READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

In the Crowded Moment atop the Fire Wave

A reflection on time and friendship, the product of reading a bunch of Cormac McCarthy, going through a breakup, and going out west to visit some national parks with old friends.

Emily had continued ahead of them all along the trail until she was out of sight. Steven had fallen behind, likewise now occluded by the towering red wall of rock. He was sure for a while after he began following Stacy that Steven would be coming along. But when he stepped up onto an escarpment and climbed a ways to a higher vantage he looked and saw no one on the trail behind him. The way Emily plunged forth with no concern for keeping apace the rest of the group and the fact that now Steven was showing a similar disregard gave him the sense that some deadly tension was building between them. But, then, hadn’t they been like this for as long as they’d been together? He turned and continued along a route above the sandy track on the rock surface, thinking of the rough-grained unyielding folds as ripples caught in some time-halting spell as they oozed along, the lower tiers melting out from beneath those stacked above, the solid formation melting from the bottom up.

Marching at a pace to overtake Stacy, he watched the dull blood-stained bands of the undulating sandstone pass through the space immediately before his feet and thought of Darwin striding across the volcanic rock surface of an island in the Galapagos, Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology still resonating in the capacious chambers of his dogged mind, the sense taking hold more solidly that the solid earth beneath his feet had once been, and may again at any moment be, a flowing emblem of impermanence. Later, when the Beagle docked in Chile, the coast only hours before blasted by an earthquake and subsequent tsunami, Darwin, stepping onto the rocky shore, smelled putrefying fish. The quake had lifted what had moments before been seafloor up into the open air, and, seeing the remains of all the stranded marine creatures, he suddenly understood the provenance of the fossil shells and crustaceans he’d found high in the mountains, thousands of feet above sea level.

A hundred and fifty years later, it seems like such a simple deduction. To advance our understanding of geology or evolution today, he thought, you would have to be much more subtle than that. And yet, he wondered, how many people think of moments in history, the earthshaking conception of earthshattering theories, as they traverse rock formations like these? What do most people think of when they’re walking along this trail? He looked up and saw how the distant mountains bursting up into the sky gave scope to the vast distances, making of the horizon a symbol of the tininess of these individual human bodies tossing imperceptibly about on the tide of eternity, precipitating a vertiginous dropping away of identity, obliteration before the shock wave of detonated timescales.

Stacy and Emily were still far enough ahead, and Steven far enough behind, that he had the trail to himself. Darwin just isn’t relevant to anyone, he thought. The concentrated heat of the toppling afternoon sun was momentarily chased over the corrugated sandstone by a chill. You can live your whole life, he thought, be moderately happy, and never have to think of evolution or geological timescales even once—hell, you may even be happier that way. And you, he thought to himself, you may have a type of passion teachers think is just delightful—until you let it loose to savage their own lessons. But most people, most of the time, would rather not have to take anything that seriously. Examine the underpinnings to a point. Allow for doubts and objections to a point. The point where having to think about what it could mean isn’t as exciting as it is scary. The way you do it makes people uncomfortable. It made your ex want to kill you.

He had the thought—before deciding that he wouldn’t be thinking about her anymore this trip—that his ex couldn’t make that final compromise. Whatever disagreement they’d had was years past, but, even though her ability to articulate what this insurmountable barrier in her heart consisted of went no further than “I can’t forgive you,” even though she’d meet the idea with her own detonations, he knew that last unbudgable bit of incompatibility, the ultimate deal-breaker, had everything to do with her gathering recognition that their two worldviews, once so distant, their separate territories so fiercely guarded, had moved steadily closer over the years—and it wasn’t his that was undergoing the displacement. She needed that one refuge of holding out. So I got to be right, he thought. But what’s it worth if I’m alone? And anyway, much as everyone assumes the contrary, I could give a fuck about being right.

Then there’s Stacy’s easy social grace—masterful really. She has a fine sense of everyone’s perspective, an impressive memory for everyone’s preferences, and, when in doubt, she simply fills the void with the surging energy of her character. Her charms are even such as can accommodate the intensity of his skepticism and passion for science’s refining crucible. What would she be thinking right now? Where she’s going to live in the coming weeks? Whether she’ll be able to find a job in Charlotte? How much she’s going to miss the poor boys she drives so crazy? Or maybe she too is wondering how the rock came to have such clearly demarcated bands, what accounts for the red hues—iron?—and what it means that our human lifespans scarcely even register on the timescale of geology. As vivacious and loquacious as she is, she’s always had an impressively developed inner life. Still, he remembers her nudges under the table that first night he was in L.A., debating with her friends during their apartment gathering about the virtues, or lack thereof, of SSRIs, those nudges which effectively said, “Don’t do that now—don’t be you,” though that last part was more in keeping with what his more recent ex might’ve said.

As he covered more distance yet failed to overtake the women ahead of him on the trail, he felt increasingly and pleasantly placeless, but the discomfort at leaving Steven behind for all this time began to disrupt the flow his thoughts. Still, he assured himself, it isn’t like any of us will have the chance to pop over again some other time. Steven could’ve come along; it isn’t my responsibility to make sure no one gets stuck waiting for the others—a task that between them Steven and Emily seemed to be going out of their way to make impossible. His mind went back to the party, to Corina, the pretty blonde, talking about how people give her directions out of Compton whenever she drives through to meet with the troubled teens she tries to help. He scanned his memory for evidence that she was offended or unsettled by anything he said. No, she was incredulous—how could someone say antidepressants don’t work? It was such a foreign idea. But she seemed to enjoy grappling with it, batting it back. She seemed exhilarated to be in the presence of someone so confidently misguided. And fine, he would have said, let’s see how far down the rabbit hole you can go before you start to panic. No, he decides, it really is bullshit, all that about me hurting people. The worst that can be said is that I ruined the mood—and even that isn’t true. If anything, I brought some unexpected excitement.

When he first stepped into the apartment and was introduced to Corina, he put some added effort into answering the question about what it is he does in Fort Wayne, setting his current job within the context of his aspirations, perhaps making it seem more exciting than it really is, as if it were just a way station along the path to his career as a novelist. Speaking of your occupation as a vocation, telling a story about how you came to do what you’re doing and how it will lead to you doing something even more extraordinary—it was something he’d ruminated on as he made the trip westward. All the strangers making small talk on the planes and in the airports, and that question, “What do you do?”, so routine. One or two words couldn’t suffice as an answer. The two words may as well be, “Dismiss me.” Telling a story, though, well, everyone appreciates a good story. You may forget a mere accountant, or programmer, or copywriter, but everyone loves a protagonist.

Maybe, he thinks now, you can do something similar when it comes to your beliefs and your way of thinking and debating and refusing to shy away from disagreements. Present it in the context of a story—how you came to think the way you do—with a beginning, middle, and end.

He imagines himself on a first date saying, I always talk about the importance of science, and I feel it’s often necessary to challenge people on beliefs that they’ve invested a lot of emotion in. So a lot of people assume I’m heartless or domineering—that I get off on proving how smart I am. The truth is I’m so sensitive and so sentimental that half the time I’m disgusted with myself for being so pathetic. If I’m calculating, it would be more like the calculations of someone with second degree burns lowering himself into a tub of ice water. That sensitivity, though, that receptiveness, it’s what makes me so attentive and engaged. I go into these trances when I read or even when I’m watching movies or shows. People are impressed with how well I remember plots and lines from stories. People in school used to ask how I did it. There wasn’t any trick. I sure as hell didn’t apply any formula. I just took the stories seriously—I couldn’t help but take them seriously. The characters came across as real people, and I cared about them. The plots—I knew they weren’t real of course—but in those moments when you’re really into it, they’re real in their own way. It’s like it doesn’t matter if they’re real or not. And that connection I have to novels and shows, you know, it’s like in school they try to tell you that’s not how you should read and they tell you all this bullshit about how you’re supposed to analyze them or deconstruct them. All I can say is when I realized how utterly fucking stupid all that literary theory crap is—it was like this huge epiphany. I felt so liberated. And today a lot of the arguments I get into are with people who want to take this or that writer to task for some supposed sexism or racism, or for not toeing the line of some brain dead theory.

But the other part of it is that I still remember being sixteen and realizing that the Catholicism I was brought up with was the purest nonsense, nothing but a set of traditions clung to out of existential desperation and unthinking habit. What made that so horrible for me, again, was that up till then I had taken it so seriously. I wasn’t a bible thumper or anything. But I prayed every night. I really believed. So when it came crashing down—well, I can’t describe how betrayed I felt. I remember wondering why no one tried harder to get at the truth before they all conspired to foist this idiocy on so many children. The next big disillusionment came when my friends and I started watching the Ultimate Fighting Championships. At the time, I’d been taking tae kwon do and karate for over four years in a couple of those strip mall dojos MMA guys talk about with such disdain these days. Watching those fights, guys actually going in there and trying beat the shit out each other, I saw—even though I admit it took me a while to accept it—most of the stuff I’d been learning so assiduously all those years was next to worthless. It was like, oh well, at least you learned some discipline and stayed in shape. Yeah, but I could have been learning muay thai or jujitsu. The thing is, when you go in for this type of nonsense, it’s not just your thing. It affects other people. Religious people teach religion to their kids. They proselytize to anyone who’ll listen. Those charlatan karate teachers, they take people’s money. They give them a false sense of control—not to mention wasting their fucking time.

Then there were the two years in college when I had my heart set on being a clinical psychologist. At the time, everyone just knew childhood trauma was at the root of almost all mental illness. I listened to that Love Lines show on the radio where Dr. Drew and Adam Corolla interrogated the women who called in until they broke down and admitted they’d been abused as children. Then, the summer before my senior year, I start digging into the actual science. Turns out the sexual abuse everyone is so sure fucks kids up for life—its effects can’t even be distinguished from those of physical abuse or neglect. There’s almost no evidence that those childhood traumas lead to psychological issues later in life. Repressed memories? Total bullshit. If you think you underwent some process of recovering long-forgotten memories of sexual abuse you suffered as a child, what you were really doing was going through a ritual induction into a bizarre, man-hating, life-ruining cult. And I was graduating from college at just about the time in the late 90s when all the false accusations and wrongful imprisonments were coming to light. Oh, and did I mention that the first girl I fell in love with—the woman up ahead of me on the trail right now—I couldn’t touch her for years because I was so worried about the harm it might cause, that lost time of my late teens and into my twenties. My mind so full to capacity with all that ridiculous feminist pseudo-psychology. Instead of coming on to her, I waited for her to initiate, and she wondered what the hell was wrong with me since all the while I kept insisting I didn’t want to be just friends. Oh, the awakenings I had in store, rude and otherwise, when it came to women and desire.

Then there was a brief flirtation with new age ideas after I took a course on Religion and Culture where the teacher assigned the fucking Celestine Prophecy as a text book—and she treated all the claims as if they were real. Luckily, Carl Sagan’s Demon-Haunted World was recommended by one of my anthropology teachers, so I read it soon afterward. I wanted to leave a copy in the Religion and Culture teacher’s mailbox. Sagan’s book was what showed me, not what ideas I should believe in, but how I could go about finding out which ideas were most likely to be true. That book changed my perspective on society and conventional wisdom in general. I think most people assume if a bunch of teachers tell you something and if enough people believe it there must be something to it. But some ideas, most ideas, sometimes I think nearly all ideas but a precious few are just plain wrong no matter who or how many people believe them. What I couldn’t have known then is how much that kind of thinking would alienate me.

He stopped, having arrived at the top of a large rise which dropped off precipitously before him. He chuckled, thinking, yeah, maybe you better not say all that on a first date. Looking across to another, somewhat lower rise, he saw Stacy leveling her iPhone for a picture. Two tall and slender women, attired in form-fitting apparel like Stacy’s, were likewise taking turns getting pictures of each other on the various peaks and mounds. He watched the girls, turned back to the jagged mountains on the distant horizon, like the spine of some scarcely corporeal monster cresting the surface of a sand-crusted sea, the air separating the countless miles as perceptibly invisible as the freshly polished crystal of a priceless timepiece, and he thought about how hospitable all the world has become to us humans. Without the cars and the roads and the ready stores of water, this desert would appear so differently to them. In all likelihood, they would even lose something of their humanity, becoming vicious to adapt to the precariousness and harsh brutality of a less trustworthy denizenry.

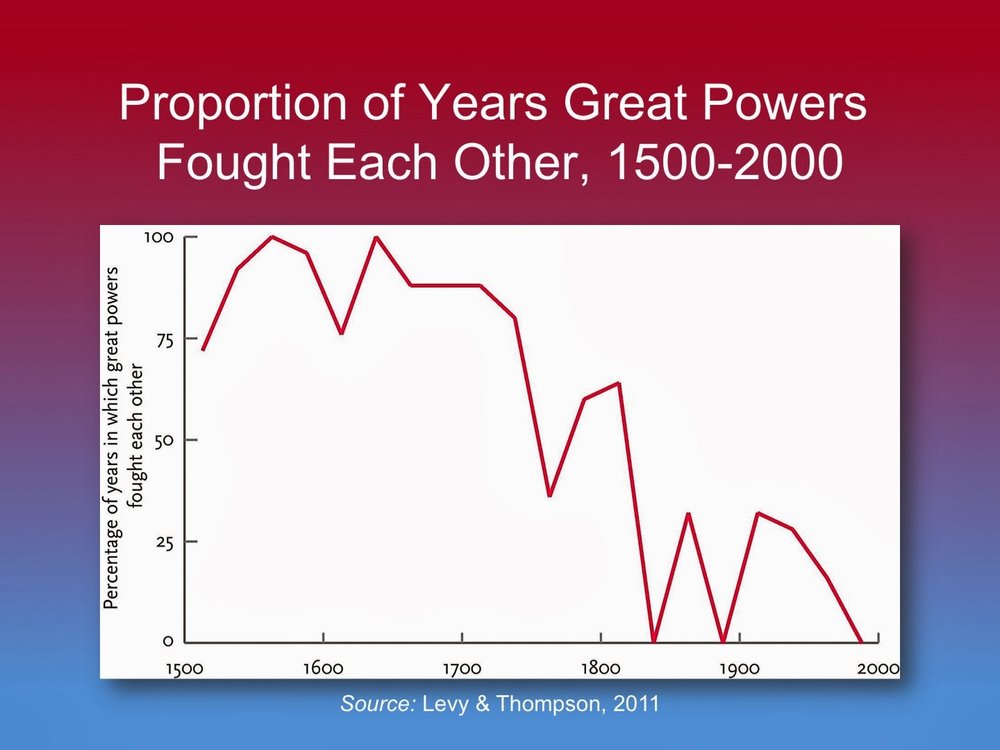

He imagined roving bands of Native Americans, then government-sponsored cavalries, cowboys, thieves, marauders, so many varieties of deadly men, barely human. We’ve had to build up, on such a flimsy foundation, a space for men to be more civilized, more peaceful, less desperate. And somehow what we—or our forebears, also mostly men—created has succeeded to such a stupid degree we take it enough for granted that whole schools of thought have grown up to lament the evils of civilization. The truth is, before civilization came, as civilization was still busy coming, there was probably enough bloodshed in this region that the pink of iron glowing in these seasonally layered bands under our feet may have leeched into the rock after leaking from the endless variety of wounds sustained by human flesh.

Looking over the rim of the bulging rock, he saw it rolling away severely to reveal a drop of several hundred feet. And he was surprised to realize, for the third time in two days, the instinctual anchor preventing him from taking a step, and another, toward that abrupt curving back and away of the rough surface, it had either vanished or simply never existed. He felt his weight pulling against the spongy grip of the soles of his shoes while his breaths continued slow and his heart beat softly on. It wasn’t until turning back to check once again if he could see Steven from this elevated vantage that he felt an impulse to back away from the downward curve. If he was to let himself fall, he’d only do so eyes forward.

Self-conscious now, he glanced about for Stacy and the handful of other people milling about the outcroppings, nestled pockets, and rolling protuberances of ancient rock. What are we all looking for in these travels and treks to otherworldly places? We’re looking for inspiration, calling forth moments, invoking the powers of transcendence, pushing ourselves forward into what we hope are those periods of our lives when it seems like we’re finally becoming who in our dreamlife hearts we always believed we would be. Set the world alight with enchantment and endless possibility. And we’ve all had those experiences where we’ve met someone, or undertaken some project, or set off to some faraway destination—and all our lives seemed in flux and we were moving at last toward that state of being when we could relax, be ourselves, but work and strive meaningfully at the same time. Usually, though, we miss them. The quake’s upheaval threatens more than it promises. We can’t appreciate these periods in our lives while we’re living them because we’re still caught up in the time and the transformation that occurred previous to this one. Attachments are like habits that way. You could wait till the end of time and they’d never extinguish on their own. Your only hope is to replace the old ones with new ones. But since no love you have can ever match the poignancy of the loves you’ve lost, no civilization lives up to the golden accomplishments of the one that’s vanished, you live looking back, boats against the current and all that. Or, knowing all this, you wait. And you look out. And you wonder all the while if there’s something more you should be doing to bring about that next period of becoming who you are, worrying that you may have already used up all the ones you had coming.

He walked down the rounded surface, on the side he’d come up, feeling purged, emptied of some burden of long-accustomed ache, as if it had drained from his blood into the banded stone beneath his soft-soled shoes. Drops in time, echoes like living breathing beings, the absent people in our minds. Exes, old friends, Darwin, roving bands of savage men—they have life, existence independent now from the bodies housing their own autonomous searchings and wanderings. Their echoes forever pull and impact us, scour our flesh and turn us inside out—flaring with the red heat of rage and longing and protectiveness and abandonment and loss. These emotions they call forth with their spectral gestures, their faces, their words, they never cease, even with physical absence. Each prod, each tug, each blow gets recorded and replayed forever, the dynamic of our interactions carrying on even when we’re alone, drowning out all the other beckonings at the doorstep of our hearts.

“Where the hell is Steven?”

He looks up from where he’d been searching for footholds to see Stacy startlingly close to where he’d finally landed two-footedly in the sand. “I don’t think he’s coming.” His felt snot wetting his mustache, the unaccountable allergic outflow that had been plaguing them all for the past two days. “He’s really missing out.”

Also read:

THE TREE CLIMBER: A STORY INSPIRED BY W.S. MERWIN

And

Gone Girl and the Relationship Game: The Charms of Gillian Flynn's Amazingly Seductive Anti-Heroine

Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” is a brilliantly witty and trenchant exploration of how identities shift and transform, both within relationships and as part of an ongoing struggle for each of us to master the plot of our own narratives.

The simple phrase “that guy,” as in the delightfully manipulative call for a man to check himself “You don’t want to be that guy,” underscores something remarkable about what’s billed as our modern age of self-invention. No matter how hard we try, we’re nearly always on the verge of falling into some recognizable category of people—always in peril of becoming a cliché. Even in a mature society characterized by competitive originality, the corralling of what could be biographical chaos into a finite assemblage of themes, if not entire stories, seems as inescapable as ever. Which isn’t to say that true originality is nowhere to be found—outside of fiction anyway—but that resisting the pull of convention, or even (God forbid) tradition, demands sustained effort. And like any other endeavor requiring disciplined exertion, you need a ready store of motivation to draw on if you’re determined not to be that guy, or that couple, or one of those women.

When Nick Dunne, a former writer of pop culture reviews for a men’s magazine in Gillian Flynn’s slickly conceived, subtly character-driven, and cleverly satirical novel Gone Girl, looks over the bar he’s been reduced to tending at the young beauty who’s taken a shine to him in his capacity as part-time journalism professor, the familiarity of his dilemma—the familiarity even of the jokes about his dilemma—makes for a type of bitingly bittersweet comedy that runs throughout the first half of the story. “Now surprise me with a drink,” Andie, his enamored student, enjoins him.

She leaned forward so her cleavage was leveraged against the bar, her breasts pushed upward. She wore a pendant on a thin gold chain; the pendant slid between her breasts down under her sweater. Don’t be that guy, I thought. The guy who pants over where the pendant ends. (261)

Nick, every reader knows, is not thinking about Andie’s heart. For many a man in this situation, all the condemnation infused into those two words abruptly transforms into an awareness of his own cheap sanctimony as he realizes about the only thing separating any given guy from becoming that guy is the wrong set of circumstances. As Nick recounts,

You ask yourself, Why? I’d been faithful to Amy always. I was the guy who left the bar early if a woman was getting too flirty, if her touch was feeling too nice. I was not a cheater. I don’t (didn’t?) like cheaters: dishonest, disrespectful, petty, spoiled. I had never succumbed. But that was back when I was happy. I hate to think the answer is that easy, but I had been happy all my life, and now I was not, and Andie was there, lingering after class, asking me questions about myself that Amy never had, not lately. Making me feel like a worthwhile man, not the idiot who lost his job, the dope who forgot to put the toilet seat down, the blunderer who just could never quite get it right, whatever it was. (257)

More than most of us are comfortable acknowledging, the roles we play, or rather the ones we fall into, in our relationships are decided on collaboratively—if there’s ever any real deciding involved at all. Nick turns into that guy because the role, the identity, imposed on him by his wife Amy makes him miserable, while the one he gets to assume with Andie is a more complimentary fit with what he feels is his true nature. As he muses while relishing the way Andie makes him feel, “Love makes you want to be a better man—right, right. But maybe love, real love, also gives you permission to just be the man you are” (264).

Underlying and eventually overtaking the mystery plot set in motion by Amy’s disappearance in the opening pages of Gone Girl is an entertainingly overblown dramatization of the struggle nearly all modern couples go through as they negotiate the contours of their respective roles in the relationship. The questions of what we’ll allow and what we’ll demand of our partners seem ever-so-easy to answer while we’re still unattached; what we altogether fail to anticipate are the questions about who our partners will become and how much of ourselves they’ll allow us the space to actuate. Nick fell in love with Amy because of how much he enjoyed being around her, but, in keeping with so many clichés about married life, that would soon change. Early in the novel, it’s difficult to discern just how hyperbolic Nick is being when he describes the metamorphosis. “The Amy of today,” he tells us, “was abrasive enough to want to hurt, sometimes.” He goes on to explain,

I speak specifically of the Amy of today, who was only remotely like the woman I fell in love with. It had been an awful fairytale reverse transformation. Over just a few years, the old Amy, the girl of the big laugh and the easy ways, literally shed herself, a pile of skin and soul on the floor, and out stepped this brittle, bitter Amy. My wife was no longer my wife but a razor-wire knot daring me to unloop her, and I was not up to the job with my thick, numb, nervous fingers. Country fingers. Flyover fingers untrained in the intricate, dangerous work of solving Amy. When I’d hold up the bloody stumps, she’d sigh and turn to her secret mental notebook on which she tallied all my deficiencies, forever noting disappointments, frailties, shortcomings. My old Amy, damn, she was fun. She was funny. She made me laugh. I’d forgotten that. And she laughed. From the bottom of her throat, from right behind that small finger-shaped hollow, which is the best place to laugh from. She released her grievances like handfuls of birdseed: They are there, and they are gone. (89)

In this telling, Amy has gone from being lighthearted and fun to suffocatingly critical and humorless in the span of a few years. This sounds suspiciously like something that guy, the one who cheats on his wife, would say, rationalizing his betrayal by implying she was the one who unilaterally revised the terms of their arrangement. Still, many married men, whether they’ve personally strayed or not, probably find Nick’s description of his plight uncomfortably familiar.

Amy’s own first-person account of their time together serves as a counterpoint to Nick’s narrative about her disappearance throughout the first half of the novel, and even as you’re on the lookout for clues as to whose descriptions of the other are the more reliable you get the sense that, alongside whatever explicit lies or omissions are indicated by the contradictions and gaps in their respective versions, a pitched battle is taking place between them for the privilege of defining not just each other but themselves as well. At one point, Nick admits that Amy hadn’t always been as easy to be with as he suggested earlier; in fact, he’d fallen in love with her precisely because in trying to keep up with her exacting and boundlessly energetic mind he felt that he became “the ultimate Nick.” He says,

Amy made me believe I was exceptional, that I was up to her level of play. That was both our making and our undoing. Because I couldn’t handle the demands of greatness. I began craving ease and averageness, and I hated myself for it. I turned her into the brittle, prickly thing she became. I had pretended to be one kind of man and revealed myself to be quite another. Worse, I convinced myself our tragedy was entirely her making. I spent years working myself into the very thing I swore she was: a righteous ball of hate. (371-2)

At this point in the novel, Amy’s version of their story seems the more plausible by far. Nick is confessing to mischaracterizing her change, taking some responsibility for it. Now, he seems to accept that he was the one who didn’t live up to the terms of their original agreement.

But Nick’s understanding of the narrative at this point isn’t as settled as his mea culpa implies. What becomes clear from all the mulling and vacillating is that arriving at a definitive account of who provoked whom, who changed first, or who is ultimately to blame is all but impossible. Was Amy increasingly difficult to please? Or did Nick run out of steam? Just a few pages prior to admitting he’d been the first to undergo a deal-breaking transformation, Nick was expressing his disgust at what his futile efforts to make Amy happy had reduced him to:

For two years I tried as my old wife slipped away, and I tried so hard—no anger, no arguments, the constant kowtowing, the capitulation, the sitcom-husband version of me: Yes, dear. Of course, sweetheart. The fucking energy leached from my body as my frantic-rabbit thoughts tried to figure out how to make her happy, and each action, each attempt, was met with a rolled eye or a sad little sigh. A you just don’t get it sigh.

By the time we left for Missouri, I was just pissed. I was ashamed of the memory of me—the scuttling, scraping, hunchbacked toadie of a man I’d turned into. So I wasn’t romantic; I wasn’t even nice. (366)

The couple’s move from New York to Nick’s hometown in Missouri to help his sister care for their ailing mother is another point of contention between them. Nick had been laid off from the magazine he’d worked for. Amy had lost her job writing personality quizzes for a women’s magazine, and she’d also lost most of the trust fund her parents had set up for her when those same parents came asking for a loan to help bail them out after some of their investments went bad. So the conditions of the job market and the economy toward the end of the aughts were cranking up the pressure on both Nick and Amy as they strived to maintain some sense of themselves as exceptional human beings. But this added burden fell on each of them equally, so it doesn’t give us much help figuring out who was the first to succumb to bitterness.

Nonetheless, throughout the first half of Gone Girl Flynn works to gradually intensify our suspicion of Nick, making us wonder if he could possibly have flown into a blind rage and killed his wife before somehow dissociating himself from the memory of the crime. He gives the impression, for instance, that he’s trying to keep his affair with Andie secret from us, his readers and confessors, until he’s forced to come clean. Amy at one point reveals she was frightened enough of him to attempt to buy a gun. Nick also appears to have made a bunch of high-cost purchases with credit cards he denies ever having signed up for. Amy even bought extra life insurance a month or so before her disappearance—perhaps in response to some mysterious prompting from her husband. And there’s something weird about Nick’s relationship with his misogynist father, whose death from Alzheimer’s he’s eagerly awaiting. The second half of Gone Girl could have gone on to explore Nick’s psychosis and chronicle his efforts at escaping detection and capture. In that case, Flynn herself would have been surrendering to the pull of convention. But where she ends up going with her novel makes for a story that’s much more original—and, perhaps paradoxically, much more reflective of our modern societal values.

In one sense, the verdict about which character is truly to blame for the breakdown of the marriage is arbitrary. Marriages come apart at the seams because one or both partners no longer feel like they can be themselves all the time —affixing blame is little more than a postmortem exercise in recriminatory self-exculpation. If Gone Girl had been written as a literary instead of a genre work, it probably would have focused on the difficulty and ultimate pointlessness of figuring out whose subjective experiences were closest to reality, since our subjectivity is all we have to go on and our messy lives simply don’t lend themselves to clean narratives. But Flynn instead furnishes her thriller with an unmistakable and fantastically impressive villain, one whose aims and impulses so perfectly caricature the nastiest of our own that we can’t help elevating her to the ranks of our most beloved anti-heroes like Walter White and Frank Underwood (making me a little disappointed that David Fincher is making a movie out of the book instead of a cable or Netflix series).

Amy, we learn early in the novel, is not simply Amy but rather Amazing Amy, the inspiration for a series of wildly popular children’s books written by her parents, both of whom are child psychologists. The books are in fact the source of the money in the trust fund they had set up for her, and it is the lackluster sales of recent editions in the series, along with the spendthrift lifestyle they’d grown accustomed to, that drives them to ask for most of that money back. In the early chapters, Amy writes about how Amazing Amy often serves as a subtle rebuke from her parents, making good decisions in place of her bad ones, doing perfectly what she does ineptly. But later on we find out that the real Amy has nothing but contempt for her parents’ notions of what might constitute the ideal daughter. Far from worrying that she may not be living up to the standard set by her fictional counterpart, Amy feels the title of Amazing is part of her natural due. Indeed, when she first discovers Nick is cheating with Andie—a discovery she makes even before they sleep together the first time—what makes her the angriest about it is how mediocre it makes her seem. “I had a new persona,” she says, “not of my choosing. I was Average Dumb Woman Married to Average Shitty Man. He had single-handedly de-amazed Amazing Amy” (401).

Normally, Amy does choose which persona she wants to take on; that is in fact the crucial power that makes her worthy of her superhero sobriquet. Most of us no longer want to read stories about women who become the tragic victims of their complicatedly sympathetic but monstrously damaged husbands. With Amy, Flynn turns that convention inside-out. While real life seldom offers even remotely satisfying resolutions to the rival PR campaigns at the heart of so many dissolving marriages, Amy confesses—or rather boasts—to us, her readers and fans, that she was the one who had been acting like someone else at the beginning of the relationship.

Nick loved me. A six-O kind of love: He looooooved me. But he didn’t love me, me. Nick loved a girl who doesn’t exist. I was pretending, the way I often did, pretending to have a personality. I can’t help it, it’s what I’ve always done: The way some women change fashion regularly, I change personalities. What persona feels good, what’s coveted, what’s au courant? I think most people do this, they just don’t admit it, or else they settle on one persona because they’re too lazy or stupid to pull off a switch. (382)

This ability of Amy’s to take on whatever role she deems suitable for her at the moment is complemented by her adeptness at using people’s—her victims’—stereotype-based expectations of women against them. Taken together with her capacity for harboring long-term grudges in response to even the most seemingly insignificant of slights, these powers make Amazing Amy a heroic paragon of postmodern feminism. The catch is that to pull off her grand deception of Nick, the police, and the nattering public, she has to be a complete psychopath.

Amy assumes the first of the personas we encounter, Diary Amy, through writing, and the story she tells, equal parts fiction and lying, takes us in so effectively because it reprises some of our culture’s most common themes. Beyond the diary, the overarching story of Gone Girl so perfectly subverts the conventional abuse narrative that it’s hard not to admire Amy for refusing to be a character in it. Even after she’s confessed to framing Nick for her murder, the culmination of a plan so deviously vindictive her insanity is beyond question, it’s hard not to root for her when she pits herself against Desi, a former classmate she dated while attending a posh prep school called Wickshire Academy. Desi serves as the ideal anti-villain for our amazing anti-heroine. Amy writes,

It’s good to have at least one man you can use for anything. Desi is a white-knight type. He loves troubled women. Over the years, after Wickshire, when we’d talk, I’d ask after his latest girlfriend, and no matter the girl, he would always say: “Oh, she’s not doing very well, unfortunately.” But I know it is fortunate for Desi—the eating disorders, the painkiller addictions, the crippling depressions. He’s never happier than when he’s at a bedside. Not in bed, just perched nearby with broth and juice and a gently starched voice. Poor darling. (551-2)

Though an eagerness to save troubled women may not seem so damning at first blush, we soon learn that Desi’s ministrations are motived more by the expectation of gratitude and the relinquishing of control than by any genuine proclivity toward altruism. After Amy shows up claiming she’s hiding from Nick, she quickly becomes a prisoner in Desi’s house. And the way he treats her, so solicitous, so patronizing, so creepy—you almost can’t wait for Amy to decide he’s outlived his usefulness.

The struggle between Nick and Amy takes place against the backdrop of a society obsessed with celebrity and scandal. One of the things Nick is forced to learn, not to compete with Amy—which he’d never be able to do—but to merely survive, is to make himself sympathetic to people whose only contact with him is through the media. What Flynn conveys in depicting his efforts is the absurdity of trial by media. A daytime talk show host named Ellen Abbott—an obvious sendup of Nancy Grace—stirs her audience into a rage against Nick because he makes the mistake of forcing a smile in front of a camera. One of the effects of our media obsession is that we ceaselessly compare ourselves with characters in movies and TV. Nick finds himself at multiple points enacting scenes from cop shows, trying to act the familiar role of the innocent suspect. But he knows all the while that the story everyone is most familiar with, whether from fictional shows or those billed as nonfiction, is of the husband who tries to get away with murdering his wife.

Being awash in stories featuring celebrities and, increasingly, real people who are supposed to be just like us wouldn’t have such a virulent impact if we weren’t driven to compete with all of them. But, whenever someone says you don’t want to be that guy, what they’re really saying is that you should be better than that guy. Most of the toggling between identities Amy does is for the purpose of outshining any would-be rivals. In one oddly revealing passage, she even claims that focusing on outcompeting other couples made her happier than trying to win her individual struggle against Nick:

I thought we would be the most perfect union: the happiest couple around. Not that love is a competition. But I don’t understand the point of being together if you’re not the happiest.

I was probably happier for those few years—pretending to be someone else—than I ever have been before or after. I can’t decide what that means. (386-7)

The problem was that neither could maintain this focus on being the happiest couple because each found themselves competing against the other. It’s all well and good to look at how well your relationship works—how happy you both are in it—until some women you know start suggesting their husbands are more obedient than yours.

The challenge that was unique to Amy—that wasn’t really at all unique to Amy—entailed transitioning from the persona she donned to attract Nick and persuade him to marry her to a persona that would allow her to be comfortably dominant in the marriage. The persona women use to first land their man Amy refers to as the Cool Girl.

Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow still maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl. (383)

Amy is convinced Andie too is only pretending to be Cool Girl—because the Cool Girl can’t possibly exist. And the ire she directs at Nick arises out of her disappointment that he could believe the role she’d taken on was genuine.

I hated Nick for being surprised when I became me. I hated him for not knowing it had to end, for truly believing he had married this creature, this figment of the imagination of a million masturbatory men, semen-fingered and self-satisfied. (387)

Her reason for being contemptuous of women who keep trying to be the Cool Girl, the same reason she can’t bring herself to continue playing the role, is even more revealing. “If you let a man cancel plans or decline to do things for you,” she insists, “you lose.” She goes on to explain,

You don’t get what you want. It’s pretty clear. Sure, he may be happy, he may say you’re the coolest girl ever, but he’s saying it because he got his way. He’s calling you a Cool Girl to fool you! That’s what men do: They try to make it sound like you are the Cool Girl so you will bow to their wishes. Like a car salesman saying, How much do you want to pay for this beauty? when you didn’t agree to buy it yet. That awful phrase men use: “I mean, I know you wouldn’t mind if I…” Yes, I do mind. Just say it. Don’t lose, you dumb little twat. (387-8)

So Amy doesn’t want to be the one who loses any more than Nick wants to be that “sitcom-husband version” of himself, the toadie, the blunderer. And all either of them manages to accomplish by resisting is to make the other miserable.

Gen-Xers like Nick and Amy were taught to dream big, to grow up and change the world, to put their minds to it and become whatever they most want to be. Then they grew up and realized they had to find a way to live with each other and make some sort of living—even though whatever spouse, whatever job, whatever life they settled for inevitably became a symbol of the great cosmic joke that had been played on them. From thinking you’d be a hero and change the world to being cheated on by the husband who should have known he wasn’t good enough for you in first place—it’s quite a distance to fall. And it’s easy to imagine how much more you could accomplish without the dead weight of a broken heart or the burden of a guilty conscience. All you have driving you on is your rage, even the worst of which flares up only for a few days or weeks at most before exhausting itself. Then you return to being the sad, wounded, abandoned, betrayed little critter you are. Not Amy, though. Amy was the butt of the same joke as the rest of us, though in her case it was even more sadistic. She was made to settle for a lesser life than she’d been encouraged to dream of just like the rest of us. She was betrayed just like the rest of us. But she suffers no pangs of guilt, no aching of a broken heart. And Amy’s rage is inexhaustible. She really can be whoever she wants—and she’s already busy becoming more than an amazing idea.

And:

Science’s Difference Problem: Nicholas Wade’s Troublesome Inheritance and the Missing Moral Framework for Discussing the Biology of Behavior

Nicholas Wade went there. In his book “A Troublesome Inheritance,” he argues that not only is race a real, biological phenomenon, but one that has potentially important implications for our understanding of the fates of different peoples. Is it possible to even discuss such things without being justifiably labeled a racist? More importantly, if biological differences do show up in the research, how can we discuss them without being grossly immoral?

No sooner had Nicholas Wade’s new book become available for free two-day shipping than a contest began to see who could pen the most devastating critical review of it, the one that best satisfies our desperate urge to dismiss Wade’s arguments and reinforce our faith in the futility of studying biological differences between human races, a faith backed up by a cherished official consensus ever so conveniently in line with our moral convictions. That Charles Murray, one of the authors of the evil tome The Bell Curve, wrote an early highly favorable review for the Wall Street Journal only upped the stakes for all would-be champions of liberal science. Even as the victor awaits crowning, many scholars are posting links to their favorite contender’s critiques all over social media to advertise their principled rejection of this book they either haven’t read yet or have no intention of ever reading.

You don’t have to go beyond the title, A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History, to understand what all these conscientious intellectuals are so eager to distance themselves from—and so eager to condemn. History has undeniably treated some races much more poorly than others, so if their fates are in any small way influenced by genes the implication of inferiority is unavoidable. Regardless of what he actually says in the book, Wade’s very program strikes many as racist from its inception.

The going theories for the dawn of the European Enlightenment and the rise of Western culture—and western people—to global ascendency attribute the phenomenon to a combination of geographic advantages and historical happenstance. Wade, along with many other scholars, finds such explanations unsatisfying. Geography can explain why some societies never reached sufficient population densities to make the transition into states. “Much harder to understand,” Wade writes, “is how Europe and Asia, lying on much the same lines of latitude, were driven in the different directions that led to the West’s dominance” (223). Wade’s theory incorporates elements of geography—like the relatively uniform expanse of undivided territory between the Yangtze and Yellow rivers that facilitated the establishment of autocratic rule, and the diversity of fragmented regions in Europe preventing such consolidation—but he goes on to suggest that these different environments would have led to the development of different types of institutions. Individuals more disposed toward behaviors favored by these institutions, Wade speculates, would be rewarded with greater wealth, which would in turn allow them to have more children with behavioral dispositions similar to their own.

After hundreds of years and multiple generations, Wade argues, the populations of diverse regions would respond to these diverse institutions by evolving subtly different temperaments. In China for instance, favorable, and hence selected for traits may have included intelligence, conformity, and obedience. These behavioral propensities would subsequently play a role in determining the future direction of the institutions that fostered their evolution. Average differences in personality would, according to Wade, also make it more or less likely that certain new types of institution would arise within a given society, or that they could be successfully transplanted into it. And it’s a society’s institutions that ultimately determine its fate relative to other societies. To the objection that geography can, at least in principle, explain the vastly different historical outcomes among peoples of specific regions, Wade responds, “Geographic determinism, however, is as absurd a position as genetic determinism, given that evolution is about the interaction between the two” (222).

East Asians score higher on average on IQ tests than people with European ancestry, but there’s no evidence that any advantage they enjoy in intelligence, or any proclivity they may display toward obedience and conformity—traits supposedly manifest in their long history of autocratic governance—is attributable to genetic differences as opposed to traditional attitudes toward schoolwork, authority, and group membership inculcated through common socialization practices. So we can rest assured that Wade’s just-so story about evolved differences between the races in social behavior is eminently dismissible. Wade himself at several points throughout A Troublesome Inheritance admits that his case is wholly speculative. So why, given the abominable history of racist abuses of evolutionary science, would Wade publish such a book?

It’s not because he’s unaware of the past abuses. Indeed, in his second chapter, titled “Perversions of Science,” which none of the critical reviewers deigns to mention, Wade chronicles the rise of eugenics and its culmination in the Holocaust. He concludes,

After the Second World War, scientists resolved for the best of reasons that genetics research would never again be allowed to fuel the racial fantasies of murderous despots. Now that new information about human races has been developed, the lessons of the past should not be forgotten and indeed are all the more relevant. (38)

The convention among Wade’s critics is to divide his book into two parts, acknowledge that the first is accurate and compelling enough, and then unload the full academic arsenal of both scientific and moral objections to the second. This approach necessarily scants a few important links in his chain of reasoning in an effort to reduce his overall point to its most objectionable elements. And for all their moralizing, the critics, almost to a one, fail to consider Wade’s expressed motivation for taking on such a fraught issue.

Even acknowledging Wade’s case is weak for the role of biological evolution in historical developments like the Industrial Revolution, we may still examine his reasoning up to that point in the book, which may strike many as more firmly grounded. You can also start to get a sense of what was motivating Wade when you realize that the first half of A Troublesome Inheritance recapitulates his two previous books on human evolution. The first, Before the Dawn, chronicled the evolution and history of our ancestors from a species that resembled a chimpanzee through millennia as tribal hunter-gatherers to the first permanent settlements and the emergence of agriculture. Thus, we see that all along his scholarly interest has been focused on major transitions in human prehistory.

While critics of Wade’s latest book focus almost exclusively on his attempts at connecting genomics to geopolitical history, he begins his exploration of differences between human populations by emphasizing the critical differences between humans and chimpanzees, which we can all agree came about through biological evolution. Citing a number of studies comparing human infants to chimps, Wade writes in A Troublesome Inheritance,

Besides shared intentions, another striking social behavior is that of following norms, or rules generally agreed on within the “we” group. Allied with the rule following are two other basic principles of human social behavior. One is a tendency to criticize, and if necessary punish, those who do not follow the agreed-upon norms. Another is to bolster one’s own reputation, presenting oneself as an unselfish and valuable follower of the group’s norms, an exercise that may involve finding fault with others. (49)

What separates us from chimpanzees and other apes—including our ancestors—is our much greater sociality and our much greater capacity for cooperation. (Though primatologist Frans de Waal would object to leaving the much more altruistic bonobos out of the story.) The basis for these changes was the evolution of a suite of social emotions—emotions that predispose us toward certain types of social behaviors, like punishing those who fail to adhere to group norms (keeping mum about genes and race for instance). If there’s any doubt that the human readiness to punish wrongdoers and rule violators is instinctual, ongoing studies demonstrating this trait in children too young to speak make the claim that the behavior must be taught ever more untenable. The conclusion most psychologists derive from such studies is that, for all their myriad manifestations in various contexts and diverse cultures, the social emotions of humans emerge from a biological substrate common to us all.

After Before the Dawn, Wade came out with The Faith Instinct, which explores theories developed by biologist David Sloan Wilson and evolutionary psychologist Jesse Bering about the adaptive role of religion in human societies. In light of cooperation’s status as one of the most essential behavioral differences between humans and chimps, other behaviors that facilitate or regulate coordinated activity suggest themselves as candidates for having pushed our ancestors along the path toward several key transitions. Language for instance must have been an important development. Religion may have been another. As Wade argues in A Troublesome Inheritance,

The fact that every known society has a religion suggests that each inherited a propensity for religion from the ancestral human population. The alternative explanation, that each society independently invented and maintained this distinctive human behavior, seems less likely. The propensity for religion seems instinctual, rather than purely cultural, because it is so deeply set in the human mind, touching emotional centers and appearing with such spontaneity. There is a strong evolutionary reason, moreover, that explains why religion may have become wired in the neural circuitry. A major function of religion is to provide social cohesion, a matter of particular importance among early societies. If the more cohesive societies regularly prevailed over the less cohesive, as would be likely in any military dispute, an instinct for religious behavior would have been strongly favored by natural selection. This would explain why the religious instinct is universal. But the particular form that religion takes in each society depends on culture, just as with language. (125-6)

As is evident in this passage, Wade never suggests any one-to-one correspondence between genes and behaviors. Genes function in the context of other genes in the context of individual bodies in the context of several other individual bodies. But natural selection is only about outcomes with regard to survival and reproduction. The evolution of social behavior must thus be understood as taking place through the competition, not just of individuals, but also of institutions we normally think of as purely cultural.

The evolutionary sequence Wade envisions begins with increasing sociability enforced by a tendency to punish individuals who fail to cooperate, and moves on to tribal religions which involve synchronized behaviors, unifying beliefs, and omnipresent but invisible witnesses who discourage would-be rule violators. Once humans began living in more cohesive groups, behaviors that influenced the overall functioning of those groups became the targets of selection. Religion may have been among the first institutions that emerged to foster cohesion, but others relying on the same substrate of instincts and emotions would follow. Tracing the trajectory of our prehistory from the origin of our species in Africa, to the peopling of the world’s continents, to the first permanent settlements and the adoption of agriculture, Wade writes,

The common theme of all these developments is that when circumstances change, when a new resource can be exploited or a new enemy appears on the border, a society will change its institutions in response. Thus it’s easy to see the dynamics of how human social change takes place and why such a variety of human social structures exists. As soon as the mode of subsistence changes, a society will develop new institutions to exploit its environment more effectively. The individuals whose social behavior is better attuned to such institutions will prosper and leave more children, and the genetic variations that underlie such a behavior will become more common. (63-4)

First a society responds to shifting pressures culturally, but a new culture amounts to a new environment for individuals to adapt to. Wade understands that much of this adaptation occurs through learning. Some of the challenges posed by an evolving culture will, however, be easier for some individuals to address than others. Evolutionary anthropologists tend to think of culture as a buffer between environments and genes. Many consider it more of a wall. To Wade, though, culture is merely another aspect of the environment individuals and their genes compete to thrive in.

If you’re a cultural anthropologist and you want to study how cultures change over time, the most convenient assumption you can make is that any behavioral differences you observe between societies or over periods of time are owing solely to the forces you’re hoping to isolate. Biological changes would complicate your analysis. If, on the other hand, you’re interested in studying the biological evolution of social behaviors, you will likely be inclined to assume that differences between cultures, if not based completely on genetic variance, at least rest on a substrate of inherited traits. Wade has quite obviously been interested in social evolution since his first book on anthropology, so it’s understandable that he would be excited about genome studies suggesting that human evolution has been operating recently enough to affect humans in distantly separated regions of the globe. And it’s understandable that he’d be frustrated by sanctions against investigating possible behavioral differences tied to these regional genetic differences. But this doesn’t stop his critics from insinuating that his true agenda is something other than solely scientific.

On the technology and pop culture website io9, blogger and former policy analyst Annalee Newitz calls Wade’s book an “argument for white supremacy,” which goes a half-step farther than the critical review by Eric Johnson the post links to, titled "On the Origin of White Power." Johnson sarcastically states that Wade isn’t a racist and acknowledges that the author is correct in pointing out that considering race as a possible explanatory factor isn’t necessarily racist. But, according to Johnson’s characterization,

He then explains why white people are better because of their genes. In fairness, Wade does not say Caucasians are betterper se, merely better adapted (because of their genes) to the modern economic institutions that Western society has created, and which now dominate the world’s economy and culture.

The clear implication here is that Wade’s mission is to prove that the white race is superior but that he also wanted to cloak this agenda in the garb of honest scientific inquiry. Why else would Wade publish his problematic musings? Johnson believes that scientists and journalists should self-censor speculations or as-yet unproven theories that could exacerbate societal injustices. He writes, “False scientific conclusions, often those that justify certain well-entrenched beliefs, can impact peoples’ lives for decades to come, especially when policy decisions are based on their findings.” The question this position begs is how certain can we be that any scientific “conclusion”—Wade would likely characterize it as an exploration—is indeed false before it’s been made public and become the topic of further discussion and research?

Johnson’s is the leading contender for the title of most devastating critique of A Troublesome Inheritance, and he makes several excellent points that severely undermine parts of Wade’s case for natural selection playing a critical role in recent historical developments. But, like H. Allen Orr’s critique in The New York Review, the first runner-up in the contest, Johnson’s essay is oozing with condescension and startlingly unselfconscious sanctimony. These reviewers profess to be standing up for science even as they ply their readers with egregious ad hominem rhetoric (Wade is just a science writer, not a scientist) and arguments from adverse consequences (racist groups are citing Wade’s book in support of their agendas), thereby underscoring another of Wade’s arguments—that the case against racial differences in social behavior is at least as ideological as it is scientific. Might the principle that researchers should go public with politically sensitive ideas or findings only after they’ve reached some threshold of wider acceptance end up stifling free inquiry? And, if Wade’s theories really are as unlikely to bear empirical or conceptual fruit as his critics insist, shouldn’t the scientific case against them be enough? Isn’t all the innuendo and moral condemnation superfluous—maybe even a little suspicious?

White supremacists may get some comfort from parts of Wade’s book, but if they read from cover to cover they’ll come across plenty of passages to get upset about. In addition to the suggestion that Asians are more intelligent than Caucasians, there’s the matter of the entire eighth chapter, which describes a scenario for how Ashkenazi Jews became even more intelligent than Asians and even more creative and better suited to urban institutions than Caucasians of Northern European ancestry. Wade also points out more than once that the genetic differences between the races are based, not on the presence or absence of single genes, but on clusters of alleles occurring with varying frequencies. He insists that

the significant differences are those between societies, not their individual members. But minor variations in social behavior, though barely perceptible, if at all, in an individual, combine to create societies of very different character. (244)

In other words, none of Wade’s speculations, nor any of the findings he reports, justifies discriminating against any individual because of his or her race. At best, there would only ever be a slightly larger probability that an individual will manifest any trait associated with people of the same ancestry. You’re still much better off reading the details of the résumé. Critics may dismiss as mere lip service Wade’s disclaimers about how “Racism and discrimination are wrong as a matter of principle, not of science” (7), and how the possibility of genetic advantages in certain traits “does not of course mean that Europeans are superior to others—a meaningless term in any case from an evolutionary perspective” (238). But if Wade is secretly taking delight in the success of one race over another, it’s odd how casually he observes that “the forces of differentiation seem now to have reversed course due to increased migration, travel and intermarriage” (71).

Wade does of course have to cite some evidence, indirect though it may be, in support of his speculations. First, he covers several genomic studies showing that, contrary to much earlier scholarship, populations of various regions of the globe are genetically distinguishable. Race, in other words, is not merely a social construct, as many have insisted. He then moves on to research suggesting that a significant portion of the human genome reveals evidence of positive selection recently enough to have affected regional populations differently. Joshua Akey’s 2009 review of multiple studies on markers of recent evolution is central to his argument. Wade interprets Akey’s report as suggesting that as much as 14 percent of the human genome shows signs of recent selection. Orr insists this is a mistake in his review, putting the number at 8 percent.

Steven Pinker, who discusses Akey’s paper in his 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, likewise takes the number to be 8 and not 14. But even that lower proportion is significant. Pinker, an evolutionary psychologist, stresses just how revolutionary this finding might be.

Some journalists have uncomprehendingly lauded these results as a refutation of evolutionary psychology and what they see as its politically dangerous implication of a human nature shaped by adaptation to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In fact the evidence for recent selection, if it applies to genes with effects on cognition and emotion, would license a far more radical form of evolutionary psychology, one in which minds have been biologically shaped by recent environments in addition to ancient ones. And it could have the incendiary implication that aboriginal and immigrant populations are less biologically adapted to the demands of modern life than populations that have lived in literate societies for millennia. (614)

Contra critics who paint him as a crypto-supremacist, it’s quite clearly that “far more radical form of evolutionary psychology” Wade is excited about. That’s why he’s exasperated by what he sees as Pinker’s refusal to admit that the case for that form is strong enough to warrant pursuing it further owing to fear of its political ramifications. Pinker does consider much of the same evidence as Wade, but where Wade sees only clear support Pinker sees several intractable complications. Indeed, the section of Better Angels where Pinker discusses recent evolution is an important addendum to Wade’s book, and it must be noted Pinker doesn’t rule out the possibility of regional selection for social behaviors. He simply says that “for the time being, we have no need for that hypothesis” (622).

Wade is also able to point to one gene that has already been identified whose alleles correspond to varying frequencies of violent behavior. The MAO-A gene comes in high- and low-activity varieties, and the low-activity version is more common among certain ethnic groups, like sub-Saharan Africans and Maoris. But, as Pinker points out, a majority of Chinese men also have the low-activity version of the gene, and they aren’t known for being particularly prone to violence. So the picture isn’t straightforward. Aside from the Ashkenazim, Wade cites another well-documented case in which selection for behavioral traits could have played an important role. In his book A Farewell to Alms, Gregory Clark presents an impressive collection of historical data suggesting that in the lead-up to the Industrial Revolution in England, people with personality traits that would likely have contributed to the rapid change were rewarded with more money, and people with more money had more children. The children of the wealthy would quickly overpopulate the ranks of the upper classes and thus large numbers of them inevitably descended into lower ranks. The effect of this “ratchet of wealth” (180), as Wade calls it, after multiple generations would be genes for behaviors like impulse control, patience, and thrift cascading throughout the population, priming it for the emergence of historically unprecedented institutions.

Wade acknowledges that Clark’s theory awaits direct confirmation through the discovery of actual alleles associated with the behavioral traits he describes. But he points to experiments with artificial selection that suggest the time-scale Clark considers, about 24 generations, would have been sufficient to effect measurable changes. In his critical review, though, Johnson counters that natural selection is much slower than artificial selection, and he shows that Clark’s own numbers demonstrate a rapid attenuation of the effects of selection. Pinker points to other shortcomings in the argument, like the number of cases in which institutions changed and populations exploded in periods too short to have seen any significant change in allele frequencies. Wade isn’t swayed by any of these objections, which he takes on one-by-one, contrary to Orr’s characterization of the disagreement. As of now, the debate is ongoing. It may not be settled conclusively until scientists have a much better understanding of how genes work to influence behavior, which Wade estimates could take decades.

Pinker is not known for being politically correct, but Wade may have a point when he accuses him of not following the evidence to the most likely conclusions. “The fact that a hypothesis is politically uncomfortable,” Pinker writes, “does not mean that it is false, but it does mean that we should consider the evidence very carefully before concluding that it is true” (614). This sentiment echoes the position taken by Johnson: Hold off going public with sensitive ideas until you’re sure they’re right. But how can we ever be sure whether an idea has any validity if we’re not willing to investigate it? Wade’s case for natural selection operating through changing institutions during recorded history isn’t entirely convincing, but neither is it completely implausible. The evidence that would settle the issue simply hasn’t been discovered yet. But neither is there any evidence in Wade’s book to support the conclusion that his interest in the topic is political as opposed to purely scientific. “Each gene under selection,” he writes, “will eventually tell a fascinating story about some historical stress to which the population was exposed and then adapted” (105). Fascinating indeed, however troubling they may be.

Is the best way to handle troublesome issues like the possible role of genes in behavioral variations between races to declare them off-limits to scientists until the evidence is incontrovertible? Might this policy come with the risk that avoiding the topic now will make it all too easy to deny any evidence that does emerge later? If genes really do play a role in violence and impulse-control, then we may need to take that into account when we’re devising solutions to societal inequities.

Genes are not gods whose desires must be bowed to. But neither are they imaginary forces that will go away if we just ignore them. The challenge of dealing with possible biological differences also arises in the context of gender. Because women continue to earn smaller incomes on average than men and are underrepresented in science and technology fields, and because the discrepancy is thought to be the product of discrimination and sexism, many scholars argue that any research into biological factors that may explain these outcomes is merely an effort at rationalizing injustice. The problem is the evidence for biological differences in behavior between the genders is much stronger than it is for those between populations from various regions. We can ignore these findings—and perhaps even condemn the scientists who conduct the studies—because they don’t jive with our preferred explanations. But solutions based on willful ignorance have little chance of being effective.

The sad fact is that scientists and academics have nothing even resembling a viable moral framework for discussing biological behavioral differences. Their only recourse is to deny and inveigh. The quite reasonable fear is that warnings like Wade’s about how the variations are subtle and may not exist at all in any given individual will go unheeded as the news of the findings is disseminated, and dumbed-down versions of the theories will be coopted in the service of reactionary agendas. A study reveals that women respond more readily to a baby’s vocalizations and the headlines read “Genes Make Women Better Parents.” An allele associated with violent behavior is found to be more common in African Americans and some politician cites it as evidence that the astronomical incarceration rate for black males is justifiable. But is censorship the answer? Average differences between genders in career preferences is directly relevant to any discussion of uneven representation in various fields. And it’s possible that people with a certain allele will respond differently to different types of behavioral intervention. As Carl Sagan explained, in a much different context, in his book Demon-Haunted World, “we cannot have science in bits and pieces, applying it where we feel safe and ignoring it where we feel threatened—again, because we are not wise enough to do so” (297).

Part of the reason the public has trouble understanding what differences between varying types of people may mean is that scientists are at odds with each other about how to talk about them. And with all the righteous declamations they can start to sound a lot like the talking heads on cable news shows. Conscientious and well-intentioned scholars have so thoroughly poisoned the well when it comes to biological behavioral differences that their possible existence is treated as a moral catastrophe. How should we discuss the topic? Working to convey the importance of the distinction between average and absolute differences may be a good start. Efforts to encourage people to celebrate diversity and to challenge the equating of genes with destiny are already popularly embraced. In the realm of policy, we might shift our focus from equality of outcome to equality of opportunity. It’s all too easy to find clear examples of racial disadvantages—in housing, in schooling, in the job market—that go well beyond simple head counting at top schools and in executive boardrooms. Slight differences in behavioral propensities can’t justify such blatant instances of unfairness. Granted, that type of unfairness is much more difficult to find when it comes to gender disparities, but the lesson there is that policies and agendas based on old assumptions might need to give way to a new understanding, not that we should pretend the evidence doesn’t exist or has no meaning.

Wade believes it was safe for him to write about race because “opposition to racism is now well entrenched” in the Western world (7). In one sense, he’s right about that. Very few people openly profess a belief in racial hierarchies. In another sense, though, it’s just as accurate to say that racism is itself well entrenched in our society. Will A Troublesome Inheritance put the brakes on efforts to bring about greater social justice? This seems unlikely if only because the publication of every Bell Curve occasions the writing of another Mismeasure of Man.

The unfortunate result is that where you stand on the issue will become yet another badge of political identity as we form ranks on either side. Most academics will continue to consider speculation irresponsible, apply a far higher degree of scrutiny to the research, and direct the purest moral outrage they can muster, while still appearing rational and sane, at anyone who dares violate the taboo. This represents the triumph of politics over science. And it ensures the further entrenchment of views on either side of the divide.

Despite the few superficial similarities between Wade’s arguments and those of racists and eugenicists of centuries past, we have to realize that our moral condemnation of what we suppose are his invidious extra-scientific intentions is itself borne of extra-scientific ideology. Whether race plays a role in behavior is a scientific question. Our attitude toward that question and the parts of the answer that trickle in despite our best efforts at maintaining its status as taboo just may emerge out of assumptions that no longer apply. So we must recognize that succumbing to the temptation to moralize when faced with scientific disagreement automatically makes hypocrites of us all. And we should bear in mind as well that insofar as racial and gender differences really do exist it will only be through coming to a better understanding of them that we can hope to usher in a more just society for children of any and all genders and races.

Also read:

And:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

And:

FROM DARWIN TO DR. SEUSS: DOUBLING DOWN ON THE DUMBEST APPROACH TO COMBATTING RACISM

Are 1 in 5 Women Really Sexually Assaulted on College Campuses?

If you wanted to know how many young women are sexually assaulted on college campuses, you could easily devise a survey to ask a sample of them directly. But that’s not what advocates of stricter measures to prevent assault tend to do. Instead, they ask ambiguous questions they go on to interpret as suggesting an assault occurred. This almost guarantees wildly inflated numbers.

If you were a university administrator and you wanted to know how prevalent a particular experience was for students on campus, you would probably conduct a survey that asked a few direct questions about that experience—foremost among them the question of whether the student had at some point had the experience you’re interested in. Obvious, right? Recently, we’ve been hearing from many news media sources, and even from President Obama himself, that one in five college women experience sexual assault at some time during their tenure as students. It would be reasonable to assume that the surveys used to arrive at this ratio actually asked the participants directly whether or not they had been assaulted.

But it turns out the web survey that produced the one-in-five figure did no such thing. Instead, it asked students whether they had had any of several categories of experience the study authors later classified as sexual assault, or attempted sexual assault, in their analysis. This raises the important question of how we should define sexual assault when we’re discussing the issue—along with the related question of why we’re not talking about a crime that’s more clearly defined, like rape.

Of course, whatever you call it, sexual violence is such a horrible crime that most of us are willing to forgive anyone who exaggerates the numbers or paints an overly frightening picture of reality in an attempt to prevent future cases. (The issue is so serious that PolitiFact refrained from applying their trademark Truth-O-Meter to the one-in-five figure.)

But there are four problems with this attitude. The first is that for every supposed assault there is an alleged perpetrator. Dramatically overestimating the prevalence of the crime comes with the attendant risk of turning public perception against the accused, making it more difficult for the innocent to convince anyone of their innocence.