can,” she writes,

learn to master many aspects of our attic’s structure, throwing out junk that got in by mistake (as Holmes promises to forget Copernicus at the earliest opportunity), prioritizing those things we want to and pushing back those that we don’t, learning how to take the contours of our unique attic into account so that they don’t unduly influence us as they otherwise might. (27)

This all sounds great—a little too great—from a self-improvement perspective, but the attic metaphor is Sherlock’s explanation for why he doesn’t know the earth revolves around the sun and not the other way around. He states quite explicitly that he believes the important point of similarity between attics and brains is their limited capacity. “Depend upon it,” he insists, “there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before.” Note here his topic is knowledge, not attention.

It is possible that a human mind could reach and exceed its storage capacity, but the way we usually avoid this eventuality is that memories that are seldom referenced are forgotten. Learning new facts may of course exhaust our resources of time and attention. But the usual effect of acquiring knowledge is quite the opposite of what Sherlock suggests. In the early 1990’s, a research team led by Patricia Alexander demonstrated that having background knowledge in a subject area actually increased participants’ interest in and recall for details in an unfamiliar text. One of the most widely known replications of this finding was a study showing that chess experts have much better recall for the positions of pieces on a board than novices. However, Sherlock was worried about information outside of his area of expertise. Might he have a point there?

The problem is that Sherlock’s vocation demands a great deal of creativity, and it’s never certain at the outset of a case what type of knowledge may be useful in solving it. In the story “The Lion’s Mane,” he relies on obscure information about a rare species of jellyfish to wrap up the mystery. Konnikova cites this as an example of “The Importance of Curiosity and Play.” She goes on to quote Sherlock’s endorsement for curiosity in The Valley of Fear: “Breadth of view, my dear Mr. Mac, is one of the essentials of our profession. The interplay of ideas and the oblique uses of knowledge are often of extraordinary interest” (151). How does she account for the discrepancy? Could Conan Doyle’s conception of the character have undergone some sort of evolution? Alas, Konnikova isn’t interested in questions like that. “As with most things,” she writes about the earlier reference to the attic theory, “it is safe to assume that Holmes was exaggerating for effect” (150). I’m not sure what other instances she may have in mind—it seems to me that the character seldom exaggerates for effect. In any case, he was certainly not exaggerating his ignorance of Copernican theory in the earlier story.

If Konnikova were simply privileging the science at the expense of the literature, the measure of Mastermind’s success would be in how clearly the psychological theories and findings are laid out. Unfortunately, her attempt to stitch science together with pronouncements from the great detective often leads to confusing tangles of ideas. Following her formula, she prefaces one of the few example exercises from cognitive research provided in the book with a quote from “The Crooked Man.” After outlining the main points of the case, she writes,

How to make sense of these multiple elements? “Having gathered these facts, Watson,” Holmes tells the doctor, “I smoked several pipes over them, trying to separate those which were crucial from others which were merely incidental.” And that, in one sentence, is the first step toward successful deduction: the separation of those factors that are crucial to your judgment from those that are just incidental, to make sure that only the truly central elements affect your decision. (169)

So far she hasn’t gone beyond the obvious. But she does go on to cite a truly remarkable finding that emerged from research by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the early 1980’s. People who read a description of a man named Bill suggesting he lacks imagination tended to feel it was less likely that Bill was an accountant than that he was an accountant who plays jazz for a hobby—even though the two points of information in that second description make in inherently less likely than the one point of information in the first. The same result came when people were asked whether it was more likely that a woman named Linda was a bank teller or both a bank teller and an active feminist. People mistook the two-item choice as more likely. Now, is this experimental finding an example of how people fail to sift crucial from incidental facts?

