READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

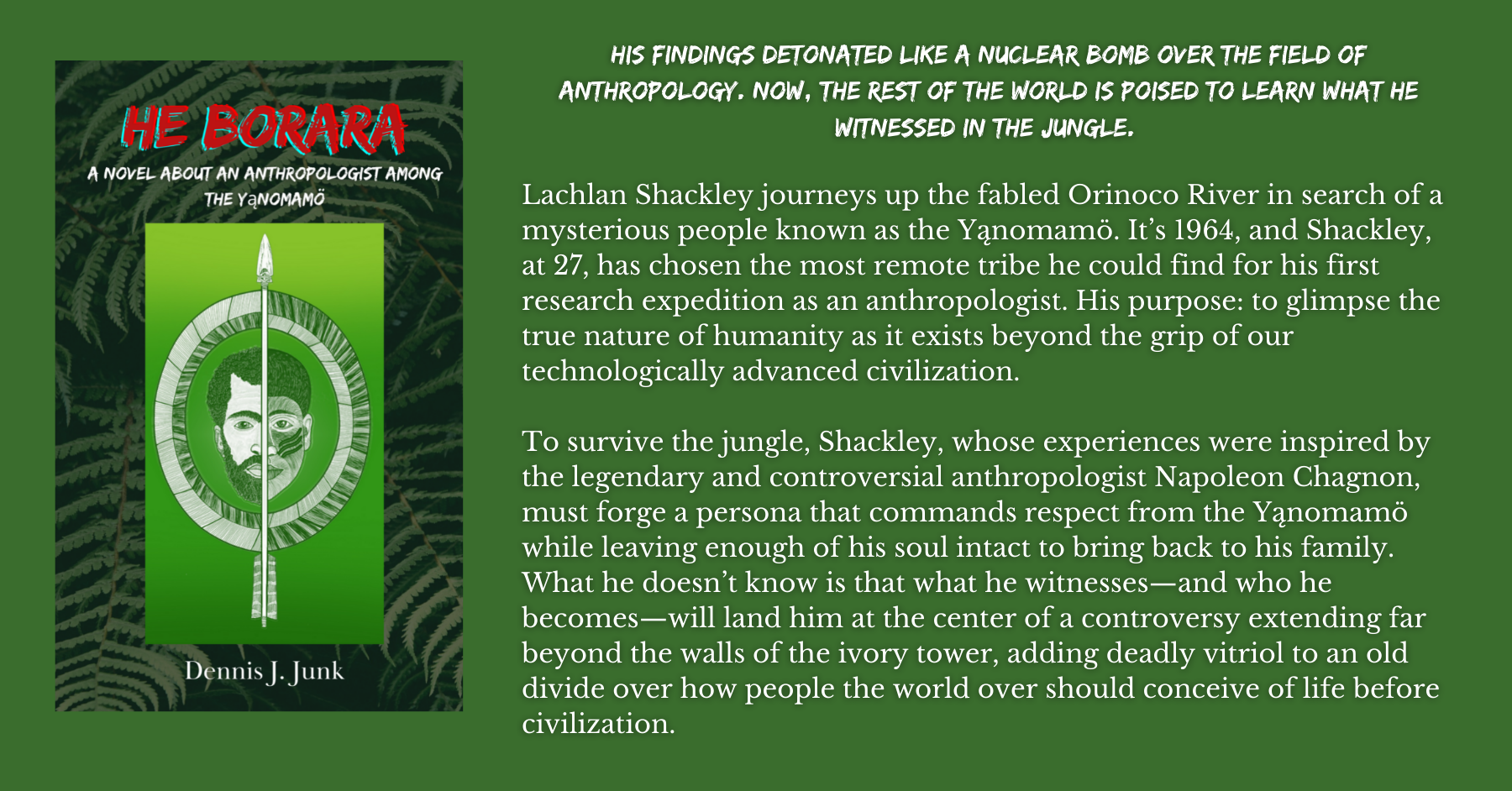

Nice Guys with Nothing to Say: Brett Martin’s Difficulty with “Difficult Men” and the Failure of Arts Scholarship

Brett Martin’s book “Difficult Men” contains fascinating sections about the history and politics behind some of our favorite shows. But whenever he reaches for deeper insights about the shows’ appeal, the results range from utterly banal to unwittingly comical. The reason for his failure is his reliance on politically motivated theorizing, which is all too fashionable in academia.

With his book Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution: From “The Sopranos” and “The Wire” to “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad”, Brett Martin shows that you can apply the whole repertoire of analytic tools furnished by contemporary scholarship in the arts to a cultural phenomenon without arriving at anything even remotely approaching an insight. Which isn’t to say the book isn’t worth reading: if you’re interested in the backstories of how cable TV series underwent their transformation to higher production quality, film-grade acting and directing, greater realism, and multiple, intricately interlocking plotlines, along with all the gossip surrounding the creators and stars, then you’ll be delighted to discover how good Martin is at delivering the dish.

He had excellent access to some of the showrunners, seems to know everything about the ones he didn’t have access to anyway, and has a keen sense for the watershed moments in shows—as when Tony Soprano snuck away from scouting out a college with his daughter Meadow to murder a man, unceremoniously, with a smile on his face, despite the fears of HBO executives that audiences would turn against the lead character for doing so. And Difficult Men is in no way a difficult read. Martin’s prose is clever without calling too much attention to itself. His knowledge of history and pop culture rivals that of anyone in the current cohort of hipster sophisticates. And his enthusiasm for the topic radiates off the pages while not marring his objectivity with fanboyism. But if you’re more interested in the broader phenomenon of unforgivable male characters audiences can’t help loving you’ll have to look elsewhere for any substantive discussion of it.

Difficult Men would have benefited from Martin being a more difficult man himself. Instead, he seems at several points to be apologizing on behalf of the show creators and their creations, simultaneously ecstatic at the unfettering of artistic freedom and skittish whenever bumping up against questions about what the resulting shows are reflecting about artists and audiences alike. He celebrates the shows’ shucking off of political correctness even as he goes out of his way to brandish his own PC bona fides. With regard to his book’s focus on men, for instance, he writes,

Though a handful of women play hugely influential roles in this narrative—as writers, actors, producers, and executives—there aren’t enough of them. Not only were the most important shows of the era run by men, they were also largely about manhood—in particular the contours of male power and the infinite varieties of male combat. Why that was had something to do with a cultural landscape still awash in postfeminist dislocation and confusion about exactly what being a man meant. (13)

Martin throws multiple explanations at the centrality of “male combat” in high-end series, but the basic fact that he suggests accounts for the prevalence of this theme across so many shows in TV’s Third Golden Age is that most of the artists working on the shows are afflicted with the same preoccupations.

In other words, middle-aged men predominated because middle-aged men had the power to create them. And certainly the autocratic power of the showrunner-auteur scratches a peculiarly masculine itch. (13)

Never mind that women make up a substantial portion of the viewership. If it ever occurred to Martin that this alleged “masculine itch” may have something to do with why men outnumber women in high-stakes competitive fields like TV scriptwriting, he knew better than to put the suspicion in writing.

The centrality of dominant and volatile male characters in America’s latest creative efflorescence is in many ways a repudiation of the premises underlying the scholarship of the decades leading up to it. With women moving into the workplace after the Second World War, and with the rise of feminism in the 1970s, the stage was set for an experiment in how malleable human culture really was with regard to gender roles. How much change did society’s tastes undergo in the latter half of the twentieth century? Despite his emphasis on “postfeminist dislocation” as a factor in the appeal of TV’s latest crop of bad boys, Martin is savvy enough to appreciate these characters’ long pedigree, up to a point. He writes of Tony Soprano, for instance,

In his self-absorption, his horniness, his alternating cruelty and regret, his gnawing unease, Tony was, give or take Prozac and one or two murders, a direct descendant of Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom. In other words, the American Everyman. (84)

According to the rules of modern criticism, it’s okay to trace creative influences along their historical lineages. And Martin is quite good at situating the Third Golden Age in its historical and technological context:

The ambition and achievement of these shows went beyond the simple notion of “television getting good.” The open-ended, twelve- or thirteen-episode serialized drama was maturing into its own, distinct art form. What’s more, it had become the signature American art form of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the equivalent of what the films of Scorsese, Altman, Coppola, and others had been to the 1970s or the novels of Updike, Roth, and Mailer had been to the 1960s. (11)

What you’re not allowed to do, however—and what Martin knows better than to try to get away with—is notice that all those male filmmakers and novelists of the 60s and 70s were dealing with the same themes as the male showrunners Martin is covering. Is this pre-feminist dislocation? Mad Men could’ve featured Don Draper reading Rabbit, Run right after it was published in 1960. In fact, Don bears nearly as much resemblance to the main character of what was arguably the first novel ever written, The Tale of Genji, by the eleventh-century Japanese noblewoman, Murasaki Shikibu, as Tony Soprano bears to Rabbit Angstrom.

Missed connections, tautologies, and non sequiturs abound whenever Martin attempts to account for the resonance of a particular theme or show, and at points his groping after insight is downright embarrassing. Difficult Men, as good as it is on history and the politicking of TV executives, can serve as a case study in the utter banality and logical bankruptcy of scholarly approaches to discussing the arts. These politically and academically sanctioned approaches can be summed up concisely, without scanting any important nuances, in the space of paragraph. While any proposed theory about average gender differences with biological bases must be strenuously and vociferously criticized and dismissed (and its proponents demonized without concern for fairness), any posited connection between a popular theme and contemporary social or political issues is seen not just as acceptable but as automatically plausible, to the point where after drawing the connection the writer need provide no further evidence whatsoever.

One of several explanations Martin throws out for the appeal of characters like Tony Soprano and Don Draper, for instance, is that they helped liberal HBO and AMC subscribers cope with having a president like George W. Bush in office. “This was the ascendant Right being presented to the disempowered Left—as if to reassure it that those in charge were still recognizably human” (87). But most of Mad Men’s run, and Breaking Bad’s too, has been under a President Obama. This doesn’t present a problem for Martin’s analysis, though, because there’s always something going on in the world that can be said to resonate with a show’s central themes. Of Breaking Bad, he writes,

Like The Sopranos, too, it uncannily anticipated a national mood soon to be intensified by current events—in this case the great economic unsettlement of the late aughts, which would leave many previously secure middle-class Americans suddenly feeling like desperate outlaws in their own suburbs. (272)

If this strikes you as comically facile, I can assure you that were the discussion taking place in the context of an explanation proposed by a social scientist, writers like Martin would be falling all over themselves trying to be the first to explain the danger of conflating correlation with causation, whether the scientist actually made that mistake or not.

But arts scholarship isn’t limited to this type of socio-historical loose association because at some point you simply can’t avoid bringing individual artists, characters, and behind-the-scenes players into the discussion. Even when it comes to a specific person or character’s motivation, though, it’s important to focus on upbringing in a given family and sociopolitical climate as opposed to any general trend in human psychology. This willful blindness becomes most problematic when Martin tries to identify commonalities shared by all the leading men in the shows he’s discussing. He writes, for example,

All of them strove, awkwardly at times, for connection, occasionally finding it in glimpses and fragments, but as often getting blocked by their own vanities, their fears, and their accumulated past crimes. (189-90)

This is the closest Martin comes to a valid insight into difficult men in the entire book. The problem is that the rule against recognizing trends in human nature has made him blind to the applicability of this observation to pretty much everyone in the world. You could use this passage as a cold read and convince people you’re a psychic.

So far, our summation of contemporary arts scholarship includes a rule against referring to human nature and an injunction to focus instead on sociopolitical factors, no matter how implausible their putative influence. But the allowance for social forces playing a role in upbringing provides something of a backdoor for a certain understanding of human nature to enter the discussion. Although the academic versions of this minimalist psychology are byzantine to the point of incomprehensibility, most of the main precepts will be familiar to you from movie and book reviews and criticism: parents, whom we both love and hate, affect nearly every aspect of our adult personalities; every category of desire, interest, or relationship is a manifestation of the sex drive; and we all have subconscious desires—all sexual in one way or another—based largely on forgotten family dramas that we enjoy seeing played out and given expression in art. That’s it.

So, if we’re discussing Breaking Bad for instance, a critic might refer to Walt and Jesse’s relationship as either oedipal, meaning they’re playing the roles of father and son who love but want to kill each other, or homoerotic, meaning their partnership substitutes for the homosexual relationship they’d both really prefer. The special attention the show gives to the blue meth and all the machines and gadgets used to make it constitutes a fetish. And the appeal of the show is that all of us in the audience wish we could do everything Walt does. Since we must repress those desires, we come to the show because watching it effects a type of release.

Not a single element of this theory has any scientific validity. If we were such horny devils, we could just as easily watch internet pornography as tune into Mad Men. Psychoanalysis is to modern scientific psychology what alchemy is to chemistry and what astrology is to astronomy. But the biggest weakness of Freud’s pseudo-theories from a scientific perspective is probably what has made them so attractive to scholars in the humanities over the past century: they don’t lend themselves to testable predictions, so they can easily be applied to a variety of outcomes. As explanations, they can never fail or be definitively refuted—but that’s because they don’t really explain anything. Quoting Craig Wright, a writer for Six Feet Under, Martin writes that

…the left always articulates a critique through the arts. “But the funny part is that masked by, or nested within, that critique is a kind of helpless eroticization of the power of the Right. They’re still in love with Big Daddy, even though they hate him.”

That was certainly true for the women who made Tony Soprano an unlikely sex symbol—and for the men who found him no less seductive. Wish fulfillment has always been at the queasy heart of the mobster genre, the longing for a life outside the bounds of convention, mingled with the conflicted desire to see the perpetrator punished for the same transgression… Likewise for viewers, for whom a life of taking, killing, and sleeping with whomever and whatever one wants had an undeniable, if conflict-laden, appeal. (88)

So Tony reminds us of W. because they’re both powerful figures, and we’re interested in powerful figures because they remind us of our dads and because we eroticize power. Even if this were true, would it contribute anything to our understanding or enjoyment of the show? Are any of these characters really that much like your own dad? Tony smashes some poor guy’s head because he got in his way, and sometimes we wish we could do that. Don Draper sleeps with lots of attractive women, and all the men watching the show would like to do that too. Startling revelations, those.

What a scholar in search of substantive insights might focus on instead is the universality of the struggle to reconcile selfish desires—sex, status, money, comfort—with the needs and well-being of the groups to which we belong. Don Draper wants to sleep around, but he also genuinely wants Betty and their children to be happy. Tony Soprano wants to be feared and respected, but he doesn’t want his daughter to think he’s a murderous thug. Walter White wants to prove he can provide for his family, but he also wants Skyler and Walter Junior to be safe. These tradeoffs and dilemmas—not the difficult men themselves—are what most distinguish these shows from conventional TV dramas. In most movies and shows, the protagonist may have some selfish desires that compete with his or her more altruistic or communal instincts, but which side ultimately wins out is a foregone conclusion. “Heroes are much better suited for the movies,” Martin quotes Alan Ball saying. “I’m more interested in real people. And real people are fucked up” (106).

Ball is the showrunner behind the HBO series Six Feet Under and True Blood, and though Martin gives him quite a bit of space in Difficult Men he doesn’t seem to notice that Ball’s “feminine style” (102) of showrunning undermines his theory about domineering characters being direct reflections of their domineering creators. The handful of interesting observations about what makes for a good series in Martin’s book is pretty evenly divvied up between Ball and David Simon, the creator of The Wire. Recalling his response to the episode of The Sopranos in which Tony strangles a rat while visiting a college campus with Meadow, Ball says,

I felt like was watching a movie from the seventies. Where it was like, “You know those cartoon ideas of good and evil? Well, forget them. We’re going to address something that’s really real.” The performances were electric. The writing was spectacular. But it was the moral complexity, the complexity of the characters and their dilemmas, that made it incredibly exciting. (94-5)

The connection between us and the characters isn’t just that we have some of the same impulses and desires; it’s that we have to do similar balancing acts as we face similar dilemmas. No, we don’t have to figure out how to whack a guy without our daughters finding out, but a lot of us probably do want to shield our kids from some of the ugliness of our jobs. And most of us have to prioritize career advancement against family obligations in one way or another. What makes for compelling drama isn’t our rooting for a character who knows what’s right and does it—that’s not drama at all. What pulls us into these shows is the process the characters go through of deciding which of their competing desires or obligations they should act on. If we see them do the wrong thing once in a while, well, that just ups the ante for the scenes when doing the right thing really counts.

On the one hand, parents and sponsors want a show that has a good message, a guy with the right ideas and virtuous motives confronted with people with bad ideas and villainous motives. The good guy wins and the lesson is conveyed to the comfortable audiences. On the other hand, writers, for the most part, want to dispense with this idea of lessons and focus on characters with murderous, adulterous, or self-aggrandizing impulses, allowing for the possibility that they’ll sometimes succumb to them. But sometimes writers face the dilemma of having something they really want to say with their stories. Martin describes David Simon’s struggle to square this circle.

As late as 2012, he would complain in a New York Times interview that fans were still talking about their favorite characters rather than concentrating on the show’s political message… The real miracle of The Wire is that, with only a few late exceptions, it overcame the proud pedantry of its creators to become one of the greatest literary accomplishments of the early twenty-first century. (135)

But then it’s Simon himself who Martin quotes to explain how having a message to convey can get in the way of a good story.

Everybody, if they’re trying to say something, if they have a point to make, they can be a little dangerous if they’re left alone. Somebody has to be standing behind them saying, dramatically, “Can we do it this way?” When the guy is making the argument about what he’s trying to say, you need somebody else saying, “Yeah, but…” (207)

The exploration of this tension makes up the most substantive and compelling section of Difficult Men.

Unfortunately, Martin fails to contribute anything to this discussion of drama and dilemmas beyond these short passages and quotes. And at several points he forgets his own observation about drama not being reducible to any underlying message. The most disappointing part of Difficult Men is the chapter devoted to Vince Gilligan and his show Breaking Bad. Gilligan is another counterexample to the theory that domineering and volatile men in the writer’s seat account for domineering and volatile characters in the shows; the writing room he runs gives the chapter its name, “The Happiest Room in Hollywood.” Martin writes that Breaking Bad is “arguably the best show on TV, in many ways the culmination of everything the Third Golden Age had made possible” (264). In trying to explain why the show is so good, he claims that

…whereas the antiheroes of those earlier series were at least arguably the victims of their circumstances—family, society, addiction, and so on—Walter White was insistently, unambiguously, an agent with free will. His journey became a grotesque magnification of the American ethos of self-actualization, Oprah Winfrey’s exhortation that all must find and “live your best life.” What if, Breaking Bad asked, one’s best life happened to be as a ruthless drug lord? (268)

This is Martin making the very mistake he warns against earlier in the book by finding some fundamental message at the core of the show. (Though he could simply believe that even though it’s a bad idea for writers to try to convey messages it’s okay for critics to read them into the shows.) But he’s doing the best he can with the tools of scholarship he’s allowed to marshal. This assessment is an extension of his point about post-feminist dislocation, turning the entire series into a slap in the face to Oprah, that great fount of male angst.

To point out that Martin is perfectly wrong about Walter White isn’t merely to offer a rival interpretation. Until the end of season four, as any reasonable viewer who’s paid a modicum of attention to the development of his character will attest, Walter is far more at the mercy of circumstances than any of the other antiheroes in the Third Golden Age lineup. Here’s Walter explaining why he doesn’t want to undergo an expensive experimental cancer treatment in season one:

What I want—what I need—is a choice. Sometimes I feel like I never actually make any of my own. Choices, I mean. My entire life, it just seems I never, you know, had a real say about any of it. With this last one—cancer—all I have left is how I choose to approach this.

He’s secretly cooking meth to make money for his family already at this point, but that’s a lot more him making the most of a bad situation than being the captain of his own fate. Can you imagine Tony or Don saying anything like this? Even when Walt delivers his famous “I am the danger” speech in season four—which gets my vote for the best moment in TV history (or film history too for that matter)—the statement is purely aspirational; he’s still in all kinds of danger at that point. Did Martin neglect the first four seasons and pick up watching only after Walt finally killed Gus? Either way, it’s a big, embarrassing mistake.

The dilemmas Walt faces are what make his story so compelling. He’s far more powerless than other bad boy characters at the start of the series, and he’s also far more altruistic in his motives. That’s precisely why it’s so disturbing—and riveting—to see those motives corrupted by his gradually accumulating power. It’s hard not to think of the cartel drug lords we always hear about in Mexico according to those “cartoon ideas of good and evil” Alan Ball was so delighted to see smashed by Tony Soprano. But Breaking Bad goes a long way toward bridging the divide between such villains and a type of life we have no trouble imagining. The show isn’t about free will or self-actualization at all; it’s about how even the nicest guy can be turned into one of the scariest villains by being placed in a not all that far-fetched set of circumstances. In much the same way, Martin, clearly a smart guy and a talented writer, can be made to look like a bit of an idiot by being forced to rely on a bunch of really bad ideas as he explores the inner workings some really great shows.

If men’s selfish desires—sex, status, money, freedom—aren’t any more powerful than women’s, their approaches to satisfying them still tend to be more direct, less subtle. But what makes it harder for a woman’s struggles with her own desires to take on the same urgency as a man’s is probably not that far removed from the reasons women are seldom as physically imposing as men. Volatility in a large man can be really frightening. Men are more likely to have high-status careers like Don’s still today, but they’re also far more likely to end up in prison. These are pretty high stakes. And Don’s actions have ramifications for not just his own family’s well-being, but that of everyone at Sterling Cooper and their families, which is a consequence of that high-status. So status works as a proxy for size. Carmela Soprano’s volatility could be frightening too, but she isn’t the time-bomb Tony is. Speaking of bombs, Skyler White is an expert at bullying men, but going head-to-head with Walter she’s way overmatched. Men will always be scarier than women on average, so their struggles to rein in their scarier impulses will seem more urgent. Still, the Third Golden Age is a teenager now, and as anxious as I am to see what happens to Walter White and all his friends and family, I think the bad boy thing is getting a little stale. Anyone seen Damages?

Also read:

The Criminal Sublime: Walter White's Brutally Plausible Journey to the Heart of Darkness in Breaking Bad

and:

And:

SABBATH SAYS: PHILIP ROTH AND THE DILEMMAS OF IDEOLOGICAL CASTRATION

Sabbath Says: Philip Roth and the Dilemmas of Ideological Castration

With “Sabbath’s Theater,” Philip Roth has called down the thunder. The story does away with the concept of a likable character while delivering a wildly absorbing experience. And it satirizes all the woeful facets of how literature is taught today.

Sabbath’s Theater is the type of book you lose friends over. Mickey Sabbath, the adulterous title character who follows in the long literary line of defiantly self-destructive, excruciatingly vulnerable, and offputtingly but eloquently lustful leading males like Holden Caulfield and Humbert Humbert, strains the moral bounds of fiction and compels us to contemplate the nature of our own voyeuristic impulse to see him through to the end of the story—and not only contemplate it but defend it, as if in admitting we enjoy the book, find its irreverences amusing, and think that in spite of how repulsive he often is there still might be something to be said for poor old Sabbath we’re confessing to no minor offense of our own. Fans and admiring critics alike can’t resist rushing to qualify their acclaim by insisting they don’t condone his cheating on both of his wives, the seduction of a handful of his students, his habit of casually violating others’ privacy, his theft, his betrayal of his lone friend, his manipulations, his racism, his caustic, often cruelly precise provocations—but by the time they get to the end of Sabbath’s debt column it’s a near certainty any list of mitigating considerations will fall short of getting him out of the red. Sabbath, once a puppeteer who now suffers crippling arthritis, doesn’t seem like a very sympathetic character, and yet we sympathize with him nonetheless. In his wanton disregard for his own reputation and his embrace, principled in a way, of his own appetites, intuitions, and human nastiness, he inspires a fascination none of the literary nice guys can compete with. So much for the argument that the novel is a morally edifying art form.

Thus, in Sabbath, Philip Roth has created a character both convincing and compelling who challenges a fundamental—we may even say natural—assumption about readers’ (or viewers’) role in relation to fictional protagonists, one made by everyone from the snarky authors of even the least sophisticated Amazon.com reviews to the theoreticians behind the most highfalutin academic criticism—the assumption that characters in fiction serve as vehicles for some message the author created them to convey, or which some chimerical mechanism within the “dominant culture” created to serve as agents of its own proliferation. The corollary is that the task of audience members is to try to decipher what the author is trying to say with the work, or what element of the culture is striving to perpetuate itself through it. If you happen to like the message the story conveys, or agree with it at some level, then you recommend the book and thus endorse the statement. Only rarely does a reviewer realize or acknowledge that the purpose of fiction is not simply to encourage readers to behave as the protagonists behave or, if the tale is a cautionary one, to expect the same undesirable consequences should they choose to behave similarly. Sabbath does in fact suffer quite a bit over the course of the novel, and much of that suffering comes as a result of his multifarious offenses, so a case can be made on behalf of Roth’s morality. Still, we must wonder if he really needed to write a story in which the cheating husband is abandoned by both of his wives to make the message sink in that adultery is wrong—especially since Sabbath doesn’t come anywhere near to learning that lesson himself. “All the great thoughts he had not reached,” Sabbath muses in the final pages, “were beyond enumeration; there was no bottom to what he did not have to say about the meaning of his life” (779).

Part of the reason we can’t help falling back on the notions that fiction serves a straightforward didactic purpose and that characters should be taken as models, positive or negative, for moral behavior is that our moral emotions are invariably and automatically engaged by stories; indeed, what we usually mean when we say we got into a story is that we were in suspense as we anticipated whether the characters ultimately met with the fates we felt they deserved. We reflexively size up any character the author introduces the same way we assess the character of a person we’re meeting for the first time in real life. For many readers, the question of whether a novel is any good is interchangeable with the question of whether they liked the main characters, assuming they fare reasonably well in the culmination of the plot. If an author like Roth evinces an attitude drastically different from ours toward a character of his own creation like Sabbath, then we feel that in failing to condemn him, in holding him up as a model, the author is just as culpable as his character. In a recent edition of PBS’s American Masters devoted to Roth, for example, Jonathan Franzen, a novelist himself, describes how even he couldn’t resist responding to his great forebear’s work in just this way. “As a young writer,” Franzen recalls, “I had this kind of moralistic response of ‘Oh, you bad person, Philip Roth’” (54:56).

That fiction’s charge is to strengthen our preset convictions through a process of narrative tempering, thus catering to our desire for an orderly calculus of just deserts, serves as the basis for a contract between storytellers and audiences, a kind of promise on which most commercial fiction delivers with a bang. And how many of us have wanted to throw a book out of the window when we felt that promise had been broken? The goal of professional and academic critics, we may imagine, might be to ease their charges into an appreciation of more complex narrative scenarios enacted by characters who escape easy categorization. But since scholarship in the humanities, and in literary criticism especially, has been in a century-long sulk over the greater success of science and the greater renown of scientists, professors of literature have scarcely even begun to ponder what anything resembling a valid answer to the questions of how fiction works and what the best strategies for experiencing it might look like. Those who aren’t pouting in a corner about the ascendancy of science—but the Holocaust!—are stuck in the muck of the century-old pseudoscience of psychoanalysis. But the real travesty is that the most popular, politically inspired schools of literary criticism—feminism, Marxism, postcolonialism—actively preach the need to ignore, neglect, and deny the very existence of moral complexity in literature, violently displacing any appreciation of difficult dilemmas with crudely tribal formulations of good and evil.

For those inculcated with a need to take a political stance with regard to fiction, the only important dynamics in stories involve the interplay of society’s privileged oppressors and their marginalized victims. In 1976, nearly twenty years before the publication of Sabbath’s Theater, the feminist critic Vivian Gornick lumped Roth together with Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer in an essay asking “Why Do These Men Hate Women?” because she took issue with the way women are portrayed in their novels. Gornick, following the methods standard to academic criticism, doesn’t bother devoting any space in her essay to inconvenient questions about how much we can glean about these authors from their fictional works or what it means that the case for her prosecution rests by necessity on a highly selective approach to quoting from those works. And this slapdash approach to scholarship is supposedly justified because she and her fellow feminist critics believe women are in desperate need of protection from the incalculable harm they assume must follow from such allegedly negative portrayals. In this concern for how women, or minorities, or some other victims are portrayed and how they’re treated by their notional oppressors—rich white guys—Gornick and other critics who make of literature a battleground for their political activism are making the same assumption about fiction’s straightforward didacticism as the most unschooled consumers of commercial pulp. The only difference is that the academics believe the message received by audiences is all that’s important, not the message intended by the author. The basis of this belief probably boils down to its obvious convenience.

In Sabbath’s Theater, the idea that literature, or art of any kind, is reducible to so many simple messages, and that these messages must be measured against political agendas, is dashed in the most spectacularly gratifying fashion. Unfortunately, the idea is so seldom scrutinized, and the political agendas are insisted on so inclemently, clung to and broadcast with such indignant and prosecutorial zeal, that it seems not one of the critics, nor any of the authors, who were seduced by Sabbath were able to fully reckon with the implications of that seduction. Franzen, for instance, in a New Yorker article about fictional anti-heroes, dodges the issue as he puzzles over the phenomenon that “Mickey Sabbath may be a disgustingly self-involved old goat,” but he’s somehow still sympathetic. The explanation Franzen lights on is that

the alchemical agent by which fiction transmutes my secret envy or my ordinary dislike of “bad” people into sympathy is desire. Apparently, all a novelist has to do is give a character a powerful desire (to rise socially, to get away with murder) and I, as a reader, become helpless not to make that desire my own. (63)

If Franzen is right—and this chestnut is a staple of fiction workshops—then the political activists are justified in their urgency. For if we’re powerless to resist adopting the protagonist’s desires as our own, however fleetingly, then any impulse to victimize women or minorities must invade readers’ psyches at some level, conscious or otherwise. The simple fact, however, is that Sabbath has not one powerful desire but many competing desires, ones that shift as the novel progresses, and it’s seldom clear even to Sabbath himself what those desires are. (And is he really as self-involved as Franzen suggests? It seems to me rather that he compulsively tries to get into other people’s heads, reflexively imagining elaborate stories for them.)

While we undeniably respond to virtuous characters in fiction by feeling anxiety on their behalf as we read about or watch them undergo the ordeals of the plot, and we just as undeniably enjoy seeing virtue rewarded alongside cruelty being punished—the goodies prevailing over the baddies—these natural responses do not necessarily imply that stories compel our interest and engage our emotions by providing us with models and messages of virtue. Stories aren’t sermons. In his interview for American Masters, Roth explained what a writer’s role is vis-à-vis social issues.

My job isn’t to be enraged. My job is what Chekhov said the job of an artist was, which is the proper presentation of the problem. The obligation of the writer is not to provide the solution to a problem. That’s the obligation of a legislator, a leader, a crusader, a revolutionary, a warrior, and so on. That’s not the goal or aim of a writer. You’re not selling it, and you’re not inviting condemnation. You’re inviting understanding. (59:41)

The crucial but overlooked distinction that characters like Sabbath—but none so well as Sabbath—bring into stark relief is the one between declarative knowledge on the one hand and moment-by-moment experience on the other. Consider for a moment how many books and movies we’ve all been thoroughly engrossed in for however long it took to read or watch them, only to discover a month or so later that we can’t remember even the broadest strokes of how their plots resolved themselves—much less what their morals might have been.

The answer to the question of what the author is trying to say is that he or she is trying to give readers a sense of what it would be like to go through what the characters are going through—or what it would be like to go through it with them. In other words, authors are not trying to say anything; they’re offering us an experience, once-removed and simulated though it may be. This isn’t to say that these simulated experiences don’t engage our moral emotions; indeed, we’re usually only as engaged in a story as our moral emotions are engaged by it. The problem is that in real-time, in real life, political ideologies, psychoanalytic theories, and rigid ethical principles are too often the farthest thing from helpful. “Fuck the laudable ideologies,” Sabbath helpfully insists: “Shallow, shallow, shallow!” Living in a complicated society with other living, breathing, sick, cruel, saintly, conniving, venal, altruistic, deceitful, noble, horny humans demands not so much a knowledge of the rules as a finely honed body of skills—and our need to develop and hone these skills is precisely why we evolved to find the simulated experiences of fictional narratives both irresistibly fascinating and endlessly pleasurable. Franzen was right that desires are important, the desire to be a good person, the desire to do things others may condemn, the desire to get along with our families and friends and coworkers, the desire to tell them all to fuck off so we can be free, even if just for an hour, to breathe… or to fuck an intern, as the case may be. Grand principles offer little guidance when it comes to balancing these competing desires. This is because, as Sabbath explains, “The law of living: fluctuation. For every thought a counterthought, for every urge a counterurge” (518).

Fiction then is not a conveyance for coded messages—how tedious that would be (how tedious it really is when writers make this mistake); it is rather a simulated experience of moral dilemmas arising from scenarios which pit desire against desire, conviction against reality, desire against conviction, reality against desire, in any and all permutations. Because these experiences are once-removed and, after all, merely fictional, and because they require our sustained attention, the dilemmas tend to play out in the vicinity of life’s extremes. Here’s how Sabbath’s Theater opens:

Either forswear fucking others or the affair is over.

This was the ultimatum, the maddeningly improbable, wholly unforeseen ultimatum, that the mistress of fifty-two delivered in tears to her lover of sixty-four on the anniversary of an attachment that had persisted with an amazing licentiousness—and that, no less amazingly, had stayed their secret—for thirteen years. But now with hormonal infusions ebbing, with the prostate enlarging, with probably no more than another few years of semi-dependable potency still his—with perhaps not that much more life remaining—here at the approach of the end of everything, he was being charged, on pain of losing her, to turn himself inside out. (373)

The ethical proposition that normally applies in situations like this is that adultery is wrong, so don’t commit adultery. But these two have been committing adultery with each other for thirteen years already—do we just stop reading? And if we keep reading, maybe nodding once in a while as we proceed, cracking a few wicked grins along the way, does that mean we too must be guilty?

*****

Much of the fiction written by male literary figures of the past generation, guys like Roth, Mailer, Bellow, and Updike, focuses on the morally charged dilemmas instanced by infidelity, while their gen-x and millennial successors, led by guys like Franzen and David Foster Wallace, have responded to shifting mores—and a greater exposure to academic literary theorizing—by completely overhauling how these dilemmas are framed. Whereas the older generation framed the question as how can we balance the intense physical and spiritual—even existential—gratification of sexual adventure on the one hand with our family obligations on the other, for their successors the question has become how can we males curb our disgusting, immoral, intrinsically oppressive lusting after young women inequitably blessed with time-stamped and overwhelmingly alluring physical attributes. “The younger writers are so self-conscious,” Katie Roiphe writes in a 2009 New York Times essay, “so steeped in a certain kind of liberal education, that their characters can’t condone even their own sexual impulses; they are, in short, too cool for sex.” Roiphe’s essay, “The Naked and the Confused,” stands alongside a 2012 essay in The New York Review of Books by Elaine Blair, “Great American Losers,” as the best descriptions of the new literary trend toward sexually repressed and pathetically timid male leads. The typical character in this vein, Blair writes, “is the opposite of entitled: he approaches women cringingly, bracing for a slap.”

The writers in the new hipster cohort create characters who bury their longings layers-deep in irony because they’ve been assured the failure on the part of men of previous generations to properly check these same impulses played some unspecified role in the abysmal standing of women in society. College students can’t make it past their first semester without hearing about the evils of so-called objectification, but it’s nearly impossible to get a straight answer from anyone, anywhere, to the question of how objectification can be distinguished from normal, non-oppressive male attraction and arousal. Even Roiphe, in her essay lamenting the demise of male sexual virility in literature, relies on a definition of male oppression so broad that it encompasses even the most innocuous space-filling lines in the books of even the most pathetically diffident authors, writing that “the sexism in the work of the heirs apparent” of writers like Roth and Updike,

is simply wilier and shrewder and harder to smoke out. What comes to mind is Franzen’s description of one of his female characters in “The Corrections”: “Denise at 32 was still beautiful.” To the esteemed ladies of the movement I would suggest this is not how our great male novelists would write in the feminist utopia.

How, we may ask, did it get to the point where acknowledging that age influences how attractive a woman is qualifies a man for designation as a sexist? Blair, in her otherwise remarkably trenchant essay, lays the blame for our oversensitivity—though paranoia is probably a better word—at the feet of none other than those great male novelists themselves, or, as David Foster Wallace calls them, the Great Male Narcissists. She writes,

Because of the GMNs, these two tendencies—heroic virility and sexist condescension—have lingered in our minds as somehow yoked together, and the succeeding generations of American male novelists have to some degree accepted the dyad as truth. Behind their skittishness is a fearful suspicion that if a man gets what he wants, sexually speaking, he is probably exploiting someone.

That Roth et al were sexist, condescending, disgusting, narcissistic—these are articles of faith for feminist critics. Yet when we consider how expansive the definition of terms like sexism and misogyny have become—in practical terms, they both translate to: not as radically feminist as me—and the laughably low standard of evidence required to convince scholars of the accusations, female empowerment starts to look like little more than a reserved right to stand in self-righteous judgment of men for giving voice to and acting on desires anyone but the most hardened ideologue will agree are only natural.

The effect on writers of this ever-looming threat of condemnation is that they either allow themselves to be silenced or they opt to participate in the most undignified of spectacles, peevishly sniping their colleagues, falling all over themselves to be granted recognition as champions for the cause. Franzen, at least early in his career, was more the silenced type. Discussing Roth, he wistfully endeavors to give the appearance of having moved beyond his initial moralistic responses. “Eventually,” he says, “I came to feel as if that was coming out of an envy: like, wow, I wish I could be as liberated of worry about other’s people’s opinion of me as Roth is” (55:18). We have to wonder if his espousal of the reductive theory that sympathy for fictional characters is based solely on the strength of their desires derives from this same longing for freedom to express his own. David Foster Wallace, on the other hand, wasn’t quite as enlightened or forgiving when it came to his predecessors. Here’s how he explains his distaste for a character in one of Updike’s novels, openly intimating the author’s complicity:

It’s that he persists in the bizarre adolescent idea that getting to have sex with whomever one wants whenever one wants is a cure for ontological despair. And so, it appears, does Mr. Updike—he makes it plain that he views the narrator’s impotence as catastrophic, as the ultimate symbol of death itself, and he clearly wants us to mourn it as much as Turnbull does. I’m not especially offended by this attitude; I mostly just don’t get it. Erect or flaccid, Ben Turnbull’s unhappiness is obvious right from the book’s first page. But it never once occurs to him that the reason he’s so unhappy is that he’s an asshole.

So the character is an asshole because he wants to have sex outside of marriage, and he’s unhappy because he’s an asshole, and it all traces back to the idea that having sex with whomever one wants is a source of happiness? Sounds like quite the dilemma—and one that pronouncing the main player an asshole does nothing to solve. This passage is the conclusion to a review in which Wallace tries to square his admiration for Updike’s writing with his desire to please a cohort of women readers infuriated by the way Updike writes about—portrays—women (which begs the question of why they’d read so many of his books). The troubling implication of his compromise is that if Wallace were himself to freely express his sexual feelings, he’d be open to the charge of sexism too—he’d be an asshole. Better to insist he simply doesn’t “get” why indulging his sexual desires might alleviate his “ontological despair.” What would Mickey Sabbath make of the fact that Wallace hanged himself when he was only forty-six, eleven years after publishing that review? (This isn’t just a nasty rhetorical point; Sabbath has a fascination with artists who commit suicide.)

The inadequacy of moral codes and dehumanizing ideologies when it comes to guiding real humans through life’s dilemmas, along with their corrosive effects on art, is the abiding theme of Sabbath’s Theater. One of the pivotal moments in Sabbath’s life is when a twenty-year-old student he’s in the process of seducing leaves a tape recorder out to be discovered in a lady’s room at the university. The student, Kathy Goolsbee, has recorded a phone sex session between her and Sabbath, and when the tape finds its way into the hands of the dean, it becomes grounds for the formation of a committee of activists against the abuse of women. At first, Kathy doesn’t realize how bad things are about to get for Sabbath. She even offers to give him a blow job as he berates her for her carelessness. Trying to impress on her the situation’s seriousness, he says,

Your people have on tape my voice giving reality to all the worst things they want the world to know about men. They have a hundred times more proof of my criminality than could be required by even the most lenient of deans to drive me out of every decent antiphallic educational institution in America. (586)

The committee against Sabbath proceeds to make the full recorded conversation available through a call-in line (the nineties equivalent of posting the podcast online). But the conversation itself isn’t enough; one of the activists gives a long introduction, which concludes,

The listener will quickly recognize how by this point in his psychological assault on an inexperienced young woman, Professor Sabbath has been able to manipulate her into thinking that she is a willing participant. (567-8)

Sabbath knows full well that even consensual phone sex can be construed as a crime if doing so furthers the agenda of those “esteemed ladies of the movement” Roiphe addresses.

Reading through the lens of a tribal ideology ineluctably leads to the refraction of reality beyond recognizability, and any aspiring male writer quickly learns in all his courses in literary theory that the criteria for designation as an enemy to the cause of women are pretty much whatever the feminist critics fucking say they are. Wallace wasn’t alone in acquiescing to feminist rage by denying his own boorish instincts. Roiphe describes the havoc this opportunistic antipathy toward male sexuality wreaks in the minds of male writers and their literary creations:

Rather than an interest in conquest or consummation, there is an obsessive fascination with trepidation, and with a convoluted, postfeminist second-guessing. Compare [Benjamin] Kunkel’s tentative and guilt-ridden masturbation scene in “Indecision” with Roth’s famous onanistic exuberance with apple cores, liver and candy wrappers in “Portnoy’s Complaint.” Kunkel: “Feeling extremely uncouth, I put my penis away. I might have thrown it away if I could.” Roth also writes about guilt, of course, but a guilt overridden and swept away, joyously subsumed in the sheer energy of taboo smashing: “How insane whipping out my joint like that! Imagine what would have been had I been caught red-handed! Imagine if I had gone ahead.” In other words, one rarely gets the sense in Roth that he would throw away his penis if he could.

And what good comes of an ideology that encourages the psychological torture of bookish young men? It’s hard to distinguish the effects of these so-called literary theories from the hellfire scoldings delivered from the pulpits of the most draconian and anti-humanist religious patriarchs. Do we really need to ideologically castrate all our male scholars to protect women from abuse and further the cause of equality?

*****

The experience of sexual relations between older teacher and younger student in Sabbath’s Theater is described much differently when the gender activists have yet to get involved—and not just by Sabbath but by Kathy as well. “I’m of age!” she protests as he chastises her for endangering his job and opening him up to public scorn; “I do what I want” (586). Absent the committee against him, Sabbath’s impression of how his affairs with his students impact them reflects the nuance of feeling inspired by these experimental entanglements, the kind of nuance that the “laudable ideologies” can’t even begin to capture.

There was a kind of art in his providing an illicit adventure not with a boy of their own age but with someone three times their age—the very repugnance that his aging body inspired in them had to make their adventure with him feel a little like a crime and thereby give free play to their budding perversity and to the confused exhilaration that comes of flirting with disgrace. Yes, despite everything, he had the artistry still to open up to them the lurid interstices of life, often for the first time since they’d given their debut “b.j.” in junior high. As Kathy told him in that language which they all used and which made him want to cut their heads off, through coming to know him she felt “empowered.” (566)

Opening up “the lurid interstices of life” is precisely what Roth and the other great male writers—all great writers—are about. If there are easy answers to the questions of what characters should do, or if the plot entails no more than a simple conflict between a blandly good character and a blandly bad one, then the story, however virtuous its message, will go unattended.

But might there be too much at stake for us impressionable readers to be allowed free reign to play around in imaginary spheres peopled by morally dubious specters? After all, if denouncing the dreamworlds of privileged white men, however unfairly, redounds to the benefit of women and children and minorities, then perhaps it’s to the greater good. In fact, though, right alongside the trends of increasing availability for increasingly graphic media portrayals of sex and violence have occurred marked decreases in actual violence and the abuse of women. And does anyone really believe it’s the least literate, least media-saturated societies that are the kindest to women? The simple fact is that the theory of literature subtly encouraging oppression can’t be valid. But the problem is once ideologies are institutionalized, once a threshold number of people depend on their perpetuation for their livelihoods, people whose scholarly work and reputations are staked on them, then victims of oppression will be found, their existence insisted on, regardless of whether they truly exist or not.

In another scandal Sabbath was embroiled in long before his flirtation with Kathy Goolsbee, he was brought up on charges of indecency because in the course of a street performance he’d exposed a woman’s nipple. The woman herself, Helen Trumbull, maintains from the outset of the imbroglio that whatever Sabbath had done, he’d done it with her consent—just as will be the case with his “psychological assault” on Kathy. But even as Sabbath sits assured that the case against him will collapse once the jury hears the supposed victim testify on his behalf, the prosecution takes a bizarre twist:

In fact, the victim, if there even is one, is coming this way, but the prosecutor says no, the victim is the public. The poor public, getting the shaft from this fucking drifter, this artist. If this guy can walk along a street, he says, and do this, then little kids think it’s permissible to do this, and if little kids think it’s permissible to do this, then they think it’s permissible to blah blah banks, rape women, use knives. If seven-year-old kids—the seven nonexistent kids are now seven seven-year-old kids—are going to see that this is fun and permissible with strange women… (663-4)

Here we have Roth’s dramatization of the fundamental conflict between artists and moralists. Even if no one is directly hurt by playful scenarios, that they carry a message, one that threatens to corrupt susceptible minds, is so seemingly obvious it’s all but impossible to refute. Since the audience for art is “the public,” the acts of depravity and degradation it depicts are, if anything, even more fraught with moral and political peril than any offense against an individual victim, real or imagined.

This theme of the oppressive nature of ideologies devised to combat oppression, the victimizing proclivity of movements originally fomented to protect and empower victims, is most directly articulated by a young man named Donald, dressed in all black and sitting atop a file cabinet in a nurse’s station when Sabbath happens across him at a rehab clinic. Donald “vaguely resembled the Sabbath of some thirty years ago,” and Sabbath will go on to apologize for interrupting him, referring to him as “a man whose aversions I wholeheartedly endorse.” What he was saying before the interruption:

“Ideological idiots!” proclaimed the young man in black. “The third great ideological failure of the twentieth century. The same stuff. Fascism. Communism. Feminism. All designed to turn one group of people against another group of people. The good Aryans against the bad others who oppress them. The good poor against the bad rich who oppress them. The good women against the bad men who oppress them. The holder of ideology is pure and good and clean and the other wicked. But do you know who is wicked? Whoever imagines himself to be pure is wicked! I am pure, you are wicked… There is no human purity! It does not exist! It cannot exist!” he said, kicking the file cabinet for emphasis. “It must not and should not exist! Because it’s a lie. … Ideological tyranny. It’s the disease of the century. The ideology institutionalizes the pathology. In twenty years there will be a new ideology. People against dogs. The dogs are to blame for our lives as people. Then after dogs there will be what? Who will be to blame for corrupting our purity?” (620-1)

It’s noteworthy that this rant is made by a character other than Sabbath. By this point in the novel, we know Sabbath wouldn’t speak so artlessly—unless he was really frightened or angry. As effective and entertaining an indictment of “Ideological tyranny” as Sabbath’s Theater is, we shouldn’t expect to encounter anywhere in a novel by a storyteller as masterful as Roth a character operating as a mere mouthpiece for some argument. Even Donald himself, Sabbath quickly gleans, isn’t simply spouting off; he’s trying to impress one of the nurses.

And it’s not just the political ideologies that conscript complicated human beings into simple roles as oppressors and victims. The pseudoscientific psychological theories that both inform literary scholarship and guide many non-scholars through life crises and relationship difficulties function according to the same fundamental dynamic of tribalism; they simply substitute abusive family members for more generalized societal oppression and distorted or fabricated crimes committed in the victim’s childhood for broader social injustices. Sabbath is forced to contend with this particular brand of depersonalizing ideology because his second wife, Roseanna, picks it up through her AA meetings, and then becomes further enmeshed in it through individual treatment with a therapist named Barbara. Sabbath, who considers himself a failure, and who is carrying on an affair with the woman we meet in the opening lines of the novel, is baffled as to why Roseanna would stay with him. Her therapist provides an answer of sorts.

But then her problem with Sabbath, the “enslavement,” stemmed, according to Barbara, from her disastrous history with an emotionally irresponsible mother and a violent alcoholic father for both of whom Sabbath was the sadistic doppelganger. (454)

Roseanna’s father was a geology professor who hanged himself when she was a young teenager. Sabbath is a former puppeteer with crippling arthritis. Naturally, he’s confused by the purported identity of roles.

These connections—between the mother, the father, and him—were far clearer to Barbara than they were to Sabbath; if there was, as she liked to put it, a “pattern” in it all, the pattern eluded him. In the midst of a shouting match, Sabbath tells his wife, “As for the ‘pattern’ governing a life, tell Barbara it’s commonly called chaos” (455).

When she protests, “You are shouting at me like my father,” Sabbath asserts his individuality: “The fuck that’s who I’m shouting at you like! I’m shouting at you like myself!” (459). Whether you see his resistance as heroic or not probably depends on how much credence you give to those psychological theories.

From the opening lines of Sabbath’s Theater when we’re presented with the dilemma of the teary-eyed mistress demanding monogamy in their adulterous relationship, the simple response would be to stand in easy judgment of Sabbath, and like Wallace did to Updike’s character, declare him an asshole. It’s clear that he loves this woman, a Croatian immigrant named Drenka, a character who at points steals the show even from the larger-than-life protagonist. And it’s clear his fidelity would mean a lot to her. Is his freedom to fuck other women really so important? Isn’t he just being selfish? But only a few pages later our easy judgment suddenly gets more complicated:

As it happened, since picking up Christa several years back Sabbath had not really been the adventurous libertine Drenka claimed she could no longer endure, and consequently she already had the monogamous man she wanted, even if she didn’t know it. To women other than her, Sabbath was by now quite unalluring, not just because he was absurdly bearded and obstinately peculiar and overweight and aging in every obvious way but because, in the aftermath of the scandal four years earlier with Kathy Goolsbee, he’s become more dedicated than ever to marshaling the antipathy of just about everyone as though he were, in fact, battling for his rights. (394)

Christa was a young woman who participated in a threesome with Sabbath and Drenka, an encounter to which Sabbath’s only tangible contribution was to hand the younger woman a dildo.

One of the central dilemmas for a character who loves the thrill of sex, who seeks in it a rekindling of youthful vigor—“the word’s rejuvenation,” Sabbath muses at one point (517)—the adrenaline boost borne of being in the wrong and the threat of getting caught, what Roiphe calls “the sheer energy of taboo smashing,” becomes ever more indispensable as libido wanes with age. Even before Sabbath ever had to contend with the ravages of aging, he reveled in this added exhilaration that attends any expedition into forbidden realms. What makes Drenka so perfect for him is that she has not just a similarly voracious appetite but a similar fondness for outrageous sex and the smashing of taboo. And it’s this mutual celebration of the verboten that Sabbath is so reluctant to relinquish. Of Drenka, he thinks,

The secret realm of thrills and concealment, this was the poetry of her existence. Her crudeness was the most distinguishing force in her life, lent her life its distinction. What was she otherwise? What was he otherwise? She was his last link with another world, she and her great taste for the impermissible. As a teacher of estrangement from the ordinary, he had never trained a more gifted pupil; instead of being joined by the contractual they were interconnected by the instinctual and together could eroticize anything (except their spouses). Each of their marriages cried out for a countermarriage in which the adulterers attack their feelings of captivity. (395)

Those feelings of captivity, the yearnings to experience the flow of the old juices, are anything but adolescent, as Wallace suggests of them; adolescents have a few decades before they have to worry about dwindling arousal. Most of them have the opposite problem.

The question of how readers are supposed to feel about a character like Sabbath doesn’t have any simple answers. He’s an asshole at several points in the novel, but at several points he’s not. One of the reasons he’s so compelling is that working out what our response to him should be poses a moral dilemma of its own. Whether or not we ultimately decide that adultery is always and everywhere wrong, the experience of being privy to Sabbath’s perspective can help us prepare ourselves for our own feelings of captivity, lusting nostalgia, and sexual temptation. Most of us will never find ourselves in a dilemma like Sabbath gets himself tangled in with his friend Norman’s wife, for instance, but it would be to our detriment to automatically discount the old hornball’s insights.

He could discern in her, whenever her husband spoke, the desire to be just a little cruel to Norman, saw her sneering at the best of him, at the very best things in him. If you don’t go crazy because of your husband’s vices, you go crazy because of his virtues. He’s on Prozac because he can’t win. Everything is leaving her except for her behind, which her wardrobe informs her is broadening by the season—and except for this steadfast prince of a man marked by reasonableness and ethical obligation the way others are marked by insanity or illness. Sabbath understood her state of mind, her state of life, her state of suffering: dusk is descending, and sex, our greatest luxury, is racing away at a tremendous speed, everything is racing off at a tremendous speed and you wonder at your folly in having ever turned down a single squalid fuck. You’d give your right arm for one if you are a babe like this. It’s not unlike the Great Depression, not unlike going broke overnight after years of raking it in. “Nothing unforeseen that happens,” the hot flashes inform her, “is likely ever again going to be good.” Hot flashes mockingly mimicking the sexual ecstasies. Dipped, she is, in the very fire of fleeting time. (651)

Welcome to messy, chaotic, complicated life.

Sabbath’s Theater is, in part, Philip Roth’s raised middle finger to the academic moralists whose idiotic and dehumanizing ideologies have spread like a cancer into all the venues where literature is discussed and all the avenues through which it’s produced. Unfortunately, the unrecognized need for culture-wide chemotherapy hasn’t gotten any less dire in the nearly two decades since the novel was published. With literature now drowning in the devouring tide of new media, the tragic course set by the academic custodians of art toward bloodless prudery and impotent sterility in the name of misguided political activism promises to do nothing but ensure the ever greater obsolescence of epistemologically doomed and resoundingly pointless theorizing, making of college courses the places where you go to become, at best, profoundly confused about where you should stand with relation to fiction and fictional characters, and, at worst, a self-righteous demagogue denouncing the chimerical evils allegedly encoded into every text or cultural artifact. All the conspiracy theorizing about the latent evil urgings of literature has amounted to little more than another reason not to read, another reason to tune in to Breaking Bad or Mad Men instead. But the only reason Roth’s novel makes such a successful case is that it at no point allows itself to be reducible to a mere case, just as Sabbath at no point allows himself to be conscripted as a mere argument. We don’t love or hate him; we love and hate him. But we sort of just love him because he leaves us free to do both as we experience his antics, once removed and simulated, but still just as complicatedly eloquent in their message of “Fuck the laudable ideologies”—or not, as the case may be.

Also read

JUST ANOTHER PIECE OF SLEAZE: THE REAL LESSON OF ROBERT BOROFSKY'S "FIERCE CONTROVERSY"

And

PUTTING DOWN THE PEN: HOW SCHOOL TEACHES US THE WORST POSSIBLE WAY TO READ LITERATURE

And

Freud: The Falsified Cipher

Upon entering a graduate program in literature, I was appalled to find that Freud’s influence was alive and well in the department. Didn’t they know that nearly all of Freud’s theories have been disproven? Didn’t they know psychoanalysis is pseudoscience?

[As I'm hard at work on a story, I thought I'd post an essay from my first course as a graduate student on literary criticism. It was in the fall of 2009, and I was shocked and appalled that not only were Freud's ideas still being taught but there was no awareness whatsoever that psychology had moved beyond them. This is my attempt at righting the record while keeping my tone in check.]

The matter of epistemology in literary criticism is closely tied to the question of what end the discipline is supposed to serve. How critics decide what standard of truth to adhere to is determined by the role they see their work playing, both in academia and beyond. Freud stands apart as a literary theorist, professing in his works a commitment to scientific rigor in a field that generally holds belief in even the possibility of objectivity as at best naïve and at worst bourgeois or fascist. For the postmodernists, both science and literature are suspiciously shot through with the ideological underpinnings of capitalist European male hegemony, which they take as their duty to undermine. Their standard of truth, therefore, seems to be whether a theory or application effectively exposes one or another element of that ideology to “interrogation.” Admirable as the values underlying this patently political reading of texts are, the science-minded critic might worry lest such an approach merely lead straight back to the a priori assumptions from which it set forth. Now, a century after Freud revealed the theory and practice of psychoanalysis, his attempt to interpret literature scientifically seems like one possible route of escape from the circularity (and obscurantism) of postmodernism. Unfortunately, Freud’s theories have suffered multiple devastating empirical failures, and Freud himself has been shown to be less a committed scientist than an ingenious fabulist, but it may be possible to salvage from the failures of psychoanalysis some key to a viable epistemology of criticism.

A text dating from early in the development of psychoanalysis shows both the nature of Freud’s methods and some of the most important substance of his supposed discoveries. Describing his theory of the Oedipus complex in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud refers vaguely to “observations on normal children,” to which he compares his experiences with “psychoneurotics” to arrive at his idea that both display, to varying degrees, “feelings of love and hatred to their parents” (920). There is little to object to in this rather mundane observation, but Freud feels compelled to write that his discovery is confirmed by a legend,

…a legend whose profound and universal power to move can only be understood if the hypothesis I have put forward in regard to the psychology of children has an equally universal validity. (920)

He proceeds to relate the Sophocles drama from which his theory gets its name. In the story, Oedipus is tricked by fate into killing his father and marrying his mother. Freud takes this as evidence that the love and hatred he has observed in children are of a particular kind. According to his theory, any male child is fated to “direct his first sexual impulse towards his mother” and his “first murderous wish against his father” (921). But Freud originally poses this idea as purely hypothetical. What settles the issue is evidence he gleans from dream interpretations. “Our dreams,” he writes, “convince us that this is so” (921). Many men, it seems, confided to him that they dreamt of having sex with their mothers and killing their fathers.

Freud’s method, then, was to seek a thematic confluence between men’s dreams, the stories they find moving, and the behaviors they display as children, which he knew mostly through self-reporting years after the fact. Indeed, the entire edifice of psychoanalysis is purported to have been erected on this epistemic foundation. In a later essay on “The Uncanny,” Freud makes the sources of his ideas even more explicit. “We know from psychoanalytic experience,” he writes, “that the fear of damaging or losing one’s eyes is a terrible one in children” (35). A few lines down, he claims that, “A study of dreams, phantasies and myths has taught us that anxiety about one’s eyes…is a substitute for the dread of being castrated” (36). Here he’s referring to another facet of the Oedipus complex which theorizes that the child keeps his sexual desire for his mother in check because of the threat of castration posed by his jealous father. It is through this fear of his father, which transforms into grudging respect, and then into emulation, that the boy learns his role as a male in society. And it is through the act of repressing his sexual desire for his mother that he first develops his unconscious, which will grow into a general repository of unwanted desires and memories (Eagleton 134).

But what led Freud to this theory of repression, which suggests that we have the ability to willfully forget troubling incidents and drive urges to some portion of our minds to which we have no conscious access? He must have arrived at an understanding of this process in the same stroke that led to his conclusions about the Oedipus complex, because, in order to put forth the idea that as children we all hated one parent and wanted to have sex with the other, he had to contend with the fact that most people find the idea repulsive. What accounts for the dramatic shift between childhood desires and those of adults? What accounts for our failure to remember the earlier stage? The concept of repression had to be firmly established before Freud could make such claims. Of course, he could have simply imported the idea from another scientific field, but there is no evidence he did so. So it seems that he relied on the same methods—psychoanalysis, dream interpretation, and the study of myths and legends—to arrive at his theories as he did to test them. Inspiration and confirmation were one and the same.

Notwithstanding Freud’s claim that the emotional power of the Oedipus legend “can only be understood” if his hypothesis about young boys wanting to have sex with their mothers and kill their fathers has “universal validity,” there is at least one alternative hypothesis which has the advantage of not being bizarre. It could be that the point of Sophocles’s drama was that fate is so powerful it can bring about exactly the eventualities we most desire to avoid. What moves audiences and readers is not any sense of recognition of repressed desires, but rather compassion for the man who despite, even because of, his heroic efforts fell into this most horrible of traps. (Should we assume that the enduring popularity of W.W. Jacobs’s story, “The Monkey’s Paw,” which tells a similar fated story about a couple who inadvertently wish their son dead, proves that all parents want to kill their children?) The story could be moving because it deals with events we would never want to happen. It is true however that this hypothesis fails to account for why people enjoy watching such a tragedy being enacted—but then so does Freud’s. If we have spent our conscious lives burying the memory of our childhood desires because they are so unpleasant to contemplate, it makes little sense that we should find pleasure in seeing those desires acted out on stage. And assuming this alternative hypothesis is at least as plausible as Freud’s, we are left with no evidence whatsoever to support his theory of repressed childhood desires.

To be fair, Freud did look beyond the dreams and myths of men of European descent to test the applicability of his theories. In his book Totem and Taboo he inventories “savage” cultures and adduces the universality among them of a taboo against incest as further proof of the Oedipus complex. He even goes so far as to cite a rival theory put forth by a contemporary:

Westermarck has explained the horror of incest on the ground that “there is an innate aversion to sexual intercourse between persons living very closely together from early youth, and that, as such persons are in most cases related by blood, this feeling would naturally display itself in custom and law as a horror of intercourse between near kin.” (152)

To dismiss Westermarck’s theory, Freud cites J. G. Frazer, who argues that laws exist only to prevent us from doing things we would otherwise do or prod us into doing what we otherwise would not. That there is a taboo against incest must therefore signal that there is no innate aversion, but rather a proclivity, for incest. Here it must be noted that the incest Freud had in mind includes not just lust for the mother but for sisters as well. “Psychoanalysis has taught us,” he writes, again vaguely referencing his clinical method, “that a boy’s earliest choice of objects for his love is incestuous and that those objects are forbidden ones—his mother and sister” (22). Frazer’s argument is compelling, but Freud’s test of the applicability of his theories is not the same as a test of their validity (though it seems customary in literary criticism to conflate the two).

As linguist and cognitive neuroscientist Steven Pinker explains in How the Mind Works, in tests of validity Westermarck beats Freud hands down. Citing the research of Arthur Wolf, he explains that without setting out to do so, several cultures have conducted experiments on the nature of incest aversion. Israeli kibbutzim, in which children grew up in close proximity to several unrelated agemates, and the Chinese and Taiwanese practice of adopting future brides for sons and raising them together as siblings are just two that Wolf examined. When children from the kibbutzim reached sexual maturity, even though there was no discouragement from adults for them to date or marry, they showed a marked distaste for each other as romantic partners. And compared to more traditional marriages, those in which the bride and groom grew up in conditions mimicking siblinghood were overwhelmingly “unhappy, unfaithful, unfecund, and short” (459). The effect of proximity in early childhood seems to apply to parents as well, at least when it comes to fathers’ sexual feelings for their daughters. Pinker cites research that shows the fathers who sexually abuse their daughters tend to be the ones who have spent the least time with them as infants, while the stepdads who actually do spend a lot of time with their stepdaughters are no more likely to abuse them than their biological parents. These studies not only favor Westermarck’s theory; they also provide a counter to Frazer’s objection to it. Human societies are so complex that we often grow up in close proximity with people who are unrelated, or don’t grow up with people who are, and therefore it is necessary for there to be a cultural proscription—a taboo—against incest in addition to the natural mechanism of aversion.

Among biologists and anthropologists, what is now called the Westermarck effect has displaced Freud’s Oedipus complex as the best explanation for incest avoidance. Since Freud’s theory of childhood sexual desires has been shown to be false, the question arises of where this leaves his concept of repression. According to literary critic—and critic of literary criticism—Frederick Crews, repression came to serve in the 1980’s and 90’s a role equivalent to the “spectral evidence” used in the Salem witch trials. Several psychotherapists latched on to the idea that children can store reliable information in their memories, especially when that information is too terrible for them to consciously handle. And the testimony of these therapists has led to many convictions and prison sentences. But the evidence for this notion of repression is solely clinical—modern therapists base their conclusions on interactions with patients, just as Freud did. Unfortunately, researchers outside the clinical setting are unable to find any phenomenon answering to the description of repressed but retrievable memories. Crews points out that there are plenty of people who are known to have survived traumatic experiences: “Holocaust survivors make up the most famous class of such subjects, but whatever group or trauma is chosen, the upshot of well-conducted research is always the same” (158). That upshot: