READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

The Idiocy of Outrage: Sam Harris's Run-ins with Ben Affleck and Noam Chomsky

Too often, we’re convinced by the passion with which someone expresses an idea—and that’s why there’s so much outrage in the news and in other media. Sam Harris has had a particularly hard time combatting outrage with cogent arguments, because he’s no sooner expressed an idea than his interlocutor is aggressively misinterpreting it.

Every time Sam Harris engages in a public exchange of ideas, be it a casual back-and-forth or a formal debate, he has to contend with an invisible third party whose obnoxious blubbering dispels, distorts, or simply drowns out nearly every word he says. You probably wouldn’t be able to infer the presence of this third party from Harris’s own remarks or demeanor. What you’ll notice, though, is that fellow participants in the discussion, be they celebrities like Ben Affleck or eminent scholars like Noam Chomsky, respond to his comments—even to his mere presence—with a level of rancor easily mistakable for blind contempt. This reaction will baffle many in the audience. But it will quickly dawn on anyone familiar with Harris’s ongoing struggle to correct pernicious mischaracterizations of his views that these people aren’t responding to Harris at all, but rather to the dimwitted and evil caricature of him promulgated by unscrupulous journalists and intellectuals.

In his books on religion and philosophy, Harris plies his unique gift for cutting through unnecessary complications to shine a direct light on the crux of the issue at hand. Topics that other writers seem to go out of their way to make abstruse he manages to explore with jolting clarity and refreshing concision. But this same quality to his writing which so captivates his readers often infuriates academics, who feel he’s cheating by breezily refusing to represent an issue in all its grand complexity while neglecting to acknowledge his indebtedness to past scholars. That he would proceed in such a manner to draw actual conclusions—and unorthodox ones at that—these scholars see as hubris, made doubly infuriating by the fact that his books enjoy such a wide readership outside of academia. So, whether Harris is arguing on behalf of a scientific approach to morality or insisting we recognize that violent Islamic extremism is motivated not solely by geopolitical factors but also by straightforward readings of passages in Islamic holy texts, he can count on a central thread of the campaign against him consisting of the notion that he’s a journeyman hack who has no business weighing in on such weighty matters.

Sam Harris

Philosophers and religious scholars are of course free to challenge Harris’s conclusions, and it’s even possible for them to voice their distaste for his style of argumentation without necessarily violating any principles of reasoned debate. However, whenever these critics resort to moralizing, we must recognize that by doing so they’re effectively signaling the end of any truly rational exchange. For Harris, this often means a substantive argument never even gets a chance to begin. The distinction between debating morally charged topics on the one hand, and condemning an opponent as immoral on the other, may seem subtle, or academic even. But it’s one thing to argue that a position with moral and political implications is wrong; it’s an entirely different thing to become enraged and attempt to shout down anyone expressing an opinion you deem morally objectionable. Moral reasoning, in other words, can and must be distinguished from moralizing. Since the underlying moral implications of the issue are precisely what are under debate, giving way to angry indignation amounts to a pulling of rank—an effort to silence an opponent through the exercise of one’s own moral authority, which reveals a rather embarrassing sense of one’s own superior moral standing.

Unfortunately, it’s far too rarely appreciated that a debate participant who gets angry and starts wagging a finger is thereby demonstrating an unwillingness or an inability to challenge a rival’s points on logical or evidentiary grounds. As entertaining as it is for some to root on their favorite dueling demagogue in cable news-style venues, anyone truly committed to reason and practiced in its application realizes that in a debate the one who loses her cool loses the argument. This isn’t to say we should never be outraged by an opponent’s position. Some issues have been settled long enough, their underlying moral calculus sufficiently worked through, that a signal of disgust or contempt is about the only imaginable response. For instance, if someone were to argue, as Aristotle did, that slavery is excusable because some races are naturally subservient, you could be forgiven for lacking the patience to thoughtfully scrutinize the underlying premises. The problem, however, is that prematurely declaring an end to the controversy and then moving on to blanket moral condemnation of anyone who disagrees has become a worryingly common rhetorical tactic. And in this age of increasingly segmented and polarized political factions it’s more important than ever that we check our impulse toward sanctimony—even though it’s perhaps also harder than ever to do so.

Once a proponent of some unpopular idea starts to be seen as not merely mistaken but dishonest, corrupt, or bigoted, then playing fair begins to seem less obligatory for anyone wishing to challenge that idea. You can learn from casual Twitter browsing or from reading any number of posts on Salon.com that Sam Harris advocates a nuclear first strike against radical Muslims, supported the Bush administration’s use of torture, and carries within his heart an abiding hatred of Muslim people, all billion and a half of whom he believes are virtually indistinguishable from the roughly 20,000 militants making up ISIS. You can learn these things, none of which is true, because some people dislike Harris’s ideas so much they feel it’s justifiable, even imperative, to misrepresent his views, lest the true, more reasonable-sounding versions reach a wider receptive audience. And it’s not just casual bloggers and social media mavens who feel no qualms about spreading what they know to be distortions of Harris’s views; religious scholar Reza Aslan and journalist Glenn Greenwald both saw fit to retweet the verdict that he is a “genocidal fascist maniac,” accompanied by an egregiously misleading quote as evidence—even though Harris had by then discussed his views at length with both of these men.

It’s easy to imagine Ben Affleck doing some cursory online research to prep for his appearance on Real Time with Bill Maher and finding plenty of savory tidbits to prejudice him against Harris before either of them stepped in front of the cameras. But we might hope that a scholar of Noam Chomsky’s caliber wouldn’t be so quick to form an opinion of someone based on hearsay. Nonetheless, Chomsky responded to Harris’s recent overture to begin an email exchange to help them clear up their misconceptions about each other’s ideas by writing: “Perhaps I have some misconceptions about you. Most of what I’ve read of yours is material that has been sent to me about my alleged views, which is completely false”—this despite Harris having just quoted Chomsky calling him a “religious fanatic.” We must wonder, where might that characterization have come from if he’d read so little of Harris’s work?

Political and scholarly discourse would benefit immensely from a more widespread recognition of our natural temptation to recast points of intellectual disagreement as moral offenses, a temptation which makes it difficult to resist the suspicion that anyone espousing rival beliefs is not merely mistaken but contemptibly venal and untrustworthy. In philosophy and science, personal or so-called ad hominem accusations and criticisms are considered irrelevant and thus deemed out of bounds—at least in principle. But plenty of scientists and academics of every stripe routinely succumb to the urge to moralize in the midst of controversy. Thus begins the lamentable process by which reasoned arguments are all but inevitably overtaken by competing campaigns of character assassination. In service to these campaigns, we have an ever growing repertoire of incendiary labels with ever lengthening lists of criteria thought to reasonably warrant their application, so if you want to discredit an opponent all that’s necessary is a little creative interpretation, and maybe some selective quoting.

The really tragic aspect of this process is that as scrupulous and fair-minded as any given interlocutor may be, it’s only ever a matter of time before an unpopular message broadcast to a wider audience is taken up by someone who feels duty-bound to kill the messenger—or at least to besmirch the messenger’s reputation. And efforts at turning thoughtful people away from troublesome ideas before they ever even have a chance to consider them all too often meet with success, to everyone’s detriment. Only a small percentage of unpopular ideas may merit acceptance, but societies can’t progress without them.

Once we appreciate that we’re all susceptible to this temptation to moralize, the next most important thing for us to be aware of is that it becomes more powerful the moment we begin to realize ours are the weaker arguments. People in individualist cultures already tend to more readily rate themselves as exceptionally moral than as exceptionally intelligent. Psychologists call this tendency the Muhammed Ali effect (because the famous boxer once responded to a journalist’s suggestion that he’d purposely failed an Army intelligence test by quipping, “I only said I was the greatest, not the smartest”). But when researchers Jens Möller and Karel Savyon had study participants rate themselves after performing poorly on an intellectual task, they found that the effect was even more pronounced. Subjects in studies of the Muhammed Ali effect report believing that moral traits like fairness and honesty are more socially desirable than intelligence. They also report believing these traits are easier for an individual to control, while at the same time being more difficult to measure. Möller and Savyon theorize that participants in their study were inflating their already inflated sense of their own moral worth to compensate for their diminished sense of intellectual worth. While researchers have yet to examine whether this amplification of the effect makes people more likely to condemn intellectual rivals on moral grounds, the idea that a heightened estimation of moral worth could make us more likely to assert our moral authority seems a plausible enough extrapolation from the findings.

