READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Why Tamsin Shaw Imagines the Psychologists Are Taking Power

Upon first reading Shaw’s piece, I dismissed it as a particularly unscrupulous bit of interdepartmental tribalism—a philosopher bemoaning the encroachment by pesky upstart scientists into what was formerly the bailiwick of philosophers. But then a line in Shaw’s attempted rebuttal of Haidt and Pinker’s letter sent me back to the original essay, and this time around I recognized it as a manifestation of a more widespread trend among scholars, and a rather unscholarly one at that.

Tamsin Shaw’s essay in the February 25th issue of The New York Review of Books, provocatively titled “The Psychologists Take Power,” is no more scholarly than your average political attack ad, nor is it any more credible. (The article is available online, but I won’t lend it further visibility to search engines by linking to it here.) Two of the psychologists maligned in the essay, Jonathan Haidt and Steven Pinker, recently contributed a letter to the editors which effectively highlights Shaw’s faulty reasoning and myriad distortions, describing how she “prosecutes her case by citation-free attribution, spurious dichotomies, and standards of guilt by association that make Joseph McCarthy look like Sherlock Holmes” (82).

Upon first reading Shaw’s piece, I dismissed it as a particularly unscrupulous bit of interdepartmental tribalism—a philosopher bemoaning the encroachment by pesky upstart scientists into what was formerly the bailiwick of philosophers. But then a line in Shaw’s attempted rebuttal of Haidt and Pinker’s letter sent me back to the original essay, and this time around I recognized it as a manifestation of a more widespread trend among scholars, and a rather unscholarly one at that.

Shaw begins her article by accusing a handful of psychologists of exceeding the bounds of their official remit. These researchers have risen to prominence in recent years through their studies into human morality. But now, instead of restricting themselves, as responsible scientists would, to describing how we make moral judgements and attempting to explain why we respond to moral dilemmas the way we do, these psychologists have begun arrogating moral authority to themselves. They’ve begun, in other words, trying to tell us how we should reason morally—according to Shaw anyway. Her article then progresses through shady innuendo and arguments based on what Haidt and Pinker call “guilt through imaginability” to connect this group of authors to the CIA’s program of “enhanced interrogation,” i.e. torture, which culminated in such atrocities as those committed in the prisons at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay.

Shaw’s sole piece of evidence comes from a report that was commissioned by the American Psychological Association. David Hoffman and his fellow investigators did indeed find that two members of the APA played a critical role in developing the interrogation methods used by the CIA, and they had the sanction of top officials. Neither of the two, however, and none of those officials authored any of the books on moral psychology that Shaw is supposedly reviewing. In the report’s conclusion, the investigators describe the responses of clinical psychologists who “feel physically sick when they think about the involvement of psychologists intentionally using harsh interrogation techniques.” Shaw writes,

It is easy to imagine the psychologists who claim to be moral experts dismissing such a reaction as an unreliable “gut response” that must be overridden by more sophisticated reasoning. But a thorough distrust of rapid, emotional responses might well leave human beings without a moral compass sufficiently strong to guide them through times of crisis, when our judgement is most severely challenged, or to compete with powerful nonmoral motivations. (39)

What she’s referring to here is the two-system model of moral reasoning which posits a rapid, intuitive system, programmed in large part by our genetic inheritance but with some cultural variation in its expression, matched against a more effort-based, cerebral system that requires the application of complex reasoning.

But it must be noted that nowhere does any of the authors she’s reviewing make a case for a “thorough distrust of rapid, emotional responses.” Their positions are far more nuanced, and Haidt in fact argues in his book The Righteous Mind that liberals could benefit from paying more heed to some of their moral instincts—a case that Shaw herself summarizes in her essay when she’s trying to paint him as an overly “didactic” conservative.

Haidt and Pinker’s response to Shaw’s argument by imaginability was to simply ask the other five authors she insinuates support torture whether they indeed reacted the way she describes. They write, “The results: seven out of seven said ‘no’” (82). These authors’ further responses to the question offer a good opportunity to expose just how off-base Shaw’s simplistic characterizations are.

None of these psychologists believes that a reaction of physical revulsion must be overridden or should be thoroughly distrusted. But several pointed out that in the past, people have felt physically sick upon contemplating homosexuality, interracial marriage, vaccination, and other morally unexceptionable acts, so gut feelings alone cannot constitute a “moral compass.” Nor is the case against “enhanced interrogation” so fragile, as Shaw implies, that it has to rest on gut feelings: the moral arguments against torture are overwhelming. So while primitive physical revulsion may serve as an early warning signal indicating that some practice calls for moral scrutiny, it is “the more sophisticated reasoning” that should guide us through times of crisis. (82-emphasis in original)

One phrase that should stand out here is “the moral arguments against torture are overwhelming.” Shaw is supposedly writing about a takeover by psychologists who advocate torture—but none of them actually advocates torture. And, having read four of the six books she covers, I can aver that this response was entirely predictable based on what the authors had written. So why does Shaw attempt to mislead her readers?

The false implication that the authors she’s reviewing support torture isn’t the only central premise of Shaw’s essay that’s simply wrong; if these psychologists really are trying to take power, as she claims, that’s news to them. Haidt and Pinker begin their rebuttal by pointing out that “Shaw can cite no psychologist who claims special authority or ‘superior wisdom’ on moral matters” (82). Every one of them, with a single exception, in fact includes an explanation of what separates the two endeavors—describing human morality on the one hand, and prescribing values or behaviors on the other—in the very books Shaw professes to find so alarming. The lone exception, Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, author of Just Babies: The Origins of Good and Evil, wrote to Haidt and Pinker, “The fact that one cannot derive morality from psychological research is so screamingly obvious that I never thought to explicitly write it down” (82).

Yet Shaw insists all of these authors commit the fallacy of moving from is to ought; you have to wonder if she even read the books she’s supposed to be reviewing—beyond mining them for damning quotes anyway. And didn’t any of the editors at The New York Review think to check some of her basic claims? Or were they simply hoping to bank on the publication of what amounts to controversy porn? (Think of the dilemma faced by the authors: do you respond and draw more attention to the piece, or do you ignore it and let some portion of the readership come away with a wildly mistaken impression?)

Haidt and Pinker do a fine job of calling out most of Shaw’s biggest mistakes and mischaracterizations. But I want to draw attention to two more instances of her falling short of any reasonable standard of scholarship, because each one reveals something important about the beliefs Shaw uses as her own moral compass. The authors under review situate their findings on human morality in a larger framework of theories about human evolution. Shaw characterizes this framework as “an unverifiable and unfalsifiable story about evolutionary psychology” (38). Shaw has evidently attended the Ken Ham school of evolutionary biology, which preaches that science can only concern itself with phenomena occurring right before our eyes in a lab. The reality is that, while testing adaptationist theories is a complicated endeavor, there are usually at least two ways to falsify them. You can show that the trait or behavior in question is absent in many cultures, or you can show that it emerges late in life after some sort of deliberate training. One of the books Shaw is supposedly reviewing, Bloom’s Just Babies, focuses specifically on research demonstrating that many of our common moral intuitions emerge when we’re babies, in our first year of life, with no deliberate training whatsoever.

Bloom comes in for some more targeted, if off-hand, criticism near the conclusion of Shaw’s essay for an article he wrote to challenge the increasingly popular sentiment that we can solve our problems as a society by encouraging everyone to be more empathetic. Empathy, Bloom points out, is a finite resource; we’re simply not capable of feeling for every single one of the millions of individuals in need of care throughout the world. So we need to offer that care based on principle, not feeling. Shaw avoids any discussion of her own beliefs about morality in her essay, but from the nature of her mischaracterization of Bloom’s argument we can start to get a sense of the ideology informing her prejudices. She insists that when Paul Bloom, in his own Atlantic article, “The Dark Side of Empathy,” warns us that empathy for people who are seen as victims may be associated with violent, punitive tendencies toward those in authority, we should be wary of extrapolating from his psychological claims a prescription for what should and should not be valued, or inferring that we need a moral corrective to a culture suffering from a supposed excess of empathic feelings. (40-1)

The “supposed excess of empathic feelings” isn’t the only laughable distortion people who actually read Bloom’s essay will catch out; the actual examples he cites of when empathy for victims leads to “violent, punitive tendencies” include Donald Trump and Ann Coulter stoking outrage against undocumented immigrants by telling stories of the crimes a few of them commit. This misrepresentation raises an important question: why would Shaw want to mislead her readers into believing Bloom’s intention is to protect those in authority? This brings us to the McCathyesque part of Shaw’s attack ad.

The sections of the essay drawing a web of guilt connecting the two psychologists who helped develop torture methods for the CIA to all the authors she’d have us believe are complicit focus mainly on Martin Seligman, whose theory of learned helplessness formed the basis of the CIA’s approach to harsh interrogation. Seligman is the founder of a subfield called Positive Psychology, which he developed as a counterbalance to what he perceived as an almost exclusive focus on all that can go wrong with human thinking, feeling, and behaving. His Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania has received $31 million in recent years from the Department of Defense—a smoking gun by Shaw’s lights. And Seligman even admits that on several occasions he met with those two psychologists who participated in the torture program. The other authors Shaw writes about have in turn worked with Seligman on a variety of projects. Haidt even wrote a book on Positive Psychology called The Happiness Hypothesis.

In Shaw’s view, learned helplessness theory is a potentially dangerous tool being wielded by a bunch of mad scientists and government officials corrupted by financial incentives and a lust for military dominance. To her mind, the notion that Seligman could simply want to help soldiers cope with the stresses of combat is all but impossible to even entertain. In this and every other instance when Shaw attempts to mislead her readers, it’s to put the same sort of negative spin on the psychologists’ explicitly stated positions. If Bloom says empathy has a dark side, then all the authors in question are against empathy. If Haidt argues that resilience—the flipside of learned helplessness—is needed to counteract a culture of victimhood, then all of these authors are against efforts to combat sexism and racism on college campuses. And, as we’ve seen, if these authors say we should question our moral intuitions, it’s because they want to be able to get away with crimes like torture. “Expertise in teaching people to override their moral intuitions is only a moral good if it serves good ends,” Shaw herself writes. “Those ends,” she goes on, “should be determined by rigorous moral deliberation” (40). Since this is precisely what the authors she’s criticizing say in their books, we’re left wondering what her real problem with them might be.

In her reply to Haidt and Pinker’s letter, Shaw suggests her aim for the essay was to encourage people to more closely scrutinize the “doctrines of Positive Psychology” and the central principles underlying psychological theories about human morality. I was curious to see how she’d respond to being called out for mistakenly stating that the psychologists were claiming moral authority and that they were given to using their research to defend the use of torture. Her main response is to repeat the central aspects of her rather flimsy case against Seligman. But then she does something truly remarkable; she doesn’t deny using guilt by imaginability—she defends it.

Pinker and Haidt say they prefer reality to imagination, but imagination is the capacity that allows us to take responsibility, insofar as it is ever possible, for the ends for which our work will be used and the consequences that it will have in the world. Such imagination is a moral and intellectual virtue that clearly needs to be cultivated. (85)

So, regardless of what the individual psychologists themselves explicitly say about torture, for instance, as long as they’re equipping other people with the conceptual tools to justify torture, they’re still at least somewhat complicit. This was the line that first made me realize Shaw’s essay was something other than a philosopher munching on sour grapes.

Shaw’s approach to connecting each of the individual authors to Seligman and then through him to the torture program is about as sophisticated, and about as credible, as any narrative concocted by your average online conspiracy theorist. But she believes that these connections are important and meaningful, a belief, I suspect, that derives from her own philosophy. Advocates of this philosophy, commonly referred to as postmodernismor poststructuralism, posit that our culture is governed by a dominant ideology that serves to protect and perpetuate the societal status quo, especially with regard to what are referred to as hegemonic relationships—men over women, whites over other ethnicities, heterosexuals over homosexuals. This dominant ideology finds expression in, while at the same time propagating itself through, cultural practices ranging from linguistic expressions to the creation of art to the conducting of scientific experiments.

Inspired by figures like Louis Althusser and Michel Foucault, postmodern scholars reject many of the central principles of humanism, including its emphasis on the role of rational discourse in driving societal progress. This is because the processes of reasoning and research that go into producing knowledge can never be fully disentangled from the exercise of power, or so it is argued. We experience the world through the medium of culture, and our culture distorts reality in a way that makes hierarchies seem both natural and inevitable. So, according to postmodernists, not only does science fail to create true knowledge of the natural world and its inhabitants, but the ideas it generates must also be scrutinized to identify their hidden political implications.

What such postmodern textual analyses look like in practice is described in sociologist Ullica Segerstrale’s book, Defenders of the Truth: The Sociobiology Debate. Segerstrale observed that postmodern critics of evolutionary psychology (which was more commonly called sociobiology in the late 90s), were outraged by what they presumed were the political implications of the theories, not by what evolutionary psychologists actually wrote. She explains,

In their analysis of their targets’ texts, the critics used a method I call moral reading. The basic idea behind moral reading was to imagine the worst possible political consequences of a scientific claim. In this way, maximum guilt might be attributed to the perpetrator of this claim. (206)

This is similar to the type of imagination Shaw faults psychologists today for insufficiently exercising. For the postmodernists, the sum total of our cultural knowledge is what sustains all the varieties of oppression and injustice that exist in our society, so unless an author explicitly decries oppression or injustice he’ll likely be held under suspicion. Five of the six books Shaw subjects to her moral reading were written by white males. The sixth was written by a male and a female, both white. The people the CIA tortured were not white. So you might imagine white psychologists telling everyone not to listen to their conscience to make it easier for them reap the benefits of a history of colonization. Of course, I could be completely wrong here; maybe this scenario isn’t what was playing out in Shaw’s imagination at all. But that’s the problem—there are few limits to what any of us can imagine, especially when it comes to people we disagree with on hot-button issues.

Postmodernism began in English departments back in the ‘60s where it was originally developed as an approach to analyzing literature. From there, it spread to several other branches of the humanities and is now making inroads into the social sciences. Cultural anthropology was the first field to be mostly overtaken. You can see precursors to Shaw’s rhetorical approach in attacks leveled against sociobiologists like E.O. Wilson and Napoleon Chagnon by postmodern anthropologists like Marshall Sahlins. In a review published in 2001, also in The New York Review of Books, Sahlins writes,

The ‘60s were the longest decade of the 20th century, and Vietnam was the longest war. In the West, the war prolonged itself in arrogant perceptions of the weaker peoples as instrumental means of the global projects of the stronger. In the human sciences, the war persists in an obsessive search for power in every nook and cranny of our society and history, and an equally strong postmodern urge to “deconstruct” it. For his part, Chagnon writes popular textbooks that describe his ethnography among the Yanomami in the 1960s in terms of gaining control over people.

Demonstrating his own power has been not only a necessary condition of Chagnon’s fieldwork, but a main technique of investigation.

The first thing to note is that Sahlin’s characterization of Chagnon’s books as narratives of “gaining control over people” is just plain silly; Chagnon was more often than not at the mercy of the Yanomamö. The second is that, just as anyone who’s actually read the books by Haidt, Pinker, Greene, and Bloom will be shocked by Shaw’s claim that their writing somehow bolsters the case for torture, anyone familiar with Chagnon’s studies of the Yanomamö will likely wonder what the hell they have to do with Vietnam, a war that to my knowledge he never expressed an opinion of in writing.

However, according to postmodern logic—or we might say postmodern morality—Chagnon’s observation that the Yanomamö were often violent, along with his espousal of a theory that holds such violence to have been common among preindustrial societies, leads inexorably to the conclusion that he wants us all to believe violence is part of our fixed nature as humans. Through the lens of postmodernism, Chagnon’s work is complicit in making people believe working for peace is futile because violence is inevitable. Chagnon may counter that he believes violence is likely to occur only in certain circumstances, and that by learning more about what conditions lead to conflict we can better equip ourselves to prevent it. But that doesn’t change the fact that society needs high-profile figures to bring before our modern academic version of the inquisition, so that all the other white men lording it over the rest of the world will see what happens to anyone who deviates from right (actually far-left) thinking.

Ideas really do have consequences of course, some of which will be unforeseen. The place where an idea ends up may even be repugnant to its originator. But the notion that we can settle foreign policy disputes, eradicate racism, end gender inequality, and bring about world peace simply by demonizing artists and scholars whose work goes against our favored party line, scholars and artists who maybe can’t be shown to support these evils and injustices directly but can certainly be imagined to be doing so in some abstract and indirect way—well, that strikes me as far-fetched. It also strikes me as dangerously misguided, since it’s not like scholars, or anyone else, ever needed any extra encouragement to imagine people who disagree with them being guilty of some grave moral offense. We’re naturally tempted to do that as it is.

Part of becoming a good scholar—part of becoming a grownup—is learning to live with people whose beliefs are different from yours, and to treat them fairly. Unless a particular scholar is openly and explicitly advocating torture, ascribing such an agenda to her is either irresponsible, if we’re unwittingly misrepresenting her, or dishonest, if we’re doing so knowingly. Arguments from imagined adverse consequences can go both ways. We could, for instance, easily write articles suggesting that Shaw is a Stalinist, or that she advocates prosecuting perpetrators of what members of the far left deem to be thought crimes. What about the consequences of encouraging suspicion of science in an age of widespread denial of climate change? Postmodern identity politics is this moment posing a threat to free speech on college campuses. And the tactics of postmodern activists begin and end with the stoking of moral outrage, so we could easily make a case that the activists are deliberately trying to instigate witch hunts. With each baseless accusation and counter-accusation, though, we’re getting farther and farther away from any meaningful inquiry, forestalling any substantive debate, and hamstringing any real moral or political progress.

Many people try to square the circle, arguing that postmodernism isn’t inherently antithetical to science, and that the supposed insights derived from postmodern scholarship ought to be assimilated somehow into science. When Thomas Huxley, the physician and biologist known as Darwin’s bulldog, said that science “commits suicide when it adopts a creed,” he was pointing out that by adhering to an ideology you’re taking its tenets for granted. Science, despite many critics’ desperate proclamations to the contrary, is not itself an ideology; science is an epistemology, a set of principles and methods for investigating nature and arriving at truths about the world. Even the most well-established of these truths, however, is considered provisional, open to potential revision or outright rejection as the methods, technologies, and theories that form the foundation of this collective endeavor advance over the generations.

In her essay, Shaw cites the results of a project attempting to replicate the findings of several seminal experiments in social psychology, counting the surprisingly low success rate as further cause for skepticism of the field. What she fails to appreciate here is that the replication project is being done by a group of scientists who are psychologists themselves, because they’re committed to honing their techniques for studying the human mind. I would imagine if Shaw’s postmodernist precursors had shared a similar commitment to assessing the reliability of their research methods, such as they are, and weighing the validity of their core tenets, then the ideology would have long since fallen out of fashion by the time she was taking up a pen to write about how scary psychologists are.

The point Shaw's missing here is that it’s precisely this constant quest to check and recheck the evidence, refine and further refine the methods, test and retest the theories, that makes science, if not a source of superior wisdom, then still the most reliable approach to answering questions about who we are, what our place is in the universe, and what habits and policies will give us, as individuals and as citizens, the best chance to thrive and flourish. As Saul Perlmutter, one of the discoverers of dark energy, has said, “Science is an ongoing race between our inventing ways to fool ourselves, and our inventing ways to avoid fooling ourselves.” Shaw may be right that no experimental result could ever fully settle a moral controversy, but experimental results are often not just relevant to our philosophical deliberations but critical to keeping those deliberations firmly grounded in reality.

Popular relevant posts:

JUST ANOTHER PIECE OF SLEAZE: THE REAL LESSON OF ROBERT BOROFSKY'S "FIERCE CONTROVERSY"

THE IDIOCY OF OUTRAGE: SAM HARRIS'S RUN-INS WITH BEN AFFLECK AND NOAM CHOMSKY

(My essay on Greene’s book)

LAB FLIES: JOSHUA GREENE’S MORAL TRIBES AND THE CONTAMINATION OF WALTER WHITE

(My essay on Pinker’s book)

(My essay on Haidt’s book)

THE ENLIGHTENED HYPOCRISY OF JONATHAN HAIDT'S RIGHTEOUS MIND

How Violent Fiction Works: Rohan Wilson’s “The Roving Party” and James Wood’s Sanguinary Sublime from Conrad to McCarthy

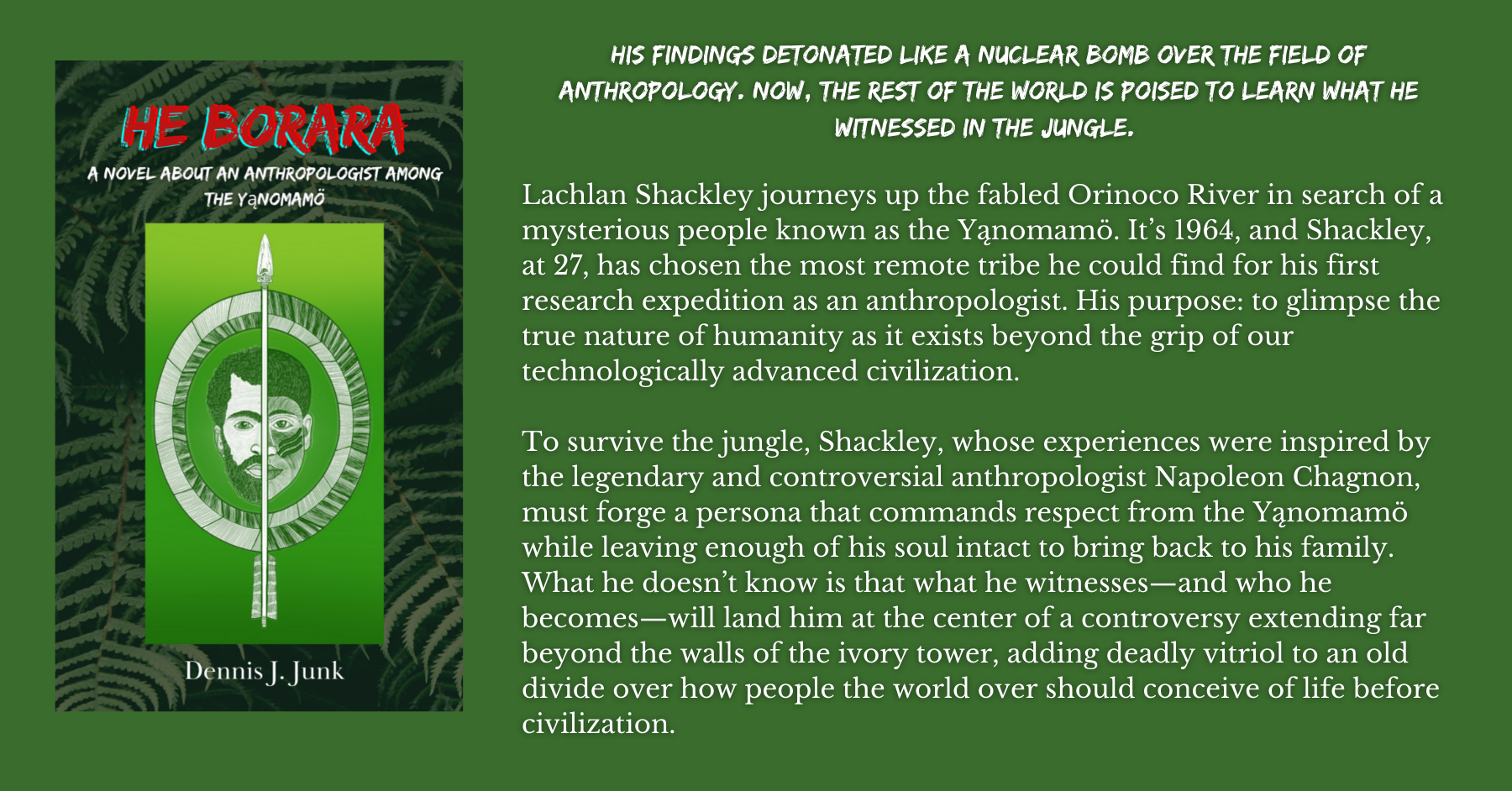

James Wood criticized Cormac McCathy’s “No Country for Old Men” for being too trapped by its own genre tropes. Wood has a strikingly keen eye for literary registers, but he’s missing something crucial in his analysis of McCarthy’s work. Rohan Wilson’s “The Roving Party” works on some of the same principles as McCarthy’s work, and it shows that the authors’ visions extend far beyond the pages of any book.

Any acclaimed novel of violence must be cause for alarm to anyone who believes stories encourage the behaviors depicted in them or contaminate the minds of readers with the attitudes of the characters. “I always read the book as an allegory, as a disguised philosophical argument,” writes David Shields in his widely celebrated manifesto Reality Hunger. Suspicious of any such disguised effort at persuasion, Shields bemoans the continuing popularity of traditional novels and agitates on behalf of a revolutionary new form of writing, a type of collage that is neither marked as fiction nor claimed as truth but functions rather as a happy hybrid—or, depending on your tastes, a careless mess—and is in any case completely lacking in narrative structure. This is because to him giving narrative structure to a piece of writing is itself a rhetorical move. “I always try to read form as content, style as meaning,” Shields writes. “The book is always, in some sense, stutteringly, about its own language” (197).

As arcane as Shields’s approach to reading may sound, his attempt to find some underlying message in every novel resonates with the preoccupations popular among academic literary critics. But what would it mean if novels really were primarily concerned with their own language, as so many students in college literature courses are taught? What if there really were some higher-order meaning we absorbed unconsciously through reading, even as we went about distracting ourselves with the details of description, character, and plot? Might a novel like Heart of Darkness, instead of being about Marlowe’s growing awareness of Kurtz’s descent into inhuman barbarity, really be about something that at first seems merely contextual and incidental, like the darkness—the evil—of sub-Saharan Africa and its inhabitants? Might there be a subtle prompt to regard Kurtz’s transformation as some breed of enlightenment, a fatal lesson encapsulated and propagated by Conrad’s fussy and beautifully tantalizing prose, as if the author were wielding the English language like the fastenings of a yoke over the entire continent?

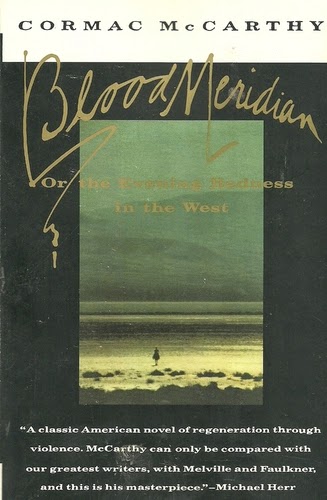

Novels like Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and, more recently, Rohan Wilson’s The Roving Party, take place amid a transition from tribal societies to industrial civilization similar to the one occurring in Conrad’s Congo. Is it in this seeming backdrop that we should seek the true meaning of these tales of violence? Both McCarthy’s and Wilson’s novels, it must be noted, represent conspicuous efforts at undermining the sanitized and Manichean myths that arose to justify the displacement and mass killing of indigenous peoples by Europeans as they spread over the far-flung regions of the globe. The white men hunting “Indians” for the bounties on their scalps in Blood Meridian are as beastly and bloodthirsty as the savages peopling the most lurid colonial propaganda, just as the Europeans making up Wilson’s roving party are only distinguishable by the relative degrees of their moral degradation, all of them, including the protagonist, moving in the shadow of their chief quarry, a native Tasmanian chief.

If these novels are about their own language, their form comprising their true content, all in the service of some allegory or argument, then what pleasure would anyone get from them, suggesting as they do that to partake of the fruit of civilization is to become complicit in the original sin of the massacre that made way for it? “There is no document of civilization,” Walter Benjamin wrote, “that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” It could be that to read these novels is to undergo a sort of rite of expiation, similar to the ritual reenactment of the crucifixion performed by Christians in the lead up to Easter. Alternatively, the real argument hidden in these stories may be still more insidious; what if they’re making the case that violence is both eternal and unavoidable, that it is in our nature to relish it, so there’s no more point in resisting the urge personally than in trying to bring about reform politically?

Shields intimates that the reason we enjoy stories is that they warrant our complacency when he writes, “To ‘tell a story well’ is to make what one writes resemble the schemes people are used to—in other words, their ready-made idea of reality” (200). Just as we take pleasure in arguments for what we already believe, Shields maintains (explicitly) that we delight in stories that depict familiar scenes and resolve in ways compatible with our convictions. And this equating of the pleasure we take in reading with the pleasure we take in having our beliefs reaffirmed is another practice nearly universal among literary critics. Sophisticated readers know better than to conflate the ideas professed by villainous characters like the judge in Blood Meridian with those of the author, but, as one prominent critic complains,

there is often the disquieting sense that McCarthy’s fiction puts certain fond American myths under pressure merely to replace them with one vaster myth—eternal violence, or [Harold] Bloom’s “universal tragedy of blood.” McCarthy’s fiction seems to say, repeatedly, that this is how it has been and how it always will be.

What’s interesting about this interpretation is that it doesn’t come from anyone normally associated with Shields’s school of thought on literature. Indeed, its author, James Wood, is something of a scourge to postmodern scholars of Shields’s ilk.

Wood takes McCarthy to task for his alleged narrative dissemination of the myth of eternal violence in a 2005 New Yorker piece, Red Planet: The Sanguinary Sublime of Cormac McCarthy, a review of his then latest novel No Country for Old Men. Wood too, it turns out, hungers for reality in his novels, and he faults McCarthy’s book for substituting psychological profundity with the pabulum of standard plot devices. He insists that

the book gestures not toward any recognizable reality but merely toward the narrative codes already established by pulp thrillers and action films. The story is itself cinematically familiar. It is 1980, and a young man, Llewelyn Moss, is out antelope hunting in the Texas desert. He stumbles upon several bodies, three trucks, and a case full of money. He takes the money. We know that he is now a marked man; indeed, a killer named Anton Chigurh—it is he who opens the book by strangling the deputy—is on his trail.

Because McCarthy relies on the tropes of a familiar genre to convey his meaning, Wood suggests, that meaning can only apply to the hermetic universe imagined by that genre. In other words, any meaning conveyed in No Country for Old Men is rendered null in transit to the real world.

When Chigurh tells the blameless Carla Jean that “the shape of your path was visible from the beginning,” most readers, tutored in the rhetoric of pulp, will write it off as so much genre guff. But there is a way in which Chigurh is right: the thriller form knew all along that this was her end.

The acuity of Wood’s perception when it comes to the intricacies of literary language is often staggering, and his grasp of how diction and vocabulary provide clues to the narrator’s character and state of mind is equally prodigious. But, in this dismissal of Chigurh as a mere plot contrivance, as in his estimation of No Country for Old Men in general as a “morally empty book,” Wood is quite simply, quite startlingly, mistaken. And we might even say that the critical form knew all along that he would make this mistake.

When Chigurh tells Carla Jean her path was visible, he’s not voicing any hardboiled fatalism, as Wood assumes; he’s pointing out that her predicament came about as a result of a decision her husband Llewelyn Moss made with full knowledge of the promised consequences. And we have to ask, could Wood really have known, before Chigurh showed up at the Moss residence, that Carla Jean would be made to pay for her husband’s defiance? It’s easy enough to point out superficial similarities to genre conventions in the novel (many of which it turns inside-out), but it doesn’t follow that anyone who notices them will be able to foretell how the book will end. Wood, despite his reservations, admits that No Country for Old Men is “very gripping.” But how could it be if the end were so predictable? And, if it were truly so morally empty, why would Wood care how it was going to end enough to be gripped? Indeed, it is in the realm of the characters’ moral natures that Wood is the most blinded by his reliance on critical convention. He argues,

Lewelyn Moss, the hunted, ought not to resemble Anton Chigurh, the hunter, but the flattening effect of the plot makes them essentially indistinguishable. The reader, of course, sides with the hunted. But both have been made unfree by the fake determinism of the thriller.

How could the two men’s fates be determined by the genre if in a good many thrillers the good guy, the hunted, prevails?

One glaring omission in Wood’s analysis is that Moss initially escapes undetected with the drug money he discovers at the scene of the shootout he happens upon while hunting, but he is then tormented by his conscience until he decides to return to the trucks with a jug of water for a dying man who begged him for a drink. “I’m fixin to go do somethin dumbern hell but I’m goin anyways,” he says to Carla Jean when she asks what he’s doing. “If I don’t come back tell Mother I love her” (24). Llewelyn, throughout the ensuing chase, is thus being punished for doing the right thing, an injustice that unsettles readers to the point where we can’t look away—we’re gripped—until we’re assured that he ultimately defeats the agents of that injustice. While Moss risks his life to give a man a drink, Chigurh, as Wood points out, is first seen killing a cop. Moreover, it’s hard to imagine Moss showing up to murder an innocent woman to make good on an ultimatum he’d presented to a man who had already been killed in the interim—as Chigurh does in the scene when he explains to Carla Jean that she’s to be killed because Llewelyn made the wrong choice.

Chigurh is in fact strangely principled, in a morally inverted sort of way, but the claim that he’s indistinguishable from Moss bespeaks a failure of attention completely at odds with the uncannily keen-eyed reading we’ve come to expect from Wood. When he revisits McCarthy’s writing in a review of the 2006 post-apocalyptic novel The Road, collected in the book The Fun Stuff, Wood is once again impressed by McCarthy’s “remarkable effects” but thoroughly baffled by “the matter of his meanings” (61). The novel takes us on a journey south to the sea with a father and his son as they scrounge desperately for food in abandoned houses along the way. Wood credits McCarthy for not substituting allegory for the answer to “a simpler question, more taxing to the imagination and far closer to the primary business of fiction making: what would this world without people look like, feel like?” But then he unaccountably struggles to sift out the novel’s hidden philosophical message. He writes,

A post-apocalyptic vision cannot but provoke dilemmas of theodicy, of the justice of fate; and a lament for the Deus absconditus is both implicit in McCarthy’s imagery—the fine simile of the sun that circles the earth “like a grieving mother with a lamp”—and explicit in his dialogue. Early in the book, the father looks at his son and thinks: “If he is not the word of God God never spoke.” There are thieves and murderers and even cannibals on the loose, and the father and son encounter these fearsome envoys of evil every so often. The son needs to think of himself as “one of the good guys,” and his father assures him that this is the side they are indeed on. (62)

We’re left wondering, is there any way to answer the question of what a post-apocalypse would be like in a story that features starving people reduced to cannibalism without providing fodder for genre-leery critics on the lookout for characters they can reduce to mere “envoys of evil”?

As trenchant as Wood is regarding literary narration, and as erudite—or pedantic, depending on your tastes—as he is regarding theology, the author of the excellent book How Fiction Works can’t help but fall afoul of his own, and his discipline’s, thoroughgoing ignorance when it comes to how plots work, what keeps the moral heart of a story beating. The way Wood fails to account for the forest comprised of the trees he takes such thorough inventory of calls to mind a line of his own from a chapter in The Fun Stuff about Edmund Wilson, describing an uncharacteristic failure on part of this other preeminent critic:

Yet the lack of attention to detail, in a writer whose greatness rests supremely on his use of detail, the unwillingness to talk of fiction as if narrative were a special kind of aesthetic experience and not a reducible proposition… is rather scandalous. (72)

To his credit, though, Wood never writes about novels as if they were completely reducible to their propositions; he doesn’t share David Shields’s conviction that stories are nothing but allegories or disguised philosophical arguments. Indeed, few critics are as eloquent as Wood on the capacity of good narration to communicate the texture of experience in a way all literate people can recognize from their own lived existences.

But Wood isn’t interested in plot. He just doesn’t seem to like them. (There’s no mention of plot in either the table of contents or the index to How Fiction Works.) Worse, he shares Shields’s and other postmodern critics’ impulse to decode plots and their resolutions—though he also searches for ways to reconcile whatever moral he manages to pry from the story with its other elements. This is in fact one of the habits that tends to derail his reviews. Even after lauding The Road’s eschewal of easy allegory in place of the hard work of ground-up realism, Wood can’t help trying to decipher the end of the novel in the context of the religious struggle he sees taking place in it. He writes of the son’s survival,

The boy is indeed a kind of last God, who is “carrying the fire” of belief (the father and son used to speak of themselves, in a kind of familial shorthand, as people who were carrying the fire: it seems to be a version of being “the good guys”.) Since the breath of God passes from man to man, and God cannot die, this boy represents what will survive of humanity, and also points to how life will be rebuilt. (64)

This interpretation underlies Wood’s contemptuous attitude toward other reviewers who found the story uplifting, including Oprah, who used The Road as one of her book club selections. To Wood, the message rings false. He complains that

a paragraph of religious consolation at the end of such a novel is striking, and it throws the book off balance a little, precisely because theology has not seemed exactly central to the book’s inquiry. One has a persistent, uneasy sense that theodicy and the absent God have been merely exploited by the book, engaged with only lightly, without much pressure of interrogation. (64)

Inquiry? Interrogation? Whatever happened to “special kind of aesthetic experience”? Wood first places seemingly inconsequential aspects of the novel at the center of his efforts to read meaning into it, and then he faults the novel for not exploring these aspects at greater length. The more likely conclusion we might draw here is that Wood is simply and woefully mistaken in his interpretation of the book’s meaning. Indeed, Wood’s jump to theology, despite his insistence on its inescapability, is really quite arbitrary, one of countless themes a reader might possibly point to as indicative of the novel’s one true meaning.

Perhaps the problem here is the assumption that a story must have a meaning, some point that can be summed up in a single statement, for it to grip us. Getting beyond the issue of what statement the story is trying to make, we can ask what it is about the aesthetic experience of reading a novel that we find so compelling. For Wood, it’s clear the enjoyment comes from a sort of communion with the narrator, a felt connection forged by language, which effects an estrangement from his own mundane experiences by passing them through the lens of the character’s idiosyncratic vocabulary, phrasings, and metaphors. The sun dimly burning through an overcast sky looks much different after you’ve heard it compared to “a grieving mother with a lamp.” This pleasure in authorial communion and narrative immersion is commonly felt by the more sophisticated of literary readers. But what about less sophisticated readers? Many people who have a hard enough time simply understanding complex sentences, never mind discovering in them clues to the speaker’s personality, nevertheless become absorbed in narratives.

Developmental psychologists Karen Wynn and Paul Bloom, along with then graduate student Kiley Hamlin, serendipitously discovered a major clue to the mystery of why fictional stories engage humans’ intellectual and emotional faculties so powerfully while trying to determine at what age children begin to develop a moral sense. In a series of experiments conducted at the Yale Infant Cognition Center, Wynn and her team found that babies under a year old, even as young as three months, are easily induced to attribute agency to inanimate objects with nothing but a pair of crude eyes to suggest personhood. And, astonishingly, once agency is presumed, these infants begin attending to the behavior of the agents for evidence of their propensities toward being either helpfully social or selfishly aggressive—even when they themselves aren’t the ones to whom the behaviors are directed.

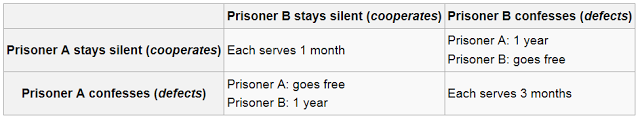

In one of the team’s most dramatic demonstrations, the infants watch puppet shows featuring what Bloom, in his book about the research program Just Babies, refers to as “morality plays” (30). Two rabbits respond to a tiger’s overture of rolling a ball toward them in different ways, one by rolling it back playfully, the other by snatching it up and running away with it. When the babies are offered a choice between the two rabbits after the play, they nearly always reach for the “good guy.” However, other versions of the experiment show that babies do favor aggressive rabbits over nice ones—provided that the victim is itself guilty of some previously witnessed act of selfishness or aggression. So the infants prefer cooperation over selfishness and punishment over complacency.

Wynn and Hamlin didn’t intend to explore the nature of our fascination with fiction, but even the most casual assessment of our most popular stories suggests their appeal to audiences depends on a distinction similar to the one made by the infants in these studies. Indeed, the most basic formula for storytelling could be stated: good guy struggles against bad guy. Our interest is automatically piqued once such a struggle is convincingly presented, and it doesn’t depend on any proposition that can be gleaned from the outcome.

We favor the good guy because his (or her) altruism triggers an emotional response—we like him. And our interest in the ongoing developments of the story—the plot—are both emotional and dynamic. This is what the aesthetic experience of narrative consists of.

The beauty in stories comes from the elevation we get from the experience of witnessing altruism, and the higher the cost to the altruist the more elevating the story. The symmetry of plots is the balance of justice. Stories meant to disturb readers disrupt that balance.The crudest stories pit good guys against bad guys. The more sophisticated stories feature what we hope are good characters struggling against temptations or circumstances that make being good difficult, or downright dangerous. In other words, at the heart of any story is a moral dilemma, a situation in which characters must decide who deserves what fate and what they’re willing to pay to ensure they get it. The specific details of that dilemma are what we recognize as the plot.

The most basic moral, lesson, proposition, or philosophical argument inherent in the experience of attending to a story derives then not from some arbitrary decision on the part of the storyteller but from an injunction encoded in our genome. At some point in human evolution, our ancestor’s survival began to depend on mutual cooperation among all the members of the tribe, and so to this day, and from a startlingly young age, we’re on the lookout for anyone who might be given to exploiting the cooperative norms of our group. Literary critics could charge that the appeal of the altruist is merely another theme we might at this particular moment in history want to elevate to the status of most fundamental aspect of narrative. But I would challenge anyone who believes some other theme, message, or dynamic is more crucial to our engagement with stories to subject their theory to the kind of tests the interplay of selfish and altruistic impulses routinely passes in the Yale studies. Do babies care about theodicy? Are Wynn et al.’s morality plays about their own language?

This isn’t to say that other themes or allegories never play a role in our appreciation of novels. But whatever role they do play is in every case ancillary to the emotional involvement we have with the moral dilemmas of the plot. 1984 and Animal Farm are clear examples of allegories—but their greatness as stories is attributable to the appeal of their characters and the convincing difficulty of their dilemmas. Without a good plot, no one would stick around for the lesson. If we didn’t first believe Winston Smith deserved to escape Room 101 and that Boxer deserved a better fate than the knackery, we’d never subsequently be moved to contemplate the evils of totalitarianism. What makes these such powerful allegories is that, if you subtracted the political message, they’d still be great stories because they engage our moral emotions.

What makes violence so compelling in fiction then is probably not that it sublimates our own violent urges, or that it justifies any civilization’s past crimes; violence simply ups the stakes for the moral dilemmas faced by the characters. The moment by moment drama in The Road, for instance, has nothing to do with whether anyone continues to believe in God. The drama comes from the father and son’s struggles to resist having to succumb to theft and cannibalism to survive. That’s the most obvious theme recurring throughout the novel. And you get the sense that were it not for the boy’s constant pleas for reassurance that they would never kill and eat anyone—the ultimate act of selfish aggression—and that they would never resort to bullying and stealing, the father quite likely would have made use of such expedients. The fire that they’re carrying is not the light of God; it’s the spark of humanity, the refusal to forfeit their human decency. (Wood doesn't catch that the fire was handed off from Sheriff Bell's father at the end of No Country.) The boy may very well be a redeemer, in that he helps his father make it to the end of his life with a clear conscience, but unless you believe morality is exclusively the bailiwick of religion God’s role in the story is marginal at best.

What the critics given to dismissing plots as pointless fabrications fail to consider is that just as idiosyncratic language and simile estranges readers from their mundane existence so too the high-stakes dilemmas that make up plots can make us see our own choices in a different light, effecting their own breed of estrangement with regard to our moral perceptions and habits. In The Roving Party, set in the early nineteenth century, Black Bill, a native Tasmanian raised by a white family, joins a group of men led by a farmer named John Batman to hunt and kill other native Tasmanians and secure the territory for the colonials. The dilemmas Bill faces are like nothing most readers will ever encounter. But their difficulty is nonetheless universally understandable. In the following scene, Bill, who is also called the Vandemonian, along with a young boy and two native scouts, watches as Batman steps up to a wounded clansman in the aftermath of a raid on his people.

Batman considered the silent man secreted there in the hollow and thumbed back the hammers. He put one foot either side of the clansman’s outstretched legs and showed him the long void of those bores, standing thus prepared through a few creakings of the trees. The warrior was wide-eyed, looking to Bill and to the Dharugs.

The eruption raised the birds squealing from the branches. As the gunsmoke cleared the fellow slumped forward and spilled upon the soil a stream of arterial blood. The hollow behind was peppered with pieces of skull and other matter. John Batman snapped open the locks, cleaned out the pans with his cloth and mopped the blood off the barrels. He looked around at the rovers.

The boy was openmouthed, pale, and he stared at the ruination laid out there at his feet and stepped back as the blood ran near his rags. The Dharugs had by now turned away and did not look back. They began retracing their track through the rainforest, picking among the fallen trunks. But Black Bill alone among that party met Batman’s eye. He resettled his fowling piece across his back and spat on the ferns, watching Batman. Batman pulled out his rum, popped loose the cork, and drank. He held out the vessel to Bill. The Vandemonian looked at him. Then he turned to follow the Parramatta men out among the lemon myrtles and antique pines. (92)

If Rohan Wilson had wanted to expound on the evils of colonialism in Tasmania, he might have written about how Batman, a real figure from history, murdered several men he could easily have taken prisoner. But Wilson wanted to tell a story, and he knew that dilemmas like this one would grip our emotions. He likewise knew he didn’t have to explain that Bill, however much he disapproves of the murder, can’t afford to challenge his white benefactor in any less subtle manner than meeting his eyes and refusing his rum.

Unfortunately, Batman registers the subtle rebuke all too readily. Instead of killing a native lawman wounded in a later raid himself, Batman leaves the task to Bill, who this time isn’t allowed the option of silently disapproving. But the way Wilson describes Bill’s actions leaves no doubt in the reader’s mind about his feelings, and those feelings have important consequences for how we feel about the character.

Black Bill removed his hat. He worked back the heavy cocks of both barrels and they settled with a dull clunk. Taralta clutched at his swaddled chest and looked Bill in the eyes, as wordless as ground stone. Bill brought up the massive gun and steadied the barrels across his forearm as his broken fingers could not take the weight. The sight of those octagonal bores levelled on him caused the lawman to huddle down behind his hands and cry out, and Bill steadied the gun but there was no clear shot he might take. He waited.

See now, he said. Move your hands.

The lawman crabbed away over the dirt, still with his arms upraised, and Bill followed him and kicked him in the bandaged ribs and kicked at his arms.

menenger, Bill said, menenger.

The lawman curled up more tightly. Bill brought the heel of his boot to bear on the wounded man but he kicked in vain while Taralta folded his arms ever tighter around his head.

Black Bill lowered the gun. Wattlebirds made their yac-a-yac coughs in the bush behind and he gazed at the blue hills to the south and the snow clouds forming above them. When Bill looked again at the lawman he was watching through his hands, dirt and ash stuck in the cords of his ochred hair. Bill brought the gun up, balanced it across his arm again and tucked the butt into his shoulder. Then he fired into the lawman’s head.

The almighty concussion rattled the wind in his chest and the gun bucked from his grip and fell. He turned away, holding his shoulder. Blood had spattered his face, his arms, the front of his shirt. For a time he would not look at the body of the lawman where it lay near the fire. He rubbed at the bruising on his shoulder; watched storms amass around the southern peaks. After a while he turned to survey the slaughter he had wrought.

One of the lawman’s arms was gone at the elbow and the teeth seated in the jawbone could be seen through the cheek. There was flesh blown every place. He picked up the Manton gun. The locks were soiled and he fingered out the grime, and then with the corner of his coat cleaned the pan and blew into the latchworks. He brought the weapon up to eye level and peered along its sights for barrel warps or any misalignment then, content, slung the leather on his shoulder. Without a rearward glance he stalked off, his hat replaced, his boots slipping in the blood. Smoke from the fire blew around him in a snarl raised on the wind and dispersed again on the same. (102-4)

Depending on their particular ideological bent, critics may charge that a scene like this simply promotes the type of violence it depicts, or that it encourages a negative view of native Tasmanians—or indigenous peoples generally—as of such weak moral fiber that they can be made to turn against their own countrymen. And pointing out that the aspect of the scene that captures our attention is the process, the experience, of witnessing Bill’s struggle to resolve his dilemma would do little to ease their worries; after all, even if the message is ancillary, its influence could still be pernicious.

The reason that critics applying their favored political theories to their analyses of fiction so often stray into the realm of the absurd is that the only readers who experience stories the same way as they do will be the ones who share the same ideological preoccupations. You can turn any novel into a Rorschach, pulling out disparate shapes and elements to blur into some devious message. But any reader approaching the writing without your political theories or your critical approach will likely come away with a much more basic and obvious lesson. Black Bill’s dilemma is that he has to kill many of his fellow Tasmanians if he wants to continue living as part of a community of whites. If readers take on his attitude toward killing as it’s demonstrated in the scene when he kills Taralta, they’ll be more reluctant to do it, not less. Bill clearly loathes what he’s forced to do. And if any race comes out looking bad it’s the whites, since they’re the ones whose culture forces Bill to choose between his family’s well-being and the dictates of his conscience.

Readers likely have little awareness of being influenced by the overarching themes in their favorite stories, but upon reflection the meaning of those themes is usually pretty obvious. Recent research into how reading the Harry Potter books has impacted young people’s political views, for instance, shows that fans of the series are more accepting of out-groups, more tolerant, less predisposed to authoritarianism, more supporting of equality, and more opposed to violence and torture. Anthony Gierzynsky, the author of the study, points out, “As Harry Potter fans will have noted, these are major themes repeated throughout the series.” The messages that reach readers are the conspicuous ones, not the supposedly hidden ones critics pride themselves on being able to suss out.

It’s an interesting question just how wicked stories could persuade us to be, relying as they do on our instinctual moral sense. Fans could perhaps be biased toward evil by themes about the threat posed by some out-group, or the debased nature of the lower orders, or nonbelievers in the accepted deities—since the salience of these concepts likewise seems to be inborn. But stories told from the perspective of someone belonging to the persecuted group could provide an antidote. At any rate, there’s a solid case to be made that novels have helped the moral of arc of history bend toward greater justice and compassion.

Even a novel with violence as pervasive and chaotic as it is in Blood Meridian sets up a moral gradient for the characters to occupy—though finding where the judge fits is a quite complicated endeavor—and the one with the most qualms about killing happens to be the protagonist, referred to simply as the kid. “You alone were mutinous,” the judge says to him. “You alone reserved in your soul some corner of clemency for the heathen” (299). The kid’s character is revealed much the way Black Bill’s is in The Roving Party, as readers witness him working through high-stakes dilemmas. After drawing arrows to determine who in the band of scalp hunters will stay behind to kill some of their wounded (to prevent a worse fate at the hands of the men pursuing them), the kid finds himself tasked with euthanizing a man who would otherwise survive.

You wont thank me if I let you off, he said.

Do it then you son of a bitch.

The kid sat. A light wind was blowing out of the north and some doves had begun to call in the thicket of greasewood behind them.

If you want me just to leave you I will.

Shelby didnt answer

He pushed a furrow in the sand with the heel of his boot. You’ll have to say.

Will you leave me a gun?

You know I can’t leave you no gun.

You’re no better than him. Are you?

The kid didn’t answer. (208)

That “him” is ambiguous; it could either be Glanton, the leader of the gang whose orders the kid is ignoring, or the judge, who engages him throughout the later parts of the novel in a debate about the necessity of violence in history. We know by now that the kid really is better than the judge—at least in the sense that Shelby means. And the kid handles the dilemma, as best he can, by hiding Shelby in some bushes and leaving him with a canteen of water.

These three passages from The Roving Party and Blood Meridian reveal as well something about the language commonly used by authors of violent novels going back to Conrad (perhaps as far back as Tolstoy). Faced with the choice of killing a man—or of standing idly by and allowing him to be killed—the characters hesitate, and the space of their hesitation is filled with details like the type of birdsong that can be heard. This style of “dirty realism,” a turning away from abstraction, away even from thought, to focus intensely on physical objects and the natural world, frustrates critics like James Wood because they prefer their prose to register the characters’ meanderings of mind in the way that only written language can. Writing about No Country for Old Men, Wood complains about all the labeling and descriptions of weapons and vehicles to the exclusion of thought and emotion.

Here is Hemingway’s influence, so popular in male American fiction, of both the pulpy and the highbrow kind. It recalls the language of “A Farewell to Arms”: “He looked very dead. It was raining. I had liked him as well as anyone I ever knew.” What appears to be thought is in fact suppressed thought, the mere ratification of male taciturnity. The attempt to stifle sentimentality—“He looked very dead”—itself comes to seem a sentimental mannerism. McCarthy has never been much interested in consciousness and once declared that as far as he was concerned Henry James wasn’t literature. Alas, his new book, with its gleaming equipment of death, its mindless men and absent (but appropriately sentimentalized) women, its rigid, impacted prose, and its meaningless story, is perhaps the logical result of a literary hostility to Mind.

Here again Wood is relaxing his otherwise razor-keen capacity for gleaning insights from language and relying instead on the anemic conventions of literary criticism—a discipline obsessed with the enactment of gender roles. (I’m sure Suzanne Collins would be amused by this idea of masculine taciturnity.) But Wood is right to recognize the natural tension between a literature of action and a literature of mind. Imagine how much the impact of Black Bill’s struggle with the necessity of killing Taralta would be blunted if we were privy to his thoughts, all of which are implicit in the scene as Wilson has rendered it anyway.

Fascinatingly, though, it seems that Wood eventually realized the actual purpose of this kind of evasive prose—and it was Cormac McCarthy he learned it from. As much as Wood lusts after some leap into theological lucubration as characters reflect on the lessons of the post-apocalypse or the meanings of violence, the psychological reality is that it is often in the midst of violence or when confronted with imminent death that people are least given to introspection. As Wood explains in writing about the prose style of The Road,

McCarthy writes at one point that the father could not tell the son about life before the apocalypse: “He could not construct for the child’s pleasure the world he’d lost without constructing the loss as well and thought perhaps the child had known this better than he.” It is the same for the book’s prose style: just as the father cannot construct a story for the boy without also constructing the loss, so the novelist cannot construct the loss without the ghost of the departed fullness, the world as it once was. (55)

The rituals of weapon reloading, car repair, and wound wrapping that Wood finds so offputtingly affected in No Country for Old Men are precisely the kind of practicalities people would try to engage their minds with in the aftermath of violence to avoid facing the reality. But this linguistic and attentional coping strategy is not without moral implications of its own.

In the opening of The Roving Party, Black Bill receives a visit from some of the very clansmen he’s been asked by John Batman to hunt. The headman of the group is a formidable warrior named Manalargena (another real historical figure), who is said to have magical powers. He has come to recruit Bill to help in fighting against the whites, unaware of Bill’s already settled loyalties. When Bill refuses to come fight with Manalargena, the headman’s response is to tell a story about two brothers who live near a river where they catch plenty of crayfish, make fires, and sing songs. Then someone new arrives on the scene:

Hunter come to the river. He is hungry hunter you see. He want crayfish. He see them brother eating crayfish, singing song. He want crayfish too. He bring up spear. Here the headman made as if to raise something. He bring up that spear and he call out: I hungry, you give me that crayfish. He hold that spear and he call out. But them brother they scared you see. They scared and they run. They run and they change. They change to wallaby and they jump. Now they jump and jump and the hunter he follow them.

So hunter he change too. He run and he change to that wallaby and he jump. Now three wallaby jump near river. They eat grass. They forget crayfish. They eat grass and they drink water and they forget crayfish. Three wallaby near the river. Very big river. (7-8)

Bill initially dismisses the story, saying it makes no sense. Indeed, as a story, it’s terrible. The characters have no substance and the transformation seems morally irrelevant. The story is pure allegory. Interestingly, though, by the end of the novel, its meaning is perfectly clear to Bill. Taking on the roles of hunter and hunted leaves no room for songs, no place for what began the hunt in the first place, creating a life closer to that of animals than of humans. There are no more fires.

Wood counts three registers authors like Conrad and McCarthy—and we can add Wilson—use in their writing. The first is the dirty realism that conveys the characters’ unwillingness to reflect on their circumstances or on the state of their souls. The third is the lofty but oblique discourse on God’s presence or absence in a world of tragedy and carnage Wood finds so ineffectual. For most readers, though, it’s the second register that stands out. Here’s how Wood describes it:

Hard detail and a fine eye is combined with exquisite, gnarled, slightly antique (and even slightly clumsy or heavy) lyricism. It ought not to work, and sometimes it does not. But many of its effects are beautiful—and not only beautiful, but powerfully efficient as poetry. (59)

This description captures what’s both great and frustrating about the best and worst lines in these authors’ novels. But Wood takes the tradition for granted without asking why this haltingly graceful and heavy-handedly subtle language is so well-suited to these violent stories. The writers are compelled to use this kind of language by the very effects of the plot and setting that critics today so often fail to appreciate—though Wood does gesture toward it in the title of his essay on No Country for Old Men. The dream logic of song and simile that goes into the aesthetic experience of bearing witness to the characters sparsely peopling the starkly barren and darkly ominous landscapes of these novels carries within it the breath of the sublime.

In coming to care about characters whose fates unfold in the aftermath of civilization, or in regions where civilization has yet to take hold, places where bloody aggression and violent death are daily concerns and witnessed realities, we’re forced to adjust emotionally to the worlds they inhabit. Experiencing a single death brings a sense of tragedy, but coming to grips with a thousand deaths has a more curious effect. And it is this effect that the strange tangles of metaphorical prose both gesture toward and help to induce. The sheer immensity of the loss, the casual brushing away of so many bodies and the blotting out of so much unique consciousness, overstresses the capacity of any individual to comprehend it. The result is paradoxical, a fixation on the material objects still remaining, and a sliding off of one’s mind onto a plane of mental existence where the material has scarcely any reality at all because it has scarcely any significance at all. The move toward the sublime is a lifting up toward infinite abstraction, the most distant perspective ever possible on the universe, where every image is a symbol for some essence, where every embrace is a symbol for human connectedness, where every individual human is a symbol for humanity. This isn’t the abstraction of logic, the working out of implications about God or cosmic origins. It’s the abstraction of the dream or the religious experience, an encounter with the sacred and the eternal, a falling and fading away of the world of the material and the particular and the mundane.

The prevailing assumption among critics and readers alike is that fiction, especially literary fiction, attempts to represent some facet of life, so the nature of a given representation can be interpreted as a comment on whatever is being represented. But what if the representations, the correspondences between the fictional world and the nonfictional one, merely serve to make the story more convincing, more worthy of our precious attention? What if fiction isn’t meant to represent reality so much as to alter our perceptions of it? Critics can fault plots like the one in No Country for Old Men, and characters like Anton Chigurh, for having no counterparts outside the world of the story, mooting any comment about the real world the book may be trying to make. But what if the purpose of drawing readers into fictional worlds is to help them see their own worlds anew by giving them a taste of what it would be like to live a much different existence? Even the novels that hew more closely to the mundane, the unremarkable passage of time, are condensed versions of the characters’ lives, encouraging readers to take a broader perspective on their own. The criteria we should apply to our assessments of novels then would not be how well they represent reality and how accurate or laudable their commentaries are. We should instead judge novels by how effectively they pull us into the worlds they create for themselves and how differently we look at our own world in the wake of the experience. And since high-stakes moral dilemmas are the heart of stories we might wonder what effect the experience of witnessing them will have on our own lower-stakes lives.

Also read:

HUNGER GAME THEORY: Post-Apocalyptic Fiction and the Rebirth of Humanity

Life's White Machine: James Wood and What Doesn't Happen in Fiction

LET'S PLAY KILL YOUR BROTHER: FICTION AS A MORAL DILEMMA GAME

Science’s Difference Problem: Nicholas Wade’s Troublesome Inheritance and the Missing Moral Framework for Discussing the Biology of Behavior

Nicholas Wade went there. In his book “A Troublesome Inheritance,” he argues that not only is race a real, biological phenomenon, but one that has potentially important implications for our understanding of the fates of different peoples. Is it possible to even discuss such things without being justifiably labeled a racist? More importantly, if biological differences do show up in the research, how can we discuss them without being grossly immoral?

No sooner had Nicholas Wade’s new book become available for free two-day shipping than a contest began to see who could pen the most devastating critical review of it, the one that best satisfies our desperate urge to dismiss Wade’s arguments and reinforce our faith in the futility of studying biological differences between human races, a faith backed up by a cherished official consensus ever so conveniently in line with our moral convictions. That Charles Murray, one of the authors of the evil tome The Bell Curve, wrote an early highly favorable review for the Wall Street Journal only upped the stakes for all would-be champions of liberal science. Even as the victor awaits crowning, many scholars are posting links to their favorite contender’s critiques all over social media to advertise their principled rejection of this book they either haven’t read yet or have no intention of ever reading.

You don’t have to go beyond the title, A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History, to understand what all these conscientious intellectuals are so eager to distance themselves from—and so eager to condemn. History has undeniably treated some races much more poorly than others, so if their fates are in any small way influenced by genes the implication of inferiority is unavoidable. Regardless of what he actually says in the book, Wade’s very program strikes many as racist from its inception.

The going theories for the dawn of the European Enlightenment and the rise of Western culture—and western people—to global ascendency attribute the phenomenon to a combination of geographic advantages and historical happenstance. Wade, along with many other scholars, finds such explanations unsatisfying. Geography can explain why some societies never reached sufficient population densities to make the transition into states. “Much harder to understand,” Wade writes, “is how Europe and Asia, lying on much the same lines of latitude, were driven in the different directions that led to the West’s dominance” (223). Wade’s theory incorporates elements of geography—like the relatively uniform expanse of undivided territory between the Yangtze and Yellow rivers that facilitated the establishment of autocratic rule, and the diversity of fragmented regions in Europe preventing such consolidation—but he goes on to suggest that these different environments would have led to the development of different types of institutions. Individuals more disposed toward behaviors favored by these institutions, Wade speculates, would be rewarded with greater wealth, which would in turn allow them to have more children with behavioral dispositions similar to their own.

After hundreds of years and multiple generations, Wade argues, the populations of diverse regions would respond to these diverse institutions by evolving subtly different temperaments. In China for instance, favorable, and hence selected for traits may have included intelligence, conformity, and obedience. These behavioral propensities would subsequently play a role in determining the future direction of the institutions that fostered their evolution. Average differences in personality would, according to Wade, also make it more or less likely that certain new types of institution would arise within a given society, or that they could be successfully transplanted into it. And it’s a society’s institutions that ultimately determine its fate relative to other societies. To the objection that geography can, at least in principle, explain the vastly different historical outcomes among peoples of specific regions, Wade responds, “Geographic determinism, however, is as absurd a position as genetic determinism, given that evolution is about the interaction between the two” (222).

East Asians score higher on average on IQ tests than people with European ancestry, but there’s no evidence that any advantage they enjoy in intelligence, or any proclivity they may display toward obedience and conformity—traits supposedly manifest in their long history of autocratic governance—is attributable to genetic differences as opposed to traditional attitudes toward schoolwork, authority, and group membership inculcated through common socialization practices. So we can rest assured that Wade’s just-so story about evolved differences between the races in social behavior is eminently dismissible. Wade himself at several points throughout A Troublesome Inheritance admits that his case is wholly speculative. So why, given the abominable history of racist abuses of evolutionary science, would Wade publish such a book?

It’s not because he’s unaware of the past abuses. Indeed, in his second chapter, titled “Perversions of Science,” which none of the critical reviewers deigns to mention, Wade chronicles the rise of eugenics and its culmination in the Holocaust. He concludes,

After the Second World War, scientists resolved for the best of reasons that genetics research would never again be allowed to fuel the racial fantasies of murderous despots. Now that new information about human races has been developed, the lessons of the past should not be forgotten and indeed are all the more relevant. (38)

The convention among Wade’s critics is to divide his book into two parts, acknowledge that the first is accurate and compelling enough, and then unload the full academic arsenal of both scientific and moral objections to the second. This approach necessarily scants a few important links in his chain of reasoning in an effort to reduce his overall point to its most objectionable elements. And for all their moralizing, the critics, almost to a one, fail to consider Wade’s expressed motivation for taking on such a fraught issue.

Even acknowledging Wade’s case is weak for the role of biological evolution in historical developments like the Industrial Revolution, we may still examine his reasoning up to that point in the book, which may strike many as more firmly grounded. You can also start to get a sense of what was motivating Wade when you realize that the first half of A Troublesome Inheritance recapitulates his two previous books on human evolution. The first, Before the Dawn, chronicled the evolution and history of our ancestors from a species that resembled a chimpanzee through millennia as tribal hunter-gatherers to the first permanent settlements and the emergence of agriculture. Thus, we see that all along his scholarly interest has been focused on major transitions in human prehistory.

While critics of Wade’s latest book focus almost exclusively on his attempts at connecting genomics to geopolitical history, he begins his exploration of differences between human populations by emphasizing the critical differences between humans and chimpanzees, which we can all agree came about through biological evolution. Citing a number of studies comparing human infants to chimps, Wade writes in A Troublesome Inheritance,