READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

How to be Interesting: Dead Poets and Causal Inferences

Henry James famously wrote, “The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting.” But how does one be interesting? The answer probably lies in staying one step ahead of your readers, but every reader moves at their own pace.

No one writes a novel without ever having read one. Though storytelling comes naturally to us as humans, our appreciation of the lengthy, intricately rendered narratives we find spanning the hundreds of pages between book covers is contingent on a long history of crucial developments, literacy for instance. In the case of an individual reader, the faithfulness with which ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny will largely determine the level of interest taken in any given work of fiction. In other words, to appreciate a work, it is necessary to have some knowledge of the literary tradition to which it belongs. T.S. Eliot’s famous 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” eulogizes great writers as breathing embodiments of the entire history of their art. “The poet must be very conscious of the main current,” Eliot writes,

which does not at all flow invariably through the most distinguished reputations. He must be quite aware of the obvious fact that art never improves, but that the material of art is never quite the same. He must be aware that the mind of Europe—the mind of his own country—a mind which he learns in time to be much more important than his own private mind—is a mind which changes, and that this change is a development which abandons nothing en route, which does not superannuate either Shakespeare, or Homer, or the rock of the Magdalenian draughtsmen.

Though Eliot probably didn’t mean to suggest that to write a good poem or novel you have to have thoroughly mastered every word of world literature, a condition that would’ve excluded most efforts even at the time he wrote the essay, he did believe that to fully understand a work you have to be able to place it in its proper historical context. “No poet,” he wrote,

no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead.

If this formulation for what goes into the appreciation of art is valid, then as time passes and historical precedents accumulate the burden of knowledge that must be shouldered to sustain adequate interest in or appreciation for works in the tradition will be getting constantly bigger. Accordingly, the number of people who can manage it will be getting constantly smaller.

But what if there is something like a threshold awareness of literary tradition—or even of current literary convention—beyond which the past ceases to be the most important factor influencing your appreciation for a particular work? Once your reading comprehension is up to snuff and you’ve learned how to deal with some basic strategies of perspective—first person, third person omniscient, etc.—then you’re free to interpret stories not merely as representative of some tradition but of potentially real people and events, reflective of some theme that has real meaning in most people’s lives. Far from seeing the task of the poet or novelist as serving as a vessel for artistic tradition, Henry James suggests in his 1884 essay “The Art of Fiction” that

The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting. That general responsibility rests upon it, but it is the only one I can think of. The ways in which it is at liberty to accomplish this result (of interesting us) strike me as innumerable and such as can only suffer from being marked out, or fenced in, by prescription. They are as various as the temperament of man, and they are successful in proportion as they reveal a particular mind, different from others. A novel is in its broadest definition a personal impression of life; that, to begin with, constitutes its value, which is greater or less according to the intensity of the impression.

Writing for dead poets the way Eliot suggests may lead to works that are historically interesting. But a novel whose primary purpose is to represent, say, Homer’s Odyssey in some abstract way, a novel which, in other words, takes a piece of literature as its subject matter rather than some aspect of life as it is lived by humans, will likely only ever be interesting to academics. This isn’t to say that writers of the past ought to be ignored; rather, their continuing relevance is likely attributable to their works’ success in being interesting. So when you read Homer you shouldn’t be wondering how you might artistically reconceptualize his epics—you should be attending to the techniques that make them interesting and wondering how you might apply them in your own work, which strives to artistically represent some aspect of live. You go to past art for technical or thematic inspiration, not for traditions with which to carry on some dynamic exchange.

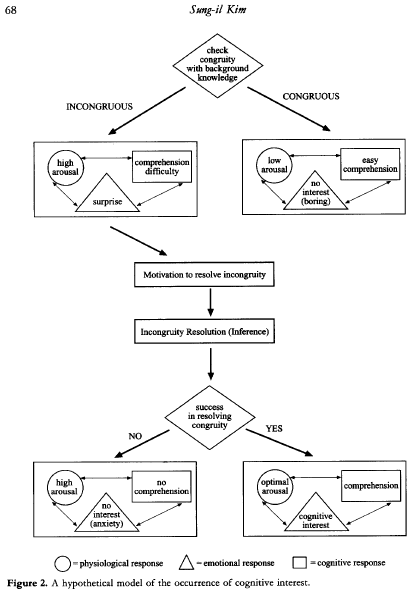

Representation should, as a rule of thumb, take priority over tradition. And to insist, as Eliot does, as an obvious fact or otherwise, that artistic techniques never improve is to admit defeat before taking on the challenge. But this leaves us with the question of how, beyond a devotion to faithful representations of recognizably living details, one manages to be interesting. Things tend to interest us when they’re novel or surprising. That babies direct their attention to incidents which go against their expectations is what allows us to examine what those expectations are. Babies, like their older counterparts, stare longer at bizarre occurrences. If a story consisted of nothing but surprising incidents, however, we would probably lose interest in it pretty quickly because it would strike us as chaotic and incoherent. Citing research showing that while surprise is necessary in securing the interest of readers but not sufficient, Sung-Il Kim, a psychologist at Korea University, explains that whatever incongruity causes the surprise must somehow be resolved. In other words, the surprise has to make sense in the shifted context.

In Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster makes his famous distinction between flat and round characters with reference to the latter’s ability to surprise readers. He notes however that surprise is only half the formula, since a character who only surprises would seem merely erratic—or would seem like something other than a real person. He writes,

The test of a round character is whether it is capable of surprising in a convincing way. If it never surprises, it is flat. If it does not convince, it is a flat pretending to be round. It has the incalculability of life about it—life within the pages of a book. And by using it sometimes alone, more often in combination with the other kind, the novelist achieves his task of acclimatization and harmonizes the human race with the other aspects of his work. (78)

Kim discovered that this same dynamic is at play even in the basic of unit of a single described event, suggesting that the convincing surprise is important for all aspects of the story, not just character. He went on to test the theory that what lies at the heart of our interest in these seeming incongruities that are in time resolved is our tendency to anticipate the resolution. When a brief description involves some element that must be inferred, it is considered more interesting, and it proves more memorable, than when the same incident is described in full detail without any demand for inference. However, when researchers rudely distract readers in experiments, keeping them from being able to infer, the differences in recall and reported interest vanish.

Kim proposes a “causal bridging inference” theory to explain what makes a story interesting. If there aren’t enough inferences to be made, the story seems boring and banal. But if there are too many then the reader gets overwhelmed and spaces out. “Whether inferences are drawn or not,” Kim writes,

depends on two factors: the amount of background knowledge a reader possesses and the structure of a story… In a real life situation, for example, people are interested in new scientific theories, new fashion styles, or new leading-edge products only when they have an adequate amount of background knowledge on the domain to fill the gap between the old and the new… When a story contains such detailed information that there is no gap to fill in, a reader does not need to generate inferences. In this case, the story would not be interesting even if the reader possessed a great deal of background knowledge. (69)

One old-fashioned and intuitive way of thinking about causal bridge inference theory is to see the task of a writer as keeping one or two steps ahead of the reader. If the story runs ahead by more than a few steps it risks being too difficult to follow and the reader gets lost. If it falls behind, it drags, like the boor who relishes the limelight and so stretches out his anecdotes with excruciatingly superfluous detail.

For a writer, the takeaway is that you want to shock and surprise your readers, which means making your story take unexpected, incongruous turns, but you should also seed the narrative with what in hindsight can be seen as hints to what’s to come so that the surprises never seem random or arbitrary—and so that the reader is trained to seek out further clues to make further inferences. This is what Forster meant when he said characters should change in ways that are both surprising and convincing. It’s perhaps a greater achievement to have character development, plot, and language integrated so that an inevitable surprise in one of these areas has implications for or bleeds into both the others. But we as readers can enjoy on its own an unlikely observation or surprising analogy that we discover upon reflection to be fitting. And of course we can enjoy a good plot twist in isolation too—witness Hollywood and genre fiction.