That Ben Affleck felt intimated by the prospect of having to intelligently articulate his reasons for rejecting Harris’s positions, however, seems less likely than that he was prejudiced to the point of outrage against Harris sometime before encountering him in person. At one point in the interview he says, “You’re making a career out of ISIS, ISIS, ISIS,” a charge of pandering that suggests he knows something about Harris’s work (though Harris doesn't discuss ISIS in any of his books). Unfortunately, Affleck’s passion and the sneering tone of his accusations were probably more persuasive for many in the audience than any of the substantive points made on either side. But, amid Affleck’s high dudgeon, it’s easy to sift out views that are mainstream among liberals. The argument Harris makes at the outset of the segment that first sets Affleck off—though it seemed he’d already been set off by something—is in fact a critique of those same views. He says,

When you want to talk about the treatment of women and homosexuals and freethinkers and public intellectuals in the Muslim world, I would argue that liberals have failed us. [Affleck breaks in here to say, “Thank God you’re here.”] And the crucial point of confusion is that we have been sold this meme of Islamophobia, where every criticism of the doctrine of Islam gets conflated with bigotry toward Muslims as people.

This is what Affleck says is “gross” and “racist.” The ensuing debate, such as it is, focuses on the appropriateness—and morality—of criticizing the Muslim world for crimes only a subset of Muslims are guilty of. But how large is that subset?

Harris (along with Maher) makes two important points: first, he states over and over that it’s Muslim beliefs he’s criticizing, not the Muslim people, so if a particular Muslim doesn’t hold to the belief in question he or she is exempt from the criticism. Harris is ready to cite chapter and verse of Islamic holy texts to show that the attitudes toward women and homosexuals he objects to aren’t based on the idiosyncratic characters of a few sadistic individuals but are rather exactly what’s prescribed by religious doctrine. A passage from his book The End of Faith makes the point eloquently.

It is not merely that we are war with an otherwise peaceful religion that has been “hijacked” by extremists. We are at war with precisely the vision of life that is prescribed to all Muslims in the Koran, and further elaborated in the literature of the hadith, which recounts the sayings and actions of the Prophet. A future in which Islam and the West do not stand on the brink of mutual annihilation is a future in which most Muslims have learned to ignore most of their canon, just as most Christians have learned to do. (109-10)

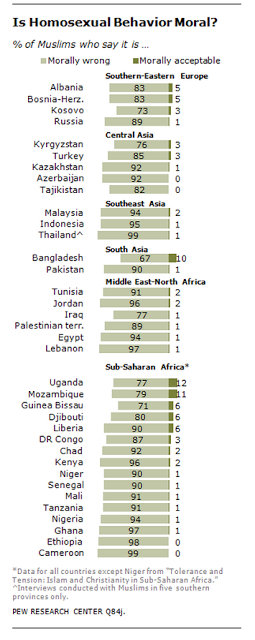

But most secularists and moderate Christians in the U.S. have a hard time appreciating how seriously most Muslims take their Koran. There are of course passages in the Bible that are simply obscene, and Christians have certainly committed their share of atrocities at least in part because they believed their God commanded them to. But, whereas almost no Christians today advocate stoning their brothers, sisters, or spouses to death for coaxing them to worship other gods (Deuteronomy 13:6 8-15), a significant number of people in Islamic populations believe apostates and “innovators” deserve to have their heads lopped off.

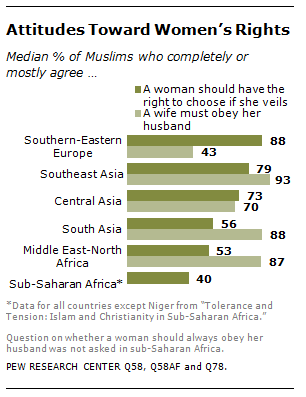

The second point Harris makes is that, while Affleck is correct in stressing how few Muslims make up or support the worst of the worst groups like Al Qaeda and ISIS, the numbers who believe women are essentially the property of their fathers and husbands, that homosexuals are vile sinners, or that atheist bloggers deserve to be killed are much higher. “We have to empower the true reformers in the Muslim world to change it,” as Harris insists. The journalist Nicholas Kristof says this is a mere “caricature” of the Muslim world. But Harris’s goal has never been to promote a negative view of Muslims, and he at no point suggests his criticisms apply to all Muslims, all over the world. His point, as he stresses multiple times, is that Islamic doctrine is inspiring large numbers of people to behave in appalling ways, and this is precisely why he’s so vocal in his criticisms of those doctrines.

Part of the difficulty here is that liberals (including this one) face a dilemma anytime they’re forced to account for the crimes of non-whites in non-Western cultures. In these cases, their central mission of standing up for the disadvantaged and the downtrodden runs headlong into their core principle of multiculturalism, which makes it taboo for them to speak out against another society’s beliefs and values. Guys like Harris are permitted to criticize Christianity when it’s used to justify interference in women’s sexual decisions or discrimination against homosexuals, because a white Westerner challenging white Western culture is just the system attempting to correct itself. But when Harris speaks out against Islam and the far worse treatment of women and homosexuals—and infidels and apostates—it prescribes, his position is denounced as “gross” and “racist” by the likes of Ben Affleck, with the encouragement of guys like Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald. A white American male casting his judgment on a non-Western belief system strikes them as the first step along the path to oppression that ends in armed invasion and possibly genocide. (Though, it should be noted, multiculturalists even attempt to silence female critics of Islam from the Muslim world.)

The biggest problem with this type of slippery-slope presumption isn’t just that it’s sloppy thinking—rejecting arguments because of alleged similarities to other, more loathsome ideas, or because of some imagined consequence should those ideas fall into the wrong hands. The biggest problem is that it time and again provides a rationale for opponents of an idea to silence and defame anyone advocating it. Unless someone is explicitly calling for mistreatment or aggression toward innocents who pose no threat, there’s simply no way to justify violating anyone’s rights to free inquiry and free expression—principles that should supersede multiculturalism because they’re the foundation and guarantors of so many other rights. Instead of using our own delusive moral authority in an attempt to limit discourse within the bounds we deem acceptable, we have a responsibility to allow our intellectual and political rivals the space to voice their positions, trusting in our fellow citizens’ ability to weigh the merits of competing arguments.

But few intellectuals are willing to admit that they place multiculturalism before truth and the right to seek and express it. And, for those who are reluctant to fly publically into a rage or to haphazardly apply any of the growing assortment of labels for the myriad varieties of bigotry, there are now a host of theories that serve to reconcile competing political values. The multicultural dilemma probably makes all of us liberals too quick to accept explanations of violence or extremism—or any other bad behavior—emphasizing the role of external forces, whether it’s external to the individual or external to the culture. Accordingly, to combat Harris’s arguments about Islam, many intellectuals insist that religion simply does not cause violence. They argue instead that the real cause is something like resource scarcity, a history of oppression, or the prolonged occupation of Muslim regions by Western powers.

If the arguments in support of the view that religion plays a negligible role in violence were as compelling as proponents insist they are, then it’s odd that they should so readily resort to mischaracterizing Harris’s positions when he challenges them. Glenn Greenwald, a journalist who believes religion is such a small factor that anyone who criticizes Islam is suspect, argues his case against Harris within an almost exclusively moral framework—not is Harris right, but is he an anti-Muslim? The religious scholar Reza Aslan quotes Harris out of context to give the appearance that he advocates preemptive strikes against Muslim groups. But Aslan’s real point of disagreement with Harris is impossible to pin down. He writes,

After all, there’s no question that a person’s religious beliefs can and often do influence his or her behavior. The mistake lies in assuming there is a necessary and distinct causal connection between belief and behavior.

Since he doesn’t explain what he means by “necessary and distinct,” we’re left with little more than the vague objection that religion’s role in motivating violence is more complex than some people seem to imagine. To make this criticism apply to Harris, however, Aslan is forced to erect a straw man—and to double down on the tactic after Harris has pointed out his error, suggesting that his misrepresentation is deliberate.

Few commenters on this debate appreciate just how radical Aslan’s and Greenwald’s (and Karen Armstrong’s) positions are. The straw men notwithstanding, Harris readily admits that religion is but one of many factors that play a role in religious violence. But this doesn’t go far enough for Aslan and Greenwald. While they acknowledge religion must fit somewhere in the mix, they insist its role is so mediated and mixed up with other factors that its influence is all but impossible to discern. Religion in their minds is a pure social construct, so intricately woven into the fabric of a culture that it could never be untangled. As evidence of this irreducible complexity, they point to the diverse interpretations of the Koran made by the wide variety of Muslim groups all over the world. There’s an undeniable kernel of truth in this line of thinking. But is religion really reconstructed from scratch in every culture?

One of the corollaries of this view is that all religions are essentially equal in their propensity to inspire violence, and therefore, if adherents of one particular faith happen to engage in disproportionate levels of violence, we must look to other cultural and political factors to explain it. That would also mean that what any given holy text actually says in its pages is completely immaterial. (This from a scholar who sticks to a literal interpretation of a truncated section of a book even though the author assures him he’s misreading it.) To highlight the absurdity of this idea, Harris likes to cite the Jains as an example. Mahavira, a Jain patriarch, gave this commandment: “Do not injure, abuse, oppress, enslave, insult, torment, or kill any creature or living being.” How plausible is the notion that adherents of this faith are no more and no less likely to commit acts of violence than those whose holy texts explicitly call for them to murder apostates? “Imagine how different our world might be if the Bible contained this as its central precept” (23), Harris writes in Letter to a Christian Nation.

Since the U.S. is in fact a Christian nation, and since it has throughout its history displaced, massacred, invaded, occupied, and enslaved people from nearly every corner of the globe, many raise the question of what grounds Harris, or any other American, has for judging other cultures. And this is where the curious email exchange Harris began with the linguist and critic of American foreign policy Noam Chomsky takes up. Harris reached out to Chomsky hoping to begin an exchange that might help to clear up their differences, since he figured they have a large number of readers in common. Harris had written critically of Chomsky’s book about 9/11 in End of Faith, his own book on the topic of religious extremism written some time later. Chomsky’s argument seems to have been that the U.S. routinely commits atrocities on a scale similar to that of 9/11, and that the Al Qaeda attacks were an expectable consequence of our nation’s bullying presence in global affairs. Instead of dealing with foreign threats then, we should be concentrating our efforts on reforming our own foreign policy. But Harris points out that, while it’s true the U.S. has caused the deaths of countless innocents, the intention of our leaders wasn’t to kill as many people as possible to send a message of terror, making such actions fundamentally different from those of the Al Qaeda terrorists.

The first thing to note in the email exchange is that Harris proceeds on the assumption that any misunderstanding of his views by Chomsky is based on an honest mistake, while Chomsky immediately takes for granted that Harris’s alleged misrepresentations are deliberate (even though, since Harris sends him the excerpt from his book, that would mean he’s presenting the damning evidence of his own dishonesty). In other words, Chomsky switches into moralizing mode at the very outset of the exchange. The substance of the disagreement mainly concerns the U.S.’s 1998 bombing of the al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Sudan. According to Harris’s book, Chomsky argues this attack was morally equivalent to the attacks by Al Qaeda on 9/11. But in focusing merely on body counts, Harris charges that Chomsky is neglecting the far more important matter of intention.

Noam Chomsky

Chomsky insists after reading the excerpt, however, that he never claimed the two attacks were morally equivalent, and that furthermore he in fact did consider, and write at length about, the intentions of the Clinton administration officials who decided to bomb al-Shifa—just not in the book cited by Harris. In this other book, which Chomsky insists Harris is irresponsible for not having referenced, he argues that the administration’s claim that it received intelligence about the factory manufacturing chemical weapons was a lie and that the bombing was actually meant as retaliation for an earlier attack on the U.S. Embassy. Already at this point in the exchange Chomsky is writing to Harris as if he were guilty of dishonesty, unscholarly conduct, and collusion in covering up the crimes of the American government.

But which is it? Is Harris being dishonest when he says Chomsky is claiming moral equivalence? Or is he being dishonest when he fails to cite an earlier source arguing that in fact what the U.S. did was morally worse? The more important question, however, is why does Chomsky assume Harris is being dishonest, especially in light of how complicated his position is? Here’s what Chomsky writes in response to Harris pressing him to answer directly the question about moral equivalence:

Clinton bombed al-Shifa in reaction to the Embassy bombings, having discovered no credible evidence in the brief interim of course, and knowing full well that there would be enormous casualties. Apologists may appeal to undetectable humanitarian intentions, but the fact is that the bombing was taken in exactly the way I described in the earlier publication which dealt the question of intentions in this case, the question that you claimed falsely that I ignored: to repeat, it just didn’t matter if lots of people are killed in a poor African country, just as we don’t care if we kill ants when we walk down the street. On moral grounds, that is arguably even worse than murder, which at least recognizes that the victim is human. That is exactly the situation.

Most of the rest of the exchange consists of Harris trying to figure out Chomsky’s views on the role of intention in moral judgment, and Chomsky accusing Harris of dishonesty and evasion for not acknowledging and exploring the implications of the U.S.’s culpability in the al-Shifa atrocity. When Harris tries to explain his view on the bombing by describing a hypothetical scenario in which one group stages an attack with the intention of killing as many people as possible, comparing it to another scenario in which a second group stages an attack with the intention of preventing another, larger attack, killing as few people as possible in the process, Chomsky will have none it. He insists Harris’s descriptions are “so ludicrous as to be embarrassing,” because they’re nothing like what actually happened. We know Chomsky is an intelligent enough man to understand perfectly well how a thought experiment works. So we’re left asking, what accounts for his mindless pounding on the drum of the U.S.’s greater culpability? And, again, why is he so convinced Harris is carrying on in bad faith?

What seems to be going on here is that Chomsky, a long-time critic of American foreign policy, actually began with the conclusion he sought to arrive at. After arguing for decades that the U.S. was the ultimate bad guy in the geopolitical sphere, his first impulse after the attacks of 9/11 was to salvage his efforts at casting the U.S. as the true villain. Toward that end, he lighted on al-Shifa as the ideal crime to offset any claim to innocent victimhood. He’s actually been making this case for quite some time, and Harris is by no means the first to insist that the intentions behind the two attacks should make us judge them very differently. Either Chomsky felt he knew enough about Harris to treat him like a villain himself, or he has simply learned to bully and level accusations against anyone pursuing a line of questions that will expose the weakness of his idea—he likens Harris’s arguments at one point to “apologetics for atrocities”—a tactic he keeps getting away with because he has a large following of liberal academics who accept his moral authority.

Harris saw clear to the end-game of his debate with Chomsky, and it’s quite possible Chomsky in some murky way did as well. The reason he was so sneeringly dismissive of Harris’s attempts to bring the discussion around to intentions, the reason he kept harping on how evil America had been in bombing al-Shifa, is that by focusing on this one particular crime he was avoiding the larger issue of competing ideologies. Chomsky’s account of the bombing is not as certain as he makes out, to say the least. An earlier claim he made about a Human Rights Watch report on the death toll, for instance, turned out to be completely fictitious. But even if the administration really was lying about its motives, it’s noteworthy that a lie was necessary. When Bin Laden announced his goals, he did so loudly and proudly.

Chomsky’s one defense of his discounting of the attackers’ intentions (yes, he defends it, even though he accused Harris of being dishonest for pointing it out) is that everyone claims to have good intentions, so intentions simply don’t matter. This is shockingly facile coming from such a renowned intellectual—it would be shockingly facile coming from anyone. Of course Harris isn’t arguing that we should take someone’s own word for whether their intentions are good or bad. What Harris is arguing is that we should examine someone’s intentions in detail and make our own judgment about them. Al Qaeda’s plan to maximize terror by maximizing the death count of their attacks can only be seen as a good intention in the context of the group’s extreme religious ideology. That’s precisely why we should be discussing and criticizing that ideology, criticism which should extend to the more mainstream versions of Islam it grew out of.

Taking a step back from the particulars, we see that Chomsky believes the U.S. is guilty of far more and far graver acts of terror than any of the groups or nations officially designated as terrorist sponsors, and he seems unwilling to even begin a conversation with anyone who doesn’t accept this premise. Had he made some iron-clad case that the U.S. really did treat the pharmaceutical plant, and the thousands of lives that depended on its products, as pawns in some amoral game of geopolitical chess, he could have simply directed Harris to the proper source, or he could have reiterated key elements of that case. Regardless of what really happened with al-Shifa, we know full well what Al Qaeda’s intentions were, and Chomsky could have easily indulged Harris in discussing hypotheticals had he not feared that doing so would force him to undermine his own case. Is Harris an apologist for American imperialism? Here’s a quote from the section of his book discussing Chomsky's ideas:

We have surely done some terrible things in the past. Undoubtedly, we are poised to do terrible things in the future. Nothing I have written in this book should be construed as a denial of these facts, or as defense of state practices that are manifestly abhorrent. There may be much that Western powers, and the United States in particular, should pay reparations for. And our failure to acknowledge our misdeeds over the years has undermined our credibility in the international community. We can concede all of this, and even share Chomsky’s acute sense of outrage, while recognizing that his analysis of our current situation in the world is a masterpiece of moral blindness.

To be fair, lines like this last one are inflammatory, so it was understandable that Chomsky was miffed, up to a point. But Harris is right to point to his moral blindness, the same blindness that makes Aslan, Affleck, and Greenwald unable to see that the specific nature of beliefs and doctrines and governing principles actually matters. If we believe it’s evil to subjugate women, abuse homosexuals, and murder freethinkers, the fact that our country does lots of horrible things shouldn’t stop us from speaking out against these practices to people of every skin color, in every culture, on every part of the globe.

Sam Harris is no passive target in all of this. In a debate, he gives as good or better than he gets, and he has a penchant for finding the most provocative way to phrase his points—like calling Islam “the motherlode of bad ideas.” He doesn’t hesitate to call people out for misrepresenting his views and defaming him as a person, but I’ve yet to see him try to win an argument by going after the person making it. And I’ve never seen him try to sabotage an intellectual dispute with a cheap performance of moral outrage, or discredit opponents by fixing them with labels they don't deserve. Reading his writings and seeing him lecture or debate, you get the sense that he genuinely wants to test the strength of ideas against each other and see what new insight such exchanges may bring. That’s why it’s frustrating to see these discussions again and again go off the rails because his opponent feels justified in dismissing and condemning him based on inaccurate portrayals, from an overweening and unaccountable sense of self-righteousness.

Ironically, honoring the type of limits to calls for greater social justice that Aslan and Chomsky take as sacrosanct—where the West forebears to condescend to the rest—serves more than anything else to bolster the sense of division and otherness that makes many in the U.S. care so little about things like what happened in al-Shifa. As technology pushes on the transformation of our far-flung societies and diverse cultures into a global community, we ought naturally to start seeing people from Northern Africa and the Middle East—and anywhere else—not as scary and exotic ciphers, but as fellow citizens of the world, as neighbors even. This same feeling of connection that makes us all see each other as more human, more worthy of each other’s compassion and protection, simultaneously opens us up to each other’s criticisms and moral judgments. Chomsky is right that we Americans are far too complacent about our country’s many crimes. But opening the discussion up to our own crimes opens it likewise to other crimes that cannot be tolerated anywhere on the globe, regardless of the culture, regardless of any history of oppression, and regardless too of any sanction delivered from the diverse landscape of supposedly sacred realms.

Other popular posts like this:

THE SOUL OF THE SKEPTIC: WHAT PRECISELY IS SAM HARRIS WAKING UP FROM?

MEDIEVAL VS ENLIGHTENED: SORRY, MEDIEVALISTS, DAN SAVAGE WAS RIGHT

Capuchin-22: A Review of “The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism among the Primates” by Frans De Waal

THE SELF-RIGHTEOUSNESS INSTINCT: STEVEN PINKER ON THE BETTER ANGELS OF MODERNITY AND THE EVILS OF MORALITY

Medieval vs Enlightened: Sorry, Medievalists, Dan Savage Was Right

The medievalist letter writer claims that being “part of the center” is what makes living in the enlightened West preferable to living in the 12th century. But there’s simply no way whoever wrote the letter actually believes this. If you happen to be poor, female, a racial or religious minority, a homosexual, or a member of any other marginalized group, you’d be far more loath to return to the Middle Ages than those of us comfortably ensconced in this notional center, just as you’d be loath to relocate to any society not governed by Enlightenment principles today.

A letter from an anonymous scholar of the medieval period to the sex columnist Dan Savage has been making the rounds of social media lately. Responding to a letter from a young woman asking how she should handle sex for the first time with her Muslim boyfriend, who happened to be a virgin, Savage wrote, “If he’s still struggling with the sex-negative, woman-phobic zap that his upbringing (and a medieval version of his faith) put on his head, he needs to work through that crap before he gets naked with you.” The anonymous writer bristles in bold lettering at Savage’s terminology: “I’m a medievalist, and this is one of the things about our current discourse on religion that drives me nuts. Contemporary radical Christianity, Judaism, and Islam are all terrible, but none of them are medieval, especially in terms of sexuality.” Oddly, however, the letter, published under the title, “A Medievalist Schools Dan on Medieval Attitudes toward Sex,” isn’t really as much about correcting popular misconceptions about sex in the Middle Ages as it is about promoting a currently fashionable but highly dubious way of understanding radical religion in the various manifestations we see today.

While the medievalist’s overall argument is based far more on ideology than actual evidence, the letter does make one important and valid point. As citizens of a technologically advanced secular democracy, it’s tempting for us to judge other cultures by the standards of our own. Just as each of us expects every young person we encounter to follow a path to maturity roughly identical to the one we’ve taken ourselves, people in advanced civilizations tend to think of less developed societies as occupying one or another of the stages that brought us to our own current level of progress. This not only inspires a condescending attitude toward other cultures; it also often leads to an overly simplified understanding of our own culture’s history. The letter to Savage explains:

I’m not saying that the Middle Ages was a great period of freedom (sexual or otherwise), but the sexual culture of 12th-century France, Iraq, Jerusalem, or Minsk did not involve the degree of self-loathing brought about by modern approaches to sexuality. Modern sexual purity has become a marker of faith, which it wasn’t in the Middle Ages. (For instance, the Bishop of Winchester ran the brothels in South London—for real, it was a primary and publicly acknowledged source of his revenue—and one particularly powerful Bishop of Winchester was both the product of adultery and the father of a bastard, which didn’t stop him from being a cardinal and papal legate.) And faith, especially in modern radical religion, is a marker of social identity in a way it rarely was in the Middle Ages.

If we imagine the past as a bad dream of sexual repression from which our civilization has only recently awoken, historical tidbits about the prevalence and public acceptance of prostitution may come as a surprise. But do these revelations really undermine any characterization of the period as marked by religious suppression of sexual freedom?

Obviously, the letter writer’s understanding of the Middle Ages is more nuanced than most of ours, but the argument reduces to pointing out a couple of random details to distract us from the bigger picture. The passage quoted above begins with an acknowledgement that the Middle Ages was not a time of sexual freedom, and isn’t it primarily that lack of freedom that Savage was referring to when he used the term medieval? The point about self-loathing is purely speculative if taken to apply to the devout generally, and simply wrong with regard to ascetics who wore hairshirts, flagellated themselves, or practiced other forms of mortification of the flesh. In addition, we must wonder how much those prostitutes enjoyed the status conferred on them by the society that was supposedly so accepting of their profession; we must also wonder if this medievalist is aware of what medieval Islamic scholars like Imam Malik (711-795) and Imam Shafi (767-820) wrote about homosexuality. The letter writer is on shaky ground yet again with regard to the claim that sexual purity wasn’t a marker of faith (though it’s hard to know precisely what the phrase even means). There were all kinds of strange prohibitions in Christendom against sex on certain days of the week, certain times of the year, and in any position outside of missionary. Anyone watching the BBC’s adaptation of Wolf Hall knows how much virginity was prized in women—as King Henry VIII could only be wed to a woman who’d never had sex with another man. And there’s obviously an Islamic tradition of favoring virgins, or else why would so many of them be promised to martyrs? Finally, of course faith wasn’t a marker of social identity—nearly everyone in every community was of the same faith. If you decided to take up another set of beliefs, chances are you’d have been burned as a heretic or beheaded as an apostate.

