READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

I am Jack’s Raging Insomnia: The Tragically Overlooked Moral Dilemma at the Heart of Fight Club

There’s a lot of weird theorizing about what the movie Fight Club is really about and why so many men find it appealing. The answer is actually pretty simple: the narrator can’t sleep because his job has him doing something he knows is wrong, but he’s so emasculated by his consumerist obsessions that he won’t risk confronting his boss and losing his job. He needs someone to teach him to man up, so he creates Tyler Durden. Then Tyler gets out of control.

Image by Canva’s Magic Media

[This essay is a brief distillation of ideas explored in much greater depth in Hierarchies in Hell and Leaderless Fight Clubs: Altruism, Narrative Interest, and the Adaptive Appeal of Bad Boys, my master’s thesis]

If you were to ask one of the millions of guys who love the movie Fight Club what the story is about, his answer would most likely emphasize the violence. He might say something like, “It’s about men returning to their primal nature and getting carried away when they find out how good it feels.” Actually, this is an answer I would expect from a guy with exceptional insight. A majority would probably just say it’s about a bunch of guys who get together to beat the crap out of each other and pull a bunch pranks. Some might remember all the talk about IKEA and other consumerist products. Our insightful guy may even connect the dots and explain that consumerism somehow made the characters in the movie feel emasculated, and so they had to resort to fighting and vandalism to reassert their manhood. But, aside from ensuring they would know what a duvet is—“It’s a fucking blanket”—what is it exactly about shopping for household décor and modern conveniences that makes men less manly?

Maybe Fight Club is just supposed to be fun, with all the violence, and the weird sex scene with Marla, and all the crazy mischief the guys get into, but also with a few interesting monologues and voiceovers to hint at deeper meanings. And of course there’s Tyler Durden—fearless, clever, charismatic, and did you see those shredded abs? Not only does he not take shit from anyone, he gets a whole army to follow his lead, loyal to the death. On the other hand, there’s no shortage of characters like this in movies, and if that’s all men liked about Fight Club they wouldn’t sit through all the plane flights, support groups, and soap-making. It just may be that, despite the rarity of fans who can articulate what they are, the movie actually does have profound and important resonances.

If you recall, the Edward Norton character, whom I’ll call Jack (following the convention of the script), decides that his story should begin with the advent of his insomnia. He goes to the doctor but is told nothing is wrong with him. His first night’s sleep comes only after he goes to a support group and meets Bob, he of the “bitch tits,” and cries a smiley face onto his t-shirt. But along comes Marla who like Jack is visiting support groups but is not in fact recovering, sick, or dying. She is another tourist. As long as she's around, he can’t cry, and so he can’t sleep. Soon after Jack and Marla make a deal to divide the group meetings and avoid each other, Tyler Durden shows up and we’re on our way to Fight Clubs and Project Mayhem. Now, why the hell would we accept these bizarre premises and continue watching the movie unless at some level Jack’s difficulties, as well as their solutions, make sense to us?

So why exactly was it that Jack couldn’t sleep at night? The simple answer, the one that Tyler gives later in the movie, is that he’s unhappy with his life. He hates his job. Something about his “filing cabinet” apartment rankles him. And he’s alone. Jack’s job is to fly all over the country to investigate accidents involving his company’s vehicles and to apply “the formula.” I’m going to quote from Chuck Palahniuk’s book:

You take the population of vehicles in the field (A) and multiply it by the probable rate of failure (B), then multiply the result by the average cost of an out-of-court settlement (C).

A times B times C equals X. This is what it will cost if we don’t initiate a recall.

If X is greater than the cost of a recall, we recall the cars and no one gets hurt.

If X is less than the cost of a recall, then we don’t recall (30).

Palahniuk's inspiration for Jack's job was an actual case involving the Ford Pinto. What this means is that Jack goes around trying to protect his company's bottom line to the detriment of people who drive his company's cars. You can imagine the husband or wife or child or parent of one of these accident victims hearing about this job and asking Jack, "How do you sleep at night?"

Going to support groups makes life seem pointless, short, and horrible. Ultimately, we all have little control over our fates, so there's no good reason to take responsibility for anything. When Jack burst into tears as Bob pulls his face into his enlarged breasts, he's relinquishing all accountability; he's, in a sense, becoming a child again. Accordingly, he's able to sleep like a baby. When Marla shows up, not only is he forced to confront the fact that he's healthy and perfectly able to behave responsibly, but he is also provided with an incentive to grow up because, as his fatuous grin informs us, he likes her. And, even though the support groups eventually fail to assuage his guilt, they do inspire him with the idea of hitting bottom, losing all control, losing all hope.

Here’s the crucial point: If Jack didn't have to worry about losing his apartment, or losing all his IKEA products, or losing his job, or falling out of favor with his boss, well, then he would be free to confront that same boss and tell him what he really thinks of the operation that has supported and enriched them both. Enter Tyler Durden, who systematically turns all these conditionals into realities. In game theory terms, Jack is both a 1st order and a 2nd order free rider because he both gains at the expense of others and knowingly allows others to gain in the same way. He carries on like this because he's more motivated by comfort and safety than he is by any assurance that he's doing right by other people.

This is where Jack being of "a generation of men raised by women" becomes important (50). Fathers and mothers tend to treat children differently. A study that functions well symbolically in this context examined the ways moms and dads tend to hold their babies in pools. Moms hold them facing themselves. Dads hold them facing away. Think of the way Bob's embrace of Jack changes between the support group and the fight club. When picked up by moms, babies breathing and heart-rates slow. Just the opposite happens when dads pick them up--they get excited. And if you inventory the types of interactions that go on between the two parents it's easy to see why.

Not only do dads engage children in more rough-and-tumble play; they are also far more likely to encourage children to take risks. In one study, fathers told they'd have to observe their child climbing a slope from a distance making any kind of rescue impossible in the event of a fall set the slopes at a much steeper angle than mothers in the same setup.

Fight Club isn't about dominance or triumphalism or white males' reaction to losing control; it's about men learning that they can't really live if they're always playing it safe. Jack actually says at one point that winning or losing doesn't much matter. Indeed, one of the homework assignments Tyler gives everyone is to start a fight and lose. The point is to be willing to risk a fight when it's necessary--i.e. when someone attempts to exploit or seduce you based on the assumption that you'll always act according to your rational self-interest.

And the disturbing truth is that we are all lulled into hypocrisy and moral complacency by the allures of consumerism. We may not be "recall campaign coordinators" like Jack. But do we know or care where our food comes from? Do we know or care how our soap is made? Do we bother to ask why Disney movies are so devoid of the gross mechanics of life? We would do just about anything for comfort and safety. And that is precisely how material goods and material security have emasculated us. It's easy to imagine Jack's mother soothing him to sleep some night, saying, "Now, the best thing to do, dear, is to sit down and talk this out with your boss."

There are two scenes in Fight Club that I can't think of any other word to describe but sublime. The first is when Jack finally confronts his boss, threatening to expose the company's practices if he is not allowed to leave with full salary. At first, his boss reasons that Jack's threat is not credible, because bringing his crimes to light would hurt Jack just as much. But the key element to what game theorists call altruistic punishment is that the punisher is willing to incur risks or costs to mete out justice. Jack, having been well-fathered, as it were, by Tyler, proceeds to engage in costly signaling of his willingness to harm himself by beating himself up, literally. In game theory terms, he's being rationally irrational, making his threat credible by demonstrating he can't be counted on to pursue his own rational self-interest. The money he gets through this maneuver goes, of course, not into anything for Jack, but into Fight Club and Project Mayhem.

The second sublime scene, and for me the best in the movie, is the one in which Jack is himself punished for his complicity in the crimes of his company. How can a guy with stitches in his face and broken teeth, a guy with a chemical burn on his hand, be punished? Fittingly, he lets Tyler get them both in a car accident. At this point, Jack is in control of his life, he's no longer emasculated. And Tyler flees.