Naturally, some readers can be counted on to be better at making inferences than others. As Kim points out, this greater ability may be based on a broader knowledge base; if the author makes an allusion, for instance, it helps to know about the subject being alluded to. It can also be based on comprehension skills, awareness of genre conventions, understanding of the physical or psychological forces at play in the plot, and so on. The implication is that keeping those crucial two steps ahead, no more no less, means targeting readers who are just about as good at making inferences as you are and working hard through inspiration, planning, and revision to maintain your lead. If you’re erudite and agile of mind, you’re going to bore yourself trying to write for those significantly less so—and those significantly less so are going to find what is keenly stimulating for you to write all but impossible to comprehend.

Interestingness is also influenced by fundamental properties of stories like subject matter—Percy Fawcett explores the Amazon in search of the lost City of Z is more interesting than Margaret goes grocery shopping—and the personality traits of characters that influence the degree to which we sympathize with them. But technical virtuosity often supersedes things like topic and character. A great writer can write about a boring character in an interesting way. Interestingly, however, the benefit in interest won through mastery of technique will only be appreciated by those capable of inferring the meaning hinted at by the narration, those able to make the proper conceptual readjustments to accommodate surprising shifts in context and meaning. When mixed martial arts first became popular, for instance, audiences roared over knockouts and body slams, and yawned over everything else. But as Joe Rogan has remarked from ringside at events over the past few years fans have become so sophisticated that they cheer when one fighter passes the other’s guard.

What this means is that no matter how steadfast your devotion to representation, assuming your skills continually develop, there will be a point of diminishing returns, a point where improving as a writer will mean your work has greater interest but to a shrinking audience. My favorite illustration of this dilemma is Steven Millhauser’s parable “In the Reign of Harad IV,” in which “a maker of miniatures” carves and sculpts tiny representations of a king’s favorite possessions. Over time, though, the miniaturist ceases to care about any praise he receives from the king or anyone else at court and begins working to satisfy an inner “stirring of restlessness.” His creations become smaller and smaller, necessitating greater and greater magnification tools to appreciate. No matter how infinitesimal he manages to make his miniatures, upon completion of each work he seeks “a farther kingdom.” It’s one of the most interesting short stories I’ve read in a while.

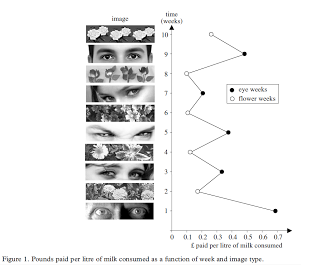

Causal Bridging Inference Model:

What's the Point of Difficult Reading?

For every John Galt, Tony Robbins, and Scheherazade, we may need at least half a Proust. We are still, however, left with quite a dilemma. Some authors really are just assholes who write worthless tomes designed to trick you into wasting your time. But some books that seem impenetrable on the first attempt will reward your efforts to decipher them.

You sit reading the first dozen or so pages of some celebrated classic and gradually realize that having to sort out how the ends of the long sentences fix to their beginnings is taking just enough effort to distract you entirely from the setting or character you’re supposed to be getting to know. After a handful of words you swear are made up and a few tangled metaphors you find yourself riddling over with nary a resolution, the dread sinks in. Is the whole book going to be like this? Is it going to be one of those deals where you get to what’s clearly meant to be a crucial turning point in the plot but for you is just another riddle without a solution, sending you paging back through the forest of verbiage in search of some key succession of paragraphs you spaced out while reading the first time through? Then you wonder if you’re missing some other kind of key, like maybe the story’s an allegory, a reference to some historical event like World War II or some Revolution you once had to learn about but have since lost all recollection of. Maybe the insoluble similes are allusions to some other work you haven’t read or can’t recall. In any case, you’re not getting anything out of this celebrated classic but frustration leading to the dual suspicion that you’re too ignorant or stupid to enjoy great literature and that the whole “great literature” thing is just a conspiracy to trick us into feeling dumb so we’ll defer to the pseudo-wisdom of Ivory Tower elites.

If enough people of sufficient status get together and agree to extol a work of fiction, they can get almost everyone else to agree. The readers who get nothing out of it but frustration and boredom assume that since their professors or some critic in a fancy-pants magazine or the judges of some literary award committee think it’s great they must simply be missing something. They dutifully continue reading it, parrot a few points from a review that sound clever, and afterward toe the line by agreeing that it is indeed a great work of literature, clearly, even if it doesn’t speak to them personally. For instance, James Joyce’s Ulysses, utterly nonsensical to anyone without at least a master’s degree, tops the Modern Library’s list of 100 best novels in the English language. Responding to the urging of his friends to write out an explanation of the novel, Joyce scoffed, boasting,

I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of ensuring one’s immortality.

He was right. To this day, professors continue to love him even as Ulysses and the even greater monstrosity Finnegan’s Wake do nothing but bore and befuddle everyone else—or else, more fittingly, sit inert or unchecked-out on the shelf, gathering well-deserved dust.

Joyce’s later novels are not literature; they are lengthy collections of loosely connected literary puzzles. But at least his puzzles have actual solutions—or so I’m told. Ulysses represents the apotheosis of the tradition in literature called modernism. What came next, postmodernism, is even more disconnected from the universal human passion for narrative. Even professors aren’t sure what to do with it, so they simply throw their hands up, say it’s great, and explain that the source of its greatness is its very resistance to explanation. Jonathan Franzen, whose 2001 novel The Corrections represented a major departure from the postmodernism he began his career experimenting with, explained the following year in The New Yorker how he’d turned away from the tradition. He’d been reading the work of William Gaddis “as a kind of penance” (101) and not getting any meaning out of it. Of the final piece in the celebrated author’s oeuvre, Franzen writes,

The novel is an example of the particular corrosiveness of literary postmodernism. Gaddis began his career with a Modernist epic about the forgery of masterpieces. He ended it with a pomo romp that superficially resembles a masterpiece but punishes the reader who tries to stay with it and follow its logic. When the reader finally says, Hey, wait a minute, this is a mess, not a masterpiece, the book instantly morphs into a performance-art prop: its fraudulence is the whole point! And the reader is out twenty hours of good-faith effort. (111)

In other words, reading postmodern fiction means not only forgoing the rewards of narratives, having them replaced by the more taxing endeavor of solving multiple riddles in succession, but those riddles don’t even have answers. What’s the point of reading this crap? Exactly. Get it?

You can dig deeper into the meaningless meanderings of pomos and discover there is in fact an ideology inspiring all the infuriating inanity. The super smart people who write and read this stuff point to the willing, eager complicity of the common reader in the propagation of all the lies that sustain our atrociously unjust society (but atrociously unjust compared to what?). Franzen refers to this as the Fallacy of the Stupid Reader,

wherein difficulty is a “strategy” to protect art from cooptation and the purpose of art is to “upset” or “compel” or “challenge” or “subvert” or “scar” the unsuspecting reader; as if the writer’s audience somehow consisted, again and again, of Charlie Browns running to kick Lucy’s football; as if it were a virtue in a novelist to be the kind of boor who propagandizes at friendly social gatherings. (109)

But if the author is worried about art becoming a commodity does making the art shitty really amount to a solution? And if the goal is to make readers rethink something they take for granted why not bring the matter up directly, or have a character wrestle with it, or have a character argue with another character about it? The sad fact is that these authors probably just suck, that, as Franzen suspects, “literary difficulty can operate as a smoke screen for an author who has nothing interesting, wise, or entertaining to say” (111).

