HUNGER GAME THEORY: Post-Apocalyptic Fiction and the Rebirth of Humanity

The appeal of post-apocalyptic stories stems from the joy of experiencing anew the birth of humanity. The renaissance never occurs in M.T. Anderson’s Feed, in which the main character is rendered hopelessly complacent by the entertainment and advertising beamed directly into his brain. And it is that very complacency, the product of our modern civilization's unfathomable complexity, that most threatens our sense of our own humanity. There was likely a time, though, when small groups composed of members of our species were beset by outside groups composed of individuals of a different nature, a nature that when juxtaposed with ours left no doubt as to who the humans were.

In Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen reflects on how the life-or-death stakes of the contest she and her fellow “tributes” are made to participate in can transform teenage boys and girls into crazed killers. She’s been brought to a high-tech mega-city from District 12, a mining town as quaint as the so-called Capitol is futuristic. Peeta Mellark, who was chosen by lottery as the other half of the boy-girl pair of tributes from the district, has just said to her, “I want to die as myself…I don’t want them to change me in there. Turn me into some kind of monster that I’m not.” Peeta also wants “to show the Capitol they don’t own me. That I’m more than just a piece in their Games.” The idea startles Katniss, who at this point is thinking of nothing but surviving the games—knowing full well that there are twenty-two more tributes and only one will be allowed to leave the arena alive. Annoyed by Peeta’s pronouncement of a higher purpose, she thinks,

We will see how high and mighty he is when he’s faced with life and death. He’ll probably turn into one of those raging beast tributes, the kind who tries to eat someone’s heart after they’ve killed them. There was a guy like that a few years ago from District 6 called Titus. He went completely savage and the Gamemakers had to have him stunned with electric guns to collect the bodies of the players he’d killed before he ate them. There are no rules in the arena, but cannibalism doesn’t play well with the Capitol audience, so they tried to head it off. (141-3)

Cannibalism is the ultimate relinquishing of the mantle of humanity because it entails denying the humanity of those being hunted for food. It’s the most basic form of selfishness: I kill you so I can live.

The threat posed to humanity by hunger is also the main theme of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, the story of a father and son wandering around the ruins of a collapsed civilization. The two routinely search abandoned houses for food and supplies, and in one they discover a bunch of people locked in a cellar. The gruesome clue to the mystery of why they’re being kept is that some have limbs amputated. The men keeping them are devouring the living bodies a piece at a time. After a harrowing escape, the boy, understandably disturbed, asks, “They’re going to kill those people, arent they?” His father, trying to protect him from the harsh reality, answers yes, but tries to be evasive, leading to this exchange:

Why do they have to do that?

I dont know.

Are they going to eat them?

I dont know.

They’re going to eat them, arent they?

Yes.

And we couldnt help them because then they’d eat us too.

Yes.

And that’s why we couldnt help them.

Yes.

Okay.

But of course it’s not okay. After they’ve put some more distance between them and the human abattoir, the boy starts to cry. His father presses him to explain what’s wrong:

Just tell me.

We wouldnt ever eat anybody, would we?

No. Of course not.

Even if we were starving?

We’re starving now.

You said we werent.

I said we werent dying. I didn’t say we werent starving.

But we wouldnt.

No. We wouldnt.

No matter what.

No. No matter what.

Because we’re the good guys.

Yes.

And we’re carrying the fire.

And we’re carrying the fire. Yes.

Okay. (127-9)

And this time it actually is okay because the boy, like Peeta Mellark, has made it clear that if the choice is between dying and becoming a monster he wants to die.

This preference for death over depredation of others is one of the hallmarks of humanity, and it poses a major difficulty for economists and evolutionary biologists alike. How could this type of selflessness possibly evolve?

John von Neumann, one of the founders of game theory, served an important role in developing the policies that have so far prevented the real life apocalypse from taking place. He is credited with the strategy of Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD (he liked amusing acronyms), that prevailed during the Cold War. As the name implies, the goal was to assure the Soviets that if they attacked us everyone would die. Since the U.S. knew the same was true of any of our own plans to attack the Soviets, a tense peace, or Cold War, was the inevitable result. But von Neumann was not at all content with this peace. He devoted his twilight years to pushing for the development of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) that would allow the U.S. to bomb Russia without giving the Soviets a chance to respond. In 1950, he made the infamous remark that inspired Dr. Strangelove: “If you say why not bomb them tomorrow, I say, why not today. If you say today at five o’clock, I say why not one o’clock?”

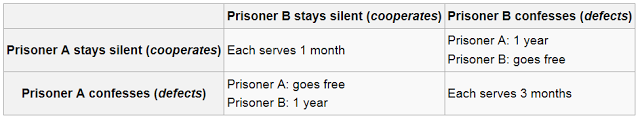

Von Neumann’s eagerness to hit the Russians first was based on the logic of game theory, and that same logic is at play in The Hunger Games and other post-apocalyptic fiction. The problem with cooperation, whether between rival nations or between individual competitors in a game of life-or-death, is that it requires trust—and once one player begins to trust the other he or see becomes vulnerable to exploitation, the proverbial stab in the back from the person who’s supposed to be watching it. Game theorists model this dynamic with a thought experiment called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine two criminals are captured and taken to separate interrogation rooms. Each criminal has the option of either cooperating with the other criminal by remaining silent or betraying him or her by confessing. Here’s a graph of the possible outcomes:

No matter what the other player does, each of them achieves a better outcome by confessing. Von Neumann saw the standoff between the U.S. and the Soviets as a Prisoner’s Dilemma; by not launching nukes, each side was cooperating with the other. Eventually, though, one of them had to realize that the only rational thing to do was be the first to defect.

But the way humans play games is a bit different. As it turned out, von Neumann was wrong about the game theory implications of the Cold War—neither side ever did pull the trigger; both prisoners kept their mouth shut. In Collins' novel, Katniss faces a Prisoner's Dilemma every time she encounters another tribute who may be willing to team up with her in the hunger game. The graph for her and Peeta looks like this:

In the context of the hunger games, then, it makes sense to team up with rivals as long as they have useful skills, knowledge, or strength. Each tribute knows, furthermore, that as long as he or she is useful to a teammate, it would be irrational for that teammate to defect.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma logic gets much more complicated when you start having players try to solve it over multiple rounds of play. Game theorists refer to each time a player has to make a choice as an iteration. And to model human cooperative behavior you have to not only have multiple iterations but also find a way to factor in each player’s awareness of how rivals have responded to the dilemma in the past. Humans have reputations. Katniss, for instance, doesn’t trust the Career tributes because they have a reputation for being ruthless. She even begins to suspect Peeta when she sees that he’s teamed up with the Careers. (His knowledge of Katniss is a resource to them, but he’s using that knowledge in an irrational way—to protect her instead of himself.) On the other hand, Katniss trusts Rue because she's young and dependent—and because she comes from an adjacent district not known for sending tributes who are cold-blooded.

When you have multiple iterations and reputations, you also open the door for punishments and rewards. At the most basic level, people reward those who they witness cooperating by being more willing to cooperate with them. As we read or watch The Hunger Games, we can actually experience the emotional shift that occurs in ourselves as we witness Katniss’s cooperative behavior.

People punish those who defect by being especially reluctant to trust them. At this point, the analysis is still within the realm of the purely selfish and rational. But you can’t stay in that realm for very long when you’re talking about the ways humans respond to one another.

Each time Katniss encounters another tribute in the games she faces a Prisoner’s Dilemma. Until the final round, the hunger games are not a zero-sum contest—which means that a gain for one doesn’t necessarily mean a loss for the other. Ultimately, of course, Katniss and Peeta are playing a zero-sum game; since only one tribute can win, one of any two surviving players at the end will have to kill the other (or let him die). Every time one tribute kills another, the math of the Prisoner’s Dilemma has to be adjusted. Peeta, for instance, wouldn’t want to betray Katniss early on, while there are still several tributes trying to kill them, but he would want to balance the benefits of her resources with whatever advantage he could gain from her unsuspecting trust—so as they approach the last few tributes, his temptation to betray her gets stronger. Of course, Katniss knows this too, and so the same logic applies for her.

As everyone who’s read the novel or seen the movie knows, however, this isn’t how either Peeta or Katniss plays in the hunger games. And we already have an idea of why that is: Peeta has said he doesn’t want to let the games turn him into a monster. Figuring out the calculus of the most rational decisions is well and good, but humans are often moved by their emotions—fear, affection, guilt, indebtedness, love, rage—to behave in ways that are completely irrational—at least in the near term. Peeta is in love with Katniss, and though she doesn’t really quite trust him at first, she proves willing to sacrifice herself in order to help him survive. This goes well beyond cooperation to serve purely selfish interests.

Many evolutionary theorists believe that at some point in our evolutionary history, humans began competing with each other to see who could be the most cooperative. This paradoxical idea emerges out of a type of interaction between and among individuals called costly signaling. Many social creatures must decide who among their conspecifics would make the best allies. And all sexually reproducing animals have to have some way to decide with whom to mate. Determining who would make the best ally or who would be the fittest mate is so important that only the most reliable signals are given any heed. What makes the signals reliable is their cost—only the fittest can afford to engage in costly signaling. Some animals have elaborate feathers that are conspicuous to predators; others have massive antlers. This is known as the handicap principle. In humans, the theory goes, altruism somehow emerged as a costly signal, so that the fittest demonstrate their fitness by engaging in behaviors that benefit others to their own detriment. The boy in The Road, for instance, isn’t just upset by the prospect of having to turn to canibalism himself; he’s sad that he and his father weren’t able to help the other people they found locked in the cellar.

We can’t help feeling strong positive emotions toward altruists. Katniss wins over readers and viewers the moment she volunteers to serve as tribute in place of her younger sister, whose name was picked in the lottery. What’s interesting, though, is that at several points in the story Katniss actually does engage in purely rational strategizing. She doesn’t attempt to help Peeta for a long time after she finds out he’s been wounded trying to protect her—why would she when they’re only going to have to fight each other in later rounds? But when it really comes down to it, when it really matters most, both Katniss and Peeta demonstrate that they’re willing to protect one another even at a cost to themselves.

The birth of humanity occurred, somewhat figuratively, when people refused to play the game of me versus you and determined instead to play us versus them. Humans don’t like zero-sum games, and whenever possible they try to change to the rules so there can be more than one winner. To do that, though, they have to make it clear that they would rather die than betray their teammates. In The Road, the father and his son continue to carry the fire, and in The Hunger Games Peeta gets his chance to show he’d rather die than be turned into a monster. By the end of the story, it’s really no surprise what Katniss choses to do either. Saving her sister may not have been purely altruistic from a genetic standpoint. But Peeta isn’t related to her, nor is he her only—or even her most eligible—suitor. Still, her moments of cold strategizing notwithstanding, we've had her picked as an altruist all along.

Of course, humanity may have begun with the sense that it’s us versus them, but as it’s matured the us has grown to encompass an ever wider assortment of people and the them has receded to include more and more circumscribed groups of evil-doers. Unfortunately, there are still all too many people who are overly eager to treat unfamiliar groups as rival tribes, and all too many people who believe that the best governing principle for society is competition—the war of all against all. Altruism is one of the main hallmarks of humanity, and yet some people are simply more altruistic than others. Let’s just hope that it doesn’t come down to us versus them…again.

Also read

And: