THE STORYTELLING APE

Essays and Book Reviews on Evolutionary Psychology, Anthropology, the Literature of Science and the Science of Literature

There’s a lot not to like about the AMC series Mad Men, but somehow I found the show riveting despite all of its myriad shortcomings. Critic Daniel Mendelsohn offered up a theory to explain the show’s appeal, that it simply inspires nostalgia for all our lost childhoods. As intriguing as I always find Mendelsohn’s writing, though, I don’t think his theory holds up.

Brooks Landon’s course is well worth the effort and cost, but he makes some interesting suggestions about what constitutes a great sentence. To him, greatness has to do with the structure of the language, but truly great sentences—truly great writing—gets its power from its role as a conveyance of meaning, i.e. the words’ connection to the real world.

Being in a kayak on the creek, away from civilization even while you’re smack in the middle of it, works some tricky magic on your sense of time. This is my remembrance and reflection on one particular trip with a friend.

I aced the verbal reasoning section of the GRE the first time I took it. It ended up, not being the worst thing that ever happened to me, but… distracting. Eleven years later, I had to take the test again to start trying to make my way back into school. How could I compete with my earlier perfection?

Woolf’s struggle with her mother, and its manifestation as Lily’s struggle with Mrs. Ramsay, represents a sort of trial in which the younger living woman defends herself against a charge of selfishness leveled by her deceased elder. And since Woolf’s obsession with her mother ceased upon completion of the novel, she must have been satisfied that she had successfully exonerated herself.

Your efforts to place each part into the context of the whole will, over time, as you read more stories, give you a finer appreciation for the strategies writers use to construct their work, one scene or one section at a time. And as you try to anticipate the parts to come from the parts you’ve read you will be training your mind to notice patterns, laying down templates for how to accomplish the types of effects—surprise, emotional resonance, lyricism, profundity—the author has accomplished.

Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson’s central finding in his research on expert achievement is that what separates those who attain a merely sufficient level of proficiency in a performance domain from those who reach higher levels of excellence is the amount of time devoted over the course of training to deliberate practice. But, in a domain with criteria for success that can only be abstractly defined, like creative writing, what would constitute deliberate practice is difficult to define.

It’s nothing new for people with a modicum of familiarity with psychology that there’s an illusory aspect to all our perceptions, but in reality it would be more accurate to say there’s a slight perceptual aspect to all our illusions. And one of those illusions is our sense of ourselves.

The appeal of stories like Horton Hears a Who! and A Gathering of Old Men lies in our strong human desire to see people who are willing to cooperate, even at great cost to themselves, prevail over those who behave only on their own behalves.

To say Edgar Allan Poe had a defiant streak is an enormity of understatement. He had nothing but contempt for many of his fellow writers, and he seemed at times almost embarrassed to be writing for the types of audiences who loved his most over-the-top stories. He may have pushed some of his stories to the extreme and beyond in the spirit of satire, but that’s not how readers took them. It just may be that at some point he started sending coded messages to his readers, confident most of them would be too stupid to pick up on them.

Much of the impact of Hemingway’s work comes from the mystique surrounding the man himself. Hemingway was a brand even before his influence had reached its zenith. So readers can’t really come to his work without letting their views about the author fill in the blanks he so expertly left empty. That’s probably why feelings about it tend to be so polarized.

Conventional wisdom after the Columbine shooting was that the perpetrators had lashed out after being bullied. They were supposed to have low self-esteem and represented the dangers of letting kids go about feeling bad about themselves. But is it possible at least one of the two was in fact a narcissist? Eric Harris definitely had some fantasies of otherworldly grandeur.

The theories put forth by evolutionary critics, particularly the Social Monitoring and Volunteered Affect Theory formulated by William Flesch, highlight textual evidence in Joyce’s story “The Dead” that undermines readings by prominent Lacanians—evidence which has likely led generations of readers to a much more favorable view of Joyce’s protagonist.

Our rebel cry against consumerism has long since been packaged and sold back to us. So while reading we’re not learning about others, certainly not learning about ourselves, and at the same time we’re fueling the machine we set out to sabotage.

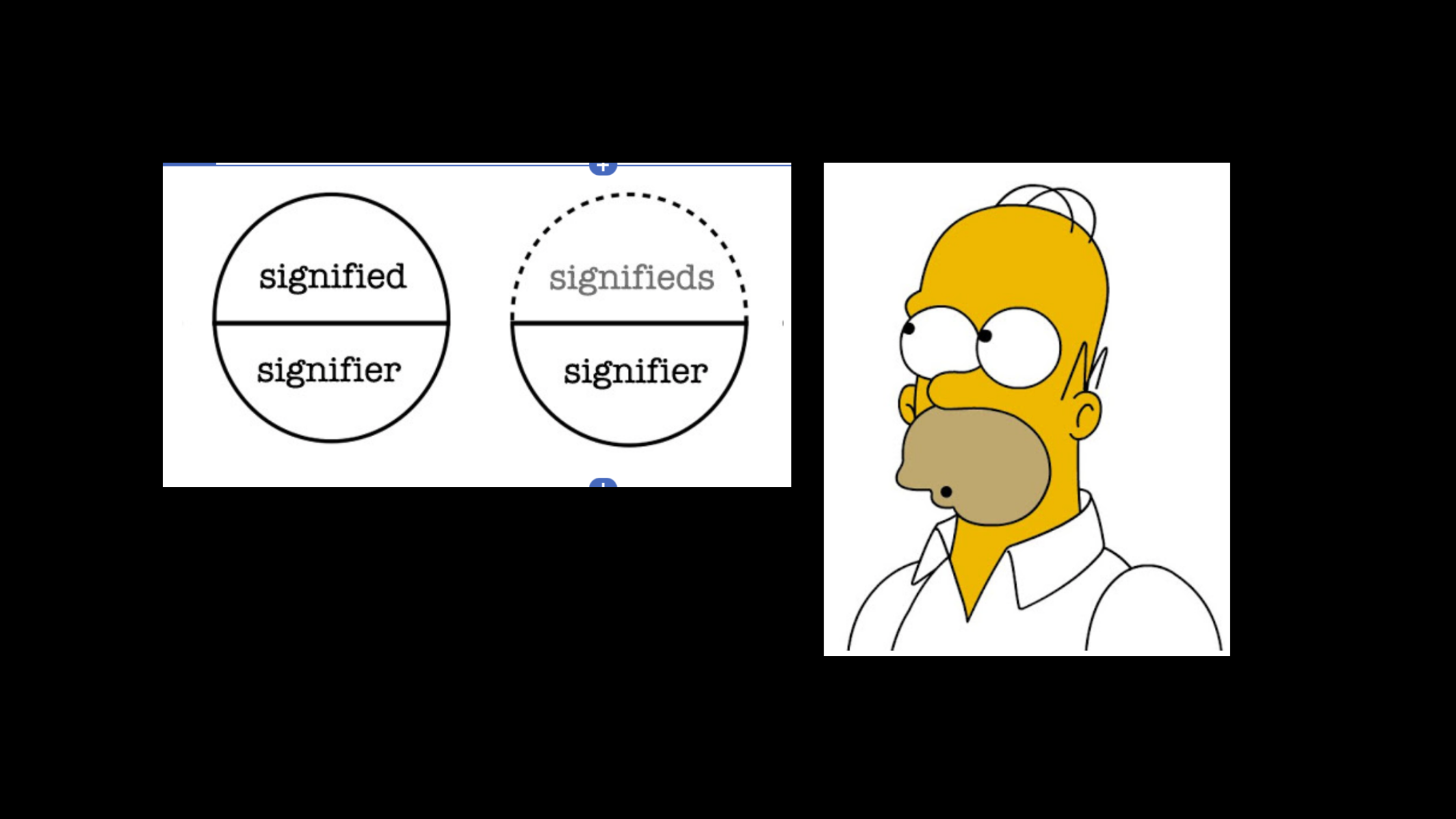

Poststructuralists believe that everything we see is determined by language, which encapsulates all of culture, so our perceptions are hopelessly distorted. What can be done then to arrive at the truth? Well, nothing—all truth is constructed. All that effort scientists put into actually testing their ideas is a waste of time. They’re only going to “discover” what they already know.

The dominant epistemology in the humanities, and increasingly the social sciences, is postmodernism, also known as poststructuralism—though pedants will object to the labels. It’s the idea that words have shaky connections to the realities they’re supposed to represent, and they’re shot through with ideological assumptions serving to perpetuate the current hegemonies in society. As a theory of language and cognition, it runs counter to nearly all the evidence that’s been gathered over the past century.

Written at a time in my life when I wanted to argue politics and religion with anyone who was willing—and some who weren’t—this essay starts with the observation that when you press a conservative for evidence or logic to support their economic theories, they’ll instead tell you a story about how their own personal stories somehow prove it’s possible to start with little and beat the odds.

Aschenbach’s fate in the course of the novel can be viewed as hinging on whether he will be able, once he’s stepped away from the lonely duty of his writing, to establish intimate relationships with real humans, as he betrays a desperate longing to do. When he ultimately fails in this endeavor, largely because he fails to commit himself to it fully, Mann has the opportunity to signal to his readers how grave the danger is that every artist, including Thomas Mann, must face as he stands at the edge of the abyss.

What does the black cat in Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Black Cat” symbolize? The old man who’s murdered in “The Tell-Tale Heart” had one eye that stared intensely at the narrator. The black cat, Pluto, in the other story likewise ends up with a single eye. This is Poe poking at fun at his half-blind readers. What does that tell us? Well, Pluto, it so happens, isn’t merely the god of the underworld. Pluto was also a god of wealth. Poe had to appeal to the half-blind to earn his wealth.

There’s a lot of weird theorizing about what the movie Fight Club is really about and why so many men find it appealing. The answer is actually pretty simple: the narrator can’t sleep because his job has him doing something he knows is wrong, but he’s so emasculated by his consumerist obsessions that he won’t risk confronting his boss and losing his job. He needs someone to teach him to man up, so he creates Tyler Durden. Then Tyler gets out of control.