Not all difficulty in fiction is a smoke screen though. Not all the literary emperors are naked. Franzen writes that “there is no headache like the headache you get from working harder on deciphering a text than the author, by all appearances, has worked on assembling it.” But the essay, titled “Mr. Difficult,” begins with a reader complaint sent not to Gaddis but to Franzen himself. And the reader, a Mrs. M. from Maryland, really gives him the business:

Who is it that you are writing for? It surely could not be the average person who enjoys a good read… The elite of New York, the elite who are beautiful, thin, anorexic, neurotic, sophisticated, don’t smoke, have abortions tri-yearly, are antiseptic, live in penthouses, this superior species of humanity who read Harper’s and The New Yorker. (100)

In this first part of the essay, Franzen introduces a dilemma that sets up his explanation of why he turned away from postmodernism—he’s an adherent of the “Contract model” of literature, whereby the author agrees to share, on equal footing, an entertaining or in some other way gratifying experience, as opposed to the “Status model,” whereby the author demonstrates his or her genius and if you don’t get it, tough. But his coming to a supposed agreement with Mrs. M. about writers like Gaddis doesn’t really resolve Mrs. M.’s conflict with him.

The Corrections, after all, the novel she was responding to, represents his turning away from the tradition Gaddis wrote in. (It must be said, though, that Freedom, Franzen’s next novel, is written in a still more accessible style.)

The first thing we must do to respond properly to Mrs. M. is break down each of Franzen’s models into two categories. The status model includes writers like Gaddis whose difficulty serves no purpose but to frustrate and alienate readers. But Franzen’s own type specimen for this model is Flaubert, much of whose writing, though difficult at first, rewards any effort to re-read and further comprehend with a more profound connection. So it is for countless other writers, the one behind number two on the Modern Library’s ranking for instance—Fitzgerald and Gatsby. As for the contract model, Franzen admits,

Taken to its free-market extreme, Contract stipulates that if a product is disagreeable to you the fault must be the product’s. If you crack a tooth on a hard word in a novel, you sue the author. If your professor puts Dreiser on your reading list, you write a harsh student evaluation… You’re the consumer; you rule. (100)

Franzen, in declaring himself a “Contract kind of person,” assumes that the free-market extreme can be dismissed for its extremity. But Mrs. M. would probably challenge him on that. For many, particularly right-leaning readers, the market not only can but should be relied on to determine which books are good and which ones belong in some tiny niche. When the Modern Library conducted a readers' poll to create a popular ranking to balance the one made by experts, the ballot was stuffed by Ayn Rand acolytes and scientologists. Mrs. M. herself leaves little doubt as to her political sympathies. For her and her fellow travelers, things like literature departments, National Book Awards—like the one The Corrections won—Nobels and Pulitzers are all an evil form of intervention into the sacred workings of the divine free market, un-American, sacrilegious, communist. According to this line of thinking, authors aren’t much different from whores—except of course literal whoring is condemned in the bible (except when it isn’t).

A contract with readers who score high on the personality dimension of openness to new ideas and experiences (who tend to be liberal), those who have spent a lot of time in the past reading books like The Great Gatsby or Heart of Darkness or Lolita (the horror!), those who read enough to have developed finely honed comprehension skills—that contract is going to look quite a bit different from one with readers who attend Beck University, those for whom Atlas Shrugged is the height of literary excellence. At the same time, though, the cult of self-esteem is poisoning schools and homes with the idea that suggesting that a student or son or daughter is anything other than a budding genius is a form of abuse. Heaven forbid a young person feel judged or criticized while speaking or writing. And if an author makes you feel the least bit dumb or ignorant, well, it’s an outrage—heroes like Mrs. M. to the rescue.

One of the problems with the cult of self-esteem is that anticipating criticism tends to make people more, not less creative. And the link between low self-esteem and mental disorders is almost purely mythical. High self-esteem is correlated with school performance, but as far as researchers can tell it’s the performance causing the esteem, not the other way around. More invidious, though, is the tendency to view anything that takes a great deal of education or intelligence to accomplish as an affront to everyone less educated or intelligent. Conservatives complain endlessly about class warfare and envy of the rich—the financially elite—but they have no qualms about decrying intellectual elites and condemning them for flaunting their superior literary achievements. They see the elitist mote in the eye of Nobel laureates without noticing the beam in their own.

What’s the point of difficult reading? Well, what’s the point of running five or ten miles? What’s the point of eating vegetables as opposed to ice cream or Doritos? Difficulty need not preclude enjoyment. And discipline in the present is often rewarded in the future. It very well may be that the complexity of the ideas you’re capable of understanding is influenced by how many complex ideas you attempt to understand. No matter how vehemently true believers in the magic of markets insist otherwise, markets don’t have minds. And though an individual’s intelligence need not be fixed a good way to ensure children never get any smarter than they already are is to make them feel fantastically wonderful about their mediocrity. We just have to hope that despite these ideological traps there are enough people out there determined to wrap their minds around complex situations depicted in complex narratives about complex people told in complex language, people who will in the process develop the types of minds and intelligence necessary to lead the rest of our lazy asses into a future that’s livable and enjoyable. For every John Galt, Tony Robbins, and Scheherazade, we may need at least half a Proust. We are still, however, left with quite a dilemma. Some authors really are just assholes who write worthless tomes designed to trick you into wasting your time. But some books that seem impenetrable on the first attempt will reward your efforts to decipher them. How do we get the rewards without wasting our time?

Can’t Win for Losing: Why There Are So Many Losers in Literature and Why It Has to Change

David Lurie’s position in Disgrace is similar to that of John Proctor in The Crucible (although this doesn’t come out nearly as much in the movie version). And it’s hard not to see feminism in its current manifestations—along with Marxism and postcolonialism—as a pernicious new breed of McCarthyism infecting academia and wreaking havoc with men and literature alike.

Ironically, the author of The Golden Notebook, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, and considered by many a “feminist bible,” happens to be an outspoken critic of feminism. When asked in a 1982 interview with Lesley Hazelton about her response to readers who felt some of her later works were betrayals of the women whose cause she once championed, Doris Lessing replied,

What the feminists want of me is something they haven't examined because it comes from religion. They want me to bear witness. What they would really like me to say is, ‘Ha, sisters, I stand with you side by side in your struggle toward the golden dawn where all those beastly men are no more.’ Do they really want people to make oversimplified statements about men and women? In fact, they do. I've come with great regret to this conclusion.

Lessing has also been accused of being overly harsh—“castrating”—to men, too many of whom she believes roll over a bit too easily when challenged by women aspiring to empowerment. As a famous novelist, however, who would go on to win the Nobel prize in literature in 2007, she got to visit a lot of schools, and it gradually dawned on her that it wasn’t so much that men were rolling over but rather that they were being trained from childhood to be ashamed of their maleness. In a lecture she gave to the Edinburgh book festival in 2001, she said,

Great things have been achieved through feminism. We now have pretty much equality at least on the pay and opportunities front, though almost nothing has been done on child care, the real liberation. We have many wonderful, clever, powerful women everywhere, but what is happening to men? Why did this have to be at the cost of men? I was in a class of nine- and 10-year-olds, girls and boys, and this young woman was telling these kids that the reason for wars was the innately violent nature of men. You could see the little girls, fat with complacency and conceit while the little boys sat there crumpled, apologising for their existence, thinking this was going to be the pattern of their lives.

Lessing describes how the teacher kept casting glances expectant of her approval as she excoriated these impressionable children.

Elaine Blair, in “Great American Losers,” an essay that’s equal parts trenchant and infuriatingly obtuse, describes a dynamic in contemporary fiction that’s similar to the one Lessing saw playing out in the classroom.

The man who feels himself unloved and unlovable—this is a character that we know well from the latest generation or two of American novels. His trials are often played for sympathetic laughs. His loserdom is total: it extends to his stunted career, his squalid living quarters, his deep unease in the world.

At the heart of this loserdom is his auto-manifesting knowledge that women don’t like him. As opposed to men of earlier generations who felt entitled to a woman’s respect and admiration, Blair sees this modern male character as being “the opposite of entitled: he approaches women cringingly, bracing for a slap.” This desperation on the part of male characters to avoid offending women, to prove themselves capable of sublimating their own masculinity so they can be worthy of them, finds its source in the authors themselves. Blair writes,

Our American male novelists, I suspect, are worried about being unloved as writers—specifically by the female reader. This is the larger humiliation looming behind the many smaller fictional humiliations of their heroes, and we can see it in the way the characters’ rituals of self-loathing are tacitly performed for the benefit of an imagined female audience.

Blair quotes a review David Foster Wallace wrote of a John Updike novel to illustrate how conscious males writing literature today are of their female readers’ hostility toward men who write about sex and women without apologizing for liking sex and women—sometimes even outside the bounds of caring, committed relationships. Labeling Updike as a “Great Male Narcissist,” a distinction he shares with writers like Philip Roth and Norman Mailer, Wallace writes,

Most of the literary readers I know personally are under forty, and a fair number are female, and none of them are big admirers of the postwar GMNs. But it’s John Updike in particular that a lot of them seem to hate. And not merely his books, for some reason—mention the poor man himself and you have to jump back:

“Just a penis with a thesaurus.”

“Has the son of a bitch ever had one unpublished thought?”

“Makes misogyny seem literary the same way Rush

[Limbaugh] makes fascism seem funny.”

And trust me: these are actual quotations, and I’ve heard even

worse ones, and they’re all usually accompanied by the sort of

facial expressions where you can tell there’s not going to be

any profit in appealing to the intentional fallacy or talking

about the sheer aesthetic pleasure of Updike’s prose.

Since Wallace is ready to “jump back” at the mere mention of Updike’s name, it’s no wonder he’s given to writing about characters who approach women “cringingly, bracing for a slap.”

Blair goes on to quote from Jonathan Franzen’s novel The Corrections, painting a plausible picture of male writers who fear not only that their books will be condemned if too misogynistic—a relative term which has come to mean "not as radically feminist as me"—but they themselves will be rejected. In Franzen’s novel, Chip Lambert has written a screenplay and asked his girlfriend Julia to give him her opinion. She holds off doing so, however, until after she breaks up with him and is on her way out the door. “For a woman reading it,” she says, “it’s sort of like the poultry department. Breast, breast, breast, thigh, leg” (26). Franzen describes his character’s response to the critique:

It seemed to Chip that Julia was leaving him because “The Academy Purple” had too many breast references and a draggy opening, and that if he could correct these few obvious problems, both on Julia’s copy of the script and, more important, on the copy he’d specially laser-printed on 24-pound ivory bond paper for [the film producer] Eden Procuro, there might be hope not only for his finances but also for his chances of ever again unfettering and fondling Julia’s own guileless, milk-white breasts. Which by this point in the day, as by late morning of almost every day in recent months, was one of the last activities on earth in which he could still reasonably expect to take solace for his failures. (28)

If you’re reading a literary work like The Corrections, chances are you’ve at some point sat in a literature class—or even a sociology or culture studies class—and been instructed that the proper way to fulfill your function as a reader is to critically assess the work in terms of how women (or minorities) are portrayed. Both Chip and Julia have sat through such classes. And you’re encouraged to express disapproval, even outrage if something like a traditional role is enacted—or, gasp, objectification occurs. Blair explains how this affects male novelists:

When you see the loser-figure in a novel, what you are seeing is a complicated bargain that goes something like this: yes, it is kind of immature and boorish to be thinking about sex all the time and ogling and objectifying women, but this is what we men sometimes do and we have to write about it. We fervently promise, however, to avoid the mistake of the late Updike novels: we will always, always, call our characters out when they’re being self-absorbed jerks and louts. We will make them comically pathetic, and punish them for their infractions a priori by making them undesirable to women, thus anticipating what we imagine will be your judgments, female reader. Then you and I, female reader, can share a laugh at the characters’ expense, and this will bring us closer together and forestall the dreaded possibility of your leaving me.

In other words, these male authors are the grownup versions of those poor school boys Lessing saw forced to apologize for their own existence. Indeed, you can feel this dynamic, this bargain, playing out when you’re reading these guys’ books. Blair’s description of the problem is spot on. Her theory of what caused it, however, is laughable.

Because of the GMNs, these two tendencies—heroic virility and sexist condescension—have lingered in our minds as somehow yoked together, and the succeeding generations of American male novelists have to some degree accepted the dyad as truth. Behind their skittishness is a fearful suspicion that if a man gets what he wants, sexually speaking, he is probably exploiting someone.

The dread of slipping down the slope from attraction to exploitation has nothing to do with John Updike. Rather, it is embedded in terms at the very core of feminist ideology. Misogyny, for instance, is frequently deemed an appropriate label for men who indulge in lustful gazing, even in private. And the term objectification implies that the female whose subjectivity isn’t being properly revered is the victim of oppression. The main problem with this idea—and there are several—is that the term objectification is synonymous with attraction. The deluge of details about the female body in fiction by male authors can just as easily be seen as a type of confession, an unburdening of guilt by the offering up of sins. The female readers respond by assigning the writers some form of penance, like never writing, never thinking like that again without flagellating themselves.

The conflict between healthy male desire and disapproving feminist prudery doesn’t just play out in the tortured psyches of geeky American male novelists. A.S. Byatt, in her Booker prize-winning novel Possession, satirizes the plight of scholars steeped in literary theories for being “papery” and sterile. But the novel ends with a male scholar named Roland overcoming his theory-induced self-consciousness to initiate sex with another scholar named Maud. Byatt describes the encounter:

And very slowly and with infinite gentle delays and delicate diversions and variations of indirect assault Roland finally, to use an outdated phrase, entered and took possession of all her white coolness that grew warm against him, so that there seemed to be no boundaries, and he heard, towards dawn, from a long way off, her clear voice crying out, uninhibited, unashamed, in pleasure and triumph. (551)

The literary critic Monica Flegel cites this passage as an example of how Byatt’s old-fashioned novel features “such negative qualities of the form as its misogyny and its omission of the lower class.” Flegel is particularly appalled by how “stereotypical gender roles are reaffirmed” in the sex scene. “Maud is reduced in the end,” Flegel alleges, “to being taken possession of by her lover…and assured that Roland will ‘take care of her.’” How, we may wonder, did a man assuring a woman he would take care of her become an act of misogyny?

Perhaps critics like Flegel occupy some radical fringe; Byatt’s book was after all a huge success with audiences and critics alike, and it did win Byatt the Booker. The novelist Martin Amis, however, isn’t one to describe his assaults as indirect. He routinely dares to feature men who actually do treat women poorly in his novels—without any authorial condemnation.

Martin Goff, the non-intervening director of the Booker Prize committee, tells the story of the 1989 controversy over whether or not Amis’s London Fields should be on the shortlist. Maggie Gee, a novelist, and Helen McNeil, a professor, simply couldn’t abide Amis’s treatment of his women characters. “It was an incredible row,” says Goff.

Maggie and Helen felt that Amis treated women appallingly in the book. That is not to say they thought books which treated women badly couldn't be good, they simply felt that the author should make it clear he didn't favour or bless that sort of treatment. Really, there was only two of them and they should have been outnumbered as the other three were in agreement, but such was the sheer force of their argument and passion that they won. David [Lodge] has told me he regrets it to this day, he feels he failed somehow by not saying, “It's two against three, Martin's on the list”.

In 2010, Amis explained his career-spanning failure to win a major literary award, despite enjoying robust book sales, thus:

There was a great fashion in the last century, and it's still with us, of the unenjoyable novel. And these are the novels which win prizes, because the committee thinks, “Well it's not at all enjoyable, and it isn't funny, therefore it must be very serious.”

Brits like Hilary Mantel, and especially Ian McEwan are working to turn this dreadful trend around. But when McEwan dared to write a novel about a neurosurgeon who prevails in the end over an afflicted, less privileged tormenter he was condemned by critic Jennifer Szalai in the pages of Harper’s Magazine for his “blithe, bourgeois sentiments.” If you’ve read Saturday, you know the sentiments are anything but blithe, and if you read Szalai’s review you’ll be taken aback by her articulate blindness.

Amis is probably right in suggesting that critics and award committees have a tendency to mistake misery for profundity. But his own case, along with several others like it, hint at something even more disturbing, a shift in the very idea of what role fictional narratives play in our lives.

The sad new reality is that, owing to the growing influence of ideologically extreme and idiotically self-righteous activist professors, literature is no longer read for pleasure and enrichment—it’s no longer even read as a challenging exercise in outgroup empathy. Instead, reading literature is supposed by many to be a ritual of male western penance. Prior to taking an interest in literary fiction, you must first be converted to the proper ideologies, made to feel sufficiently undeserving yet privileged, the beneficiary of a long history of theft and population displacement, the scion and gene-carrier of rapists and genocidaires—the horror, the horror. And you must be taught to systematically overlook and remain woefully oblivious of all the evidence that the Enlightenment was the best fucking thing that ever happened to the human species. Once you’re brainwashed into believing that so-called western culture is evil and that you’ve committed the original sin of having been born into it, you’re ready to perform your acts of contrition by reading horrendously boring fiction that forces you to acknowledge and reflect upon your own fallen state.

Fittingly, the apotheosis of this new literary tradition won the Booker in 1999, and its author, like Lessing, is a Nobel laureate. J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace chronicles in exquisite free indirect discourse the degradation of David Lurie, a white professor in Cape Town, South Africa, beginning with his somewhat pathetic seduction of black student, a crime for which he pays with the loss of his job, his pension, and his reputation, and moving on to the aftermath of his daughter’s rape at the hands of three black men who proceed to rob her, steal his car, douse him with spirits and light him on fire. What’s unsettling about the novel—and it is a profoundly unsettling novel—is that its structure implies that everything that David and Lucy suffer flows from his original offense of lusting after a young black woman. This woman, Melanie, is twenty years old, and though she is clearly reluctant at first to have sex with her teacher there’s never any force involved. At one point, she shows up at David’s house and asks to stay with him. It turns out she has a boyfriend who is refusing to let her leave him without a fight. It’s only after David unheroically tries to wash his hands of the affair to avoid further harassment from this boyfriend—while stooping so low as to insist that Melanie make up a test she missed in his class—that she files a complaint against him.

David immediately comes clean to university officials and admits to taking advantage of his position of authority. But he stalwartly refuses to apologize for his lust, or even for his seduction of the young woman. This refusal makes him complicit, the novel suggests, in all the atrocities of colonialism. As he’s awaiting a hearing to address Melanie’s complaint, David gets a message:

On campus it is Rape Awareness Week. Women Against Rape, WAR, announces a twenty-four-hour vigil in solidarity with “recent victims”. A pamphlet is slipped under his door: ‘WOMEN SPEAK OUT.’ Scrawled in pencil at the bottom is a message: ‘YOUR DAYS ARE OVER, CASANOVA.’ (43)

During the hearing, David confesses to doctoring the attendance ledgers and entering a false grade for Melanie. As the attendees become increasingly frustrated with what they take to be evasions, he goes on to confess to becoming “a servant of Eros” (52). But this confession only enrages the social sciences professor Farodia Rassool:

Yes, he says, he is guilty; but when we try to get specificity, all of a sudden it is not abuse of a young woman he is confessing to, just an impulse he could not resist, with no mention of the pain he has caused, no mention of the long history of exploitation of which this is part. (53)

There’s also no mention, of course, of the fact that already David has gone through more suffering than Melanie has, or that her boyfriend deserves a great deal of the blame, or that David is an individual, not a representative of his entire race who should be made to answer for the sins of his forefathers.

After resigning from his position in disgrace, David moves out to the country to live with his daughter on a small plot of land. The attack occurs only days after he’s arrived. David wants Lucy to pursue some sort of justice, but she refuses. He wants her to move away because she’s clearly not safe, but she refuses. She even goes so far as to accuse him of being in the wrong for believing he has any right to pronounce what happened an injustice—and for thinking it is his place to protect his daughter. And if there’s any doubt about the implication of David’s complicity she clears it up. As he’s pleading with her to move away, they begin talking about the rapists’ motivation. Lucy says to her father,

When it comes to men and sex, David, nothing surprises me anymore. Maybe, for men, hating the woman makes sex more exciting. You are a man, you ought to know. When you have sex with someone strange—when you trap her, hold her down, get her under you, put all your weight on her—isn’t it a bit like killing? Pushing the knife in; exiting afterwards, leaving the body behind covered in blood—doesn’t it feel like murder, like getting away with murder? (158)

The novel is so engrossing and so disturbing that it’s difficult to tell what the author’s position is vis à vis his protagonist’s degradation or complicity. You can’t help sympathizing with him and feeling his treatment at the hands of Melanie, Farodia, and Lucy is an injustice. But are you supposed to question that feeling in light of the violence Melanie is threatened with and Lucy is subjected to? Are you supposed to reappraise altogether your thinking about the very concept of justice in light of the atrocities of history? Are we to see David Lurie as an individual or as a representative of western male colonialism, deserving of whatever he’s made to suffer and more?

Personally, I think David Lurie’s position in Disgrace is similar to that of John Proctor in The Crucible (although this doesn’t come out nearly as much in the movie version). And it’s hard not to see feminism in its current manifestations—along with Marxism and postcolonialism—as a pernicious new breed of McCarthyism infecting academia and wreaking havoc with men and literature alike. It’s really no surprise at all that the most significant developments in the realm of narratives lately haven’t occurred in novels at all. Insofar as the cable series contributing to the new golden age of television can be said to adhere to a formula, it’s this: begin with a bad ass male lead who doesn’t apologize for his own existence and has no qualms about expressing his feelings toward women. As far as I know, these shows are just as popular with women viewers as they are with the guys.

When David first arrives at Lucy’s house, they take a walk and he tells her a story about a dog he remembers from a time when they lived in a neighborhood called Kenilworth.

It was a male. Whenever there was a bitch in the vicinity it would get excited and unmanageable, and with Pavlovian regularity the owners would beat it. This went on until the poor dog didn’t know what to do. At the smell of a bitch it would chase around the garden with its ears flat and its tail between its legs, whining, trying to hide…There was something so ignoble in the spectacle that I despaired. One can punish a dog, it seems to me, for an offence like chewing a slipper. A dog will accept the justice of that: a beating for a chewing. But desire is another story. No animal will accept the justice of being punished for following its instincts.

Lucy breaks in, “So males must be allowed to follow their instincts unchecked? Is that the moral?” David answers,

No, that is not the moral. What was ignoble about the Kenilworth spectacle was that the poor dog had begun to hate its own nature. It no longer needed to be beaten. It was ready to punish itself. At that point it would be better to shoot it.

“Or have it fixed,” Lucy offers. (90)

Also Read:

SABBATH SAYS: PHILIP ROTH AND THE DILEMMAS OF IDEOLOGICAL CASTRATION

And:

FROM DARWIN TO DR. SEUSS: DOUBLING DOWN ON THE DUMBEST APPROACH TO COMBATTING RACISM

The Storytelling Animal: a Light Read with Weighty Implications

The Storytelling Animal is not groundbreaking. But the style of the book contributes something both surprising and important. Gottschall could simply tell his readers that stories almost invariably feature come kind of conflict or trouble and then present evidence to support the assertion. Instead, he takes us on a tour from children’s highly gendered, highly trouble-laden play scenarios, through an examination of the most common themes enacted in dreams, through some thought experiments on how intensely boring so-called hyperrealism, or the rendering of real life as it actually occurs, in fiction would be. The effect is that we actually feel how odd it is to devote so much of our lives to obsessing over anxiety-inducing fantasies fraught with looming catastrophe.

A review of Jonathan Gottschall's The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human

Vivian Paley, like many other preschool and kindergarten teachers in the 1970s, was disturbed by how her young charges always separated themselves by gender at playtime. She was further disturbed by how closely the play of each gender group hewed to the old stereotypes about girls and boys. Unlike most other teachers, though, Paley tried to do something about it. Her 1984 book Boys and Girls: Superheroes in the Doll Corner demonstrates in microcosm how quixotic social reforms inspired by the assumption that all behaviors are shaped solely by upbringing and culture can be. Eventually, Paley realized that it wasn’t the children who needed to learn new ways of thinking and behaving, but herself. What happened in her classrooms in the late 70s, developmental psychologists have reliably determined, is the same thing that happens when you put kids together anywhere in the world. As Jonathan Gottschall explains,

Dozens of studies across five decades and a multitude of cultures have found essentially what Paley found in her Midwestern classroom: boys and girls spontaneously segregate themselves by sex; boys engage in more rough-and-tumble play; fantasy play is more frequent in girls, more sophisticated, and more focused on pretend parenting; boys are generally more aggressive and less nurturing than girls, with the differences being present and measurable by the seventeenth month of life. (39)

Paley’s study is one of several you probably wouldn’t expect to find discussed in a book about our human fascination with storytelling. But, as Gottschall makes clear in The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, there really aren’t many areas of human existence that aren’t relevant to a discussion of the role stories play in our lives. Those rowdy boys in Paley’s classes were playing recognizable characters from current action and sci-fi movies, and the fantasies of the girls were right out of Grimm’s fairy tales (it’s easy to see why people might assume these cultural staples were to blame for the sex differences). And the play itself was structured around one of the key ingredients—really the key ingredient—of any compelling story, trouble, whether in the form of invading pirates or people trying to poison babies.

The Storytelling Animal is the book to start with if you have yet to cut your teeth on any of the other recent efforts to bring the study of narrative into the realm of cognitive and evolutionary psychology. Gottschall covers many of the central themes of this burgeoning field without getting into the weedier territories of game theory or selection at multiple levels. While readers accustomed to more technical works may balk at wading through all the author’s anecdotes about his daughters, Gottschall’s keen sense of measure and the light touch of his prose keep the book from getting bogged down in frivolousness. This applies as well to the sections in which he succumbs to the temptation any writer faces when trying to explain one or another aspect of storytelling by making a few forays into penning abortive, experimental plots of his own.

None of the central theses of The Storytelling Animal is groundbreaking. But the style and layout of the book contribute something both surprising and important. Gottschall could simply tell his readers that stories almost invariably feature come kind of conflict or trouble and then present evidence to support the assertion, the way most science books do. Instead, he takes us on a tour from children’s highly gendered, highly trouble-laden play scenarios, through an examination of the most common themes enacted in dreams—which contra Freud are seldom centered on wish-fulfillment—through some thought experiments on how intensely boring so-called hyperrealism, or the rendering of real life as it actually occurs, in fiction would be (or actually is, if you’ve read any of D.F.Wallace’s last novel about an IRS clerk). The effect is that instead of simply having a new idea to toss around we actually feel how odd it is to devote so much of our lives to obsessing over anxiety-inducing fantasies fraught with looming catastrophe. And we appreciate just how integral story is to almost everything we do.

This gloss of Gottschall’s approach gives a sense of what is truly original about The Storytelling Animal—it doesn’t seal off narrative as discrete from other features of human existence but rather shows how stories permeate every aspect of our lives, from our dreams to our plans for the future, even our sense of our own identity. In a chapter titled “Life Stories,” Gottschall writes,

This need to see ourselves as the striving heroes of our own epics warps our sense of self. After all, it’s not easy to be a plausible protagonist. Fiction protagonists tend to be young, attractive, smart, and brave—all of the things that most of us aren’t. Fiction protagonists usually live interesting lives that are marked by intense conflict and drama. We don’t. Average Americans work retail or cubicle jobs and spend their nights watching protagonists do interesting things on television, while they eat pork rinds dipped in Miracle Whip. (171)

If you find this observation a tad unsettling, imagine it situated on a page underneath a mug shot of John Wayne Gacy with a caption explaining how he thought of himself “more as a victim than as a perpetrator.” For the most part, though, stories follow an easily identifiable moral logic, which Gottschall demonstrates with a short plot of his own based on the hypothetical situations Jonathan Haidt designed to induce moral dumbfounding. This almost inviolable moral underpinning of narratives suggests to Gottschall that one of the functions of stories is to encourage a sense of shared values and concern for the wider community, a role similar to the one D.S. Wilson sees religion as having played, and continuing to play in human evolution.

Though Gottschall stays away from the inside baseball stuff for the most part, he does come down firmly on one issue in opposition to at least one of the leading lights of the field. Gottschall imagines a future “exodus” from the real world into virtual story realms that are much closer to the holodecks of Star Trek than to current World of Warcraft interfaces. The assumption here is that people’s emotional involvement with stories results from audience members imagining themselves to be the protagonist. But interactive videogames are probably much closer to actual wish-fulfillment than the more passive approaches to attending to a story—hence the god-like powers and grandiose speechifying.

William Flesch challenges the identification theory in his own (much more technical) book Comeuppance. He points out that films that have experimented with a first-person approach to camera work failed to capture audiences (think of the complicated contraption that filmed Will Smith’s face as he was running from the zombies in I am Legend). Flesch writes, “If I imagined I were a character, I could not see her face; thus seeing her face means I must have a perspective on her that prevents perfect (naïve) identification” (16). One of the ways we sympathize with one another, though, is to mirror them—to feel, at least to some degree, their pain. That makes the issue a complicated one. Flesch believes our emotional involvement comes not from identification but from a desire to see virtuous characters come through the troubles of the plot unharmed, vindicated, maybe even rewarded. Attending to a story therefore entails tracking characters' interactions to see if they are in fact virtuous, then hoping desperately to see their virtue rewarded.

Gottschall does his best to avoid dismissing the typical obsessive Larper (live-action role player) as the “stereotypical Dungeons and Dragons player” who “is a pimply, introverted boy who isn’t cool and can’t play sports or attract girls” (190). And he does his best to end his book on an optimistic note. But the exodus he writes about may be an example of another phenomenon he discusses. First the optimism:

Humans evolved to crave story. This craving has, on the whole, been a good thing for us. Stories give us pleasure and instruction. They simulate worlds so we can live better in this one. They help bind us into communities and define us as cultures. Stories have been a great boon to our species. (197)

But he then makes an analogy with food cravings, which likewise evolved to serve a beneficial function yet in the modern world are wreaking havoc with our health. Just as there is junk food, so there is such a thing as “junk story,” possibly leading to what Brian Boyd, another luminary in evolutionary criticism, calls a “mental diabetes epidemic” (198). In the context of America’s current education woes, and with how easy it is to conjure images of glazy-eyed zombie students, the idea that video games and shows like Jersey Shore are “the story equivalent of deep-fried Twinkies” (197) makes an unnerving amount of sense.

Here, as in the section on how our personal histories are more fictionalized rewritings than accurate recordings, Gottschall manages to achieve something the playful tone and off-handed experimentation don't prepare you for. The surprising accomplishment of this unassuming little book (200 pages) is that it never stops being a light read even as it takes on discoveries with extremely weighty implications. The temptation to eat deep-fried Twinkies is only going to get more powerful as story-delivery systems become more technologically advanced. Might we have already begun the zombie apocalypse without anyone noticing—and, if so, are there already heroes working to save us we won’t recognize until long after the struggle has ended and we’ve begun weaving its history into a workable narrative, a legend?

Also read:

WHAT IS A STORY? AND WHAT ARE YOU SUPPOSED TO DO WITH ONE?

And:

HOW TO GET KIDS TO READ LITERATURE WITHOUT MAKING THEM HATE IT

Madness and Bliss: Critical vs Primitive Readings in A.S. Byatt's Possession: A Romance 2

Critics responded to A.S. Byatt’s challenge to their theories in her book Possession by insisting that the work fails to achieve high-brow status and fails to do anything but bolster old-fashioned notions about stories and language—not to mention the roles of men and women. What they don’t realize is how silly their theories come across to the non-indoctrinated.

Read part one.

The critical responses to the challenges posed by Byatt in Possession fit neatly within the novel’s satire. Louise Yelin, for instance, unselfconsciously divides the audience for the novel into “middlebrow readers” and “the culturally literate” (38), placing herself in the latter category. She overlooks Byatt’s challenge to her methods of criticism and the ideologies underpinning them, for the most part, and suggests that several of the themes, like ventriloquism, actually support poststructuralist philosophy. Still, Yelin worries about the novel’s “homophobic implications” (39). (A lesbian, formerly straight character takes up with a man in the end, and Christabel LaMotte’s female lover commits suicide after the dissolution of their relationship, but no one actually expresses any fear or hatred of homosexuals.) Yelin then takes it upon herself to “suggest directions that our work might take” while avoiding the “critical wilderness” Byatt identifies. She proposes a critical approach to a novel that “exposes its dependencies on the bourgeois, patriarchal, and colonial economies that underwrite” it (40). And since all fiction fails to give voice to one or another oppressed minority, it is the critic’s responsibility to “expose the complicity of those effacements in the larger order that they simultaneously distort and reproduce” (41). This is not in fact a response to Byatt’s undermining of critical theories; it is instead an uncritical reassertion of their importance.

Yelin and several other critics respond to Possession as if Byatt had suggested that “culturally literate” readers should momentarily push to the back of their minds what they know about how literature is complicit in various forms of political oppression so they can get more enjoyment from their reading. This response is symptomatic of an astonishing inability to even imagine what the novel is really inviting literary scholars to imagine—that the theories implicating literature are flat-out wrong. Monica Flegel for instance writes that “What must be privileged and what must be sacrificed in order for Byatt’s Edenic reading (and living) state to be achieved may give some indication of Byatt’s own conventionalizing agenda, and the negative enchantment that her particular fairy tale offers” (414). Flegel goes on to show that she does in fact appreciate the satire on academic critics; she even sympathizes with the nostalgia for simpler times, before political readings became mandatory. But she ends her critical essay with another reassertion of the political, accusing Byatt of “replicating” through her old-fashioned novel “such negative qualities of the form as its misogyny and its omission of the lower class.” Flegel is particularly appalled by Maud’s treatment in the final scene, since, she claims, “stereotypical gender roles are reaffirmed” (428). “Maud is reduced in the end,” Flegel alleges, “to being taken possession of by her lover…and assured that Roland will ‘take care of her’” (429). This interpretation places Flegel in the company of the feminists in the novel who hiss at Maud for trying to please men, forcing her to bind her head.

Flegel believes that her analysis proves Byatt is guilty of misogyny and mistreatment of the poor. “Byatt urges us to leave behind critical readings and embrace reading for enjoyment,” she warns her fellow critics, “but the narrative she offers shows just how much is at stake when we leave criticism behind” (429). Flegel quotes Yelin to the effect that Possession is “seductive,” and goes on to declaim that

it is naïve, and unethical, to see the kind of reading that Byatt offers as happy. To return to an Edenic state of reading, we must first believe that such a state truly existed and that it was always open to all readers of every class, gender, and race. Obviously, such a belief cannot be held, not because we have lost the ability to believe, but because such a space never really did exist. (430)

In her preening self-righteous zealotry, Flegel represents a current in modern criticism that’s only slightly more extreme than that represented by Byatt’s misguided but generally harmless scholars. The step from using dubious theories to decode alleged justifications for political oppression in literature to Flegel’s frightening brand of absurd condemnatory moralizing leveled at authors and readers alike is a short one.

Another way critics have attempted to respond to Byatt’s challenge is by denying that she is in fact making any such challenge. Christien Franken suggests that Byatt’s problems with theories like poststructuralism stem from her dual identity as a critic and an author. In a lecture Byatt once gave titled “Identity and the Writer” which was later published as an essay, Franken finds what she believes is evidence of poststructuralist thinking, even though Byatt denies taking the theory seriously. Franken believes that in the essay, “the affinity between post-structuralism and her own thought on authorship is affirmed and then again denied” (18). Her explanation is that the critic in A.S. Byatt begins her lecture “Identity and the Writer” with a recognition of her own intellectual affinity with post-structuralist theories which criticize the paramount importance of “the author.”

The writer in Byatt feels threatened by the same post-structuralist criticism. (17)

Franken claims that this ambivalence runs throughout all of Byatt’s fiction and criticism. But Ann Marie Adams disagrees, writing that “When Byatt does delve into poststructuralist theory in this essay, she does so only to articulate what ‘threatens’ and ‘beleaguers’ her as a writer, not to productively help her identify the true ‘identity’ of the writer” (349). In Adams view, Byatt belongs in the humanist tradition of criticism going back to Matthew Arnold and the romantics. In her own response to Byatt, Adams manages to come closer than any of her fellow critics to being able to imagine that the ascendant literary theories are simply wrong. But her obvious admiration for Byatt doesn’t prevent her from suggesting that “Yelin and Flegel are right to note that the conclusion of Possession, with its focus on closure and seeming transcendence of critical anxiety, affords a particularly ‘seductive’ and ideologically laden pleasure to academic readers” (120). And, while she seems to find some value in Arnoldian approaches, she fails to engage in any serious reassessment of the theories Byatt targets.

Frederick Holmes, in his attempt to explain Byatt’s attitude toward history as evidenced by the novel, agrees with the critics who see in Possession clear signs of the author’s embrace of postmodernism in spite of the parody and explicit disavowals. “It is important to acknowledge,” he writes,

that the liberation provided by Roland’s imagination from the previously discussed sterility of his intellectual sophistication is never satisfactorily accounted for in rational terms. It is not clear how he overcomes the post-structuralist positions on language, authorship, and identity. His claim that some signifiers are concretely attached to signifieds is simply asserted, not argued for. (330)

While Holmes is probably mistaken in taking this absence of rational justification as a tacit endorsement of the abandoned theory, the observation is the nearest any of the critics comes to a rebuttal of Byatt’s challenge. What Holmes is forgetting, though, is that structuralist and poststructuralist theorists themselves, from Saussure through Derrida, have been insisting on the inadequacy of language to describe the real world, a radical idea that flies in the face of every human’s lived experience, without ever providing any rational, empirical, or even coherent support for the departure.

The stark irony to which Holmes is completely oblivious is that he’s asking for a rational justification to abandon a theory that proclaims such justification impossible. The burden remains on poststructuralists to prove that people shouldn’t trust their own experiences with language. And it is precisely this disconnect with experience that Byatt shows to be problematic.

Holmes, like the other critics, simply can’t imagine that critical theories have absolutely no validity, so he’s forced to read into the novel the same chimerical ambivalence Franken tries so desperately to prove.