The findings of this study are now used as evidence of a general cognitive tendency known as the conjunction fallacy. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman explains how more detailed descriptions (referring to Tom instead of Bill) can seem more likely, despite the actual probabilities, than shorter ones. He writes,

The judgments of probability that our respondents offered, both in the Tom W and Linda problems, corresponded precisely to judgments of representativeness (similarity to stereotypes). Representativeness belongs to a cluster of closely related basic assessments that are likely to be generated together. The most representative outcomes combine with the personality description to produce the most coherent stories. The most coherent stories are not necessarily the most probable, but they are plausible, and the notions of coherence, plausibility, and probability are easily confused by the unwary. (159)

So people are confused because the less probable version is actually easier to imagine. But here’s how Konnikova tries to explain the point by weaving it together with Sherlock’s ideas:

Holmes puts it this way: “The difficulty is to detach the framework of fact—of absolute undeniable fact—from the embellishments of theorists and reporters. Then, having established ourselves upon this sound basis, it is our duty to see what inferences may be drawn and what are the special points upon which the whole mystery turns.” In other words, in sorting through the morass of Bill and Linda, we would have done well to set clearly in our minds what were the actual facts, and what were the embellishments or stories in our minds. (173)

But Sherlock is not referring to our minds’ tendency to mistake coherence for probability, the tendency that has us seeing more detailed and hence less probable stories as more likely. How could he have been? Instead, he’s talking about the importance of independently assessing the facts instead of passively accepting the assessments of others. Konnikova is fudging, and in doing so she’s shortchanging the story and obfuscating the science.

As the subtitle implies, though, Mastermind is about how to think; it is intended as a self-improvement guide. The book should therefore be judged based on the likelihood that readers will come away with a greater ability to recognize and avoid cognitive biases, as well as the ability to sustain the conviction to stay motivated and remain alert. Konnikova emphasizes throughout that becoming a better thinker is a matter of determinedly forming better habits of thought. And she helpfully provides countless illustrative examples from the Holmes canon, though some of these precepts and examples may not be as apt as she’d like. You must have clear goals, she stresses, to help you focus your attention. But the overall purpose of her book provides a great example of a vague and unrealistic end-point. Think better? In what domain? She covers examples from countless areas, from buying cars and phones, to sizing up strangers we meet at a party. Sherlock, of course, is a detective, so he focuses his attention of solving crimes. As Konnikova dutifully points out, in domains other than his specialty, he’s not such a mastermind.

What Mastermind works best as is a fun introduction to modern psychology. But it has several major shortcomings in that domain, and these same shortcomings diminish the likelihood that reading the book will lead to any lasting changes in thought habits. Concepts are covered too quickly, organized too haphazardly, and no conceptual scaffold is provided to help readers weigh or remember the principles in context. Konnikova’s strategy is to take a passage from Conan Doyle’s stories that seems to bear on noteworthy findings in modern research, discuss that research with sprinkled references back to the stories, and wrap up with a didactic and sententious paragraph or two. Usually, the discussion begins with one of Watson’s errors, moves on to research showing we all tend to make similar errors, and then ends admonishing us not to be like Watson. Following Kahneman’s division of cognition into two systems—one fast and intuitive, the other slower and demanding of effort—Konnikova urges us to get out of our “System Watson” and rely instead on our “System Holmes.” “But how do we do this in practice?” she asks near the end of the book,

How do we go beyond theoretically understanding this need for balance and open-mindedness and applying it practically, in the moment, in situations where we might not have as much time to contemplate our judgments as we do in the leisure of our reading?

The answer she provides: “It all goes back to the very beginning: the habitual mindset that we cultivate, the structure that we try to maintain for our brain attic no matter what” (240). Unfortunately, nowhere in her discussion of built-in biases and the correlates to creativity did she offer any step-by-step instruction on how to acquire new habits. Konnikova is running us around in circles to hide the fact that her book makes an empty promise.

Tellingly, Kahneman, whose work on biases Konnikova cites on several occasions, is much more pessimistic about our prospects for achieving Holmesian thought habits. In the introduction to Thinking, Fast and Slow, he says his goal is merely to provide terms and labels for the regular pitfalls of thinking to facilitate more precise gossiping. He writes,