The letter writer is eager to make the point that the sexual mores espoused by modern religious radicals are not strictly identical to the ones people lived according to in the Middle Ages. Of course, the varieties of religion in any one time aren’t ever identical to those in another, or even to others in the same era. Does anyone really believe otherwise? The important question is whether there’s enough similarity between modern religious beliefs on the one hand and medieval religious beliefs on the other for the use of the term to be apposite. And the answer is a definitive yes. So what is the medievalist’s goal in writing to correct Savage? The letter goes on,

The Middle Eastern boyfriend wasn’t taught a medieval version of his faith, and radical religion in the West isn’t a retreat into the past—it is a very modern way of conceiving identity. Even something like ISIS is really just interested in the medieval borders of their caliphate; their ideology developed out of 18th- and 19th-century anticolonial sentiment. The reason why this matters (beyond medievalists just being like, OMG no one gets us) is that the common response in the West to religious radicalism is to urge enlightenment, and to believe that enlightenment is a progressive narrative that is ever more inclusive. But these religions are responses to enlightenment, in fact often to The Enlightenment.

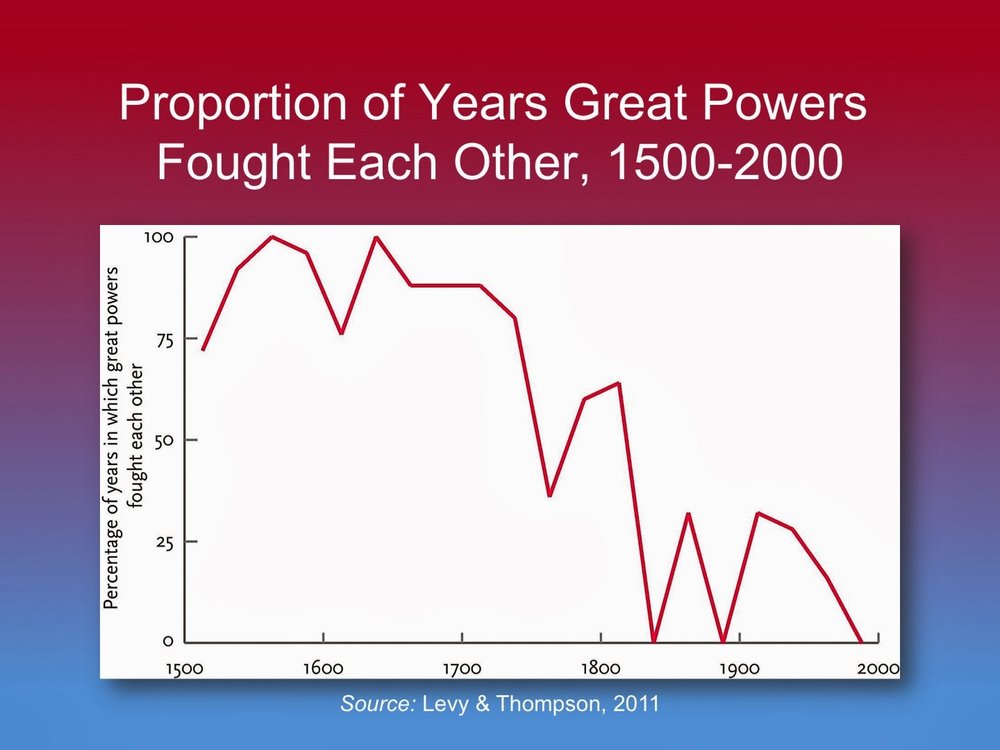

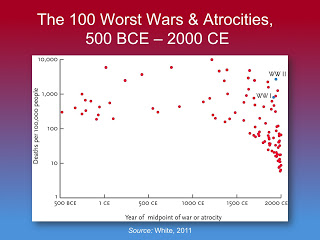

The Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, is popularly thought to have been the end of the Middle or so-called Dark Ages. The story goes that the medieval period was a time of Catholic oppression, feudal inequality, stunted innovation, and rampant violence. Then some brilliant philosophers woke the West up to the power of reason, science, and democracy, thus marking the dawn of the modern world. Historians and academics of various stripes like to sneer at this story of straightforward scientific and moral progress. It’s too simplistic. It ignores countless atrocities perpetrated by those supposedly enlightened societies. And it undergirds an ugly contemptuousness toward less advanced cultures. But is the story of the Enlightenment completely wrong?

The medievalist letter writer makes no bones about the source of his ideas, writing in a parenthetical, “Michel Foucault does a great job of talking about these developments, and modern sexuality, including homosexual and heterosexual identity, as well—and I’m stealing and watering down his thoughts here.” Foucault, though he eschewed the label, is a leading figure in poststructuralist and postmodern schools of thought. His abiding interest throughout his career was with the underlying dynamics of social power as they manifested themselves in the construction of knowledge. He was one of those French philosophers who don’t believe in things like objective truth, human nature, or historical progress of any kind.

Foucault and the scores of scholars inspired by his work take it as their mission to expose all the hidden justifications for oppression in our culture’s various media for disseminating information. Why they would bother taking on this mission in the first place, though, is a mystery, beginning as they do from the premise that any notion of moral progress can only be yet another manifestation of one group’s power over another. If you don’t believe in social justice, why pursue it? If you don’t believe in truth, why seek it out? And what are Foucault’s ideas about the relationship between knowledge and power but theories of human nature? Despite this fundamental incoherence, many postmodern academics today zealously pounce on any opportunity to chastise scientists, artists, and other academics for alleged undercurrents in their work of sexism, racism, homophobia, Islamophobia, or some other oppressive ideology. Few sectors of academia remain untouched by this tradition, and its influence leads legions of intellectuals to unselfconsciously substitute sanctimony for real scholarship.

So how do Foucault and the medievalist letter writer view the Enlightenment? The letter refers vaguely to “concepts of mass culture and population.” Already, it seems we’re getting far afield of how most historians and philosophers characterize the Enlightenment, not to mention how most Enlightenment figures themselves described their objectives. The letter continues,

Its narrative depends upon centralized control: It gave us the modern army, the modern prison, the mental asylum, genocide, and totalitarianism as well as modern science and democracy. Again, I’m not saying that I’d prefer to live in the 12th century (I wouldn’t), but that’s because I can imagine myself as part of that center. Educated, well-off Westerners generally assume that they are part of the center, that they can affect the government and contribute to the progress of enlightenment. This means that their identity is invested in the social form of modernity.

It’s true that the terms Enlightenment and Dark Ages were first used by Western scholars in the nineteenth century as an exercise in self-congratulation, and it’s also true that any moral progress that was made over the period occurred alongside untold atrocities. But neither of these complications to the oversimplified version of the narrative establishes in any way that the Enlightenment never really occurred—as the letter writer’s repeated assurances that it’s preferable to be alive today ought to make clear. What’s also clear is that this medievalist is deliberately conflating enlightenment with modernity, so that all the tragedies and outrages of the modern world can be laid at the feet of enlightenment thinking. How else could he describe the enlightenment as being simultaneously about both totalitarianism and democracy? But not everything that happened after the Enlightenment was necessarily caused by it, and nor should every social institution that arose from the late 19th to the early 20th century be seen as representative of enlightenment thinking.

The medievalist letter writer claims that being “part of the center” is what makes living in the enlightened West preferable to living in the 12th century. But there’s simply no way whoever wrote the letter actually believes this. If you happen to be poor, female, a racial or religious minority, a homosexual, or a member of any other marginalized group, you’d be far more loath to return to the Middle Ages than those of us comfortably ensconced in this notional center, just as you’d be loath to relocate to any society not governed by Enlightenment principles today.

The medievalist insists that groups like ISIS follow an ideology that dates to the 18th and 19th centuries and arose in response to colonialism, implying that Islamic extremism would be just another consequence of the inherently oppressive nature of the West and its supposedly enlightened ideas. “Radical religion,” from this Foucauldian perspective, offers a social identity to those excluded (or who feel excluded) from the dominant system of Western enlightenment capitalism. It is a modern response to a modern problem, and by making it seem like some medieval holdover, we cover up the way in which our own social power produces the conditions for this kind of identity, thus making violence appear to be the only response for these recalcitrant “holdouts.”

This is the position of scholars and journalists like Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald as well. It’s emblematic of the same postmodern ideology that forces on us the conclusion that if chimpanzees are violent to one another, it must be the result of contact with primatologists and other humans; if indigenous people in traditionalist cultures go to war with their neighbors, it must be owing to contact with missionaries and anthropologists; and if radical Islamists are killing their moderate co-religionists, kidnapping women, or throwing homosexuals from rooftops, well, it can only be the fault of Western colonialism. Never mind that these things are prescribed by holy texts dating from—you guessed it—the Middle Ages. The West, to postmodernists, is the source of all evil, because the West has all the power.

Directionality in Societal Development

But the letter writer’s fear that thinking of radical religion as a historical holdover will inevitably lead us to conclude military action is the only solution is based on an obvious non sequitur. There’s simply no reason someone who sees religious radicalism as medieval must advocate further violence to stamp it out. And that brings up another vital question: what solution do the postmodernists propose for things like religious violence in the Middle East and Africa? They seem to think that if they can only convince enough people that Western culture is inherently sexist, racist, violent, and so on—basically a gargantuan engine of oppression—then every geopolitical problem will take care of itself somehow.

If it’s absurd to believe that everything that comes from the West is good and pure and true just because it comes from the West, it’s just as absurd to believe that everything that comes from the West is evil and tainted and false for the same reason. Had the medievalist spent some time reading the webpage on the Enlightenment so helpfully hyperlinked to in the letter, whoever it is may have realized how off-the-mark Foucault’s formulation was. The letter writer gets it exactly wrong in the part about mass culture and population, since the movement is actually associated with individualism, including individual rights. But what best distinguishes enlightenment thinking from medieval thinking, in any region or era, is the conviction that knowledge, justice, and better lives for everyone in the society are achievable through the application of reason, science, and skepticism, while medieval cultures rely instead on faith, scriptural or hierarchical authority, and tradition. The two central symbols of the Enlightenment are Galileo declaring that the church was wrong to dismiss the idea of a heliocentric cosmos and the Founding Fathers appending the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution. You can argue that it’s only owing to a history of colonialism that Western democracies today enjoy the highest standard of living among all the nations of the globe. But even the medievalist letter writer attests to how much better it is to live in enlightened countries today than in the same countries in the Middle Ages.

The postmodernism of Foucault and his kindred academics is not now, and has not ever been, compelling on intellectual grounds, which leaves open the question of why so many scholars have turned against the humanist and Enlightenment ideals that once gave them their raison d’être. I can’t help suspecting that the appeal of postmodernism stems from certain religious qualities of the worldview, qualities that ironically make it resemble certain aspects of medieval thought: the bowing to the authority of celebrity scholars (mostly white males), the cloistered obsession with esoteric texts, rituals of expiation and self-abasement, and competitive finger-wagging. There’s even a core belief in something very like original sin; only in this case it consists of being born into the ranks of a privileged group whose past members were guilty of some unspeakable crime. Postmodern identity politics seems to appeal most strongly to whites with an overpowering desire for acceptance by those less fortunate, as if they were looking for some kind of forgiveness or redemption only the oppressed have the power to grant. That’s why these academics are so quick to be persuaded they should never speak up unless it’s on behalf of some marginalized group, as if good intentions were proof against absurdity. As safe and accommodating and well-intentioned as this stance sounds, though, in practice it amounts to little more than moral and intellectual cowardice.

Life really has gotten much better since the Enlightenment, and it really does continue to get better for an increasing number of formerly oppressed groups of people today. All this progress has been made, and continues being made, precisely because there are facts and ideas—scientific theories, human rights, justice, and equality—that transcend the social conditions surrounding their origins. Accepting this reality doesn’t in any way mean seeing violence as the only option for combatting religious extremism, despite many academics’ insistence to the contrary. Nor does it mean abandoning the cause of political, cultural, and religious pluralism. But, if we continue disavowing the very ideals that have driven this progress, however fitfully and haltingly it has occurred, if we continue denying that it can even be said to have occurred at all, then what hope can we possibly have of pushing it even further along in the future?

Also read:

THE IDIOCY OF OUTRAGE: SAM HARRIS'S RUN-INS WITH BEN AFFLECK AND NOAM CHOMSKY

And:

And:

And:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

On ISIS's explicit avowal of adherence to medieval texts: “What ISIS Really Wants" by Graeme Wood of the Atlantic

Are 1 in 5 Women Really Sexually Assaulted on College Campuses?

If you wanted to know how many young women are sexually assaulted on college campuses, you could easily devise a survey to ask a sample of them directly. But that’s not what advocates of stricter measures to prevent assault tend to do. Instead, they ask ambiguous questions they go on to interpret as suggesting an assault occurred. This almost guarantees wildly inflated numbers.

If you were a university administrator and you wanted to know how prevalent a particular experience was for students on campus, you would probably conduct a survey that asked a few direct questions about that experience—foremost among them the question of whether the student had at some point had the experience you’re interested in. Obvious, right? Recently, we’ve been hearing from many news media sources, and even from President Obama himself, that one in five college women experience sexual assault at some time during their tenure as students. It would be reasonable to assume that the surveys used to arrive at this ratio actually asked the participants directly whether or not they had been assaulted.

But it turns out the web survey that produced the one-in-five figure did no such thing. Instead, it asked students whether they had had any of several categories of experience the study authors later classified as sexual assault, or attempted sexual assault, in their analysis. This raises the important question of how we should define sexual assault when we’re discussing the issue—along with the related question of why we’re not talking about a crime that’s more clearly defined, like rape.

Of course, whatever you call it, sexual violence is such a horrible crime that most of us are willing to forgive anyone who exaggerates the numbers or paints an overly frightening picture of reality in an attempt to prevent future cases. (The issue is so serious that PolitiFact refrained from applying their trademark Truth-O-Meter to the one-in-five figure.)

But there are four problems with this attitude. The first is that for every supposed assault there is an alleged perpetrator. Dramatically overestimating the prevalence of the crime comes with the attendant risk of turning public perception against the accused, making it more difficult for the innocent to convince anyone of their innocence.

The second problem is that by exaggerating the danger in an effort to protect college students we’re sabotaging any opportunity these young adults may have to make informed decisions about the risks they take on. No one wants students to die in car accidents either, but we don’t manipulate the statistics to persuade them one in five drivers will die in a crash before they graduate from college.

The third problem is that going to college and experimenting with sex are for many people a wonderful set of experiences they remember fondly for the rest of their lives. Do we really want young women to barricade themselves in their dorms? Do we want young men to feel like they have to get signed and notarized documentation of consent before they try to kiss anyone? The fourth problem I’ll get to in a bit.

We need to strike some appropriate balance in our efforts to raise awareness without causing paranoia or inspiring unwarranted suspicion. And that balance should be represented by the results of our best good-faith effort to arrive at as precise an understanding of the risk as our most reliable methods allow. For this purpose, The Department of Justice’s Campus Sexual Assault Study, the source of the oft-cited statistic, is all but completely worthless. It has limitations, to begin with, when it comes to representativeness, since it surveyed students on just two university campuses. And, while the overall sample was chosen randomly, the 42% response rate implies a great deal of self-selection on behalf of the participants. The researchers did compare late responders to early ones to see if there was a systematic difference in their responses. But this doesn’t by any means rule out the possibility that many students chose categorically not to respond because they had nothing to say, and therefore had no interest in the study. (Some may have even found it offensive.) These are difficulties common to this sort of simple web-based survey, and they make interpreting the results problematic enough to recommend against their use in informing policy decisions.

The biggest problems with the study, however, are not with the sample but with the methods. The survey questions appear to have been deliberately designed to generate inflated incidence rates. The basic strategy of avoiding direct questions about whether the students had been the victims of sexual assault is often justified with the assumption that many young people can’t be counted on to know what actions constitute rape and assault. But attempting to describe scenarios in survey items to get around this challenge opens the way for multiple interpretations and discounts the role of countless contextual factors. The CSA researchers write, “A surprisingly large number of respondents reported that they were at a party when the incident happened.” Cathy Young, a contributing editor at Reason magazine who analyzed the study all the way back in 2011, wrote that

the vast majority of the incidents it uncovered involved what the study termed “incapacitation” by alcohol (or, rarely, drugs): 14 percent of female respondents reported such an experience while in college, compared to six percent who reported sexual assault by physical force. Yet the question measuring incapacitation was framed ambiguously enough that it could have netted many “gray area” cases: “Has someone had sexual contact with you when you were unable to provide consent or stop what was happening because you were passed out, drugged, drunk, incapacitated, or asleep?” Does “unable to provide consent or stop” refer to actual incapacitation – given as only one option in the question – or impaired judgment? An alleged assailant would be unlikely to get a break by claiming he was unable to stop because he was drunk.

This type of confusion is why it’s important to design survey questions carefully. That the items in the CSA study failed to make the kind of fine distinctions that would allow for more conclusive interpretations suggests the researchers had other goals in mind.

The researchers’ use of the blanket term “sexual assault,” and their grouping of attempted with completed assaults, is equally suspicious. Any survey designer cognizant of all the difficulties of web surveys would likely try to narrow the focus of the study as much as possible, and they would also try to eliminate as many sources of confusion with regard to definitions or descriptions as possible. But, as Young points out,

The CSA Study’s estimate of sexual assault by physical force is somewhat problematic as well – particularly for attempted sexual assaults, which account for nearly two-thirds of the total. Women were asked if anyone had ever had or attempted to have sexual contact with them by using force or threat, defined as “someone holding you down with his or her body weight, pinning your arms, hitting or kicking you, or using or threatening to use a weapon.” Suppose that, during a make-out session, the man tries to initiate sex by rolling on top of the woman, with his weight keeping her from moving away – but once she tells him to stop, he complies. Would this count as attempted sexual assault?

The simplest way to get around many of these difficulties would have been to ask the survey participants directly whether they had experienced the category of crime the researchers were interested in. If the researchers were concerned that the students might not understand that being raped while drunk still counts as rape, why didn’t they just ask the participants a question to that effect? It’s a simple enough question to devise.

The study did pose a follow up question to participants it classified as victims of forcible assault, the responses to which hint at the students’ actual thoughts about the incidents. It turns out 37 percent of so-called forcible assault victims explained that they hadn’t contacted law enforcement because they didn’t think the incident constituted a crime. That bears repeating: a third of the students the study says were forcibly assaulted didn’t think any crime had occurred. With regard to another category of victims, those of incapacitated assault, Young writes, “Not surprisingly, three-quarters of the female students in this category did not label their experience as rape.” Of those the study classified as actually having been raped while intoxicated, only 37 percent believed they had in fact been raped. Two thirds of the women the study labels as incapacitated rape victims didn’t believe they had been raped. Why so much disagreement on such a serious issue? Of the entire incapacitated sexual assault victim category, Young writes,

Two-thirds said they did not report the incident to the authorities because they didn’t think it was serious enough. Interestingly, only two percent reported having suffered emotional or psychological injury – a figure so low that the authors felt compelled to include a footnote asserting that the actual incidence of such trauma was undoubtedly far higher.

So the largest category making up the total one-in-five statistic is predominantly composed of individuals who didn’t think what happened to them was serious enough to report. And nearly all of them came away unscathed, both physically and psychologically.

The impetus behind the CSA study was a common narrative about a so-called “rape culture” in which sexual violence is accepted as normal and young women fail to report incidents because they’re convinced you’re just supposed to tolerate it. That was the researchers’ rationale for using their own classification scheme for the survey participants’ experiences even when it was at odds with the students’ beliefs. But researchers have been doing this same dance for thirty years. As Young writes,

When the first campus rape studies in the 1980s found that many women labeled as victims by researchers did not believe they had been raped, the standard explanation was that cultural attitudes prevent women from recognizing forced sex as rape if the perpetrator is a close acquaintance. This may have been true twenty-five years ago, but it seems far less likely in our era of mandatory date rape and sexual assault workshops and prevention programs on college campuses.

The CSA also surveyed a large number of men, almost none of whom admitted to assaulting women. The researchers hypothesize that the men may have feared the survey wasn’t really anonymous, but that would mean they knew the behaviors in question were wrong. Again, if the researchers are really worried about mistaken beliefs regarding the definition of rape, they could investigate the issue with a few added survey items.

The huge discrepancies between incidences of sexual violence as measured by researchers and as reported by survey participants becomes even more suspicious in light of the history of similar studies. Those campus rape studies Young refers to from the 1980s produced a ratio of one in four. Their credibility was likewise undermined by later surveys that found that most of the supposed victims didn’t believe they’d been raped, and around forty percent of them went on to have sex with their alleged assailants again. A more recent study by the CDC used similar methods—a phone survey with a low response rate—and concluded that one in five women has been raped at some time in her life. Looking closer at this study, feminist critic and critic of feminism Christina Hoff Sommers attributes this finding as well to “a non-representative sample and vaguely worded questions.” It turns out activists have been conducting different versions of this same survey, and getting similarly, wildly inflated results for decades.

Sommers challenges the CDC findings in a video everyone concerned with the issue of sexual violence should watch. We all need to understand that well-intentioned and intelligent people can, and often do, get carried away with activism that seems to have laudable goals but ends up doing more harm than good. Some people even build entire careers on this type of crusading. And PR has become so sophisticated that we never need to let a shortage, or utter lack of evidence keep us from advocating for our favorite causes. But there’s still a fourth problem with crazily exaggerated risk assessments—they obfuscate issues of real importance, making it more difficult to come up with real solutions. As Sommers explains,

To prevent rape and sexual assault we need state-of-the-art research. We need sober estimates. False and sensationalist statistics are going to get in the way of effective policies. And unfortunately, when it comes to research on sexual violence, exaggeration and sensation are not the exception; they are the rule. If you hear about a study that shows epidemic levels of sexual violence against American women, or college students, or women in the military, I can almost guarantee the researchers used some version of the defective CDC methodology. Now by this method, known as advocacy research, you can easily manufacture a women’s crisis. But here’s the bottom line: this is madness. First of all it trivializes the horrific pain and suffering of survivors. And it sends scarce resources in the wrong direction. Sexual violence is too serious a matter for antics, for politically motivated posturing. And right now the media, politicians, rape culture activists—they are deeply invested in these exaggerated numbers.

So while more and more normal, healthy, and consensual sexual practices are considered crimes, actual acts of exploitation and violence are becoming all the more easily overlooked in the atmosphere of paranoia. And college students face the dilemma of either risking assault or accusation by going out to enjoy themselves or succumbing to the hysteria and staying home, missing out on some of the richest experiences college life has to offer.

One in five is a truly horrifying ratio. As conservative crime researcher Heather McDonald points out, “Such an assault rate would represent a crime wave unprecedented in civilized history. By comparison, the 2012 rape rate in New Orleans and its immediately surrounding parishes was .0234 percent; the rate for all violent crimes in New Orleans in 2012 was .48 percent.” I don’t know how a woman can pass a man on a sidewalk after hearing such numbers and not look at him with suspicion. Most of the reforms rape culture activists are pushing for now chip away at due process and strip away the rights of the accused. No one wants to make coming forward any more difficult for actual victims, but our first response to anyone making such a grave accusation—making any accusation—should be skepticism. Victims suffer severe psychological trauma, but then so do the falsely accused. The strongest evidence of an honest accusation is often the fact that the accuser must incur some cost in making it. That’s why we say victims who come forward are heroic. That’s the difference between a victim and a survivor.

Trumpeting crazy numbers creates the illusion that a large percentage of men are monsters, and this fosters an us-versus-them mentality that obliterates any appreciation for the difficulty of establishing guilt. That would be a truly scary world to live in. Fortunately, we in the US don’t really live in such a world. Sex doesn’t have to be that scary. It’s usually pretty damn fun. And the vast majority of men you meet—the vast majority of women as well—are good people. In fact, I’d wager most men would step in if they were around when some psychopath was trying to rape someone.

Also read:

And:

FROM DARWIN TO DR. SEUSS: DOUBLING DOWN ON THE DUMBEST APPROACH TO COMBATTING RACISM

And:

VIOLENCE IN HUMAN EVOLUTION AND POSTMODERNISM'S CAPTURE OF ANTHROPOLOGY

Lab Flies: Joshua Greene’s Moral Tribes and the Contamination of Walter White

Joshua Greene’s book “Moral Tribes” posits a dual-system theory of morality, where a quick, intuitive system 1 makes judgments based on deontological considerations—”it’s just wrong—whereas the slower, more deliberative system 2 takes time to calculate the consequences of any given choice. Audiences can see these two systems on display in the series “Breaking Bad,” as well as in critics’ and audiences’ responses.

Walter White’s Moral Math

In an episode near the end of Breaking Bad’s fourth season, the drug kingpin Gus Fring gives his meth cook Walter White an ultimatum. Walt’s brother-in-law Hank is a DEA agent who has been getting close to discovering the high-tech lab Gus has created for Walt and his partner Jesse, and Walt, despite his best efforts, hasn’t managed to put him off the trail. Gus decides that Walt himself has likewise become too big a liability, and he has found that Jesse can cook almost as well as his mentor. The only problem for Gus is that Jesse, even though he too is fed up with Walt, will refuse to cook if anything happens to his old partner. So Gus has Walt taken at gunpoint to the desert where he tells him to stay away from both the lab and Jesse. Walt, infuriated, goads Gus with the fact that he’s failed to turn Jesse against him completely, to which Gus responds, “For now,” before going on to say,

In the meantime, there’s the matter of your brother-in-law. He is a problem you promised to resolve. You have failed. Now it’s left to me to deal with him. If you try to interfere, this becomes a much simpler matter. I will kill your wife. I will kill your son. I will kill your infant daughter.

In other words, Gus tells Walt to stand by and let Hank be killed or else he will kill his wife and kids. Once he’s released, Walt immediately has his lawyer Saul Goodman place an anonymous call to the DEA to warn them that Hank is in danger. Afterward, Walt plans to pay a man to help his family escape to a new location with new, untraceable identities—but he soon discovers the money he was going to use to pay the man has already been spent (by his wife Skyler). Now it seems all five of them are doomed. This is when things get really interesting.

Walt devises an elaborate plan to convince Jesse to help him kill Gus. Jesse knows that Gus would prefer for Walt to be dead, and both Walt and Gus know that Jesse would go berserk if anyone ever tried to hurt his girlfriend’s nine-year-old son Brock. Walt’s plan is to make it look like Gus is trying to frame him for poisoning Brock with risin. The idea is that Jesse would suspect Walt of trying to kill Brock as punishment for Jesse betraying him and going to work with Gus. But Walt will convince Jesse that this is really just Gus’s ploy to trick Jesse into doing what he has forbidden Gus to do up till now—and kill Walt himself. Once Jesse concludes that it was Gus who poisoned Brock, he will understand that his new boss has to go, and he will accept Walt’s offer to help him perform the deed. Walt will then be able to get Jesse to give him the crucial information he needs about Gus to figure out a way to kill him.

It’s a brilliant plan. The one problem is that it involves poisoning a nine-year-old child. Walt comes up with an ingenious trick which allows him to use a less deadly poison while still making it look like Brock has ingested the ricin, but for the plan to work the boy has to be made deathly ill. So Walt is faced with a dilemma: if he goes through with his plan, he can save Hank, his wife, and his two kids, but to do so he has to deceive his old partner Jesse in just about the most underhanded way imaginable—and he has to make a young boy very sick by poisoning him, with the attendant risk that something will go wrong and the boy, or someone else, or everyone else, will die anyway. The math seems easy: either four people die, or one person gets sick. The option recommended by the math is greatly complicated, however, by the fact that it involves an act of violence against an innocent child.

In the end, Walt chooses to go through with his plan, and it works perfectly. In another ingenious move, though, this time on the part of the show’s writers, Walt’s deception isn’t revealed until after his plan has been successfully implemented, which makes for an unforgettable shock at the end of the season. Unfortunately, this revelation after the fact, at a time when Walt and his family are finally safe, makes it all too easy to forget what made the dilemma so difficult in the first place—and thus makes it all too easy to condemn Walt for resorting to such monstrous means to see his way through.

Fans of Breaking Bad who read about the famous thought-experiment called the footbridge dilemma in Harvard psychologist Joshua Greene’s multidisciplinary and momentously important book Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap between Us and Them will immediately recognize the conflicting feelings underlying our responses to questions about serving some greater good by committing an act of violence. Here is how Greene describes the dilemma:

A runaway trolley is headed for five railway workmen who will be killed if it proceeds on its present course. You are standing on a footbridge spanning the tracks, in between the oncoming trolley and the five people. Next to you is a railway workman wearing a large backpack. The only way to save the five people is to push this man off the footbridge and onto the tracks below. The man will die as a result, but his body and backpack will stop the trolley from reaching the others. (You can’t jump yourself because you, without a backpack, are not big enough to stop the trolley, and there’s no time to put one on.) Is it morally acceptable to save the five people by pushing this stranger to his death? (113-4)

As was the case for Walter White when he faced his child-poisoning dilemma, the math is easy: you can save five people—strangers in this case—through a single act of violence. One of the fascinating things about common responses to the footbridge dilemma, though, is that the math is all but irrelevant to most of us; no matter how many people we might save, it’s hard for us to see past the murderous deed of pushing the man off the bridge. The answer for a large majority of people faced with this dilemma, even in the case of variations which put the number of people who would be saved much higher than five, is no, pushing the stranger to his death is not morally acceptable.

Another fascinating aspect of our responses is that they change drastically with the modification of a single detail in the hypothetical scenario. In the switch dilemma, a trolley is heading for five people again, but this time you can hit a switch to shift it onto another track where there happens to be a single person who would be killed. Though the math and the underlying logic are the same—you save five people by killing one—something about pushing a person off a bridge strikes us as far worse than pulling a switch. A large majority of people say killing the one person in the switch dilemma is acceptable. To figure out which specific factors account for the different responses, Greene and his colleagues tweak various minor details of the trolley scenario before posing the dilemma to test participants. By now, so many experiments have relied on these scenarios that Greene calls trolley dilemmas the fruit flies of the emerging field known as moral psychology.

The Automatic and Manual Modes of Moral Thinking

One hypothesis for why the footbridge case strikes us as unacceptable is that it involves using a human being as an instrument, a means to an end. So Greene and his fellow trolleyologists devised a variation called the loop dilemma, which still has participants pulling a hypothetical switch, but this time the lone victim on the alternate track must stop the trolley from looping back around onto the original track. In other words, you’re still hitting the switch to save the five people, but you’re also using a human being as a trolley stop. People nonetheless tend to respond to the loop dilemma in much the same way they do the switch dilemma. So there must be some factor other than the prospect of using a person as an instrument that makes the footbridge version so objectionable to us.

Greene’s own theory for why our intuitive responses to these dilemmas are so different begins with what Daniel Kahneman, one of the founders of behavioral economics, labeled the two-system model of the mind. The first system, a sort of autopilot, is the one we operate in most of the time. We only use the second system when doing things that require conscious effort, like multiplying 26 by 47. While system one is quick and intuitive, system two is slow and demanding. Greene proposes as an analogy the automatic and manual settings on a camera. System one is point-and-click; system two, though more flexible, requires several calibrations and adjustments. We usually only engage our manual systems when faced with circumstances that are either completely new or particularly challenging.