One of the confusing things about the movie is that it has two overlapping plots. The first, which I've been exploring up to this point, centers on Jack's struggle to man up and become an altruistic punisher. The second is about the danger of violent reactions to the murder machine of consumerism. The male ethic of justice through violence can all too easily morph into fascism. And so, once Jack has created this father figure and been initiated into manhood by him, he then has to reign him in--specifically, he has to keep him from killing Marla. This second plot entails what anthropologist Christopher Boehm calls a "domination episode," in which an otherwise egalitarian group gets taken over by a despot who must then be defeated. Interestingly, only Jack knows for sure how much authority Tyler has, because Tyler seemingly undermines that authority by giving contradictory orders. But by now Jack is well schooled on how to beat Tyler--pretty much the same way he beat his boss.

It's interesting to think about possible parallels between the way Fight Club ends and what happened a couple years later on 9/11. The violent reaction to the criminal excesses of consumerism and capitalism wasn't, as it actually occurred, homegrown. And it wasn't inspired by any primal notion of manhood but by religious fanaticism. Still, in the minds of the terrorists, the attacks were certainly a punishment, and there's no denying the cost to the punishers.

Also read:

WHAT MAKES "WOLF HALL" SO GREAT?

Bad Men

There’s a lot not to like about the AMC series Mad Men, but somehow I found the show riveting despite all of its myriad shortcomings. Critic Daniel Mendelsohn offered up a theory to explain the show’s appeal, that it simply inspires nostalgia for all our lost childhoods. As intriguing as I always find Mendelsohn’s writing, though, I don’t think his theory holds up.

Though I had mixed feelings about the first season of Mad Men, which I picked up at Half Price Books for a steal, I still found enormous appeal in the more drawn out experience of the series unfolding. Movies lately have been leaving me tragically unmoved, with those in the action category being far too noisy and preposterous and those in the drama one too brief to establish any significant emotional investment in the characters. In a series, though, especially those in the new style pioneered by The Sopranos which eschew efforts to wrap up their plots by the end of each episode, viewers get a chance to follow characters as they develop, and the resultant investment in them makes even the most underplayed and realistic violence among them excruciatingly riveting. So, even though I found Pete Campbell, an account executive at the ad agency Sterling Cooper, the main setting for Mad Men, annoying instead of despicable, and the treatment of what we would today call sexual harassment in the office crude, self-congratulatory, and overdone, by the time I had finished watching the first season I was eager to get my hands on the second. I’ve now seen the first four seasons.

Reading up on the show on Wikipedia, I came across a few quotes from Daniel Mendelsohn’s screed against the series, “The Mad Men Account” in the New York Review of Books, and since Mendelsohn is always fascinating even when you disagree with him I made a point of reading his review after I’d finished the fourth season. His response was similar to mine in that he found himself engrossed in the show despite himself. There’s so much hoopla. But there’s so much wrong with the show. Allow me a longish quote:

The writing is extremely weak, the plotting haphazard and often preposterous, the characterizations shallow and sometimes incoherent; its attitude toward the past is glib and its self-positioning in the present is unattractively smug; the acting is, almost without exception, bland and sometimes amateurish.

Worst of all—in a drama with aspirations to treating social and historical ‘issues’—the show is melodramatic rather than dramatic. By this I mean that it proceeds, for the most part, like a soap opera, serially (and often unbelievably) generating, and then resolving, successive personal crises (adulteries, abortions, premarital pregnancies, interracial affairs, alcoholism and drug addiction, etc.), rather than exploring, by means of believable conflicts between personality and situation, the contemporary social and cultural phenomena it regards with such fascination: sexism, misogyny, social hypocrisy, racism, the counterculture, and so forth.

I have to say Mendelsohn is right on the mark here—though I will take issue with his categorical claims about the acting—leaving us with the question of why so many of us, me and Mendelsohn included, find the show so fascinating. Reading the review I found myself wanting to applaud at several points as it captures so precisely, and even artistically, the show’s failings. And yet these failings seem to me mild annoyances marring the otherwise profound gratification I get from watching. Mendelsohn lights on an answer for how it can be good while being so bad, one that squares the circle by turning the shortcomings into strengths.

If the characters are bland, stereotypical sixties people instead of individuals, if the issues are advertised rather than dramatized, if everyone depicted is hopelessly venal while evincing a smug, smiling commitment to decorum, well it’s because the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, was born in 1965, and he’s trying to recreate the world of his parents. Mendelsohn quotes Weiner:

part of the show is trying to figure out—this sounds really ineloquent—trying to figure out what is the deal with my parents. Am I them? Because you know you are…. The truth is it’s such a trope to sit around and bash your parents. I don’t want it to be like that. They are my inspiration, let’s not pretend.

Mendelsohn’s clever solution to the Mad Men puzzle is that its appeal derives from its child’s-eye view of the period during which its enthusiasts’ parents were in their ascendancy. The characters aren’t deep because children wouldn’t have the wherewithal to appreciate their depth. The issues aren’t explored in all their complexity because children are only ever vaguely aware of them. For Mendelsohn, the most important characters are the Drapers’ daughter, Sally, and the neighbor kid, Glen, who first has a crush on Don’s wife, Betty, and then falls for Sally herself. And it turns out Glen is played by Weiner’s own son.

I admit the episodes that portrayed the Draper’s divorce struck me as poignant to the point of being slightly painful, resonating as they did with my memories of my own parents’ divorce. But that was in the ‘80’s not the 60’s. And Glen is, at least for me, one of the show’s annoyances, not by any means its main appeal. His long, unblinking stares at Betty, which Mendelsohn sees as so fraught with meaning, I can’t help finding creepy. The kid makes my skin crawl, much the way Pete Campbell does. I’m forced to consider that Mendelsohn, as astute as he is about a lot of the scenes and characters, is missing something, or getting something really wrong.

In trying to account for the show’s overwhelming appeal, I think Mendelsohn is a bit too clever. I haven’t done a survey but I’d wager the results would be pretty simple: it’s Don Draper stupid. While I agree that much of the characterization and background of the central character is overwrought and unsubtle (“meretricious,” “literally,” the reviewer jokes, assuming we all know the etymology of the word), I would suggest this only makes the question of his overwhelming attractiveness all the more fascinating. Mendelsohn finds him flat. But, at least in his review, he overlooks all the crucial scenes and instead, understandably, focuses on the lame flashbacks that supposedly explain his bad behavior.

All the characters are racist, Mendelsohn charges. But in the first scene of the first episode Don notices that the black busser clearing his table is smoking a rival brand of cigarettes—that he’s a potential new customer for his clients—and casually asks him what it would take for him to switch brands. When the manager arrives at the table to chide the busser for being so talkative, Don is as shocked as we are. I can’t recall a single scene in which Don is overtly racist.

Then there’s the relationship between Don and Peggy, which, as difficult as it is to believe for all the other characters, is never sexual. Everyone is sexist, yet in the first scene bringing together Don, Peggy, and Pete, our protagonist ends up chiding the younger man, who has been giving Peggy a fashion lesson, for being disrespectful. In season two, we see Don in an elevator with two men, one of whom is giving the raunchy details of his previous night’s conquest and doesn’t bother to pause the recounting when a woman enters. Her face registers something like terror, Don’s unmistakable disgust. “Take your hat off,” he says to the offender, and for a brief moment you wonder if the two men are going to tear into him. Then Don reaches over, unchecked, removes the man’s hat, and shoves it into his chest, rendering both men silent for the duration of the elevator ride. I hate to be one of those critics who reflexively resort to their pet theory, but my enjoyment of the scene long preceded my realization that it entailed an act of altruistic punishment.

The opening credits say it all, as we see a silhouetted man, obviously Don, walking into an office which begins to collapse, and cuts to him falling through the sky against the backdrop of skyscrapers with billboards and snappy slogans. How far will Don fall? For that matter, how far will Peggy? Their experiences oddly mirror each other, and it becomes clear that while Don barks denunciations at the other members of his creative team, he often goes out of his way to mentor Peggy. He’s the one, in fact, who recognizes her potential and promotes her from a secretary to a copywriter, a move which so confounds all the other men that they conclude he must have knocked her up.

Mendelsohn is especially disappointed in Mad Men’s portrayal, or rather its failure to portray, the plight of closeted gays. He complains that when Don witnesses Sal Romano kissing a male bellhop in a hotel on a business trip, the revelation “weirdly” “has no repercussions.” But it’s not weird at all because we experience some of Sal’s anxiety about how Don will react. On the plain home, Sal is terrified, but Don rather subtly lets him know he has nothing to worry about. Don can sympathize about having secrets. We can just imagine if one of the characters other than Don had been the one to discover Sal’s homosexuality—actually we don’t have to imagine it because it happens later.

