Essays and Book Reviews on Evolutionary Psychology, Anthropology, the Literature of Science and the Science of Literature

"The Dawn of Everything" and the Demarcation between Science and Propaganda

As Graeber and Wengrow glibly generalize about the state of scholarship in their fields, only to turn around and poke holes in their semi-fictional accounts, you start to feel like you’ve been buttonholed by an old man at a bar as he tells a series of tendentious stories about how he bested impossibly dense adversaries in battles of wit. Indeed, the overarching problem with The Dawn of Everything is that it consists primarily of a long rant against the straw man of lockstep societal progression through rigid stages.

The Dawn of Everything and the Demarcation between Science and Propaganda

[A sleeker and much shorter version of this article was published in Quillette under the title “The Dawn of Everything” and the Politics of Human Prehistory. This version retains some of my wordier stylistic flourishes, more of my personal take, and longer discussions about Heard’s thesis and the connection between societal scale and political concentration.]

In 1885, Thomas Henry Huxley delivered a speech in which he famously declared that science “commits suicide the moment it adopts a creed.” The occasion was the completion of a statue of Charles Darwin for the British Museum, yet the man known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” felt obliged to emphasize that the monument should in no way be taken as an official sanction of Darwin’s ideas, because “science does not recognize such sanctions.” In science, the status of any idea is contingent upon the strength of the evidence supporting it and must therefore be treated as provisional as data accumulates and our understanding deepens. Huxley intended his aphorism as a reminder that no belief, whether personal, political, religious, or even scientific, should be immune to questioning and revision.

While many scientists continue to uphold the strict separation between scientific research and political advocacy, a growing number now argue that the convention of barring creeds from science is quaint—even reactionary. This trend is especially pronounced in the social sciences. As Allison Mickel and Kyle Olson write in a 2021 op-ed for Sapiens titled “Archaeologists Should Be Activists Too,”

There are still some who argue that scientists maintain their authority only when they remain objective, separate from current political concerns. Many academics have decried this view for decades, demonstrating that fully objective science has always been more of a myth than a reality. Science has always been shaped by the contemporary concerns of the time and place in which research occurs.

The suggestion here is that since researchers can never thoroughly eliminate politics from their work, they may as well ensure they are incorporating the correct politics into their foundational assumptions. We might call this the argument from inevitability. The “correct” politics are taken by most activists to consist of whatever is most beneficial to marginalized peoples—which usually means uncritically accepting their own views or, if those views are inaccessible, choosing whatever narrative paints them in the most favorable light. Let’s call this the default to the presumed victim’s truth.

While this reasoning strikes many as both convincing and morally commendable, its flaws are easy to detect. For instance, the inevitability of political concerns coloring our research offers no justification for abandoning efforts at reducing their impact. Pathogenic microbes will inevitably survive any effort at sanitizing an operating theater. That hardly means surgeons should perform procedures in gas station bathrooms. Those whose goal is to arrive at the clearest and most comprehensive understanding of reality must strive to minimize the influence of prejudices arising from nonscientific beliefs and agendas as much as humanly possible—even if eradicating them completely is beyond anyone’s capability. And, while it may seem admirable, even heroic, to err on the side of protecting those who may not be able to protect themselves, defaulting to the presumed victim’s truth comes with two obvious drawbacks. First, over time the defaulters’ credibility will suffer, as they have clearly chosen a side. And second, the presumed victim’s truth may simply not be true at all, or it may overshadow elements of the truth that could lead to a deeper, more thorough understanding. (A third and less obvious drawback is that privileging the victim’s perspective has the side-effect of pitting groups with competing claims of victimhood against each other for the status of truer, or bigger, victim.)

The late anthropologist and anarchist David Graeber presents a case study in what happens when you allow creeds and political interests to creep into your attempts at reasoning scientifically. For decades, Graeber participated in leftist and radical movements, and he was one of the original planners—an “anti-leader”—for the Occupy Wall Street protest. In January of 2017, he tweeted a question: “does anyone know any handy rebuttals to the neoliberal/conservative numbers on social progress over the last 30 years?” In the thread that followed, Graeber elaborated:

again & again i see these guys trundling out #s that absolute poverty, illiteracy, child malnutrition, child labor, have sharply declined...that life expectancy & education levels have gone way up, worldwide, thus showing the age of structural adjustment etc was a good thing. It strikes me as highly unlikely these numbers are right … It’s clear this is all put together by right-wing think tanks. Yet where’s the other sides numbers? I’ve found no clear rebuttals.

Graeber responded to charges of motivated reasoning in the comments by insisting he was merely demonstrating a scientist’s proper skepticism by looking for counterevidence. What he failed to understand was that it wasn’t the question itself that revealed his bias. It was that he characterized the data he was inquiring into as “neoliberal/conservative,” assuming without evidence they were “put together by right-wing think tanks.” Rather than treating the data as a possible window onto the nature of our civilization, he saw the numbers as points on a scoreboard for the opposing team, which he assumed could only have been counted because of partisan refereeing.

Graeber died in 2020, but he continues his challenge to the narrative of social progress in his posthumously published book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, which he cowrote with the archeologist David Wengrow. Their main thesis is that it is long past time to scrap the traditional story of how human societies evolve from egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers to larger, more sedentary tribes to more hierarchical chiefdoms to highly stratified states governed by authoritarian rulers. This narrative, they argue, can be traced back to either Jean-Jacques Rousseau (if you believe that hunter-gatherers were peaceful and freedom-loving) or to Thomas Hobbes (if you believe they were miserable and warlike).

“Our objections can be classified into three broad categories,” they write in the first chapter, but only one of these objections is scientific: “these two alternatives,” the authors claim, “simply aren’t true.” The next two bullets complain that the conventional stories “have dire political implications,” and “make the past needlessly dull” (3). Graeber and Wengrow are troubled that ascendent social evolutionary theories treat hunter-gatherers as either savages or “innocent children of nature” (441), instead of crediting them with formulating lofty ideas about freedom and recognizing their ability to experiment with various social arrangements.

Unfortunately, the supposedly conventional thinking Graeber and Wengrow outline at the beginning of each of their book’s sections usually comes with few if any citations, and when they do reference their colleagues’ work, they frequently misrepresent it. Over time, as they glibly generalize about the state of scholarship in their fields, only to turn around and poke holes in their semi-fictional accounts, you start to feel like you’ve been buttonholed by an old man at a bar as he tells a series of tendentious stories about how he bested impossibly dense adversaries in battles of wit. Indeed, the overarching problem with The Dawn of Everything is that it consists primarily of a long rant against the straw man of lockstep societal progression through rigid stages—even though it becomes clear Graeber and Wengrow’s true beef is with scholars who argue that large societies require some form of government domination, an issue suspiciously close to the heart of any good anarchist.

Graeber and Wengrow paint a picture of the study of human prehistory as dominated by researchers who take it as a matter of faith that societies everywhere will inevitably progress through identical stages, driven by the same key technological developments, to arrive at one form or another of a modern state, which is characterized by heavy-handed, top-down control of the masses by the wealthy and powerful few. Late in the book, they admit that “almost nobody today subscribes to this framework in its entirety,” and go on to suggest the real problem is that

if our fields have moved on, they have done so, it seems, without putting an alternative vision in place, the result being that almost anyone who is not an archaeologist or anthropologist tends to fall back on the older scheme when they set out to think or write about world history on a large canvas. (447)

But to create the illusion that they are taking on the prevailing view, which they insist is disproportionately influenced by non-specialists, Graeber and Wengrow are forced to conflate modern scholarship with ideas from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. This is because modern scholars—both in and out of the field of anthropology—know better than to posit hard-and-fast rules about human behavior and society. Instead, they look for trends and correlations, as in the observation that hunter-gatherers tend to live in small-scale societies that tend to be egalitarian.

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm, for instance, has penned some of the most widely cited books on hunter-gatherer egalitarianism. In the introduction to his book Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, he writes, “I make the major assumption that humans were egalitarian for thousands of generations before hierarchical societies began to appear.” Graeber and Wengrow fault him for claiming “we were strictly ‘egalitarian for thousands of generations’,” though Boehm never used the word “strictly,” and it becomes clear his theory allows for exceptions. Graeber and Wengrow go on, “So, according to Boehm, for about 200,000 years political animals all chose to live the same way.” They complain of his, “odd insistence that for many tens of thousands of years, nothing happened” (87). But Boehm insists on nothing of the sort. He writes,

When upstarts try to make inroads against an egalitarian social order, they will be quickly recognized and, in many cases, quickly curbed on a preemptive basis. One reason for this sensitivity is that the oral tradition of a band (which included knowledge from adjacent bands) will preserve stories about serious domination episodes. (87)

If there were “domination episodes,” then something happened. If that isn’t clear enough, Boehm later writes that “a hunting and gathering way of life in itself does not guarantee a decisively egalitarian political orientation” (89).

Does Boehm really claim humans in the Pleistocene all lived the same way? In fact, he explicitly argues the opposite: “We must keep in mind that in Paleolithic times the planet’s best environments were available to foragers whose social and adaptive patterns varied across a very wide spectrum” (211). Graeber and Wengrow’s misrepresentation is especially frustrating because the implications of recent discoveries of hunter-gatherer earthworks and monumental building for theories like Boehm’s are important, but the authors apparently can’t help flattening his ideas and robbing them of nuance. Their goal appears to be nothing other than to bolster the impression that anyone whose perspective diverges from theirs must suffer from a stunted imagination. “Blinded by the ‘just so’ story of how human societies evolved,” they write of their colleagues, “they can’t even see half of what’s now before their eyes” (442).

The two scholars whose work—and reputations—suffer the most scathing attacks in The Dawn of Everything, Jared Diamond and Steven Pinker, also rely on the traditional sequence of cultural evolutionism in their works, but they both use Elman Service’s terms “band,” “tribe,” “chiefdom,” and “state” as descriptive categories, not as an explanatory theory of clockwork progression. Graeber and Wengrow nonetheless claim Diamond’s theory is that what spelled doom for hunter-gatherer egalitarianism was farming. “For Diamond,” they write,

as for Rousseau some centuries earlier, what put an end to that equality—everywhere and forever—was the invention of agriculture, and the higher population levels it sustained. Agriculture brought about a transition from “bands” to “tribes.” Accumulation of food surplus fed population growth, leading some “tribes” to develop into ranked societies known as “chiefdoms.” (10)

Did Diamond really argue that agriculture causes a series of transitions to more complex societies “everywhere and forever”? In the section of his book The World until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? Graeber and Wengrow cite, Diamond writes,

The higher populations of tribes than of bands require more food to support more people in a small area, and so tribes usually are farmers or herders or both, but a few are hunter-gatherers living in especially productive environments (such as Japan’s Ainu people and North America’s Pacific Northwest Indians). (15)

So, rather than asserting that agriculture sets off an inevitable march toward despotism, Diamond writes of trends and correlations, leaving unanswered the question of which direction the causal arrow points. He makes this focus on trends explicit very near some of the text that Graeber and Wengrow quote.

While every human society is unique, there are also cross-cultural patterns that permit some generalizations. In particular, there are correlated trends in at least four aspects of societies: population size, subsistence, political centralization, and social stratification. (12-3)

Diamond’s emphasis on correlations, and on the importance of keeping exceptions in mind, is part of a page-and-a-half discussion of the advantages and drawbacks of using the traditional classification scheme.

Of course, disproving a categorical statement is far easier than refuting an argument about relative frequencies, so it’s easy to understand the temptation. All Graeber and Wengrow need to torch their straw man version of Diamond’s ideas is to provide a counterexample or two, and that is precisely what they attempt to do in the following chapters. To get the real story of what factors contribute to the increasing scale and complexity of a society, you would need to go beyond searching for examples or counterexamples for a given narrative. You would have to do some math and statistics. (It so happens researchers have conducted just this type of statistical analysis into the factors driving increasing scale and complexity, though the findings were published after The Dawn of Everything. The results show that agriculture is indeed one of the two most important factors—the other being warfare.)

The “dire political implications” of believing agriculture leads to complexity and domination have a clear impact on the conclusions reached by Graeber and Wengrow, and the line separating their science from their politics only gets blurrier from here. Summarizing their case that the old evolutionary theories “simply aren’t true,” they write,

To give just a sense of how different the emerging picture is: it is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory. Agriculture, in turn, did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies. And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers, ambitious warrior-politicians, or even bossy administrators. (4)

Before looking into the political motivations behind these assertions, we should first ask if anyone actually takes the position that agriculture and private property mark “an irreversible step toward inequality.” Diamond certainly doesn’t: “Remember again: the developments from bands to states were neither ubiquitous, nor irreversible, nor linear,” he writes early in The World until Yesterday (18). Diamond even uses some of the same language as Graeber and Wengrow, writing, “Traditional societies in effect represent thousands of natural experiments in how to construct a human society” (9). But what is it about the transition from egalitarian bands to larger ranked societies that Graeber and Wengrow find so objectionable? After all, the first complex societies must have emerged from simpler ones, however wide the range of local factors may have been.

The story of agriculture leading to beliefs about private property leading to inequality harks back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, to whom the notion of the virtuous “noble savage” is popularly attributed (though this is an oversimplification of his views). The narrative that is routinely pitted against Rousseau’s is commonly attributed to Thomas Hobbes, who characterized life in a state of nature as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” As poor of a fit as he turns out to be upon close inspection, Diamond serves as a latter-day mouthpiece for Rousseau throughout The Dawn of Everything. Meanwhile, “We can take Pinker as our quintessential modern Hobbesian,” Graeber and Wengrow write (13). For them, though, the two sides of the debate about primordial societies are far less different than most scholars assume. Whether it is the advent of agriculture knocking over the first domino that ultimately ensures domination of the many by the few, or the surly temperament and straitened circumstances of the average hunter-gatherer necessitating the intervention of a government Leviathan to prevent melees, the outcome is the same. Hierarchy is rendered both necessary and inevitable. And that, it turns out, is the worst of the “dire political implications” of the traditional evolutionary sequence.

For Graeber and Wengrow, accepting the traditional formulation that larger scale tends to coincide with more concentrated power means “the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will forever be stomping on our faces” (8). This profound antipathy toward inequality and concentrated political power gels nicely with the strong anti-Western bias prevalent across academia, which is especially pronounced in the humanities and the social sciences. Steven Pinker fell afoul of this bias in 2011when he published The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, which presents copious evidence suggesting that we Westerners are living in an era of unprecedented peace. Following the trendline back into prehistory, Pinker reports startling findings about how common it was to die a violent death, not just before the Enlightenment, but even more so before the rise of the state.

Graeber and Wengrow begin their criticism by pointing out that Pinker overlays his theories about declining violence on the outdated understanding of societal evolution they are working to supplant. Then they get personal:

Since, like Hobbes, Pinker is concerned with the origins of the state, his key point of transition is not the rise of farming but the emergence of cities. “Archeologists,” he writes, “tell us that humans lived in a state of anarchy until the emergence of civilization some five thousand years ago, when sedentary farmers first coalesced into cities and states and developed the first governments.” What follows is, to put it bluntly, a modern psychologist making it up as he goes along. You might hope that a passionate advocate of science would approach the topic scientifically, through a broad appraisal of the evidence—but this is precisely the approach to human prehistory that Pinker seems to find uninteresting. Instead he relies on anecdotes, images and individual sensational discoveries, like the headline-making find, in 1991, of “Ötzi the Tyrolean Iceman.” (13-4)

Turn to the referenced pages in Better Angels, though, and you see it is Graeber and Wengrow who are making things up. The book is chock-full of statistics from scientific sources. Facing one of the two pages that mention Ötzi, which you can find by simply following the index, is a bar graph based on multiple scientific references comparing estimated rates of violence across different types of society. Reading the text, you discover Pinker is not “concerned with the origins of the state” at all; he is interested in those differing rates of violent death between states and other forms of society.

Tellingly, Graeber and Wengrow give the clearest expression of their contempt for Pinker in an endnote to a line criticizing his endorsement of Hobbes’ theories about the causes of violence. Is Pinker’s verdict on Hobbes’ ideas true? “As we’ll see,” Graeber and Wengrow write, “it’s not even close” (13). Here, they direct us to the following note:

If a trace of impatience can be detected in our presentation, the reason is this: so many contemporary authors seem to enjoy imagining themselves as modern-day counterparts to the great social philosophers of the Enlightenment, men like Hobbes and Rousseau, playing out the same grand dialogue but with a more accurate cast of characters. That dialogue in turn is drawn from the empirical findings of social scientists, including archaeologists and anthropologists like ourselves. Yet in fact the quality of their empirical generalizations is hardly better; in some ways it’s probably worse. At some point, you have to take the toys back from the children. (529)

In other words, they are outraged Pinker, a psychologist specializing in language and cognition, had the audacity to even discuss prehistoric societies and their implications for the modern world. But, though they promise a decisive debunking to come—“As we’ll see”—what follows has little if any bearing on Pinker’s thesis.

Now, it is not for me to speculate on the psychological profile of scholars who come down this hard on a colleague when the most effective criticisms they can marshal occupy the hinterlands of legitimate scholarship, somewhere amid the realms of sloppiness, unscrupulousness, and simple dishonesty. But it is noteworthy that Better Angels (odd title for a Hobbesian book) is not even about societal evolution per se, but, as the subtitle relays, the decline in violence over the course of human history. Likewise, Diamond’s The World until Yesterday, again as the subtitle implies, is about what we can learn from traditional societies, not about how such societies scale up. Meanwhile, it is Graeber and Wengrow who are writing a grand revisionist narrative of human prehistory, one called The Dawn of Everything no less.

Before considering which of Hobbes’ ideas Pinker called down the thunder by endorsing, we should note that it is not Pinker who attempts to don Hobbes’ mantle. It is Graeber and Wengrow who try to smother him with it, just as they do Diamond by lumping him together with Rousseau. They insist that if we did a reappraisal of Pinker’s argument, minus the cherry-picking, “we would have to reach the exact opposite conclusion to Hobbes (and Pinker),” by which they mean, “our species is a nurturing and care-giving species, and there was simply no need for life to be nasty, brutish or short” (14). While it is true Pinker credits Hobbes’ insights about the causes of violence, he also goes on to write,

But from his armchair in 17th-century England, Hobbes could not help but get a lot of it wrong. People in nonstate societies cooperate extensively with their kin and allies, so life for them is far from “solitary,” and only intermittently is it nasty and brutish. Even if they are drawn into raids and battles every few years, that leaves a lot of time for foraging, feasting, singing, storytelling, childrearing, tending to the sick, and other necessities and pleasures of life. (56)

Oddly, Graeber and Wengrow cite evidence of early peoples caring for the sick and injured as a counter to Pinker’s findings about prehistoric violence. In other words, they aggressively prosecute Pinker for crimes anyone with ten minutes and access to the source material can see he never committed.

Things only get worse when Graeber and Wengrow discuss Pinker’s use of the Yąnomamö of southern Venezuela and northern Brazil to illustrate a scenario called the “Hobbesian trap,” or more technically as the “security dilemma.” Imagine a homeowner with a gun encountering a burglar in his house who is also visibly packing. Even though the homeowner may not want to kill anyone over what may be an act of desperation, there is no guarantee the burglar won’t shoot first. Likewise, the burglar may not be apt to kill people who are simply defending their homes, but there is no guarantee the homeowner won’t shoot first. Shooting first becomes the most rational option for both. As Pinker explains,

People in nonstate societies also invade for safety. The security dilemma or Hobbesian trap is very much on their minds, and they may form an alliance with nearby villages if they fear they are too small, or launch a preemptive strike if they fear an enemy alliance is getting too big. One Yąnomamö man in Amazonia told an anthropologist, “We are tired of fighting. We don’t want to kill anymore. But the others are treacherous and cannot be trusted.” (46)

It should be noted here that this is the only mention of the Hobbesian trap in relation to the Yąnomamö in the whole of Better Angels; Graeber and Wengrow, however, insist Pinker cherry-picks this society to support his wider application of a Hobbesian framework.

Graeber and Wengrow go on to botch both their definition of the security dilemma and the explanations of Yąnomamö violence offered by Pinker and Napoleon Chagnon, the anthropologist whose writings inform his theory. Graeber and Wengrow write that

the Yanomami are supposed to exemplify what Pinker calls the “Hobbesian trap,” whereby individuals in tribal societies find themselves caught in repetitive cycles of raiding and warfare, living fraught and precarious lives, always just a few steps away from violent death on the tip of a sharp weapon or at the end of a vengeful club. (16)

Pinker in fact treats revenge as a separate cause of violence, though he does describe cycles of raids and counterraids as the common outcome. Graeber and Wengrow apply the term Hobbesian trap as a catch-all description of a violent society to reinforce their characterization of Pinker as a carrier of Hobbes’ torch. Though, as we’ve already seen, Pinker specifically writes that nonstate peoples were not always “a few steps away from a violent death.”

The closest Graeber and Wengrow get to addressing the statistics underlying Pinker’s argument is to point out that “compared to other Amerindian groups, Yanomami homicide rates turn out average-to-low” (15). This is an odd point, since Graeber and Wengrow earlier in the section claim Pinker cherry-picked the Yąnomamö because they are particularly violent. And both Pinker and Chagnon themselves point to the relatively higher rates of violence among other groups to counter such charges of cherry-picking and exaggeration from other critics. Graeber and Wengrow go on to claim that

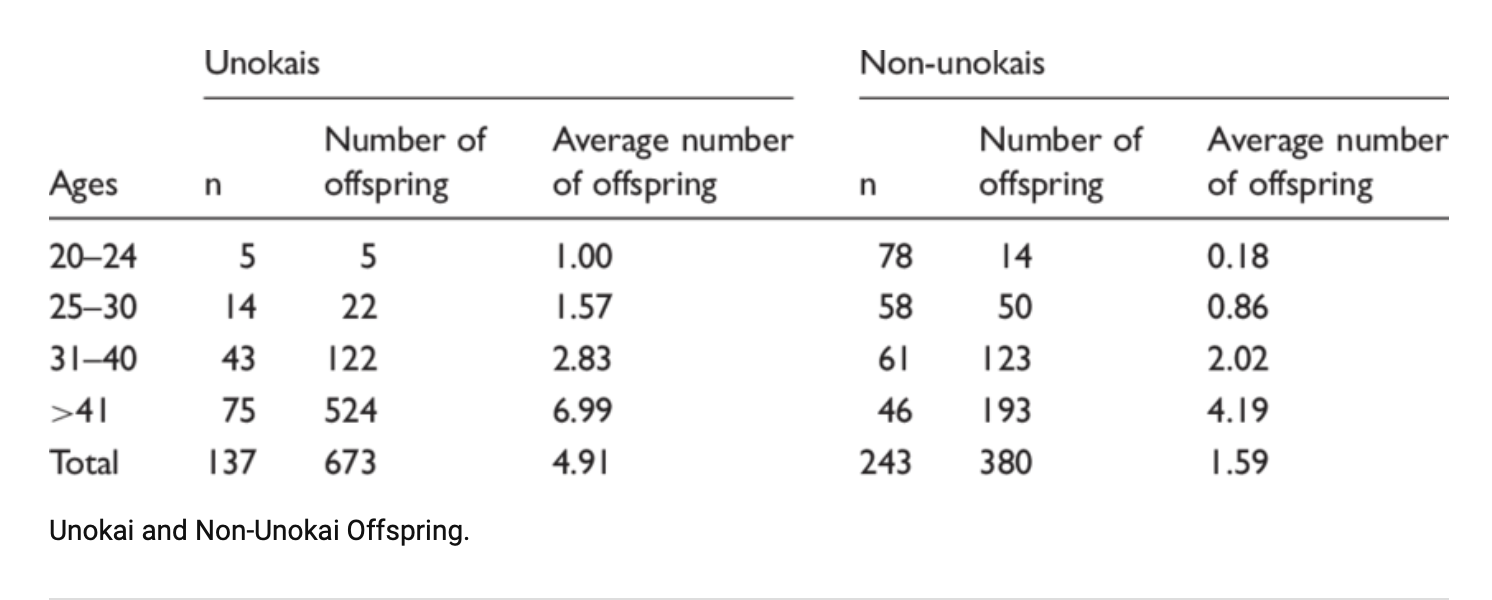

Chagnon’s central argument was that adult Yanomami men achieve both cultural and reproductive advantages by killing other adult men, and that this feedback between violence and biological fitness—if generally representative of the early human condition—may have had evolutionary consequences for our species as a whole. (16)

This is in fact what Chagnon’s critics view as the main takeaway of his work. What he was really contending in the article Graeber and Wengrow cite was not that the Yąnomamö show us how humans may have evolved to be violent, but that Yąnomamö violence was motivated by individual and family interests—what biologists call “inclusive fitness”—and not by a desire for some other village’s valuable resources. In other words, ironically, Chagnon was challenging some of the same notions about the role of farming and private property that Graeber and Wengrow take Diamond and Pinker to task for accepting, even though those two really don’t endorse these notions either.

The publication of Better Angels made Pinker persona non grata among many social scientists and leftist commentators because it reintroduces the idea of progress in Western history. Specifically, Pinker attributes the most dramatic dips in the trendlines representing violence to some of the ideas and values that came to prominence during the Enlightenment. Unfazed by the backlash to Better Angels, Pinker doubled down in 2018 by publishing Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, which shows numerous other trendlines all suggestive of people living longer, safer, healthier, even happier lives than their ancestors—all contrary to the dismal view of life in modern states put forth by Graeber and Wengrow.

Pinker ascribes these improvements to the implementation of ideas that took hold and blossomed in 17th and 18thcentury Europe. Graeber and Wengrow respond by pointing to Pinker’s presumed politics (because, remember, their impact on his reasoning is inevitable), asking, if Pinker wants to portray himself as a rational centrist,

why then insist that all significant forms of human progress before the twentieth century can be attributed only to that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as “the white race” (and now, generally, call themselves by its more accepted synonym, “Western Civilization”)? (17)

The shift from Pinker’s real argument to Graeber and Wengrow’s straw man entails turning the focus from the ideas of the Enlightenment to the race of the people who first embraced them as a larger cultural package. But Pinker does not attribute the progress he reports to Western civilization as a whole—which would make no sense given its long history—but to a single current that began to run through it at a certain point in that history.

Graeber and Wengrow’s not-so-subtle accusation of racism is a predictable instantiation of the activists’ imperative to default to the presumed victims’ perspective—which likely also motivated them to make the case that the Enlightenment was largely indigenous peoples’ idea. It is this same imperative which infuses with venom the taboo against suggesting that anything coming from the West might somehow be better than what is on offer in non-Western societies or that anything coming from non-Western societies might somehow be worse. Graeber and Wengrow explain the problem thus:

Insisting, to the contrary, that all good things come only from Europe ensures one’s work can be read as a retroactive apology for genocide, since (apparently, for Pinker) the enslavement, rape, mass murder and destruction of whole civilizations—visited on the rest of the world by the European powers—is just another example of humans comporting themselves as they always have; it was in no sense unusual. What was really significant, so this argument goes, is that it made possible the dissemination of what he takes to be “purely” European notions of freedom, equality before the law, and human rights to the survivors. (17-8)

Not only is Pinker a racist by their lights; he is also an apologist for genocide, slavery, rape, and mass slaughter. This would be outrageous if true, but as we’ll see, it’s not even close.

The sleight of hand here is again to conflate Pinker’s celebration of the specific Enlightenment values he lists in his subtitle with the whole of Western civilization. It would be difficult for anyone embracing the ideals of reason, science, and humanism to justify something so abhorrent as the transatlantic slave trade—which is not to say no one ever tried. To say that some people, who happened to live in Europe, took up a certain set of ideas, which would eventually lead to improved lives for those carrying on their tradition, does nothing to excuse the atrocities committed by other people, who also happened to be living in Europe at the time. “For one thing,” Pinker writes in Enlightenment Now,

all ideas have to come from somewhere, and their birthplace has no bearing on their merit. Though many Enlightenment ideas were articulated in their clearest and most influential form in 18th-century Europe and America, they are rooted in reason and human nature, so any reasoning human can engage with them. That’s why Enlightenment ideals have been articulated in non-Western civilizations at many times in history. (29)

Recall Graeber and Wengrow claim Pinker’s argument is that “‘purely’ European notions” are responsible for making the world a better place, when in fact Pinker explicitly argues the opposite. (Are those supposed to be scare quotes surrounding the word “purely”?) And Pinker is under no illusion that every European embraced the Enlightenment with equal fervor. He writes,

But my main reaction to the claim that the Enlightenment is the guiding ideal of the West is: If only! The Enlightenment was swiftly followed by a counter-Enlightenment, and the West has been divided ever since. (29)

In Better Angels, Pinker does consider the possibility that recent biological evolution played a role in declining violence among Europeans, but he dismisses the theory as both implausible and unnecessary. No matter, Graeber and Wengrow need to make the issue about race so they can comfortably dismiss Pinker as a racist, so that’s what they claim—the actual substance of Pinker’s arguments be damned.

Graeber and Wengrow continue their criticism of Pinker’s thesis by asserting that the only way to compare two societies is to give people a chance to experience both and then let them choose which one they would prefer to live in. They go on to assure readers that “empirical data is available here, and it suggests something is very wrong with Pinker’s conclusions.” Here’s what they mean:

The colonial history of North and South America is full of accounts of settlers, captured or adopted by indigenous societies, being given the choice of where they wished to stay and almost invariably choosing to stay with the latter. This even applied to children. Confronted again with their biological parents, most would run back to their adoptive kin for protection. By contrast, Amerindians incorporated into European society by adoption or marriage, including those who… enjoyed considerable wealth and schooling, almost invariably did just the opposite: either escaping at the earliest opportunity or—having tried their best to adjust, and ultimately failed—returning to indigenous society to live out their last days. (19)

Empirical evidence that European settlers and indigenous people alike “almost invariably” prefer to live in indigenous societies—that would be some data set. Of course, people may choose to live in a society with a shorter life-expectancy and other drawbacks for a host of reasons that bear little relation to the general quality of life. For instance, they may have fallen in love. Or they may be wanted for a crime back home. Still, the finding would be suggestive. We have to wonder who collected and analyzed the original sources and what criteria they used to score the cases. How did they ensure the sample was representative of the total population of captives and former captives? How large is this sample? And by “almost invariably,” do they mean north of 90%, or some even higher percentage?

To get just a portion of the statistics on pre-state violence Graeber and Wengrow pretend he never bothered to investigate, Pinker relied on a paper published in the journal Science. That means it was rigorously peer-reviewed, its methods scrutinized, its math checked and doublechecked. What prestigious journal was Graeber and Wengrow’s source published in? It turns out the source they cite was never published in a journal at all; it was rather a doctoral thesis submitted in 1977 by a PhD candidate named Joseph Norman Heard—which isn’t to disparage it. The thesis, titled “The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” makes for fascinating reading. The first thing you notice is that it is a qualitative, not quantitative analysis, which already casts doubt on Graeber and Wengrow’s account. The second thing you notice is that, at least in the abstract, Heard reports nothing like what Graeber and Wengrow claim. Heard summarizes a section examining the factors that go into determining whether a captive became assimilated thus,

It was concluded that the original cultural milieu of the captive was of no importance as a determinant. Persons of all races and cultural backgrounds reacted to captivity in much the same way. The cultural characteristics of the captors, also, had little influence on assimilation. (vi)

We are still in the introductory material for the paper, and already we see the author’s own conclusion is that whatever is going on in these cases, it is not what Graeber and Wengrow suggest. Assimilation is not about people sampling two cultures and voting with their feet. So what was going on? According to Heard, “It was concluded that the most important factor in determining assimilation was age at the time of captivity.” Heard reports that children captured before puberty almost always became assimilated—recall Graeber and Wengrow’s line, “This even applies to children”—while those captured after puberty usually wanted to return to their society of origin. This was the case for settler and indigenous children alike.

In other words, Graeber and Wengrow’s approach to refuting Pinker’s case for progress is first to severely distort his actual position to support their charge of racism, and second to grossly misrepresent a doctoral thesis from over forty years ago so that it appears to undermine a claim of general superiority Pinker never made. Time to take the toys back from the children indeed. The one part of Heard’s paper that cites actual numbers reports that of one sample of 750 captured settlers, 92 were killed, and 60 became completely assimilated. Taking 658 as the number who had the opportunity to choose, we’re left with a mere 9% who remained with their captors. For Graeber and Wengrow, nine out of a hundred equates to “almost invariably.” Even if you add every last one of the 1500 missing captives in the report with no further record to the list of the assimilated—a move there is no justification for—you are still left with 28% who were not fully assimilated.

When historian Daniel Immerwahr pointed out in a review for The Nation that the characterization of Heard’s findings in The Dawn of Everything is “ballistically false,” Wengrow took to twitter to try to salvage the point by highlighting individual lines and suggesting that Heard considered too small of sample—apparently forgetting this was the source he and his coauthor chose to cite. For good measure, he intimates that Immerwahr got tripped up because he only read the abstract. Nowhere in the thread, however, aside from a block quote from Benjamin Franklin, does he point to any part of Heard’s paper that could in any way be construed as justification for his and Graeber’s claim that captives “almost invariably” became completely assimilated. Wengrow concludes his thread by reminding his followers what’s at stake: “for context, our point here was to refute Pinker’s suggestion that any sensible person would prefer Western civ to life in (what he calls) ‘tribal’ societies.” No citation is provided to point readers to where Pinker makes this suggestion.

The expression straw man refers to the underhanded rhetorical tactic of challenging an argument the person being challenged never made. One of the most common examples involves treating claims about statistical trends as if they were about ironclad laws. To strawman Diamond and Boehm’s point that mobile hunters and gathers tend to be egalitarian, Graeber and Wengrow insist their position is that all hunters and gathers must be egalitarian. Then they point to exceptions and pretend they have refuted the point. Usually, straw men bear at least some resemblance to the actual argument—enough to create an illusion of fairness and accuracy. So, does the term still apply when one scholar claims another argues a point diametrically opposed to the point that was actually made? Or do we need a stronger term? What do we call it when scholars creatively misinterpret a source so it appears to undermine another scholar’s thesis when in fact it does no such thing? Archeologist Michael E. Smith calls Graeber and Wengrow out for their use of “empty citations,” an expression for when “works are cited merely to lend an aura of support for an argument, when in fact they contain no empirical support.” Historian David Bell meanwhile worries that their discussion of the indigenous influence on Enlightenment thinking “comes perilously close to scholarly malpractice.” When scientists fabricate results from their experiments, we call it fraud. Is that too harsh a verdict in this case?

In light of Graeber and Wengrow’s stated political concerns, I think the best term for what they’ve done with The Dawn of Everything is propaganda. While it is true that every scholar who writes a book has political concerns—including Diamond and Pinker—the important question is whether those concerns take precedence over truth-seeking. If your priority is finding and sharing the truth, then you will report evidence that runs counter to your preferred political narrative honestly and accurately. If pushing that narrative is your priority, on the other hand, then you will be apt to neglect or distort any source that challenges it. When the goal is to influence people to adopt moral or political positions, what does it matter if your case is based on straw men or ad hominem attacks? Thus, it is not that Graeber and Wengrow come out and state that at least one of their issues is political that calls for applying the label—though that is a red flag. It is rather the conjunction of the stated political concern with the execrable, single-note scholarship on display throughout The Dawn of Everything that earns it the descriptor.

What were Graeber and Wengrow hoping to achieve with their propaganda? First, having observed that works like The World until Yesterday and Enlightenment Now have captured the public imagination like few books on such weighty topics ever do, they wanted to recapture the audience for those books for assimilation into their own society of archeologists and anthropologists—the ones with the correct politics and priorities. They open their book with a quote from Carl Jung about living in the right time for a “metamorphosis of the gods.” The study of human prehistory is indeed going through some upheaval in response to many of the dramatic discoveries Graeber and Wengrow describe in The Dawn of Everything, and it seems they saw this as an opportunity to firmly establish their own paradigm before the rival one takes hold anew.

To understand why they might have been motived to do this, suffice to say the fields of anthropology and archeology are divided into rival camps, one that prioritizes science and truth-seeking in the tradition of Thomas Huxley, and another that prioritizes political reform—or at least carries on assured that truth-seeking is always perfectly compatible with a reform agenda. Scholars in this latter camp tend to believe the status quo in the West is as oppressive and unjust today as at any point in its history, and far more so than most other societies around the world. Graeber and Wengrow write,

If something did go terribly wrong in human history—and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did—then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence. (502)

That is why they bristle at Pinker’s observations about progress, and why they treat field workers like Chagnon who report on indigenous violence as suspect. That is why Graeber was so incredulous of those “neoliberal/conservative” numbers he tweeted about. What this means is that Graeber and Wengrow are effectively sending the message: Don’t listen to these guys who stole our toys, listen to us, or at least listen to people who think like us, the ones who know the West is evil and our only hope lies in dismantling its institutions.

Second, as they clearly state, Graeber and Wengrow want to persuade readers that concentrated political power is neither necessary nor inevitable for modern states—a lesson we would naturally learn from indigenous peoples of the past if we could only stop viewing them as “cardboard stereotypes” (21) in the tradition of Rousseau and Hobbes. “What is the purpose of all this new knowledge,” they ask in the conclusion, “if not to reshape our conceptions of who we are and what we might yet become?” (525). Political reform is so important to them that they list “the freedom to shift back and forth between social structures” (133) or “the freedom to create or transform social relationships” as one of three “primordial freedoms” (426). The crux of their argument for the possibility of a less politically unequal large-scale society is that such societies existed in prehistory, or at least it looks like they may have. If the people living in these societies could manage it, maybe, why can’t we?

The main unexamined assumption at the heart of The Dawn of Everything is that hierarchy and concentrated political power can only ever exist to the detriment of the people. Pinker, for instance, advocates pacificism and liberal democracy, not heavy-handed authoritarian rule. But that’s not radical enough for Graeber and Wengrow. Insofar as Western history moves in a particular direction, they can see no alternative to it being from freedom to domination, which is ironic considering their complaints about the traditions of Rousseau and Hobbes. In addition to the freedom to experiment with social arrangements, they list the freedom to move to another location and the freedom to disobey orders among the primordial liberties we in the West have lost. By the freedom to relocate, they mean that indigenous peoples could count on a friendly welcome when they arrived at a new place, though the only evidence for this is artifacts in one place originating in another and the existence of the same clan names across wide swaths of the continents. Graeber and Wengrow spend little time weighing the possibility that some travelers met with different fates than others, and they make no effort to quantify how many people exercised this freedom in prehistory versus in today’s modern societies. As for the third freedom, while they suggest we in the West have been trained in obedience, even in modern Western societies, you find a great deal of ambivalence toward authority figures, for reasons Boehm eloquently explains. Witness our fraught relationship with police.

Maybe the difference Graeber and Wengrow mean to highlight is that modern Westerners must obey certain authority figures in certain contexts, whereas in prehistory people were free to disobey anyone at any time. But was that really ever the case? Conspicuously absent from their list of primordial freedoms are the freedom to choose an occupation and the freedom to choose a spouse. And never mind the opportunities that would simply never be on offer, like choosing a major at a university or choosing to go on sabbatical to write a doorstop lamenting lost freedoms. Diamond and Pinker write in terms of tradeoffs when moving from one type of society to another. “Traditional societies may not only suggest to us some better living practices,” Diamond writes in The World until Yesterday, “but may also help us appreciate some advantages of our own society that we take for granted” (9). But for Graeber and Wengrow, the modern West is bad because of domination and oppression, while the world beyond its influence—which is mostly in prehistory—may have some unsavory elements, but as a whole was just better. If you have any doubts, they might direct you to Heard’s 1977 thesis, though they wouldn’t want you to read it too closely.

A lot of us share Graeber and Wengrow’s desire for a more widely and diversely distributed governing apparatus, but merely describing the ability to create an entirely new social arrangement as a freedom presents us with a problem: who exactly enjoys this freedom? And who grants it to them? The simplest example they give of creating a social arrangement is the promise, and indeed any individual can make a commitment to another individual. But what about the other person in this arrangement? Is this person not free to discount the promise? If the promise entails some sort of reciprocal gesture or behavior, no one is free to make the other person play along. Additionally, what form does the promise take? Do you invoke a deity? A monarch? These are all matters determined by the cultural context, and no lone individual is free to change the culture on his or her own.

Graeber and Wengrow repeatedly insist scale has no necessary implications for decision-making structures, but is it not logically the case that the larger the society the less influence any individual can have, because that individual would have to persuade however many more people to adopt any new convention? The authors are clearly irritated by Diamond’s argument that increasing scale must be correlated with concentrated decision-making, and by Pinker’s suggestion that disinterested third-party institutions are necessary to curb cycles of violence, but they never effectively engage with the basic logic. Instead, they again and again point to this or that archeological site, insisting the absence of palaces and the similarity of the dwellings means people there were equal and had no kingly rulers. Or they point to this or that indigenous American confederacy we only know about through patchy records or folk histories. (As an interesting counterexample to Graeber and Wengrow’s complaints about Westerners not being able to imagine indigenous peoples coming up with any good ideas for social arrangements, the Iroquois “Great League of Peace” is generally acknowledged as an inspiration for the US Constitution.) But, while for them the most important fact is that these more enlightened governing institutions existed, for the rest of us the big question is how exactly they functioned. How are we to follow their examples, after all, if we have no idea how they solved problems of communication and coordination? What happened when a significant bloc of people opposed an otherwise collective decision? How did they address factionalism and polarization? (You get the sense from reading The Dawn of Everything that the authors have never in their lives had a conversation with a MAGA republican—or for that matter a conservative of any stripe.)

Graeber and Wengrow take a step toward acknowledging these difficulties in their discussion of traditional Basque settlements, which are some of the few egalitarian communities in the modern world. Houses in these settlements are arranged in circular patterns, and each household has a set of obligations to the houses on both sides, with the effect that “no one is first, and no one is last” (295). But, as Graeber and Wengrow point out,

such “simple” economies are rarely all that simple. They often involve logistical challenges of striking complexity, resolved on a basis of intricate systems of mutual aid, all without any need of centralized control or administration. (297)

In the next paragraph, though, they write, “There is no reason to assume that such a system would only work on a small scale.” Of course, such a system could possibly work on a larger scale—say with tens of thousands of households—but, despite their proclamation to the contrary, there is good reason to believe such a complex system would be unlikely to arise and persist. It’s the same reason complex lifeforms are unlikely to burst into existence in the absence of slightly simpler precedents. Anyway, is a complex set of obligations to surrounding neighbors any less of a curb to freedom than a set of laws devised by a bureaucratic government?

The archeologist Michael E. Smith, whose work on Teotihuacan Graeber and Wengrow cite in their book, characterizes their arguments about scale and urban institutions as “a serious example of ignoring prior relevant research.” Again and again throughout The Dawn of Everything, the authors attempt to dismiss theories about increasing stratification and concentrated power by tracing them back to outdated—often colonialist—theories from bygone eras. But as Smith explains,

Graeber and Wengrow want to establish that the decentralized decision-making and social freedoms common in small groups and small-scale societies can also work at an urban scale…The idea that population size and density have strong effects on urban society and organization is not just an assumption or ideological belief, as Graeber and Wengrow suggest. It is, rather, one of the most strongly supported empirical findings of urban research. (4)

Smith cites sources from a range of fields to support this assertion, but his most compelling example comes from an annual event that the organizers originally planned based on anarchistic principles.

Aerial view of Burning Man Festival

The Burning Man Festival began as 35 people on a beach in California in 1986. By 2019, attendance had grown to 80,000. Sometime in the late 90s, the organizers started to see problems arising. As festival planner Rod Garrett explains,

We got to a point where I saw people becoming irrationally angry with each other and with the city. It occurred to me that this might be an effect of overpopulation, and that we’d hit some tipping point where people were no longer comfortable.

This is a gathering of people as likeminded, at least with regard to their aversion to arbitrary constraints on their radical self-expression, as you’re likely to encounter in such large numbers. And even among this group of avowed idealists, a threshold of population density was eventually reached that necessitated the imposition of rules and greater efforts at organization. Could these new rules have been arrived at collectively? Not without first coming up with a way to gather 80,000 opinions and a method for transforming them into actionable plans. What the organizers did instead was to create the rules themselves—the few dictating to the masses.

Intriguingly, Graeber himself seems to have experienced the difficulties on the other side of this dynamic firsthand. We have already seen how difficult it can be to maintain harmonious societies at largescale, but the other challenge for egalitarian decision-making is that you have to find a way to prevent ambitious individuals from accumulating power. In a footnote to a discussion of their three proposed forms of power—control of violence, control of information, and personal charisma—the authors reveal that at least one of them (probably Graeber) has witnessed groups struggling to keep their members from acquiring one or another of them. They write,

This again is easy to observe in activist groups, or any group self-consciously trying to maintain equality between members. In the absence of formal powers, informal cliques that gain disproportionate power almost invariably do so through privileged access to one or another form of information. If self-conscious efforts are made to pre-empt this, and make sure everyone has equal access to important information, then all that’s left is individual charisma. (587)

This footnote comes dangerously close to an admission of how difficult egalitarianism is to establish and preserve—“almost invariably”—since putting checks on individual authority in one form leaves open opportunities of gaining other forms of influence.

As replete as The Dawn of Everything is with ax-grinding and unscholarly shenanigans, as out of date as the supposedly conventional thinking it seeks to topple turns out to be, and as quixotic as the reform agenda the authors hope to galvanize probably is, we must still ask if there might be a scientific baby at risk of being thrown out with the propagandistic bathwater. Unsurprisingly, the parts of the book I personally enjoyed most tended to be the least polemical. I found the discussion of “culture areas” and “schismogenesis”—whereby one society consciously defines itself and its values in opposition to another neighboring society—both riveting and largely plausible. “One problem with evolutionism,” Graeber and Wengrow write, “is that it takes ways of life that developed in symbiotic relation with each other and reorganizes them into separate stages of human history” (446). That is a remarkable—and potentially fruitful—insight. And it is true that, while scholars like Boehm leave more room for exceptions to the egalitarian model of nomadic hunter-gatherers than Graeber and Wengrow let on, the range of variation is revealing itself to be far greater than previously imagined (but probably still not as great as Graeber and Wengrow suggest).

Indeed, if a trace of impatience can be detected in my presentation, the reason is this: the question of how archeological sites like Göbekli Tepe and Poverty Point, with their massive scale, large earthen mounds, and monumental stonework, all built by hunter-gatherers, should rewrite our understanding of human social evolution is both fascinating and hugely consequential. That is why it was so disappointing to open The Dawn of Everything and find the authors riding their hobbyhorses and airing their petty grievances instead of genuinely engaging with the relevant research. Rather than offering readers their expert take on the science behind these mesmerizing discoveries, Graeber and Wengrow saw fit to exploit the intrinsic wonder to gin up support for their unscientific agendas. Though it just may have something to do with my own political concerns, I personally can’t wait until Jared Diamond, or someone writing in his tradition, takes up the topic anew.

As for the political agenda in The Dawn of Everything, I may be less radical than Graeber and Wengrow, as I share Pinker’s conviction that while we should continue working to ensure marginalized peoples enjoy the same opportunities and protections as the most privileged among us, we also have a responsibility to both honor and safeguard the progress all the activists of past generations worked so hard to secure by exercising their own primordial right to experiment with new social arrangements. Who are we to sneer at their successes and narcissistically toss aside the fruits of their efforts? The most important starting point for any reform initiative is a clear-eyed understanding of the current reality, one that people outside the movement can be confident is based on our best methods for getting at the truth. That’s why it’s so important to keep science as separate from activism as humanly possible. Whether we are talking about anthropologists, climate scientists, or infectious disease specialists, we simply cannot afford for the view of scientists as mere members of this or that special interest group to gain any more traction than it already has. Science may have resisted committing suicide to date, but every time the public discovers an agenda driving research on important issues, its trust suffers one more potentially fatal blow.

***

Also read:

Just Another Piece of Sleaze: The Real Lesson of Robert Borofsky's "Fierce Controversy"

“The World until Yesterday” and the Great Anthropology Divide: Wade Davis’s and James C. Scott’s Bizarre and Dishonest Reviews of Jared Diamond’s Work

Violence in Human Evolution and Postmodernism’s Capture of Anthropology

Why Timothy Snyder Lied about Jonathan Gottschall and Steven Pinker in The New York Times

Why would a public intellectual of Timothy Snyder’s stature accept the commission to review a book he couldn’t bring himself to read, only to go on to write a review that’s so caustic, contemptuous, careless, and dishonest that anyone who gets around to picking up Jonathan Gottschall’s book will see at a glance that the reviewer is sanctimonious, superior, mean-spirited, and completely full of shit? Something interesting must be happening behind the scenes to make Snyder so reckless with his reputation for honest scholarship, something urgent enough to overshadow any concern for his integrity. What might that something be?

My first thought after reading Timothy Snyder’s review of Jonathan Gottschall’s The Story Paradox in The New York Times was, “Jeez, did Gottschall sleep with this guy’s wife or something?” Snyder’s own most popular book, On Tyranny, is written as a series of lessons and includes chapters titled, “Remember Professional Ethics” and “Believe in Truth.” Yet something in The Story Paradox bothered him so much he jettisoned his own professional ethics by distorting—and flat-out lying about—its contents, and he did it in perhaps the most prestigious newspaper in the English-speaking world. The most likely explanation for the review’s copious errors is that Snyder never actually read the book; he instead flipped through it looking for points he could arrange into a narrative of his own about the evil Gottschall and his ridiculous ideas about the dangers of story. But why would a professor of history at Yale, one who’s garnered a modicum of fame over the past few years through his appearances on multiple news outlets, one whose book has been on the bestseller lists for the past five years—why would this guy suddenly forget all his own warnings about the dangers of propaganda so he could go on to create some of his own?

With his review, Snyder creates a fictional version of Gottschall and his book that bear a striking non-resemblance to their real-life counterparts. The version of The Story Paradox you’ll discover if you actually read the book has Gottschall acknowledging the much-touted benefits of becoming immersed in a good story, including a boost in empathy, particularly for the types of people represented by the protagonist. He goes on to point out, however, that the flipside is also true: stories often inspire suspicion, fear, and hatred as well. The haunting example he cites in the introduction is the Tree of Life killer, who believed an ancient story about evil Jews trying to take over the country, believed it so sincerely that he went to a synagogue with a gun and murdered 11 people, wounding several others. As effectively as storytellers seduce us into partisanship on behalf of their protagonists, along with real-life people embroiled in similar struggles, they also tempt us into indulging our darkest impulses when dealing with antagonists, which in fiction means cheering on the heroes as they mete out brutal justice, and in reality can mean cheering on violence against people thought to be in the same camp as those antagonists—or even actively participating in such violence.

Snyder’s made-up version of the book, on the other hand, has Gottschall fumbling through a bunch of books before concluding “that no one has ever undertaken his subject, the ‘science’ of how stories work.” Gottschall’s actual gripe in the relevant section near the end of the book (190) was that story science is absent from psychology textbooks; he writes in the introduction, “Today a broad consortium of researchers, including psychologists, communications specialists, neuroscientists, and literary ‘quants,’ are using the scientific method to study the ‘brain on story’” (13). No matter—Snyder goes on to whip up a tale of a quixotic scholar, ironically trapped in his own self-stroking story even as he warns of the dangers of becoming trapped in your own stories, ignorant or disdainful of every past scholar’s contribution, obsessed with statistics and algorithms to the point where he doesn’t even bother to read the great works of literature he’s subjecting to his brand of cold-blooded analysis, all so he can arrogantly declare he’s discovered insights that have been perfectly obvious to every real scholar of literature for decades. Oh, and his efforts somehow pander to the powerful while exacerbating economic inequality—or at least failing to offer keys for how to fix it. Gottschall himself satirized Snyder’s review in a postmortem for Quillette, writing,

my reviewer began by dispensing with effete norms against ad hominem argument to spin a tale of a cartoon heel named Jonathan Gottschall—a fool who sees himself as an intellectual colossus. Gottschall also has an unfortunate mental condition that causes him to shout mad, dangerous things. All history is useless, Gottschall shouts, before going on to hypocritically cite a bunch of history books. Down with the humanities, Gottschall cries, and down with humans too! Up with Zuckerberg! Up with big data and the robot overlords! Down with the wretched of the earth! Up with the big evils of unrestrained capitalism and “power”!

What stands out about Snyder’s fictional characterizations when placed alongside the relevant passages in the book is that there’s almost no chance he arrived at his defamatory view of Gottschall through any good faith effort at understanding his positions. The review is a deliberate smear.

Whose perspective?

Snyder’s take on the subject matter of The Story Paradox is just as absurdly off-base. At one point, he suggests that Gottschall writes “creepily” about a young girl in a fictional snippet he composed himself, adding that “The story will be different when not narrated from a place of complacent omnipotence, for example if it is told from the perspective of the woman.” This is precisely the type of innuendo—see, Gottschall is a creepy misogynist—journalism students are taught to avoid (or used to be anyway). There’s also the small problem that Gottschall in fact did write the vignette from the girl’s perspective. This mistake is hardly the exception. The review’s central points are, to a one, based on bonkers misconstruals. Snyder somehow even managed to miss the book’s central thesis; he complains that Gottschall “promises a paradox in his title, but none is forthcoming.” I could quote the passage in the introduction where Gottschall describes the paradox in detail, but you don’t need to read beyond the subtitle to get the idea: How Our Love of Stories Builds Societies and Tears Them Down.

Based on the number of errors and the quality of the prose, it looks as though Snyder devoted no more than a few hours to scanning the book and scribbling his takedown. Along with the myriad mischaracterizations, his review is filled with choppy non sequiturs and odd solecisms, like when he claims, “Little is original in his analysis. His notion that stories tell us arose out of the structuralist anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss in the 1950s.” His notion that stories tell us what? And how can Snyder know if Gottschall’s analysis is original if he can’t accurately state what that analysis entails? Even if we ignore the poor grammar, Snyder’s point is just silly. He’s referring to Lévi-Strauss’s theory of a universal language of myth, which the anthropologist posited operates on a dynamic juxtaposition of binary opposites. Though Gottschall does describe a “universal story grammar,” at no point in The Story Paradox does he put forth the idea that opposing binaries lie at the heart of effective stories, unless you count good guys versus bad guys, which wasn’t at all what Lévi-Strauss had in mind. The only similarity is that both Lévi-Strauss and Gottschall are interested in universals. (Also recall that this charge of unoriginality is coming from a guy who achieved notoriety among the politically left-leaning for comparing the opposition leader to Hitler.)

Here’s Snyder’s take on the theory put forth in The Story Paradox: “The universal story hard-wired into our brains is, says Gottschall, one in which everything gets worse until it gets better.” Apparently, Snyder thinks that was Lévi-Strauss’s theory as well. He goes on to recite a list of stories that don’t have happy endings, supposedly exposing the absurdity of Gottschall’s argument. Now, Gottschall does at one point cite a research finding that stories which get worse and worse until a happy resolution occurs at the end are far more popular than those with other plot structures. But he never claims that structure is universal (102). What he says about the universal structure of stories is this:

The universal grammar of storytelling has, I propose, at least two major components. First, everywhere in the world stories are about characters trying to resolve predicaments. Stories are about trouble. Stories are rarely about people having good days. Even comedies, though they often end happily, are usually about people gutting through bad days—often the very worst days of their whole lives. Second, as corny as it may at first sound, stories tend to have a deep moral dimension. Although sophisticated novelists, historians, or filmmakers may deny that they’d ever sink to expressing anything like a “moral of the story,” they’ve never stopped moralizing for a moment. “The poets,” says Nietzsche, “were always the valets of some morality.”

Stipulated: If you ransack your brain, you’ll be able to name exceptions. But they will be exceptions that prove the rule—statistical outliers dominated by experimental works like Finnegan’s Wake. On the other hand, maybe it seems obvious to you that stories are this way. But academic literary theorists would mostly deny it. And, if you think about it, it’s not a bit obvious that stories should be this way. Many of us might expect to find storytelling traditions where stories mostly function as escape pods into hedonistic paradises where pleasure is infinite and moral trespass in unknown.

We never do. (100)

It would be bad enough if Snyder had merely relied on the cheap strawman tactic of turning Gottschall’s qualified point about a statistical trend into an absolutist claim that can be refuted with reference to a few exceptions, but Snyder doesn’t even refer to the right section of the book in his effort to convince us of the weakness of Gottschall’s theory. (That, Professor Snyder, is what happens when you skim instead of reading.)

Okay, so what’s going on here? Why would a public intellectual of Snyder’s stature accept the commission to review a book he couldn’t bring himself to read, only to go on to write a review that’s so caustic, contemptuous, careless, and dishonest that anyone who does get around to picking up Gottschall’s book will see at a glance that the reviewer is sanctimonious, superior, mean-spirited, and completely full of shit? Something interesting must be happening behind the scenes to make Snyder so reckless with his reputation for honest scholarship, something urgent enough to overshadow any concern for his integrity.

What might that something be?

Gottschall sees a clue in Snyder’s outsized objection to his endorsement of the work of Steven Pinker. The section in The Story Paradox where Gottschall refers to Pinker is only a few paragraphs long, but Snyder devotes almost as much space in his short hit piece in the Times to a seemingly damning critique of Pinker’s findings. This prompts Gottschall to posit,

At the bottom of the reviewer’s contempt is an allergy to two traits Pinker and I share. We both seek to bring a scientific mindset to traditional humanities questions, and we both feel obliged to question the ideological excesses not only of the right wing, but also of the intellectual left.

I think Gottschall is correct on both points, but if Snyder simply despised these men’s positions on a few hot-button issues, he could have addressed them honestly. Instead, he does two things legitimate scholars aren’t supposed to do: he makes his criticisms personal, and he bases those criticisms on a deliberate and gross misreading of the work under review.

So, what made Snyder think Gottschall and his book must be so bad they didn’t deserve a fair hearing? Let’s look at both factors Gottschall identifies, beginning with ideological excesses, and see if they adequately account for what Snyder wrote in his hatchet job.

Leftist Ideology at Elite Universities

In an ideal world, we could take book reviews at face value. Scholars would assess each other’s ideas and writing, then relay to the rest of us their expert take on what a book covers, what informs its perspective, and how successfully the author achieves her goals. Unfortunately, we don’t live in that world. Instead, with ideological positions taken in advance, reviewers all too often take it as their mission to campaign for or against the author of the book under consideration. And the rhetoric they use in the service of these campaigns has far more in common with what you hear on cable news than in any reason-based scholarly debate.

The sad reality is that we live in an age when large swaths of academia have come under the sway of a political ideology which holds that ideas must be weighed, not by their truth value, but by their imagined consequences. What an author intends to convey to readers, in other words, is far less important than the impact these academics insist the work will have on the wider society. Surveys designed to explore the distinction between liberals and leftists find that the latter tend to define themselves in terms of their anti-capitalism and their radical antipathy toward the current societal order, with all its supposedly oppressive systems and structures. Liberals on the other hand are far more likely to define themselves according to their advocacy of choice and their embrace of science. Leftists understand liberals endorse many of the same progressive social reforms they do, but they fault liberals for wanting incremental, as opposed to radical change, often, the leftists insinuate, because the current order affords liberals some form of privilege they want to safeguard. Another way of looking at this is that while liberals want to tweak the system to move us ever closer to a world where everyone enjoys the same freedoms and opportunities, leftists see the system as inherently oppressive, so they want to tear it down and establish an altogether new one.

Here’s how that precept plays out in academic disputes. The core assumption of the leftist ideology is that, whether we know it or not, whether we’re willing to acknowledge it or not, we are all engaged in a struggle either to maintain the political and social status quo or to dismantle it. As linguist John McWhorter describes this foundational tenet:

Battling power relations and their discriminatory effects must be the central focus of all human endeavor, be it intellectual, moral, civic or artistic. Those who resist this focus, or even evidence insufficient adherence to it, must be sharply condemned, deprived of influence, and ostracized.

The work of any author, leftists would have us believe, must therefore be understood in the context of this struggle to tear down the institutions and structures that empower some at the expense of others—whether that author has any desire to comment on that struggle or not. That’s why you get this bizarre passage in Snyder’s review of The Story Paradox:

Part of Gottschall’s tale of himself is that his views will offend the powerful. Yet his own account of the world does nothing to challenge the status quo. He treats political conflict only as culture war, a view that is more than comfortable for those in power. His most feared enemy, he says, are left-wing colleagues; he portrays their thinking as entirely about culture. One would think, reading him, that left and right had nothing to do with economic equality and inequality, a subject Gottschall ignores.

Though he claims to have read “2,400 years of scholarship on Plato’s ‘Republic,’” Gottschall misses the famous point in Book IV about the city of the rich and the city of the poor. In a country where a few dozen families own as much wealth as half the population, the opportunities for storytelling are unevenly distributed. Gottschall has nothing to say about this. He believes that we live in a “representative democracy” in which the stories told by the powerful simply reflect our own stories. No need, then, to think about the Electoral College, campaign finance, gerrymandering, or the suppression and subversion of votes. Gottschall offers not a challenge to the powerful, but a pat on the back.

Recall that Gottschall’s book is about the effects of storytelling, not economics. Essentially, Snyder is criticizing The Story Paradox for what it’s not about. Nowhere in the book does Gottschall come down in favor of the political left or the right, as the book is not directly concerned with politics. He does express concern over the lack of viewpoint diversity in journalism and academia, as nearly everyone working in these fields is politically left of center, but that comes right after a long section about the dangerous, if entertaining, absurdity of “the Big Blare,” his epithet for Trump, who he won’t even name. Nowhere in the book does he express the view that “the stories told by the powerful simply reflect our own stories,” but he does discuss how the left has adopted “a history from the point of view of the enchained, the plundered, and all the restless ghosts of the murdered” (136).