Roland’s dramatic alteration is validated by the very sort of emotional or existential experience that critical theory has conditioned him to dismiss as insubstantial. We might account for Roland’s shift by positing, not a rejection of his earlier thinking, but a recognition that his psychological well-being depends on his living as if such powerful emotional experiences had an unquestioned reality. (330)

Adams quotes from an interview in which Byatt discusses her inspiration for the characters in Possession, saying, “poor moderns are always asking themselves so many questions about whether their actions are real and whether what they say can be thought to be true […] that they become rather papery and are miserably aware of this” (111-2). Byatt believes this type of self-doubt is unnecessary. Indeed, Maud’s notion that “there isn’t a unitary ego” (290) and Roland’s thinking of the “idea of his ‘self’ as an illusion” (459)—not to mention Holmes’s conviction that emotional experiences are somehow unreal—are simple examples of the reductionist fallacy. While it is true that an individual’s consciousness and sense of self rest on a substrate of unconscious mental processes and mechanics that can be traced all the way down to the firing of neurons, to suggest this mechanical accounting somehow delegitimizes selfhood is akin to saying that water being made up of hydrogen and oxygen atoms means the feeling of wetness can only be an illusion.

Just as silly are the ideas that romantic love is a “suspect ideological construct” (290), as Maud calls it, and that “the expectations of Romance control almost everyone in the Western world” (460), as Roland suggests. Anthropologist Helen Fisher writes in her book Anatomy of Love, “some Westerners have come to believe that romantic love is an invention of the troubadours… I find this preposterous. Romantic love is far more widespread” (49). After a long list of examples of love-strickenness from all over the world from west to east to everywhere in-between, Fisher concludes that it “must be a universal human trait” (50). Scientists have found empirical support as well for Roland’s discovery that words can in fact refer to real things. Psychologist Nicole Speer and her colleagues used fMRI to scan people’s brains as they read stories. The actions and descriptions on the page activated the same parts of the brain as witnessing or perceiving their counterparts in reality. The researchers report, “Different brain regions track different aspects of a story, such as a character’s physical location or current goals. Some of these regions mirror those involved when people perform, imagine, or observe similar real-world activities” (989).

Critics like Flegel insist on joyless reading because happy endings necessarily overlook the injustices of the world. But this is like saying anyone who savors a meal is complicit in world hunger (or for that matter anyone who enjoys reading about a character savoring a meal). If feminist poststructuralists were right about how language functions as a vehicle for oppressive ideologies, then the most literate societies would be the most oppressive, instead of the other way around. Jacques Lacan is the theorist Byatt has the most fun with in Possession—and he is also the main target of the book Fashionable Nonsense:Postmodern Intellectuals’ Abuse of Science by the scientists Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont. “According to his disciples,” they write, Lacan “revolutionized the theory and practice of psychoanalysis; according to his critics, he is a charlatan and his writings are pure verbiage” (18). After assessing Lacan’s use of concepts in topological mathematics, like the Mobius strip, which he sets up as analogies for various aspects of the human psyche, Sokal and Bricmont conclude that Lacan’s ideas are complete nonsense. They write,

The most striking aspect of Lacan and his disciples is probably their attitude toward science, and the extreme privilege they accord to “theory”… at the expense of observations and experiments… Before launching into vast theoretical generalizations, it might be prudent to check the empirical adequacy of at least some of its propositions. But, in Lacan’s writings, one finds mainly quotations and analyses of texts and concepts. (37)

Sokal and Bricmont wonder if the abuses of theorists like Lacan “arise from conscious fraud, self-deception, or perhaps a combination of the two” (6). The question resonates with the poem Randolph Henry Ash wrote about his experience exposing a supposed spiritualist as a fraud, in which he has a mentor assure her protégée, a fledgling spiritualist with qualms about engaging in deception, “All Mages have been tricksters” (444).

There’s even some evidence that Byatt is right about postmodern thinking making academics into “papery” people. In a 2006 lecture titled “The Inhumanity of the Humanities,” William van Peer reports on research he conducted with a former student comparing the emotional intelligence of students in the humanities to students in the natural sciences.

Although the psychologists Raymond Mar and Keith Oately (407) have demonstrated that reading fiction increases empathy and emotional intelligence, van Peer found that humanities students had no advantage in emotional intelligence over students of natural science. In fact, there was a weak trend in the opposite direction—this despite the fact that the humanities students were reading more fiction. Van Peer attributes the deficit to common academic approaches to literature:

Consider the ills flowing from postmodern approaches, the “posthuman”: this usually involves the hegemony of “race/class/gender” in which literary texts are treated with suspicion. Here is a major source of that loss of emotional connection between student and literature. How can one expect a certain humanity to grow in students if they are continuously instructed to distrust authors and texts? (8)

Whether it derives from her early reading of Arnold and his successors, as Adams suggests, or simply from her own artistic and readerly sensibilities, Byatt has an intense desire to revive that very humanity so many academics sacrifice on the altar of postmodern theory. Critical theory urges students to assume that any discussion of humanity, or universal traits, or human nature can only be exclusionary, oppressive, and, in Flegel’s words, “naïve” and “unethical.” The cognitive linguist Steven Pinker devotes his book The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature to debunking the radical cultural and linguistic determinism that is the foundation of modern literary theory. In a section on the arts, Pinker credits Byatt for playing a leading role in what he characterizes as a “revolt”:

Museum-goers have become bored with the umpteenth exhibit on the female body featuring dismembered torsos or hundreds of pounds of lard chewed up and spat out by the artist. Graduate students in the humanities are grumbling in emails and conference hallways about being locked out of the job market unless they write in gibberish while randomly dropping the names of authorities like Foucault and Butler. Maverick scholars are doffing the blinders that prevented them from looking at exciting developments in the sciences of human nature. And younger artists are wondering how the art world got itself into the bizarre place in which beauty is a dirty word. (Pinker 416)

There are resonances with Roland Mitchell’s complaints about how psychoanalysis transforms perceptions of landscapes in Pinker’s characterization of modern art. And the idea that beauty has become a dirty word is underscored by the critical condemnations of Byatt’s “fairy tale ending.” Pinker goes on to quote Byatt’s response in New York Times Magazine to the question of what the best story ever told was.

Her answer—The Arabian Nights:

The stories in “The Thousand and One Nights”… are about storytelling without ever ceasing to be stories about love and life and death and money and food and other human necessities. Narration is as much a part of human nature as breath and the circulation of the blood. Modernist literature tried to do away with storytelling, which it thought vulgar, replacing it with flashbacks, epiphanies, streams of consciousness. But storytelling is intrinsic to biological time, which we cannot escape. Life, Pascal said, is like living in a prison from which every day fellow prisoners are taken away to be executed. We are all, like Scheherazade, under sentences of death, and we all think of our lives as narratives, with beginnings, middles, and ends. (quoted in Pinker 419)

Byatt’s satire of papery scholars and her portrayals of her characters’ transcendence of nonsensical theories are but the simplest and most direct ways she celebrates the power of language to transport readers—and the power of stories to possess them. Though she incorporates an array of diverse genres, from letters to poems to diaries, and though some of the excerpts’ meanings subtly change in light of discoveries about their authors’ histories, all these disparate parts nonetheless “hook together,” collaborating in the telling of this magnificent tale. This cooperation would be impossible if the postmodern truism about the medium being the message were actually true. Meanwhile, the novel’s intimate engagement with the mythologies of wide-ranging cultures thoroughly undermines the paradigm according to which myths are deterministic “repeating patterns” imposed on individuals, showing instead that these stories simultaneously emerge from and lend meaning to our common human experiences. As the critical responses to Possession make abundantly clear, current literary theories are completely inadequate in any attempt to arrive at an understanding of Byatt’s work. While new theories may be better suited to the task, it is incumbent on us to put forth a good faith effort to imagine the possibility that true appreciation of this and other works of literature will come only after we’ve done away with theory altogether.

Madness and Bliss: Critical versus Primitive Readings in A.S. Byatt’s Possession: a Romance

Possession can be read as the novelist’s narrative challenge to the ascendant critical theories, an “undermining of facile illusions” about language and culture and politics—a literary refutation of current approaches to literary criticism.

Part 1 of 2