Unlike the other characters, Don’s vices, chief among them his philandering, are timeless (except his chain-smoking) and universal. And though we can’t forgive him for what he does to Betty (another annoying character, who, like some women I’ve dated, uses the strategy of being constantly aggrieved to trick you into being nice to her, which backfires because the suggestion that your proclivities aren’t nice actually provokes you), we can’t help hoping that he’ll find a way to redeem himself. As cheesy as they are, the scenes that have Don furrowing his brow and extemporizing on what people want and how he can turn it into a marketing strategy, along with the similar ones in which he feels the weight of his crimes against others, are my favorites. His voice has the amazing quality of being authoritative and yet at the same time signaling vulnerability. This guy should be able to get it. But he’s surrounded by vipers. His job is to lie. His identity is a lie he can’t escape. How will he preserve his humanity, his soul? Or will he? These questions, and similar ones about Peggy, are what keep me watching.

Don Draper, then, is a character from a long tradition of bad boys who give contradictory signals of their moral worth. Milton inadvertently discovered how powerful these characters are when Satan turned out to be by far the most compelling character in Paradise Lost. (Byron understood why immediately.) George Lucas made a similar discovery when Han Solo stole the show from Luke Skywalker. From Tom Sawyer to Jack Sparrow and Tony Soprano (Weiner was also a writer on that show), the fascination with these guys savvy enough to get away with being bad but sensitive and compassionate enough to feel bad about it has been taking a firm grip on audiences sympathies since long before Don Draper put on his hat.

A couple final notes on the show's personal appeal for me: given my interests and education, marketing and advertising would be a natural fit for me, absent my moral compunctions about deceiving people to their detriment to enrich myself. Still, it's nice to see a show focusing on the processes behind creativity. Then there's the scene in season four in which Don realizes he's in love with his secretary because she doesn't freak out when his daughter spills her milkshake. Having spent too much of my adult life around women with short fuses, and so much of my time watching Mad Men being annoyed with Betty, I laughed until I teared up.

Also read:

SYMPATHIZING WITH PSYCHOS: WHY WE WANT TO SEE ALEX ESCAPE HIS FATE AS A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

THE ADAPTIVE APPEAL OF BAD BOYS

SABBATH SAYS: PHILIP ROTH AND THE DILEMMAS OF IDEOLOGICAL CASTRATION

Review of "Building Great Sentences," a "Great Courses" Lecture Series by Brooks Landon

Brooks Landon’s course is well worth the effort and cost, but he makes some interesting suggestions about what constitutes a great sentence. To him, greatness has to do with the structure of the language, but truly great sentences—truly great writing—gets its power from its role as a conveyance of meaning, i.e. the words’ connection to the real world.

You’ve probably received catalogues in the mail advertising “Great Courses.” I’ve been flipping through them for years thinking I should try a couple but have always been turned off by the price. Recently, I saw that they were on sale, and one in particular struck me as potentially worthwhile. “Building Great Sentences: Exploring the Writer’s Craft” is taught by Brooks Landon, who is listed as part of the faculty at the University of Iowa. It turns out, however, he’s not in any way affiliated with the august Creative Writing Workshop, and though he uses several example sentences from literature I’d say his primary audience is people interested in Rhetoric and Composition—and that makes the following criticisms a bit unfair. So let me first say that I enjoyed the lectures and think it well worth the money (about thirty bucks) and time (twenty-four half-hour-long lectures).

Landon is obviously reading from a teleprompter, and he’s standing behind a lectern in what looks like Mr. Roger’s living room decked out to look scholarly. But he manages nonetheless to be animated, enthusiastic, and engaging. He gives plenty of examples of the principles he discusses, all of which appear in text form and are easy to follow—though they do at times veer toward the eye-glazingly excessive.

The star of the show is what Landon calls “cumulative sentences,” those long developments from initial capitalized word through a series of phrases serving as free modifiers, each building on its predecessor, focusing in, panning out, or taking it as a point of departure as the writer moves forward into unexplored territory. After watching several lectures, I went to the novel I’m working on and indeed discovered more than a few instances where I’d seen fit to let my phrases accumulate into a stylistic flourish. The catch is that these instances were distantly placed from one another. Moving from my own work to some stories in the Summer Fiction Issue of The New Yorker, I found the same trend. The vast majority of sentences follow Strunk and White’s dictum to be simple and direct, a point Landon acknowledges. Still, for style and rhetorical impact, the long sentences Landon describes are certainly effective.

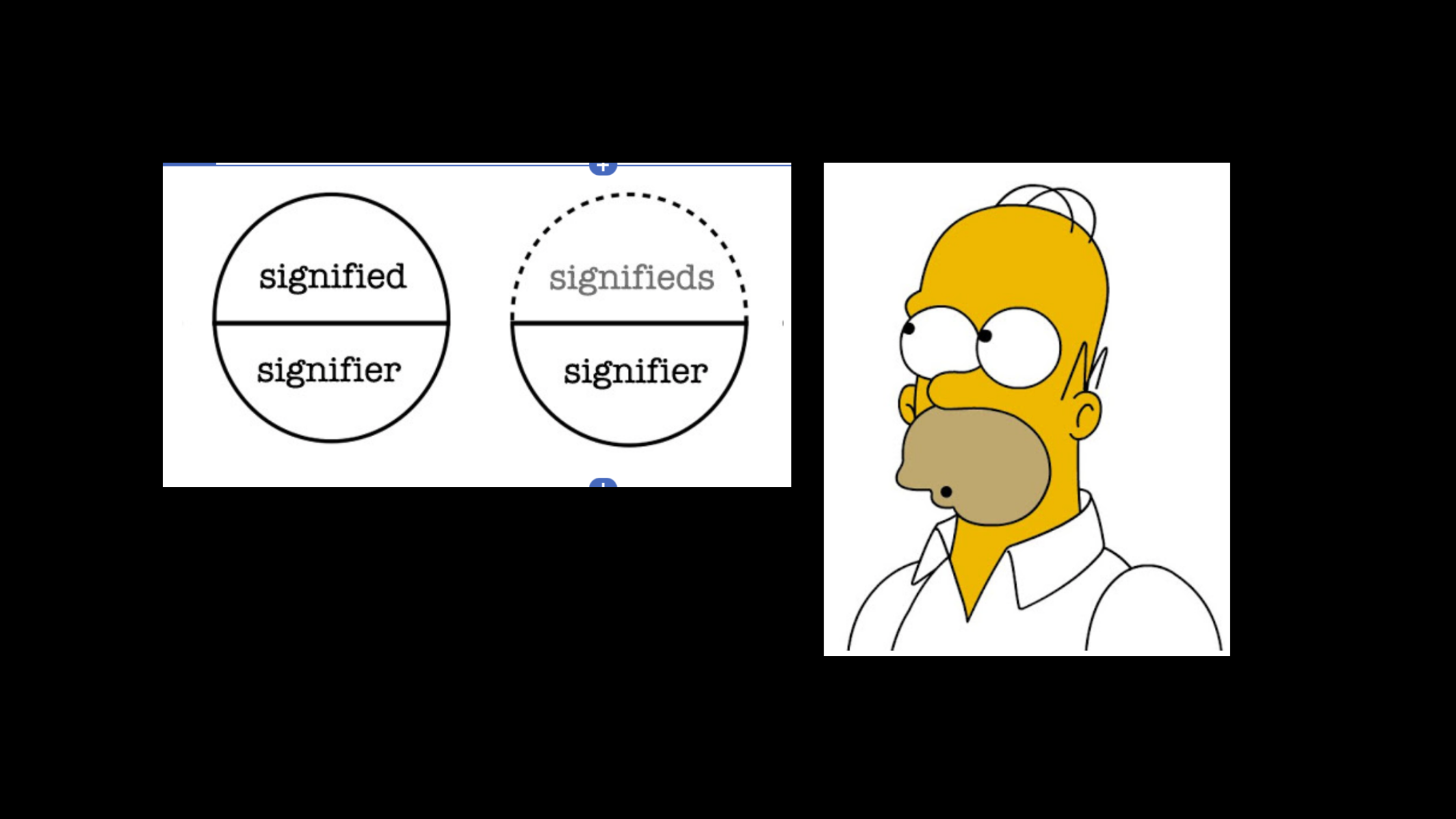

Landon and I part ways, though, when it comes to “acrobatic” sentences which “draw attention to themselves.” Giving William Gass a high seat in his pantheon of literary luminaries, Landon explains that “Gass always sees language as a subject every bit as interesting and important as is the referential world his language points to, invokes, or stands for.” While this poststructuralist sentiment seems hard to object to, it misses the point of what language does and how it works. Sentences can call attention to themselves for performing their functions well, but calling attention to themselves should never be one of their functions.

Writers like Gass and Pynchon and Wallace fail in their quixotic undertakings precisely because they perform too many acrobatics. While it is true that many readers, particularly those who appreciate literary as opposed to popular fiction—yes, there is a difference—are attuned to the pleasures of language, luxuriating in precise and lyrical writing, there’s something perverse about fixating on sentences to the exclusion of things like character. Great words in great sentences incorporating great images and suggestive comparisons can make the world in which a story takes place come alive—so much so that the life of the story escapes the page and transforms the way readers see the world beyond it. But the prompt for us to keep reading is not the promise of more transformative language; it’s the anticipation of transforming characters. Great sentences in literature owe their greatness to the moments of inspiration, from tiny observation to earth-shattering epiphany, experienced by the people at the heart of the story. Their transformations become our transformations. And literary language may seem to derive whatever greatness it achieves from precision and lyricism, but at a more fundamental level of analysis it must be recognized that writing must be precise and lyrical in its detailing of the thoughts and observations of the characters readers seek to connect with. This takes us to a set of considerations that transcend the workings of any given sentence.

Landon devotes an entire lecture to the rhythm of prose, acknowledging it must be thought of differently from meter in poetry, but failing to arrive at an adequate, objective definition. I wondered all the while why we speak about rhythm at all when we’re discussing passages that don’t follow one. Maybe the rhythm is variable. Maybe it’s somehow progressive and evolving. Or maybe we should simply find a better word to describe this inscrutable quality of impactful and engaging sentences. I propose grace. Indeed, a singer demonstrates grace by adhering to a precisely measured series of vocal steps. Noting a similar type of grace in writing, we’re tempted to hear it as rhythmical, even though its steps are in no way measured. Grace is that quality of action that leaves audiences with an overwhelming sense of its having been well-planned and deftly executed, well-planned because its deft execution appeared so effortless—but with an element of surprise just salient enough to suggest spontaneity. Grace is a delicate balance between the choreographed and the extemporized.

Grace in writing is achieved insofar as the sequential parts—words, phrases, clauses, sentences, paragraphs, sections, chapters—meet the demands of their surroundings, following one another seamlessly and coherently, performing the function of conveying meaning, in this case of connecting the narrator’s thoughts and experiences to the reader. A passage will strike us as particularly graceful when it conveys a great deal of meaning in a seemingly short chain of words, a feat frequently accomplished with analogies (a point on which Landon is eloquent), or when it conveys a complex idea or set of impressions in a way that’s easily comprehended. I suspect Landon would agree with my definition of grace. But his focus on lyrical or graceful sentences, as opposed to sympathetic or engaging characters—or any of the other aspects of literary writing—precludes him from lighting on the idea that grace can be strategically lain aside for the sake of more immediate connections with the people and events of the story, connections functioning in real-time as the reader’s eyes take in the page.

Sentences in literature like to function mimetically, though this observation goes unmentioned in the lectures. Landon cites the beautifully graceful line from Gatsby,

Slenderly, languidly, their hands set lightly on their hips the two young women preceded us out onto a rosy-colored porch open toward the sunset where four candles flickered on the table in the diminished wind (16).

The multiple L’s roll out at a slow pace, mimicking the women and the scene being described. This is indeed a great sentence. But so too is the later sentence in which Nick Carraway recalls being chagrined upon discovering the man he’s been talking to about Gatsby is in fact Gatsby himself.

Nick describes how Gatsby tried to reassure him: “He smiled understandingly—much more than understandingly.” The first notable thing about this sentence is that it stutters. Even though Nick is remembering the scene at a more comfortable future time, he re-experiences his embarrassment, and readers can’t help but sympathize. The second thing to note is that this one sentence, despite serving as a crucial step in the development of Nick’s response to meeting Gatsby and forming an impression of him, is just that, a step. The rest of the remarkable passage comes in the following sentences:

It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced—or seemed to face—the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. Precisely at that point it vanished—and I was looking at an elegant young rough-neck, a year or two over thirty, whose elaborate formality of speech just missed being absurd. Some time before he introduced himself I’d got a strong impression that he was picking his words with care (52-3).

Beginning with a solecism (“reassurance in it, that…”) that suggests Nick’s struggle to settle on the right description, moving onto another stutter (or seemed to face) which indicates his skepticism creeping in beside his appreciation of the regard, the passage then moves into one of those cumulative passages Landon so appreciates. But then there’s the jarring incongruity of the smile’s vanishing. This is, as far as I can remember, the line that sold me on the book when I first read it. You can really feel Nick’s confusion and astonishment. And the effect is brought about by sentences, an irreducible sequence of them, that are markedly ungraceful. (Dashes are wonderful for those break-ins so suggestive of spontaneity and advance in real-time.)

Also read:

Kayaking on a Wormhole

Being in a kayak on the creek, away from civilization even while you’re smack in the middle of it, works some tricky magic on your sense of time. This is my remembrance and reflection on one particular trip with a friend.

We’d been on the water for quite a while, neither of us at all sure just how much longer we’d be on it before reaching the Hursh Road Bridge, cattycorner to which, in a poorly tended gravel parking lot marking the head of a trail through a nature preserve, I’d parked Kevin's work truck before transferring vehicles to ride with him in his wife’s truck, kayaks strapped to the roof, to Cook’s Landing, another park situated in the shadow of a bridge, this one for Coldwater Road just north of Shoaf on the way to Garret. After maybe an hour of paddling and floating, it occurred to me to start attending to our banter and assessing how faithfully some of the dialogue between friends in my stories mimicked it.

“What the hell kind of bird is that?”

“Probably an early bird.”

“Probably a dirty bird.”

“Oh yeah, it’s filthy.”

At one point, after posing a series of questions about what I’d rather have fall on me from the trees—a cricket or a spider?; a spider or a centipede?; a spider or a snake?—followed by the question of what I’d do if I saw a giant snake someone had let loose slither into the water after me, he began a story about a herpetologist in Brazil: “Did you hear what happened?” Of course, I hadn’t heard; the story was from a show on cable about anacondas. This hundred and fifty pound woman was walking through the marshes, tracking a snake, which turned out to be about twenty-eight feet long and five hundred pounds, to study it.

“She’s following the track it left in the tall grass, and then she senses that there’s something watching her. When she turns around, she sees that it’s reared up”—he held up his arm with his fist bent forward—“so it’s just looking at her at eye level.”

“Did it say, ‘Who da fuck is you?’”

“Snakes don’t generally creep me out, but I don’t like the idea of it, like, following her and rearing up like that.”

“Yeah, I’ve never heard of an anaconda doing that. You hear of cobras doing it. Did she say, ‘Dere’s snakes out here dis big!?’”—my impression of Ice Cube in the movie Anaconda.

When I asked what she did, he said he didn’t remember. The snake had attacked her, lunging at her face, but she must’ve escaped somehow because she was being interviewed for the show. At a couple points in his recounting of the story, I thought how silly it was. For one thing, it’s impossible to sense something watching you. For another, her being a herpetologist doesn’t rule out the possibility that she was embellishing. And yet I couldn’t help picturing the encounter, vividly, as I paddled my kayak.

The story was oddly appropriate. Every time we put in on Cedar Creek and make it some distance from the roads, we get the sense that we’re closer to the jungle than we are to civilization. Kevin knows snakes are my fear totem. At times, scenes from the Paul Bowles collection A Delicate Prey, or from Heart of Darkness, or even from Huckleberry Finn would drift into my mind. We did briefly discuss some paleoanthropology—recent discoveries in Dmanisi, Georgia suggesting a possible origin of modern humans in Western Asia rather than Africa—but, for the most part, for the duration of our sojourn on the river, we may as well have been two prepubescent boys. Compared to the way we were talking, the dialogue between friends in my stories is far too sophisticated.

But that’s really not how we normally talk. As our time on the water accrued long past our upper estimates, and as the fallen-tree-strewn stretches got more and more tricky to traverse, that sense of being far from civilization, far from our lives, our adult lives, became ever more profound. The gnats and mosquitoes and splendidly black dragonflies, their wings tipped with blue, swarmed us whenever we lolled in the shade, getting more bold as more of our bug spray got washed away. We talked about all the ways we’d heard of that Native Americans and other indigenous peoples avoided bug bites and poison plants. The shores were lousy with poison ivy. It was easy to lose your identity. We could’ve been any two guys in the world, at any time in history. The phones were locked away in a waterproof box. The kayaks could’ve been made of anything; the plastic was adventitious. Out here, with the old-growth trees and the ghostly shadows of quickly glimpsed fish, it was the big concrete bridges and the exiguous houses and yards backing up to the creek that seemed impermanent, unreal. Even the human trash washing into the leafy and wooden detritus gathering against the smoothed-over bark of collapsed trees was being dulled and stripped of all signs of cleverness.

“Do you ever have déjà vu?” Kevin asked after we’d passed all the expected landmarks and gotten over our astonishment at how drastically we’d underestimated the length of the journey down the creek. “Because the first time we kayaked here, I was completely sure I’d had a dream about it—but I had the dream before I’d ever been here.”

“I think it’s something about the river,” I said, recalling several instances that day when I had experienced an emptying of mind, something I’ve often strived for while meditating but seldom even come to close to achieving. You find yourself being carried downstream, lulled, quieted, your gaze focused on the busy motion of countless tiny bugs on a swatch of surface gilt with sunlight. Their coordinated pattern dazzles you. It’s the only thing remotely resembling a thought. “There’s something about the motion of the water and the way it has you slowly moving along. I keep laying back and watching the undersides of the leaves move over me. It puts you in a trance. It’s hypnotic.”

“You’re right. It is, like, mesmerizing.” He knew what I was talking about, but we kept shuffling through our stock of words because none of them seemed to get it quite right.

So there we were, a couple of nameless, ageless guys floating down the river, leaning back to watch the trees slide away upstream, soft white clouds in a soft blue sky, riotous distant stars shattering the immense dark of some timeless night.

“I forgive you river for making me drag my boat through all those nettles.”

“I’ll reserve my forgiveness until I find out if I have poison ivy.”

Also read:

Taking the GRE again after 10 Years

I aced the verbal reasoning section of the GRE the first time I took it. It ended up, not being the worst thing that ever happened to me, but… distracting. Eleven years later, I had to take the test again to start trying to make my way back into school. How could I compete with my earlier perfection?

I had it timed: if I went to the bathroom at 8:25, I’d be finishing up the essay portion of the test about ten minutes after my bladder was full again. Caffeine being essential for me to get into the proper state of mind for writing, I’d woken up to three cans of Diet Mountain Dew and two and half rather large cups of coffee. I knew I might not get called in to take the test precisely at 8:30, but I figured I could handle the pressure, as it were. The clock in the office of the test center read 8:45 when I walked in. Paperwork, signatures, getting a picture taken, turning out all my pockets (where I managed to keep my three talismans concealed)—by the time I was sitting down in the carrel—in a room that might serve as a meeting place for prisoners and their lawyers—it was after 9:00. And there were still more preliminaries to go through.

Test takers are allotted 45 minutes for an essay on the “Issue Topic” prompted by a short quote. The “Analysis of an Argument” essay takes a half hour. The need to piss got urgent with about ten minutes left on the clock for the issue essay. By the end of the second essay, I was squirming and dancing and pretty desperate. Of course, I had to wait for our warden to let me out of the testing room. And then I had to halt midway through the office to come back and sign myself out. Standing at the urinal—and standing and standing—I had plenty of time to consider how poorly designed my strategy had been. I won’t find out my scores for the essay portion for ten or so days.

**********************************

I’ve been searching my apartment for the letter with my official scores from the first time I took the GRE about ten years ago. I’d taken it near the end of the summer, at one of those times in life of great intellectual awakening. With bachelor’s degrees in both anthropology and psychology, and with only the most inchoate glimmerings of a few possible plans for the future, I lived in my dad’s enormous house with my oldest brother, who had returned after graduating from Notre Dame and was now taking graduate courses at IPFW, my alma mater, and some roommates. I delivered pizzas in the convertible Mustang I bought as a sort of hand-me-down from that same brother. And I spent hours every day reading.

I’m curious about the specific date of the test because it would allow me place it in the context of what I was reading. It would also help me ascertain the amount of time I spent preparing. If memory serves, I was doing things like pouring over various books by Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Dawkins, trying to decide which one of them knew the real skinny on how evolution works. I think by then I’d read Frank Sulloway’s Born to Rebel, in which he applied complex statistics to data culled from historical samples and concluded that later-born siblings tend to be less conscientious but more open to new ideas and experiences. I was delighted to hear that the former president had read Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, and thought it tragically unimaginable that the current president would ever read anything like that. At some point, I began circling words I didn’t recognize or couldn’t define so when I was finished with the chapter I could look them up and make a few flashcards.

I’m not even sure the flashcards were in anticipation of the GRE. Several of my classmates in both the anthropology and psychology departments had spoken to me by then of their dejection upon receiving their scores. I was scared to take it. The trend seemed to be that everyone was getting about a hundred points less on this test than they did on the SAT. I decided I only really cared about the verbal reasoning section, and a 620 on that really wasn’t acceptable. Beyond the flashcards, I got my hands on a Kaplan CD-ROM from a guy at school and started doing all the practice tests on it. The scores it gave me hovered in the mid-600s. It also gave me scads of unfamiliar words (like scad) to put in my stack of flashcards, which grew, ridiculously, to the height of about a foot.

I don’t remember much about the test itself. It was at a Sylvan Learning Center that closed a while back. One of the reading comprehension excerpts was on chimpanzees, which I saw as a good sign. When I was done, there was a screen giving me a chance to admit I cheated. It struck me as odd. Then came the screen with my scores—800 verbal reasoning. I looked around the room and saw nothing but the backs of silent test-takers. Could this be right? I never ace anything. It sank in when I was sitting down in the Mustang. Driving home on I-69, I sang along to “The Crush” by Dave Matthews, elated.

I got accepted into MIT’s program in science writing based on that score and a writing sample in which I defended Frank Sulloway’s birth order theory against Judith Rich Harris, the author of The Nurture Assumption, another great book. But Harris’s arguments struck me as petty and somewhat disgraceful. She was engaging in something akin to a political campaign against a competing theory, rather than making a good faith effort to discover the truth. Anyway, the article I wrote got long and unwieldy. Michael Shermer considered it for publication in Skeptic but ultimately declined because I just didn’t have my chops up when it came to writing about science. By then, I was a writer of fiction.

That’s why upon discovering how expensive a year in Cambridge would be and how little financial aid I’d be getting I declined MIT's invitation to attend their program. If being a science writer was my dream, I’d have gone. But I decided to hold out for an acceptance to an MFA program in creative writing. I’d already applied two years in row before stretching my net to include science writing. But the year I got accepted at MIT ended up being the third year of summary rejection on the fiction front. I had one more year before that perfect GRE score expired.

**********

Year four went the same way all the other years had gone. I was in my late twenties now and had the feeling whatever opportunities that were once open to me had slipped away. Next came a crazy job at a restaurant—Lucky’s—and a tumultuous relationship with the kitchen manager. After I had to move out of the apartment I shared with her in the wake of our second breakup (there would be a third), I was in a pretty bad place. But I made the smartest decision I’d made in a while and went back to school to get my master’s in English at IPFW.

The plan was to improve my qualifications for creative writing programs. And now that I’m nearly finished with the program I put re-taking the GRE at the top of my list for things to do this summer. In the middle of May, I registered to take it on June 22nd. I’d been dreading it ever since my original score expired, but now I was really worried. What would it mean if I didn’t get an 800 again? What if I got significantly lower than that? The MFA programs I’ll be applying to are insanely competitive: between five hundred and a thousand applicants for less than a dozen spaces. At the same time, though, there was a sense that a lower score would serve as this perfect symbol for just how far I’d let my life go off-track.

Without much conscious awareness of what I was doing, I started playing out a Rocky narrative, or some story like Mohammed Ali making his comeback after losing his boxing license for refusing to serve in Vietnam. I would prove I wasn’t a has-been, that whatever meager accomplishments I had under my belt weren’t flukes. Last semester I wrote a paper on how to practice to be creative, and one of the books I read for it was K. Anders Ericsson’s The Road to Excellence. So, after signing up for the test I created a regimen of what Ericsson calls “deliberate practice,” based on anticipation and immediate feedback. I got my hands on as many sample items and sample tests I could find. I made little flashcards with the correct answers on them to make the feedback as close as possible to the hazarded answer. I put hours and hours into it. And I came up with a strategy for each section, and for every possible contingency I could think of. I was going to beat the GRE, again, through sheer force of will.

***********

The order of the sections is variable. Ideally, the verbal section would have come first after the essay section so I wouldn’t have to budget my stores of concentration. But sitting down again after relieving my bladder I saw the quantitative section appear before me on the screen. Oh well, I planned for this too, I thought. I adhered pretty well to my strategy of working for a certain length of time to see if I could get the answer and then guessing if it didn’t look promising. And I achieved my goal for this section by not embarrassing myself. I got a 650.

The trouble began almost immediately when the verbal questions starting coming. The strategy for doing analogies, the questions I most often missed in practice, was to work out the connection between the top words, “the bridge,” before considering the five word couples below to see which one has the same bridge. But because the screen was so large, and because I was still jittery from the caffeine, I couldn’t read the first word pair without seeing all the others. I abandoned the strategy with the first question.

Then disaster struck. I’d anticipated only two sets of reading comprehension questions, but then, with the five minute warning already having passed, another impossibly long blurb appeared. I resign myself at that point to having to give up my perfect score. I said to myself, “Just read it quick and give the best answers you can.” I finished the section with about twenty seconds left. At least all the antonyms had been easy. Next came an experimental section I agreed to take since I didn’t need to worry about flagging concentration anymore. For the entire eighteen minutes it took, I sat there feeling completely defeated. I doubt my answers for that section will be of much use.

Finally, I was asked if I wanted to abandon my scores—a ploy, I’m sure to get skittish people to pay to take the test twice. I said no, and clicked to see and record my scores. There it was at the top of the screen, my 800. I’d visualized the moment several times. I was to raise one arm in victory—but I couldn’t because the warden would just think I was raising my hand to signal I needed something. I also couldn’t because I didn’t feel victorious. I still felt defeated. I was sure all the preparation I’d done had been completely pointless. I hadn’t boxed. I’d clenched my jaw, bunched up my fist, and brawled.

I listened to “The Crush” on the way home again, but as I detoured around all the construction downtown I wasn’t in a celebratory mood. I wasn’t elated. I was disturbed. The experience hadn’t been at all like a Rocky movie. It was a lot more like Gattaca. I’d come in, had my finger pricked so they could read my DNA, and had the verdict delivered to me. Any score could have come up on the screen. I had no control over it. That it turned out to be the one I was after was just an accident. A fluke.

**************

The week before I took the test, I’d met a woman at Columbia Street who used to teach seventh graders. After telling her I taught Intro Comp at IPFW, we discussed how teaching is a process of translation from how you understand something into a language that will allow others who lack your experience and knowledge to understand it. Then you have to add some element of entertainment so you don’t lose their attention. The younger the students, the more patience it takes to teach them. Beginning when I was an undergrad working in the Writing Center, but really picking up pace as I got more and more experience as a TA, the delight I used to feel in regard to my own cleverness was being superseded by the nagging doubt that I could ever pass along the method behind it to anyone.

When you’re young (or conservative), it’s easy to look at people who don’t do as well as you with disdain, as if it’s a moral failing on their part. You hold the conviction deep in your gut that if they merely did what you’ve done they’d have what you have or know what you know. Teaching disabuses you of this conviction (which might be why so many teachers are liberal). How many times did I sit with a sharp kid in the writing center trying to explain some element of college writing to him or her, trying to think back to how I had figured it out, and realizing either that I’d simply understood it without much effort or arrived at an understanding through a process that had already failed this kid? You might expect such a realization would make someone feel really brilliant. But in fact it’s humbling. You wonder how many things there are, fascinating things, important things, that despite your own best effort you’ll never really get. Someone, for instance, probably “just gets” how to relay complex information to freshman writers—just gets teaching.

And if, despite your efforts, you’re simply accorded a faculty for perceiving this or understanding that, if you ever lose it your prospects for recreating the same magic are dismal. What can be given can be taken away. Finally, there’s the question of desert. That I can score an 800 on the verbal reasoning section of the GRE is not tied to my effort or to my will. I like to read, always have. It’s not work to me. My proficiency is morally arbitrary. And yet everyone will say about my accomplishments and accolades, “You deserve it.”

Really, though, this unsettled feeling notwithstanding, this is some stupid shit to complain about. I aced the GRE—again. It’s time to celebrate.

Also read:

Art as Altruism: Lily Briscoe and the Ghost of Mrs. Ramsay in To the Lighthouse Part 1 of 2

Woolf’s struggle with her mother, and its manifestation as Lily’s struggle with Mrs. Ramsay, represents a sort of trial in which the younger living woman defends herself against a charge of selfishness leveled by her deceased elder. And since Woolf’s obsession with her mother ceased upon completion of the novel, she must have been satisfied that she had successfully exonerated herself.

Virginia Woolf underwent a transformation in the process of writing To the Lighthouse the nature of which has been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. At the center of the novel is the relationship between the beautiful, self-sacrificing, and yet officious Mrs. Ramsay, and the retiring, introverted artist Lily Briscoe. “I wrote the book very quickly,” Woolf recalls in “Sketch of the Past,” “and when it was written, I ceased to be obsessed by my mother. I no longer hear her voice; I do not see her.” Quoting these lines, biographer Hermione Lee suggests the novel is all about Woolf’s parents, “a way of pacifying their ghosts” (476). But how exactly did writing the novel function to end Woolf’s obsession with her mother? And, for that matter, why would she, at forty-four, still be obsessed with a woman who had died when she was only thirteen? Evolutionary psychologist Jesse Bering suggests that while humans are uniquely capable of imagining the inner workings of each other’s minds, the cognitive mechanisms underlying this capacity, which psychologists call “theory of mind,” simply fail to comprehend the utter extinction of those other minds. However, the lingering presence of the dead is not merely a byproduct of humans’ need to understand and communicate with other living humans. Bering argues that the watchful gaze of disembodied minds—real or imagined—serves a type of police function, ensuring that otherwise selfish and sneaky individuals cooperate and play by the rules of society. From this perspective, Woolf’s struggle with her mother, and its manifestation as Lily’s struggle with Mrs. Ramsay, represents a sort of trial in which the younger living woman defends herself against a charge of selfishness leveled by her deceased elder. And since Woolf’s obsession with her mother ceased upon completion of the novel, she must have been satisfied that she had successfully exonerated herself.

Woolf made no secret of the fact that Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay were fictionalized versions of her own parents, and most critics see Lily as a stand-in for the author—even though she is merely a friend of the Ramsay family. These complex relationships between author and character, and between daughter and parents, lie at the heart of a dynamic which readily lends itself to psychoanalytic explorations. Jane Lilienfeld, for instance, suggests Woolf created Lily as a proxy to help her accept her parents, both long dead by the time she began writing, “as monumental but flawed human beings,” whom she both adored and detested. Having reduced the grand, archetypal Mrs. Ramsay to her proper human dimensions, Lily is free to acknowledge her own “validity as a single woman, as an artist whose power comes not from manipulating others’ lives in order to fulfill herself, but one whose mature vision encapsulates and transcends reality” (372). But for all the elaborate dealings with mythical and mysterious psychic forces, the theories of Freud and Jung explain very little about why writers write and why readers read. And they explain very little about how people relate to the dead, or about what role the dead play in narrative. Freud may have been right about humans’ intense ambivalence toward their parents, but why should this tension persist long after those parents have ceased to exist? And Jung may have been correct in his detection of mythic resonances in his patients’ dreams, but what accounts for such universal narrative patterns? What do they explain?

Looking at narrative from the perspective of modern evolutionary biology offers several important insights into why people devote so much time and energy to, and get so much gratification from immersing themselves in the plights and dealings of fictional characters. Anthropologists believe the primary concern for our species at the time of its origin was the threat of rival tribes vying for control of limited resources. The legacy of this threat is the persistent proclivity for tribal—us versus them—thinking among modern humans. But alongside our penchant for dehumanizing members of out-groups arose a set of mechanisms designed to encourage—and when necessary to enforce—in-group cooperation for the sake of out-competing less cohesive tribes. Evolutionary literary theorist William Flesch sees in narrative a play of these cooperation-enhancing mechanisms. He writes, “our capacity for narrative developed as a way for us to keep track of cooperators” (67), and he goes on to suggest we tend to align ourselves with those we perceive as especially cooperative or altruistic while feeling an intense desire to see those who demonstrate selfishness get their comeuppance. This is because “altruism could not sustain an evolutionarily stable system without the contribution of altruistic punishers to punish the free-riders who would flourish in a population of purely benevolent altruists” (66). Flesch cites the findings of numerous experiments which demonstrate people’s willingness to punish those they see as exploiting unspoken social compacts and implicit rules of fair dealing, even when meting out that punishment involves costs or risks to the punisher (31-34). Child psychologist Karen Wynn has found that even infants too young to speak prefer to play with puppets or blocks with crude plastic eyes that have in some way demonstrated their altruism over the ones they have seen behaving selfishly or aggressively (557-560). Such experiments lead Flesch to posit a social monitoring and volunteered affect theory of narrative interest, whereby humans track the behavior of others, even fictional others, in order to assess their propensity for altruism or selfishness and are anxious to see that the altruistic are vindicated while the selfish are punished. In responding thus to other people’s behavior, whether they are fictional or real, the individual signals his or her own propensity for second- or third-order altruism.

The plot of To the Lighthouse is unlike anything else in literature, and yet a great deal of information is provided regarding the relative cooperativeness of each of the characters. Foremost among them in her compassion for others is Mrs. Ramsay. While it is true from the perspective of her own genetic interests that her heroic devotion to her husband and their eight children can be considered selfish, she nonetheless extends her care beyond the sphere of her family. She even concerns herself with the tribulations of complete strangers, something readers discover early in the novel, as

she ruminated the other problem, of rich and poor, and the things she saw with her own eyes… when she visited this widow, or that struggling wife in person with a bag on her arm, and a note- book and pencil with which she wrote down in columns carefully ruled for the purpose wages and spendings, employment and unemployment, in the hope that thus she would cease to be a private woman whose charity was half a sop to her own indignation, half relief to her own curiosity, and become what with her untrained mind she greatly admired, an investigator, elucidating the social problem. (9)

No sooner does she finish reflecting on this social problem than she catches sight of her husband’s friend Charles Tansley, who is feeling bored and “out of things,” because no one staying at the Ramsays’ summer house likes him. Regardless of the topic Tansley discusses with them, “until he had turned the whole thing around and made it somehow reflect himself and disparage them—he was not satisfied” (8). And yet Mrs. Ramsay feels compelled to invite him along on an errand so that he does not have to be alone. Before leaving the premises, though, she has to ask yet another houseguest, Augustus Carmichael, “if he wanted anything” (10). She shows this type of exquisite sensitivity to others’ feelings and states of mind throughout the first section of the novel.

Mrs. Ramsay’s feelings about Lily, another houseguest, are at once dismissive and solicitous. Readers are introduced to Lily only through Mrs. Ramsay’s sudden realization, after prolonged absentmindedness, that she is supposed to be holding still so Lily can paint her. Mrs. Ramsay’s son James, who is sitting with her as he cuts pictures out of a catalogue, makes a strange noise she worries might embarrass him. She turns to see if anyone has heard: “Only Lily Briscoe, she was glad to find; and that did not matter.” Mrs. Ramsay is doing Lily the favor of posing, but the gesture goes no further than mere politeness. Still, there is a quality the younger woman possesses that she admires. “With her little Chinese eyes,” Mrs. Ramsay thinks, “and her puckered-up face, she would never marry; one could not take her painting very seriously; she was an independent little creature, and Mrs. Ramsay liked her for it” (17). Lily’s feelings toward her hostess, on the other hand, though based on a similar recognition that the other enjoys aspects of life utterly foreign to her, are much more intense. At one point early in the novel, Lily wonders, “what could one say to her?” The answer she hazards is “I’m in love with you?” But she decides that is not true and settles on, “‘I’m in love with this all,’ waving her hand at the hedge, at the house, at the children” (19). What Lily loves, and what she tries to capture in her painting, is the essence of the family life Mrs. Ramsay represents, the life Lily herself has rejected in pursuit of her art. It must be noted too that, though Mrs. Ramsay is not related to Lily, Lily has only an elderly father, and so some of the appeal of the large, intact Ramsay family to Lily is the fact that she has been sometime without a mother.

Apart from admiring in the other what each lacks herself, the two women share little in common. The tension between them derives from Lily’s having resigned herself to life without a husband, life in the service of her art and caring for her father, while Mrs. Ramsay simply cannot imagine how any woman could be content without a family. Underlying this conviction is Mrs. Ramsay’s unique view of men and her relationship to them:

Indeed, she had the whole of the other sex under her protection; for reasons she could not explain, for their chivalry and valour, for the fact that they negotiated treaties, ruled India, controlled finance; finally for an attitude towards herself which no woman could fail to feel or to find agreeable, something trustful, childlike, reverential; which an old woman could take from a young man without loss of dignity, and woe betide the girl—pray Heaven it was none of her daughters!—who did not feel the worth of it, and all that it implied, to the marrow of her bones! (6)

In other words, woe betide Lily Briscoe. Anthropologists Peter Richerson and Robert Boyd, whose work on the evolution of cooperation in humans provides the foundation for Flesch’s theory of narrative, put forth the idea that culture functions to simultaneously maintain group cohesion and to help the group adapt to whatever environment it inhabits. “Human cultures,” they point out, “can change even more quickly than the most rapid examples of genetic evolution by natural selection” (43). What underlies the divergence of views about women’s roles between the two women in Woolf’s novel is that their culture is undergoing major transformations owing to political and economic upheaval in the lead-up to The First World War.

Lily has no long-established tradition of women artists in which to find solace and guidance; rather, the most salient model of womanhood is the family-minded, self-sacrificing Mrs. Ramsay. It is therefore to Mrs. Ramsay that Lily must justify her attempt at establishing a new tradition. She reads the older woman as making the implicit claim that “an unmarried woman has missed the best of life.” In response, Lily imagines how

gathering a desperate courage she would urge her own exemption from the universal law; plead for it; she liked to be alone; she liked to be herself; she was not made for that; and so have to meet a serious stare from eyes of unparalleled depth, and confront Mrs. Ramsay’s simple certainty… that her dear Lily, her little Brisk, was a fool. (50)

Living alone, being herself, and refusing to give up her time or her being to any husband or children strikes even Lily herself as both selfish and illegitimate, lacking cultural sanction and therefore doubly selfish. Trying to figure out the basis of her attraction to Mrs. Ramsay, beyond her obvious beauty, Lily asks herself, “did she lock up within her some secret which certainly Lily Briscoe believed people must have for the world to go on at all? Every one could not be as helter skelter, hand to mouth as she was” (50). Lily’s dilemma is that she can either be herself, or she can be a member of a family, because being a member of a family means she cannot be wholly herself; like Mrs. Ramsay, she would have to make compromises, and her art would cease to have any more significance than the older woman’s note-book with all its writing devoted to social problems. But she must justify devoting her life only to herself. Meanwhile, she’s desperate for some form of human connection beyond the casual greetings and formal exchanges that take place under the Ramsays’ roof.

Lily expresses a desire not just for knowledge from Mrs. Ramsay but for actual unity with her because what she needs is “nothing that could be written in any language known to men.” She wants to be intimate with the “knowledge and wisdom… stored up in Mrs. Ramsay’s heart,” not any factual information that could be channeled through print. The metaphor Lily uses for her struggle is particularly striking for anyone who studies human evolution.

How then, she had asked herself, did one know one thing or another thing about people, sealed as they were? Only like a bee, drawn by some sweetness or sharpness in the air intangible to touch or taste, one haunted the dome-shaped hive, ranged the wastes of the air over the countries of the world alone, and then haunted the hives with their murmurs and their stirrings; the hives, which were people. (51)

According to evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson, bees are one of only about fifteen species of social insect that have crossed the “Cooperation Divide,” beyond which natural selection at the level of the group supercedes selection at the level of the individual. “Social insect colonies qualify as organisms,” Wilson writes, “not because they are physically bounded but because their members coordinate their activities in organ-like fashion to perpetuate the whole” (144). The main element that separates humans from their ancestors and other primates, he argues, “is that we are evolution’s newest transition from groups of organisms to groups as organisms. Our social groups are the primate equivalent of bodies and beehives” (154). The secret locked away from Lily in Mrs. Ramsay’s heart, the essence of the Ramsay family that she loves so intensely and feels compelled to capture in her painting, is that human individuals are adapted to life in groups of other humans who together represent a type of unitary body. In trying to live by herself and for herself, Lily is going not only against the cultural traditions of the previous generation but even against her own nature.

How to Read Stories--You're probably doing it wrong

Your efforts to place each part into the context of the whole will, over time, as you read more stories, give you a finer appreciation for the strategies writers use to construct their work, one scene or one section at a time. And as you try to anticipate the parts to come from the parts you’ve read you will be training your mind to notice patterns, laying down templates for how to accomplish the types of effects—surprise, emotional resonance, lyricism, profundity—the author has accomplished.

There are whole books out there about how to read like a professor or a writer, or how to speed-read and still remember every word. For the most part, you can discard all of them. Studies have shown speed readers are frauds—the faster they read the less they comprehend and remember. The professors suggest applying the wacky theories they use to write their scholarly articles, theories which serve to cast readers out of the story into some abstract realm of symbols, psychological forces, or politics. I find the endeavor offensive.

Writers writing about how to read like a writer are operating on good faith. They just tend to be a bit deluded. Literature is very much like a magic trick, but of course it’s not real magic. They like to encourage people to stand in awe of great works and great passages—something I frankly don’t need any encouragement to do (what is it about the end of “Mr. Sammler’s Planet”?) But to get to those mystical passages you have to read a lot of workaday prose, even in the work of the most lyrical and crafty writers. Awe simply can’t be used as a reading strategy.

Good fiction is like a magic trick because it’s constructed of small parts that our minds can’t help responding to holistically. We read a few lines and all the sudden we have a person in mind; after a few pages we find ourselves caring about what happens to this person. Writers often avoid talking about the trick and the methods and strategies that go into it because they’re afraid once the mystery is gone the trick will cease to convince. But even good magicians will tell you well performed routines frequently astonish even the one performing them. Focusing on the parts does not diminish appreciation for the whole.

The way to read a piece of fiction is to use the information you've already read in order to anticipate what will happen next. Most contemporary stories are divided into several sections, which offer readers the opportunity to pause after each, reflecting how it may fit into the whole of the work. The author had a purpose in including each section: furthering the plot, revealing the character’s personality, developing a theme, or playing with perspective. Practice posing the questions to yourself at the end of each section, what has the author just done, and what does it suggests she’ll likely do in sections to come.

In the early sections, questions will probably be general: What type of story is this? What type of characters are these? But by the time you reach about the two/thirds point they will be much more specific: What’s the author going to do with this character? How is this tension going to be resolved? Efforts to classify and anticipate the elements of the story will, if nothing else, lead to greater engagement with it. Every new character should be memorized—even if doing so requires a mnemonic (practice coming up with one on the fly).

The larger goal, though, is a better understanding of how the type of fiction you read works. Your efforts to place each part into the context of the whole will, over time, as you read more stories, give you a finer appreciation for the strategies writers use to construct their work, one scene or one section at a time. And as you try to anticipate the parts to come from the parts you’ve read you will be training your mind to notice patterns, laying down templates for how to accomplish the types of effects—surprise, emotional resonance, lyricism, profundity—the author has accomplished.

By trying to get ahead of the author, as it were, you won’t be learning to simply reproduce the same effects. By internalizing the strategies, making them automatic, you’ll be freeing up your conscious mind for new flights of creative re-working. You’ll be using the more skilled author’s work to bootstrap your own skill level. But once you’ve accomplished this there’ll be nothing stopping you from taking your own writing to the next level. Anticipation makes reading a challenge in real time—like a video game. And games can be conquered.

Finally, if a story moves you strongly, re-read it immediately. And then put it in a stack for future re-reading.

Also read:

PUTTING DOWN THE PEN: HOW SCHOOL TEACHES US THE WORST POSSIBLE WAY TO READ LITERATURE

Productivity as Practice: An Expert Performance Approach to Creative Writing Pedagogy Part 1

Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson’s central finding in his research on expert achievement is that what separates those who attain a merely sufficient level of proficiency in a performance domain from those who reach higher levels of excellence is the amount of time devoted over the course of training to deliberate practice. But, in a domain with criteria for success that can only be abstractly defined, like creative writing, what would constitute deliberate practice is difficult to define.

Much of the pedagogy in creative writing workshops derives solely from tradition and rests on the assumption that the mind of the talented writer will adopt its own learned practices in the process of writing. The difficult question of whether mastery, or even expertise, can be inculcated through any process of instruction, and the long-standing tradition of assuming the answer is an only somewhat qualified “no”, comprise just one of several impediments to developing an empirically supported set of teaching methods for aspiring writers. Even the phrase, “empirically supported,” conjures for many the specter of formula, which they fear students will be encouraged to apply to their writing, robbing the products of some mysterious and ineffable quality of freshness and spontaneity. Since the criterion of originality is only one of several that are much easier to recognize than they are to define, the biggest hindrance to moving traditional workshop pedagogy onto firmer empirical ground may be the intractability of the question of what evaluative standards should be applied to student writing. Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson’s central finding in his research on expert achievement is that what separates those who attain a merely sufficient level of proficiency in a performance domain from those who reach higher levels of excellence is the amount of time devoted over the course of training to deliberate practice. But, in a domain with criteria for success that can only be abstractly defined, like creative writing, what would constitute deliberate practice is as difficult to describe in any detail as the standards by which work in that domain are evaluated.

Paul Kezle, in a review article whose title, “What Creative Writing Pedagogy Might Be,” promises more than the conclusions deliver, writes, “The Iowa Workshop model originally laid out by Paul Engle stands as the pillar of origination for all debate about creative writing pedagogy” (127). This model, which Kezle describes as one of “top-down apprenticeship,” involves a published author who’s achieved some level of acclaim—usually commensurate to the prestige of the school housing the program—whose teaching method consists of little more than moderating evaluative class discussions on each student’s work in turn. The appeal of this method is two-fold. As Shirley Geok-lin Lim explains, it “reliev[es] the teacher of the necessity to offer teacher feedback to students’ writing, through editing, commentary, and other one-to-one, labor intensive, authority-based evaluation” (81), leaving the teacher more time to write his or her own work as the students essentially teach each other and, hopefully, themselves. This aspect of self-teaching is the second main appeal of the workshop method—it bypasses the pesky issue of whether creative writing can be taught, letting the gates of the sacred citadel of creative talent remain closed. Furthermore, as is made inescapably clear in Mark McGurl’s book The Program Era, which tracks the burgeoning of creative writing programs as their numbers go from less than eighty in 1975 to nearly nine hundred today, the method works, at least in terms of its own proliferation.

But what, beyond enrolling in a workshop, can a writer do to get better at writing? The answer to this question, assuming it can be reliably applied to other writers, holds the key to answering the question of what creative writing teachers can do to help their students improve. Lim, along with many other scholars and teachers with backgrounds in composition, suggests that pedagogy needs to get beyond “lore,” by which she means “the ad hoc strategies composing what today is widely accepted as standard workshop technique” (79). Unfortunately, the direction these theorists take is forbiddingly abstruse, focusing on issues of gender and ethnic identity in the classroom, or the negotiation of power roles (see Russel 109 for a review.) Their prescription for creative writing pedagogy boils down to an injunction to introduce students to poststructuralist ways of thinking and writing. An example sentence from Lim will suffice to show why implementing this approach would be impractical: