READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Putting Down the Pen: How School Teaches Us the Worst Possible Way to Read Literature

Far too many literature teachers encourage us to treat great works like coded messages with potentially harmful effects on society. Thus, many of us were taught we needed to resist being absorbed by a story and enchanted by language—but aren’t those the two parts of reading we’re most excited about enjoying?

Storytelling comes naturally to humans. But there is a special category of narratives that we’re taught from an early age to approach in the most strained and unnatural of ways. The label we apply to this category is literature. While we demand of movies and television shows that they envelop us in the seamlessly imagined worlds of their creators’ visions, not only whisking us away from our own concerns, but rendering us oblivious as well, however fleetingly, to the artificiality of the dramas playing out before us, we split the spines of literary works expecting some real effort at heightened awareness to be demanded of us—which is why many of us seldom read this type of fiction at all.

Some of the difficulty is intrinsic to the literary endeavor, reflecting the authors’ intention to engage our intellect as well as our emotions. But many academics seem to believe that literature exists for the sole purpose of supporting a superstructure of scholarly discourse. Rather than treating it as an art form occupying a region where intuitive aesthetic experience overlaps with cerebral philosophical musing, these scholars take it as their duty to impress upon us the importance of approaching literature as a purely intellectual exercise. In other words, if you allow yourself to become absorbed in the story, especially to the point where you forget, however briefly, that it is just a story, then you’re breaking faith with the very institutions that support literary scholarship—and that to some degree support literature as an art form.

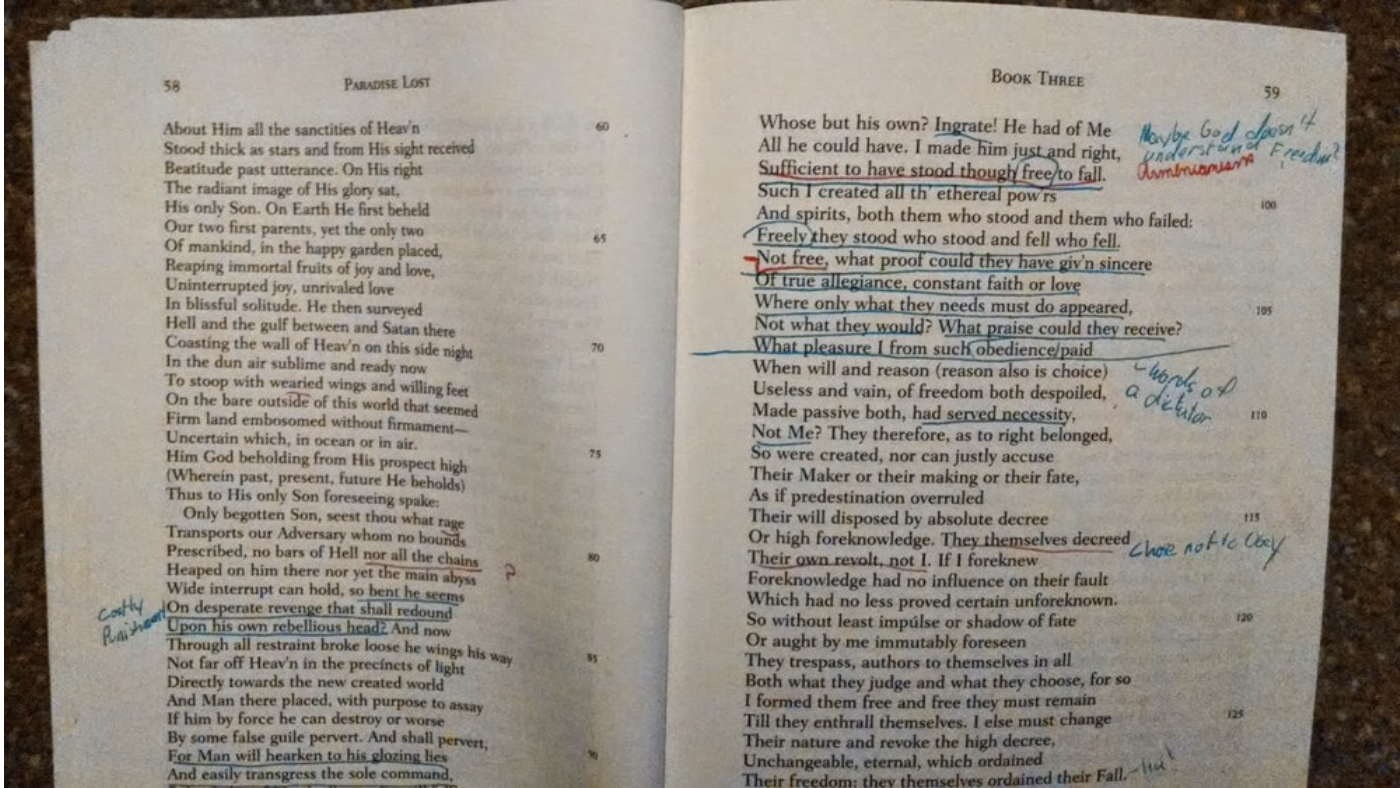

The unremarked scandal of modern literary scholarship is that the tension between reading as an aesthetic experience and reading as a purely intellectual pursuit is never even acknowledged. Many students seeking a deeper and more indelible involvement with great works come away instead with instructions on how to take on a mindset and apply a set of methods designed specifically to preclude just the type of experience they’re hoping to achieve. For instance, when novelist and translator Tim Parks wrote an essay called “A Weapon for Readers” for The New York Review of Books, in which he opined on the critical importance of having a pen in hand while reading, he received several emails from disappointed readers who “even thus armed felt the text was passing them by.” In a response titled “How I Read,” Parks begins with an assurance that he will resist being “prescriptive” as he shares his own reading methods, and yet he goes on to profess, “I do believe reading is an active skill, an art even, certainly not a question of passive absorption.” But, we might ask, could there also be such a state as active absorption? And isn’t that what most of us are hoping for when we read a story?

For Parks, and nearly every academic literary scholar writing or teaching today, stories are vehicles for the transmission of culture and hence reducible to the propositional information contained within them. The task of the scholar and the responsible reader alike therefore is to penetrate the surface effects of the story—the characters, the drama, the music of the prose—so we can scrutinize the underlying assumptions that hold them all together and make them come to life. As author David Shields explains in his widely celebrated manifesto Reality Hunger, “I always read the book as an allegory, as a disguised philosophical argument.” Parks demonstrates more precisely what this style of reading entails, writing, “As I dive into the opening pages, the first question I’m asking is, what are the qualities or values that matter most to this author, or at least in this novel?” Instead of pausing to focus on character descriptions or to take any special note of the setting, he aims his pen at clues to the author’s unspoken preoccupations:

I start a novel by Hemingway and at once I find people taking risks, forcing themselves toward acts of courage, acts of independence, in a world described as dangerous and indifferent to human destiny. I wonder if being courageous is considered more important than being just or good, more important than coming out a winner, more important than comradeship. Is it the dominant value? I’m on the lookout for how each character positions himself in relation to courage.

We can forget for a moment that Parks’ claim is impossible—how could he start a novel with so much foreknowledge of what it contains? The important point revealed in this description is that from the opening pages Parks is searching for ways to leap from the particular to the abstract, from specific incidents of the plot to general propositions about the world and the people in it. He goes on,

After that the next step is to wonder what is the connection between these force fields—fear/courage, belonging/exclusion, domination/submission—and the style of the book, the way the plot unfolds. How is the writer trying to draw me into the mental world of his characters through his writing, through his conversation with me?

While this process of putting the characters in some relation to each other and the author in relation to the reader is going on, another crucial question is hammering away in my head. Is this a convincing vision of the world?

Like Shields, Parks is reducing stories to philosophical arguments. And he proceeds to weigh them according to how well they mesh with his own beliefs.

Parks addresses the objection that his brand of critical reading, which he refers to as “alert resistance,” will make us much less likely to experience “those wonderful moments when we might fall under a writer’s spell” by insisting that there will be time enough for that after we’ve thoroughly examined the text for dangerous hidden assumptions, and by further suggesting that many writers will have worked hard enough on their texts to survive our scrutiny. For Parks and other postmodern scholars, there’s simply too much at stake for us to allow ourselves to be taken in by a good story until it’s been properly scanned for contraband ideas. “Sometimes it seems the whole of society languishes in the stupor of the fictions it has swallowed,” he writes. Because it’s a central tenet of postmodernism, the ascendant philosophy in English departments across the country, Parks fails to appreciate just how extraordinary a claim he’s making when he suggests that writers of literary texts are responsible, at least to some degree, for all the worst ills of society.

The sickening irony is that postmodern scholars are guilty of the very crime they accuse literary authors of committing. Critics like Parks and Shields charge that writers dazzle us with stories so they can secretly inculcate us with their ideologies. Parks feels he needs to teach readers “to protect themselves from all those underlying messages that can shift one’s attitude without one’s being aware of it.” And yet when his own readers come to him looking for advice on how to experience literature more deeply he offers them his own ideology disguised as the only proper way to approach a text (politely, of course, since he wouldn’t want to be prescriptive). Consider the young booklover attending her first college lit courses and being taught the importance of putting literary works and their authors on trial for their complicity in societal evils: she comes believing she’s going to read more broadly and learn to experience more fully what she reads, only to be tricked into thinking what she loves most about books are the very things that must be resisted.

Parks is probably right in his belief that reading with a pen and looking for hidden messages makes us more attentive to the texts and increases our engagement with them. But at what cost? The majority of people in our society avoid literary fiction altogether once they’re out of school precisely because it’s too difficult to get caught up in the stories the way we all do when we’re reading commercial fiction or watching movies. Instead of seeing their role as helping students experience this absorption with more complex works, scholars like Parks instruct us on ways to avoid becoming absorbed at all. While at first the suspicion of hidden messages that underpins this oddly counterproductive approach to stories may seem like paranoia, the alleged crimes of authors often serve to justify an attitude toward texts that’s aggressively narcissistic—even sadistic. Here’s how Parks describes the outcome of his instructions to his students:

There is something predatory, cruel even, about a pen suspended over a text. Like a hawk over a field, it is on the lookout for something vulnerable. Then it is a pleasure to swoop and skewer the victim with the nib’s sharp point. The mere fact of holding the hand poised for action changes our attitude to the text. We are no longer passive consumers of a monologue but active participants in a dialogue. Students would report that their reading slowed down when they had a pen in their hand, but at the same time the text became more dense, more interesting, if only because a certain pleasure could now be taken in their own response to the writing when they didn’t feel it was up to scratch, or worthy only of being scratched.

It’s as if the author’s first crime, the original sin, as it were, was to attempt to communicate in a medium that doesn’t allow anyone to interject or participate. By essentially shouting writers down by marking up their works, Parks would have us believe we’re not simply being like the pompous idiot who annoys everyone by trying to point out all the holes in movie plots so he can appear smarter than the screenwriters—no, we’re actually making the world a better place. He even begins his essay on reading with a pen with this invitation: “Imagine you are asked what single alteration in people’s behavior might best improve the lot of mankind.”

The question postmodern literary scholars never get around to answering is, given that they believe books and stories are so far-reaching in their insidious effects, and given that they believe the main task in reading is to resist the author’s secret agenda, why should we bother reading in the first place? Of course, we should probably first ask if it’s even true that stories have such profound powers of persuasion. Jonathan Gottschall, a scholar who seeks to understand storytelling in the context of human evolution, may seem like one of the last people you’d expect to endorse the notion that every cultural artifact emerging out of so-called Western civilization must be contaminated with hidden reinforcements of oppressive ideas. But in an essay that seemingly echoes Parks’ most paranoid pronouncements about literature, one that even relies on similarly martial metaphors, Gottschall reports,

Results repeatedly show that our attitudes, fears, hopes, and values are strongly influenced by story. In fact, fiction seems to be more effective at changing beliefs than writing that is specifically designed to persuade through argument and evidence.

What is going on here? Why are we putty in a storyteller’s hands? The psychologists Melanie Green and Tim Brock argue that entering fictional worlds “radically alters the way information is processed.” Green and Brock’s studies show that the more absorbed readers are in a story, the more the story changes them. Highly absorbed readers also detected significantly fewer “false notes” in stories—inaccuracies, missteps—than less transported readers. Importantly, it is not just that highly absorbed readers detected the false notes and didn’t care about them (as when we watch a pleasurably idiotic action film). They were unable to detect the false notes in the first place.

Gottschall’s essay is titled “Why Storytelling Is the Ultimate Weapon,” and one of his main conclusions seems to corroborate postmodern claims about the dangers lurking in literature. “Master storytellers,” he writes, “want us drunk on emotion so we will lose track of rational considerations, relax our skepticism, and yield to their agenda.”

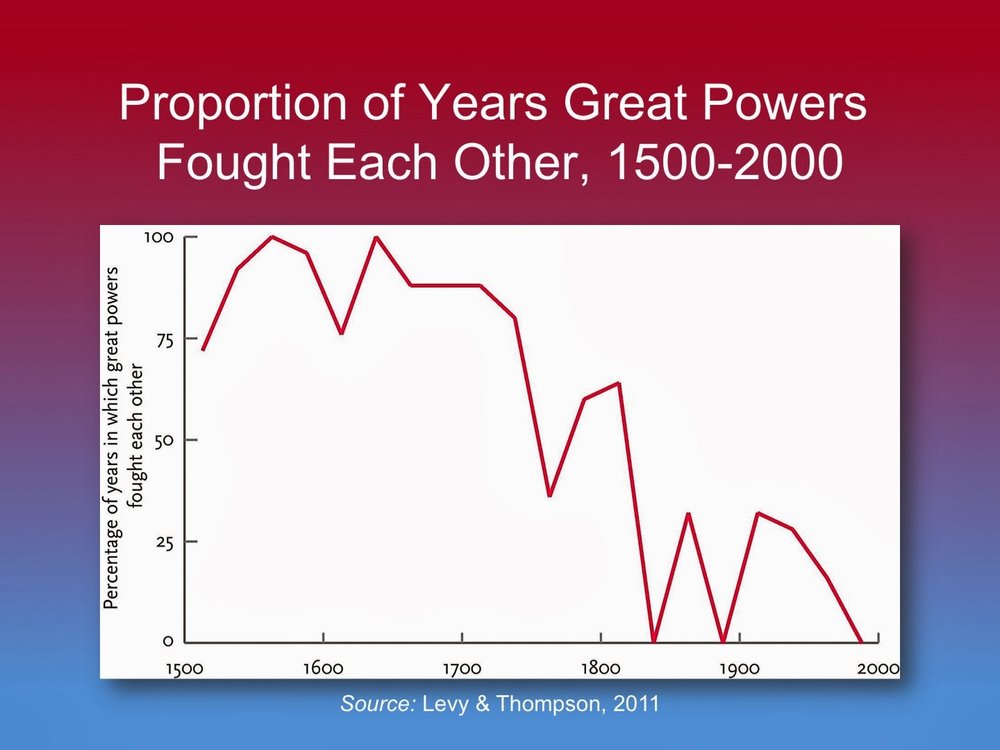

Should we just accept Shields’ point then that stories are no more than disguised attempts at persuasion? Should we take Parks’ advice and start scouring our books for potentially nefarious messages? It’s important to note that Gottschall isn’t writing about literature in his essay; rather, he’s discussing storytelling in the context of business and marketing. And this brings up another important point: as Gottschall writes, “story is a tool that can be used for good or ill.” Just because there’s a hidden message doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a bad one. Indeed, if literature really were some kind of engine driving the perpetuation of all the most oppressive aspects of our culture, then we would expect the most literate societies, and the most literate sectors within each society, to be the most oppressive. Instead, some scholars, from Lynn Hunt to Steven Pinker, have traced liberal ideas like universal human rights to the late eighteenth century, when novels were first being widely read. The nature of the relationship is nearly impossible to pin down with any precision, but it’s clear that our civilization’s thinking about human rights evolved right alongside its growing appreciation for literature.

A growing body of research demonstrates that people who read literary fiction tend to be more empathetic—and less racist even. If literature has hidden messages, they seem to be nudging us in a direction not many would consider cause for alarm. It is empathy after all that allows us to enter into narratives in the first place, so it’s hardly a surprise that one of the effects of reading is a strengthening of this virtue. And that gets at the fundamental misconception at the heart of postmodern theories of narrative. For Shields and Parks, stories are just clever ways to package an argument, but their theories leave unanswered why we enjoy all those elements of narratives that so distract us from the author’s supposed agenda. What this means is that postmodern scholars are confused about what a story even is. They don’t understand that the whole reason narratives have such persuasive clout is that reading them brings us close to actual experiences, simulating what it would be like to go through the incidents of the plots alongside the characters. And, naturally, experiences tend to be more persuasive than arguments. When we’re absorbed in a story, we fail to notice incongruities or false notes because in a very real sense we see them work just fine right before our mind’s eye. Parks worries that readers will passively absorb arguments, so he fails to realize that the whole point of narratives is to help us become actively absorbed in their simulated experiences.

So what is literature? Is it pure rhetoric, pure art, or something in between? Do novelists begin conceiving of their works when they have some philosophical point to make and realize they need a story to cloak it in? Or are any aspects of their stories that influence readers toward one position or another merely incidental to the true purpose of writing fiction? Consider these questions in the light of your own story consuming habits. Do you go to a movie to have your favorite beliefs reinforced? Or do you go to have a moving experience? Or we can think of it in relation to other art forms. Does the painter arrange colors on a canvas to convince us of some point? Are we likely to vote differently after attending a symphony? The best art really does impact the way we think and feel, but that’s because it creates a moving experience, and—perhaps the most important point here—that experience can seldom be reduced to a single articulable proposition. Think about your favorite novel and try to pare it down to a single philosophical statement, or even ten statements. Now compare that list of statements to the actual work.

Another fatal irony for postmodernism is that literary fiction, precisely because it requires special effort to appreciate, is a terribly ineffective medium for propaganda. And exploring why this is the case will start getting us into the types of lessons professors might be offering their students if they were less committed to their bizarre ideology than they were to celebrating literature as an art form. If we compare literary fiction to commercial fiction, we see that the prior has at least two disadvantages when it comes to absorbing our attention. First, literary writers are usually committed to realism, so the events of the plot have to seem like they may possibly occur in the real world, and the characters have to seem like people you could actually meet. Second, literary prose often relies on a technique known as estrangement, whereby writers describe scenes and experiences in a way that makes readers think about them differently than they ever have before, usually in the same way the character guiding the narration thinks of them. The effect of these two distinguishing qualities of literature is that you have less remarkable plots recounted in remarkably unfamiliar language, whereas with commercial fiction you have outrageous plots rendered in the plainest of terms.

Since it’s already a challenge to get into literary stories, the notion that readers need to be taught how to resist their lures is simply perverse. And the notion that an art form that demands so much thought and empathy to be appreciated should be treated as some kind of delivery package for oppressive ideas is just plain silly—or rather it would be if nearly the entirety of American academia weren’t sold on it. I wonder if Parks sits in movie theaters violently scribbling in notebooks lest he succumb to the dangerous messages hidden in Pixar movies (like that friends are really great!). Our lives are pervaded by stories—why focus our paranoia on the least likely source of unacceptable opinions? Why assume our minds are pristinely in the right before being influenced? Of course, one of the biggest influences on our attitudes and beliefs, surely far bigger than any single reading of a book, is our choice of friends. Does Parks vet candidates for entrance into his social circle according to some standard of political correctness? For that matter, does he resist savoring his meals by jotting down notes about suspect ingredients, all the while remaining vigilant lest one of his dining partners slip in some indefensible opinion while he’s distracted with chewing?

Probably the worst part of Parks’ advice to readers on how to get more out of literature is that he could hardly find a better way to ensure that their experiences will be blunted than by encouraging them to move as quickly as possible from the particular to the abstract and from the emotional to the intellectual. Emotionally charged experiences are the easiest to remember, dry abstractions the most difficult. If you want to get more out of literature, if you want to become actively absorbed in it, then you’ll need to forget about looking past the words on the page in search of confirmation for some pet theory. There’s enough ambiguity in good fiction to support just about any theory you’re determined to apply. But do you really want to go to literature intent on finding what you already think you know? Or would you rather go in search of undiscovered perspectives and new experiences?

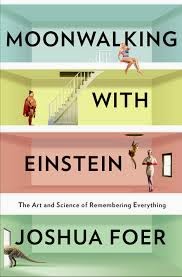

I personally stopped reading fiction with a pen in my hand—and even stopped using bookmarks—after reading Moonwalking with Einstein, a book on memory and competitive mnemonics by science writer Joshua Foer. A classic of participatory journalism, the book recounts Foer's preparation for the U.S. Memory Championships, and along the way it explores the implications of our culture’s continued shift toward more external forms of memory, from notes and books, to recorders and smartphones. Since one of the major findings in the field of memory research is that you can increase your capacity with the right kind of training, Foer began looking for opportunities to memorize things. He writes,

I started trying to use my memory in everyday life, even when I wasn’t practicing for the handful of arcane events that would be featured in the championship. Strolls around the neighborhood became an excuse to memorize license plates. I began to pay a creepy amount of attention to name tags. I memorized my shopping lists. I kept a calendar on paper, and also in my mind. Whenever someone gave me a phone number, I installed it in a special memory palace. (163-4)

Foer even got rid of all the sticky notes around his computer monitor, except for one which read, “Don’t forget to remember.”

The most basic technique in mnemonics is what cognitive scientists call “elaborative encoding,” which means you tag otherwise insignificant items like numbers or common names with more salient associations, usually some kind of emotionally provocative imagery. After reading Foer’s book, it occurred to me that while the mnemonics masters went about turning abstractions into solid objects and people, literary scholars are busy insisting that we treat fictional characters as abstractions. Authors, in applying the principle of estrangement to their descriptions, are already doing most of the work of elaborately encoding pertinent information for us. We just to have to accept their invitations to us and put the effort into imagining what they describe.

A study I came across sometime after reading Foer’s book illustrates the tradeoff between external and internal memories. Psychologist Linda Henkel compared the memories of museum visitors who were instructed to take pictures to those of people who simply viewed the various displays, and she found that taking pictures had a deleterious effect on recall. What seems to be occurring here is that museum visitors who don’t take pictures are either more motivated to get the full experience by mentally taking in all the details or simply less distracted by the mechanics of picture-taking. People with photos know they can rely on them as external memories, so they’re quicker to shift their attention to other things. In other words, because they’re storing parts of the present moment for the future, they have less incentive to occupy the present moment—to fully experience it—with the result that they don’t remember it as well.

If I’m reading nonfiction, or if I’m reading a work of fiction I’ve already read before in preparation for an essay or book discussion, I’ll still pull out a pen once in a while. But the first time I read a work of literature I opt to follow Foer’s dictum, “Don’t forget to remember,” instead of relying on external markers. I make an effort to cast myself into the story, doing my best to think of the events as though they were actually happening before my eyes and think of the characters as though they were real people—if an author is skilled enough and generous enough to give a character a heartbeat, who are we to drain them of blood? Another important principle of cognitive psychology is that “Memory is the residue of thought.” So when I’m reading I take time—usually at section breaks—to think over what’s already happened and wonder at what may happen next.

I do eventually get around to thinking about abstractions like the author’s treatment of various themes and what the broader societal implications might be of the particular worldview represented in the story, insofar as there is a discernable one. But I usually save those topics for the times when I don’t actually have the book in my hands. It’s much more important to focus on the particulars, on the individual words and lines, so you can make the most of the writer’s magic and transform the marks on the page into images in your mind. I personally think it’s difficult to do that when you’re busy making your own marks on the pages. And I also believe we ought to have the courage and openheartedness to give ourselves over to great authors—at least for a while—confident in our ability to return from where they take us if we deem it necessary. Once in a while, the best thing to do is just shut up and listen.

Also read:

And:

REBECCA MEAD’S MIDDLEMARCH PILGRIMAGE AND THE 3 WRONG WAYS TO READ A NOVEL

And:

Sabbath Says: Philip Roth and the Dilemmas of Ideological Castration

The Creepy King Effect: Why We Can't Help Confusing Writers with Their Characters

Authors often serve as mental models helping readers imagine protagonists. This can be disconcerting when the protagonist engage in unsavory behavior. Is Stephen King as scary as his characters? Probably not, we all know, but the workings of his imagination are enough to make us wonder just a bit.

Every writer faces this conundrum: your success hinges on your ability to create impressions that provoke emotions in the people who read your work, so you need feedback from a large sample of readers to gauge the effect of your writing. Without feedback, you have no way to calibrate the impact of your efforts and thus no way to hone your skills. This is why writers’ workshops are so popular; they bring a bunch of budding authors together to serve as one another’s practice audience. The major drawback to this solution is that a sample composed of fellow authorly aspirants may not be representative of the audience you ultimately hope your work will appeal to.

Whether or not they attend a workshop, all writers avail themselves of the ready-made trial audience comprised of their family and friends, a method which inevitably presents them with yet another conundrum: anyone who knows the author won’t be able to help mixing her up with her protagonists. The danger isn’t just that the feedback you get will be contaminated with moral judgments and psychological assessments; you also risk offending people you care about who will have a tough time not assuming identify with characters who bear even the most superficial resemblance to them. And of course you risk giving everyone the wrong idea about the type of person you are and the type of things you get up to.

My first experience of being mistaken for one of my characters occurred soon after I graduated from college. A classmate and fellow double-major in psychology and anthropology asked to read a story I’d mentioned I was working on. Desperate for feedback, I emailed it to her right away. The next day I opened my inbox to find a two-page response to the story which treated everything described in it as purely factual and attempted to account for the emotional emptiness I’d demonstrated in my behavior and commentary. I began typing my own response explaining I hadn’t meant the piece to be taken as a memoir—hence the fictional name—and pointing to sections she’d missed that were meant to explain why the character was emotionally empty (I had deliberately portrayed him that way), but as I composed the message I found myself getting angry. As a writer of fiction, you trust your readers to understand that what you’re writing is, well, fiction, regardless of whether real people and real events figure into it to some degree. I felt like that trust had been betrayed. I was being held personally responsible for behaviors and comments that for all she knew I had invented whole-cloth for the sake of telling a good story.

To complicate matters, the events in the story my classmate was responding to were almost all true. And yet it still seemed tremendously unfair for anyone to have drawn conclusions about me based on it. The simplest way to explain this is to point out that you have an entirely different set of goals if you’re telling a story about yourself to a friend than you do if you’re telling a story about a fictional character to anyone who might read it—even if they’re essentially the same story. And your goals affect your choice of not only which events to include, but which aspects of the situation and which traits of the characters to focus on. Add in even a few purely fabricated elements and you can dramatically alter the readers’ impression of the characters.

Another way to think about this is to imagine how boring fiction would be if all authors knew they would be associated with and held accountable for everything their protagonists do or say. This is precisely why it’s so important to avoid mistaking writers for their characters, and why writers feel betrayed when that courtesy isn’t afforded to them. Unfortunately, that courtesy is almost never afforded to them. Indeed, if you call readers out for conflating you with your characters, many of them will double down on their mistake. As writers who feel our good names should be protected under the cover of the fiction label, we have to accept that human psychology is constantly operating to poke giant holes in that cover.

Let’s try an experiment: close your eyes for a moment and try to picture Jay Gatsby’s face in your mind’s eye. If you’re like me, you imagined one of two actors who played Gatsby in the movie versions, either Leonardo DiCaprio or Robert Redford. The reason these actors come so readily to mind is that imagining a character’s face from scratch is really difficult. What does Queequeq look like? Melville describes him in some detail; various illustrators have given us their renditions; a few actors have portrayed him, albeit never in a film you’d bother watching a second time. Since none of these movies is easily recallable, I personally have to struggle a bit to call an image of him to mind. What’s true of characters’ physical appearances is also true of nearly everything else about them. Going from words on a page to holistic mental representations of human beings takes effort, and even if you put forth that effort the product tends to be less than perfectly vivid and stable.

In lieu of a well-casted film, the easiest shortcut to a solid impression is to substitute the author you know for the character you don’t. Actors are also mistaken for their characters with disturbing frequency, or at least assumed to possess similar qualities. (“I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV.”) To be fair, actors are chosen for roles they can convincingly pull off, and authors, wittingly or otherwise, infuse their characters with tinctures of their own personalities. So it’s not like you won’t ever find real correspondences.

You can nonetheless count on your perception of the similarities being skewed toward gross exaggeration. This is owing to a phenomenon social psychologists call the fundamental attribution error. The basic idea is that, at least in individualist cultures, people tend to attribute behavior to the regular inclinations of the person behaving as opposed to more ephemeral aspects of the situation: the driver who cut you off is inconsiderate and hasty, not rushing to work because her husband’s car broke down and she had to drop him off first. One of the classic experiments on this attribution bias had subjects estimate people’s support for Fidel Castro based on an essay they’d written about him. The study, conducted by Edward Jones and Victor Harris at the height of the Cold War, found that even if people were told that the author was assigned a position either for or against Castro based on a coin toss they still assumed more often than not that the argument reflected the author’s true beliefs.

The implication of Jones and Harris’s findings is that even if an author tries to assure everyone that she was writing on behalf of a character for the purpose of telling a story, and not in any way trying to use that character as a mouthpiece to voice some argument or express some sentiment, readers are still going to assume she agrees with everything her character thinks and says. As readers, we can’t help giving too little weight to the demands of the story and too much weight to the personality of the author. And writers can’t even count on other writers not to be biased in this way. In 2001, Eric Hansen, Charles Kimble, and David Biers conducted a series of experiments that instructed people to treat a fellow study participant in either a friendly or unfriendly way and then asked them to rate each other on friendliness. Even though they all got the same type of instructions, and hence should have appreciated the nature of the situational influences, they still attributed unfriendliness in someone else to that person’s disposition. Of course, their own unfriendliness they attributed to the instructions.

One of the theories for why we Westerners fall prey to the fundamental attribution error is that creating dual impressions of someone’s character takes a great deal of effort. Against the immediate and compelling evidence of actual behavior, we have nothing but an abstract awareness of the possibility that the person may behave differently in different circumstances. The ease of imagining a person behaving similarly even without situational factors like explicit instructions makes it seem more plausible, thus creating the illusion that we can somehow tell whether someone following instructions, performing a scene, or writing on behalf of a fictional character is being sincere—and naturally enough we nearly always think they are.

The underlying principle here—that we’re all miserly with our cognition—is bad news for writers for yet another reason. Another classic study, this one conducted by Daniel Gilbert and his colleagues, was reported in an article titled “You Can’t Not Believe Everything You Read,” which for a fiction writer sounds rather heartening at first. The experiment asked participants to determine prison sentences for defendants in imaginary court cases based on statements that were color-coded to signal they were either true or false. Even though some of the statements were marked as false, they still affected the length of the sentences, and the effect grew even more pronounced when the participants were distracted or pressed for time.

The researchers interpret these findings to mean that believing a statement is true is crucial to comprehending it. To understand the injunction against thinking of a pink elephant, you have to imagine the very pink elephant you’re not supposed to think about. Only after comprehension is achieved can you then go back and tag a statement as false. In other words, we automatically believe what we hear or read and only afterward, with much cognitive effort, go back and revise any conclusions we arrived at based on the faulty information. That’s why sentences based on rushed assessments were more severe—participants didn’t have enough time to go back and discount the damning statements that were marked as false.

If those of us who write fiction assume that our readers rely on the cognitive shortcut of substituting us for our narrators or protagonists, Hansen et al’s and Gilbert’s findings suggest yet another horrifying conundrum. The more the details of our stories immerse readers in the plot, the more difficulty they’re going to have taking into account the fictional nature of the behaviors being enacted in each of the scenes. So the more successful you are in writing your story, the harder it’s going to be to convince anyone you didn’t do the things you so expertly led them to envision you doing. And I suspect, even if readers know as a matter of fact you probably didn’t enact some of the behaviors described in the story, their impressions of you will still be influenced by a sort of abstract association between you and the character. When a reader seems to be confusing me with my characters, I like to pose the question, “Did you think Stephen King wanted to kill his family when you read The Shining?” A common answer I get is, “No, but he is definitely creepy.” (After reading King’s nonfiction book On Writing, I personally no longer believe he’s creepy.)

When people talk to me about stories of mine they’ve read, they almost invariably use “you” as a shorthand for the protagonist. At least, that’s what I hope they’re doing—in many cases, though, they betray no awareness of the story as a story. To them, it’s just a straightforward description of some real events. Of course, when you press them they allow for some creative license; they’ll acknowledge that maybe it didn’t all happen exactly as it’s described. But that meager allowance still tends to leave me pretty mortified. Once, I even had a family member point to some aspects of a character that were recognizably me and suggest that they undermined the entire story because they made it impossible for her to imagine the character as anyone but me. In her mind, my goal in writing was to disguise myself behind the character, but I’d failed to suppress my true feelings. I tried to explain that I hadn’t tried to hide anything; I’d included elements of my own life deliberately because they served what were my actual goals. I don’t think she was convinced. At any rate, I never got any good feedback from her because she simply didn’t understand what I was really trying to do with the story. And ever since I’ve been taking a reader’s use of “you” to refer to the protagonist as an indication that I’ll need to go elsewhere for any useful commentary.

I’m pretty sure all fiction writers incorporate parts of their own life stories into their work. I’d even go so far as to posit that, at least for literary writers, creating plots and characters is more a matter of rearranging bits and pieces of real events and real people’s sayings and personalities into a coherent sequence with a beginning, middle, and end—a dilemma, resolution, and outcome—than it is of conjuring scenes and actors out of the void. But even a little of this type of rearranging is enough to make any judgments about the author seem pretty silly to anyone who can put the true details back together in their original order. The problem is the author is often the only one who knows what parts are true and how they actually happened, so you’re left having to simply ask her what she really thinks, what she really feels, and what she’s really done. For everyone else, the story only seems like it can tell them something when they already know whatever it is it might tell them. So they end up being tricked into making the leap from bits and pieces of recognizable realities to an assumption of general truthiness.

Even the greatest authors get mixed up in people’s minds with their characters. People think Rabbit Angstrom and John Updike are the same person—or at least that the character is some kind of distillation of the author. Philip Roth gets mistaken for both Nathan Zuckerman (though Roth seems to have wanted that to happen) and Mickey Sabbath, two very different characters. I even wonder if readers assume some kinship between Hilary Mantel and her fictional version of Thomas Cromwell. So I have to accept that my goal with this essay is ridiculously ambitious. As long as I write, people are going to associate me with my narrators and protagonists to one degree or another.

********

Nevertheless, I’m going to do something that most writers are loath to do. I’m going to retrace the steps that went into the development of my latest story so everyone can see what I mean when I say I’m responding to the demands of the story or making characters serve the goals of the story. By doing so, I hope to show how quickly real life character models and real life events get muddled, and why there could never be anything like a straightforward method for drawing conclusions about the author based on his or her characters.

The story is titled The Fire Hoarder and it follows a software engineer nearing forty who decides to swear off his family and friends for an indefinite amount of time because he’s impatient with their complacent mediocrity and feels beset by their criticisms, which he perceives as expressions of envy and insecurity. My main inspirations were a series of conversations with a recently divorced friend about the detrimental effects of marriage and parenthood on a man’s identity, a beautiful but somehow eerie nature preserve in my hometown where I fell into the habit of taking weekly runs, and the HBO series True Detective.

The newly divorced friend, whom I’ve known for almost twenty years, became a bit of a fitness maniac over this past summer. Mainly through grueling bike rides, he lost all the weight he’d put on since what he considered his physical prime, going from something like 235 to 190 pounds in the span of few months. Once, in the midst of a night of drinking, he began apologizing for all the time he’d been locked away, gaining weight, doing nothing with his life. He said he felt like he’d let me down, but I have to say it hadn’t ever occurred to me to take it personally. Months later, in the process of writing my story, I realized I needed some kind of personal drama in the protagonist’s life, something he would already be struggling with when the instigating events of the plot occurred.

So my divorced friend, who turned 39 this summer (I’m just turning 37 myself), ended up serving as a partial model for two characters, the protagonist who is determined to get in better shape, and the friend who betrays him by being too comfortable and lazy in his family life. He shows up again in the words of yet another character, a police detective and tattoo artist who tries to convince the protagonist that single life is better than married life. Though, as one of the other models for that character, an actual police detective and tattoo artist, was quick to notice, the cop in the story is based on a few other people as well.

My own true detective meets the protagonist at a bar after the initial scene. The problem I faced with this chapter was that the main character had already decided to forswear socializing. I handled this by describing the relationship between the characters as one that didn’t include any kind of intimate revelations or profound exchanges—except when it did (like in this particular scene). “Oh man,” read the text I got from the real detective, “I hope I am not as shallow of a friend as Ray is to Russell?” And this is a really good example of how responding to the demands of the story can give the wrong impression to anyone looking for clues about the author’s true thoughts and feelings. (He later assured me he was just busting my balls.)

Russell’s name was originally Steve; I changed it late in the writing process to serve as an homage to Rustin Cohle, one of the lead characters in True Detective. Before I ever even began watching the show, one of my brothers, the model for Russell’s brother Nick, compared me to Rust. He meant it as a compliment, but a complicated one. Like all brothers, our relationship is complimentary, but complicated. A few of the things my brother has said that have annoyed me over the past few years show up in the story, but whereas this type of commentary is subsumed in our continuing banter, which is almost invariably good-humored, it really gets under Russell’s skin. In a story, one of the goals is to give texture to the characters’ backgrounds, and another goal is often to crank up the tension. So I often include more serious versions of petty and not-so-memorable spats I have with friends, lovers, and family members in my plots and character bios. And when those same friends, lovers, and family members read the resulting story I have to explain that it doesn’t mean what they think it means. (I haven’t gotten any texts from my brother about the story yet.) I won't go into the details of my love life here; suffice it to say writers pretty much have to be prepared for their wives or girlfriends to flip out whenever they read one of their stories featuring fictional wives or girlfriends.

I was initially put off by True Detective for the same reasons I have a hard time stomaching any hardboiled fiction. The characters use the general foulness of the human race to justify their own appalling behavior. “The world needs bad men,” Rust says to his partner. “They keep the other bad men from the door.” The conceit is that life is so ugly and people are so evil that we should all just walk around taking ourselves far too seriously as we bemoan the tragedy of existence. At one point, Rust tells some fellow detectives about M-theory, an outgrowth of superstring theory. The show tries to make it sound tragic and horrifying. But the tone of the scene is perfectly nonsensical. Why should thinking about extra dimensions be like rubbing salt in our existential wounds? The view of the world that emerges is as embarrassingly adolescent as it is screwball.

But much of the dialogue in the show is magnificent, and the scene-by-scene progression of the story is virtuoso. When I first watched it, the conversations about marriage and family life resonated with the discussions I’d been having with my divorced friend over the summer. And Rust in particular forces us to ask what becomes of a man who finds the common rituals and diversions to be resoundingly devoid of meaning. The entire mystery of the secret cult at the center of the plot, with all its crude artifacts made of sticks, really only succeeds as a prop for Rust’s struggle with his own character. He needs something to obsess over. But the bad guy at the end, the monster at the end of the dream, is destined to disappoint. I included my own true detective in The Fire Hoarder so there would be someone who could explain why not finding such monsters is worse than finding them. And I went on to explore what a character like Rust, obsessive, brilliant, skeptical, curious, and haunted would do in the absence of a bad guy to hunt down. But my guy wouldn’t take himself so seriously.

If you add in the free indirect style of narration I enjoy in the works of Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Ian McEwan, Hilary Mantel, and others, along with some of the humor you find in their novels, you have the technique I used, the tone I tried to strike, and my approach to dealing with the themes. (The revelation at the end that one of the characters is acting as the narrator is a trick I’m most familiar with from McEwan’s Sweet Tooth.) The ideal reader response to my story would focus on these issues of style and technique, and insofar as the comments took on topics like the vividness of the characters or the feelings they inspired it would do so as if they were entities entirely separate from me and the people I know and care about.

But I know that would be asking a lot. The urge to read stories, the pleasure we take in them, is a product of the same instincts that make us fascinated with gossip. And we have a nasty tendency to try to find hidden messages in what we read, as though we were straining to hear the whispers we can’t help suspecting are about us--and not exactly flattering. So, as frustrated as I get with people who get the wrong idea, I usually come around to just being happy there are some people out there who are interested enough in what I’m doing to read my fiction.

Also read:

THE FIRE HOARDER

And:

SABBATH SAYS: PHILIP ROTH AND THE DILEMMAS OF IDEOLOGICAL CASTRATION

The Rowling Effect: The Uses and Abuses of Storytelling in Literary Fiction

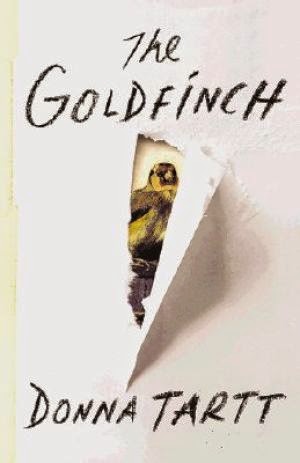

Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer-winning novel “The Goldfinch” prompted critic James Wood to lament the demise of the more weighty and serious novels of the past and the rise of fantastical stories in a world where adults go around reading Harry Potter. But is Wood confused about what storytelling really is?

It’s in school that almost everyone first experiences both the joys and the difficulties of reading stories. And almost everyone quickly learns to associate reading fiction with all the other abstract, impersonal, and cognitively demanding tasks forced on them by their teachers. One of the rewards of graduation, indeed of adulthood, is that you no longer have to read boring stories and novels you have to work hard to understand, all those lengthy texts that repay the effort with little else besides the bragging rights for having finished. (So, on top of being a waste of time, reading books makes normal people hate you.) One of the worst fates for an author, meanwhile, is to have your work assigned in one of those excruciating lit courses students treat as way stations on their way to gainful employment, an honor all but guaranteed to inspire lifelong loathing.

As a lonely endeavor, reading is most enticing—for many it’s only enticing—when viewed as an act of rebellion. (It’s no accident that the Harry Potter books begin with scenes of life with the Dursley family, caricaturizing as it does conformity and harsh, arbitrary discipline.) So, if students’ sole motivation to read comes from on-high, with the promise of quizzes and essays to follow, the natural defiance of adolescence ensures a deep-seated suspicion of the true purpose of the assignment and a stubborn resistance to any emotional connection with the characters. This is why all but the tamest, most credulous of students get filtered out on the way to advanced literature courses at universities, the kids neediest of praise from teachers and least capable of independent thought, which is in turn why so many cockamamie ideas proliferate in English departments. As arcane theories about the “indeterminacy of meaning” or “the author function” trickle down into high schools and grade schools, it becomes ever more difficult to imagine, let alone test, possible reforms to the methods teachers use to introduce kids to written stories.

Miraculously, reading persists at the margins of society, far removed from the bloodless academic exercises students are programmed to dread. The books you’re most likely to read after graduation are the type you read when you’re supposed to be reading something else, the comics tucked inside textbooks, the unassigned or outright banned books featuring characters struggling with sex, religious doubt, violence, abortion, or corrupt authorities. One of the reasons the market for books written for young adults is currently so vibrant and successful is that literature teachers haven’t gotten around to including any of the most recent novels in their syllabuses. And, if teachers take to heart the admonitions of critics like Ruth Graham, who insists that “the emotional and moral ambiguity of adult fiction—of the real world—is nowhere in evidence in YA fiction,” they never will. YA books' biggest success is making reading its own reward, not an exercise in the service of developing knowledge or character or maturity—whatever any of those are supposed to be. And what naysayers like Graham fear is that such enjoyment might be coming at the expense of those same budding virtues, and it may even forestall the reader’s graduation to the more refined gratifications that come from reading more ambiguous and complex—or more difficult, or less fantastical—fiction.

Harry Potter became a cultural phenomenon at a time when authors, publishers, and critics were busy breaking the news of the dismal prognosis for the novel, beset as it was by the rise of the internet, the new golden age of television, and a growing impatience with texts extending more than a few paragraphs. The impact may not have been felt in the wider literary world if the popularity of Rowling’s books had been limited to children and young adults, but British and American grownups seem to have reasoned that if the youngsters think it’s cool it’s probably worth it for the rest of us young-at-hearts to take a look. Now not only are adults reading fiction written for teens, but authors—even renowned literary authors—are taking their cue from the YA world. Marquee writers like Donna Tartt and David Mitchell are spinning out elaborate yarns teeming with teen-tested genre tropes they hope to make respectable with a liberal heaping of highly polished literary prose. Predictably, the laments and jeremiads from old-school connoisseurs are beginning to show up in high-end periodicals. Here’s James Wood’s opening to a review of Mitchell’s latest novel:

As the novel’s cultural centrality dims, so storytelling—J.K. Rowling’s magical Owl of Minerva, equipped for a thousand tricks and turns—flies up and fills the air. Meaning is a bit of a bore, but storytelling is alive. The novel form can be difficult, cumbrously serious; storytelling is all pleasure, fantastical in its fertility, its ceaseless inventiveness. Easy to consume, too, because it excites hunger while simultaneously satisfying it: we continuously want more. The novel now aspires to the regality of the boxed DVD set: the throne is a game of them. And the purer the storytelling the better—where purity is the embrace of sheer occurrence, unburdened by deeper meaning. Publishers, readers, booksellers, even critics, acclaim the novel that one can deliciously sink into, forget oneself in, the novel that returns us to the innocence of childhood or the dream of the cartoon, the novel of a thousand confections and no unwanted significance. What becomes harder to find, and lonelier to defend, is the idea of the novel as—in Ford Maddox Ford’s words—a “medium of profoundly serious investigation into the human case.”

As is customary for Wood, the bracingly eloquent clarifications in this passage serve to misdirect readers from its overall opacity, which is to say he raises more questions than he answers.

The most remarkable thing in Wood’s advance elegy (an idea right out of Tom Sawyer and reprised in The Fault in Our Stars) is the idea that “the novel” is somehow at odds with storytelling. The charge that a given novel fails to rise above mere kitsch is often a legitimate one: a likable but attractively flawed character meets another likable character whose equally attractive flaws perfectly complement and compensate for those of the first, so that they can together transcend their foibles and live happily ever after. This is the formula for commercial fiction, designed to uplift and delight (and make money). But the best of YA novels are hardly guilty of this kind of pandering. And even if we acknowledge that an author aiming simply to be popular and pleasing is a good formula in its own right—for crappy novels—it doesn’t follow that quality writing precludes pleasurable reading. The questions critics like Graham and Wood fail to answer as they bemoan the decline of ambiguity on the one hand and meaning on the other is what role either one of them naturally plays, either in storytelling or in literature, and what really distinguishes a story from a supposedly more serious and meaningful novel?

Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer-winning novel The Goldfinch has rekindled an old debate about the difference between genre fiction and serious literature. Evgenia Peretz chronicles some earlier iterations of the argument in Vanity Fair, and the popularity of Rowling’s wizards keeps coming up, both as an emblem of the wider problem and a point of evidence proving its existence. As Christopher Beha explains in the New Yorker,

The problem with “The Goldfinch,” its detractors said, was that it was essentially a Y.A. novel. Vanity Fair quoted Wood as saying that “the rapture with which this novel has been received is further proof of the infantilization of our literary culture: a world in which adults go around reading Harry Potter.

For Wood—and he’s hardly alone—fantastical fiction lacks meaning for the very reason so many readers find it enjoyable: it takes place in a world that simply doesn’t exist, with characters like no one you’ll ever really encounter, and the plots resolve in ways that, while offering some modicum of reassurance and uplift, ultimately mislead everyone about what real, adult life is all about. Whatever meaning these simplified and fantastical fictions may have is thus hermetically sealed within the world of the story.

The terms used in the debates over whether there’s a meaningful difference between commercial and literary fiction and whether adults should be embarrassed to be caught reading Harry Potter are so poorly defined, and the nature of stories so poorly understood, that it seems like nothing will ever be settled. But the fuzziness here is gratuitous. Graham’s cherishing of ambiguity is perfectly arbitrary. Wood is simply wrong in positing a natural tension between storytelling and meaning. And these critics’ gropings after some solid feature of good, serious, complex, adult literature they can hold up to justify their impatience and disappointment in less ambitious readers is symptomatic of the profound vacuity of literary criticism as both a field of inquiry and an artistic, literary form of its own. Even a critic as erudite and perceptive as Wood—and as eminently worth reading, even when he’s completely wrong—relies on fundamental misconceptions about the nature of stories and the nature of art.

For Wood, the terms story, genre, plot, and occurrence are all but interchangeable. That’s how he can condemn “the embrace of sheer occurrence, unburdened by deeper meaning.” But the type of meaning he seeks in literature sounds a lot like philosophy or science. How does he distinguish between novels and treatises? The problem here is that story is not reducible to sheer occurrence. Plots are not mere sequences of events. If I tell you I got in my car, went to the store, and came home, I’m recalling a series of actions—but it’s hardly a story. However, if I say I went to the store and while I was there I accidentally bumped shoulders with a guy who immediately flew into a rage, then I’ve begun to tell you a real story. Many critics and writing coaches characterize this crucial ingredient as conflict, but that’s only partly right. Conflicts can easily be reduced to a series of incidents. What makes a story a story is that it features some kind of dilemma, some situation in which the protagonist has to make a difficult decision. Do I risk humiliation and apologize profusely to the guy whose shoulder I bumped? Do I risk bodily harm and legal trouble by standing up for myself? There’s no easy answer. That’s why it has the makings of a good story.

Meaning in stories is not declarative or propositional, just as the point of physical training doesn’t lie in any communicative aspect of the individual exercises. And you wouldn’t judge a training regimen based solely on the exercises’ resemblance to actions people perform in their daily lives. A workout is good if it’s both enjoyable and effective, that is, if going through it offers sufficient gratification to outweigh the difficulty—so you keep doing it—and if you see improvements in the way you look and feel. The pleasure humans get from stories is probably a result of the same evolutionary processes that make play fighting or play stalking fun for cats and dogs. We need to acquire skills for handling our complex social lives just as they need to acquire skills for fighting and hunting. Play is free-style practice made pleasurable by natural selection to ensure we’re rewarded for engaging in it. The form that play takes, as important as it is in preparing for real-life challenges, only needs to resemble real life enough for the skills it hones to be applicable. And there’s no reason reading about Harry Potter working through his suspicions and doubts about Dumbledore couldn’t help to prepare people of any age for a similar experience of having to question the wisdom or trustworthiness of someone they admire—even though they don’t know any wizards. (And isn’t this dilemma similar to the one so many of Saul Bellow’s characters face in dealing with their “reality instructors” in the novels Wood loves most?)

The rather obvious principle that gets almost completely overlooked in debates about low versus high art is that the more refined and complex a work is the more effort will be necessary to fully experience it and the fewer people will be able to fully appreciate it. The exquisite pleasures of long-distance running, or classical music, or abstract art are reserved for those who have done adequate training and acquired sufficient background knowledge. Apart from this inescapable corollary of aesthetic refinement and sophistication, though, there’s a fetishizing of difficulty for the sake of difficulty apparent in many art forms. In literature, novels celebrated by the supposed authorities, books like Ulysses, Finnegan’s Wake, and Infinite Jest, offer none of the joys of good stories. Is it any wonder so many readers have stopped listening to the authorities? Wood is not so foolish as to equate difficulty with quality, as fans of Finnegan’s Wake must, but he does indeed make the opposite mistake—assuming that lack of difficulty proves lack of quality. There’s also an unmistakable hint of the puritanical, even the masochistic in Wood’s separation of the novel from storytelling and its pleasures. He’s like the hulking power lifter overcome with disappointment at all the dilettantish fitness enthusiasts parading around the gym, smiling, giggling, not even exerting themselves enough to feel any real pain.

What the Harry Potter books are telling us is that there still exists a real hunger for stories, not just as flippant and senseless contrivances, but as rigorously imagined moral dilemmas faced by characters who inspire strong feelings, whether positive, negative, or ambivalent. YA fiction isn't necessarily simpler, its characters invariably bland baddies or goodies, its endings always neat and happy. The only things that reliably distinguish it are its predominantly young adult characters and its general accessibility. It's probably true that The Goldfinch's appeal to many people derives from it being both literary and accessible. More interestingly, it probably turns off just as many people, not because it's overplotted, but because the story is mediocre, the central dilemma of the plot too easily resolved, the main character too passive and pathetic. Call me an idealist, but I believe that literary language can be challenging while not being impenetrable, that plots can be both eventful and meaningful, and that there’s a reliable blend of ingredients for mixing this particular magic potion: characters who actually do things, whose actions get them mixed up in high-stakes dilemmas, who are described in language that both captures their personalities and conveys the urgency of their circumstances. This doesn’t mean every novel needs to have dragons and werewolves, but it does mean having them doesn’t necessarily make a novel unworthy of serious attention from adults. And we need not worry about the fate of less fantastical literature because there will always be a small percentage of the population who prefers, at least on occasion, a heavier lift.

Also read:

And:

LET'S PLAY KILL YOUR BROTHER: FICTION AS A MORAL DILEMMA GAME

And:

How Violent Fiction Works: Rohan Wilson’s “The Roving Party” and James Wood’s Sanguinary Sublime from Conrad to McCarthy

James Wood criticized Cormac McCathy’s “No Country for Old Men” for being too trapped by its own genre tropes. Wood has a strikingly keen eye for literary registers, but he’s missing something crucial in his analysis of McCarthy’s work. Rohan Wilson’s “The Roving Party” works on some of the same principles as McCarthy’s work, and it shows that the authors’ visions extend far beyond the pages of any book.

Any acclaimed novel of violence must be cause for alarm to anyone who believes stories encourage the behaviors depicted in them or contaminate the minds of readers with the attitudes of the characters. “I always read the book as an allegory, as a disguised philosophical argument,” writes David Shields in his widely celebrated manifesto Reality Hunger. Suspicious of any such disguised effort at persuasion, Shields bemoans the continuing popularity of traditional novels and agitates on behalf of a revolutionary new form of writing, a type of collage that is neither marked as fiction nor claimed as truth but functions rather as a happy hybrid—or, depending on your tastes, a careless mess—and is in any case completely lacking in narrative structure. This is because to him giving narrative structure to a piece of writing is itself a rhetorical move. “I always try to read form as content, style as meaning,” Shields writes. “The book is always, in some sense, stutteringly, about its own language” (197).

As arcane as Shields’s approach to reading may sound, his attempt to find some underlying message in every novel resonates with the preoccupations popular among academic literary critics. But what would it mean if novels really were primarily concerned with their own language, as so many students in college literature courses are taught? What if there really were some higher-order meaning we absorbed unconsciously through reading, even as we went about distracting ourselves with the details of description, character, and plot? Might a novel like Heart of Darkness, instead of being about Marlowe’s growing awareness of Kurtz’s descent into inhuman barbarity, really be about something that at first seems merely contextual and incidental, like the darkness—the evil—of sub-Saharan Africa and its inhabitants? Might there be a subtle prompt to regard Kurtz’s transformation as some breed of enlightenment, a fatal lesson encapsulated and propagated by Conrad’s fussy and beautifully tantalizing prose, as if the author were wielding the English language like the fastenings of a yoke over the entire continent?

Novels like Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and, more recently, Rohan Wilson’s The Roving Party, take place amid a transition from tribal societies to industrial civilization similar to the one occurring in Conrad’s Congo. Is it in this seeming backdrop that we should seek the true meaning of these tales of violence? Both McCarthy’s and Wilson’s novels, it must be noted, represent conspicuous efforts at undermining the sanitized and Manichean myths that arose to justify the displacement and mass killing of indigenous peoples by Europeans as they spread over the far-flung regions of the globe. The white men hunting “Indians” for the bounties on their scalps in Blood Meridian are as beastly and bloodthirsty as the savages peopling the most lurid colonial propaganda, just as the Europeans making up Wilson’s roving party are only distinguishable by the relative degrees of their moral degradation, all of them, including the protagonist, moving in the shadow of their chief quarry, a native Tasmanian chief.

If these novels are about their own language, their form comprising their true content, all in the service of some allegory or argument, then what pleasure would anyone get from them, suggesting as they do that to partake of the fruit of civilization is to become complicit in the original sin of the massacre that made way for it? “There is no document of civilization,” Walter Benjamin wrote, “that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” It could be that to read these novels is to undergo a sort of rite of expiation, similar to the ritual reenactment of the crucifixion performed by Christians in the lead up to Easter. Alternatively, the real argument hidden in these stories may be still more insidious; what if they’re making the case that violence is both eternal and unavoidable, that it is in our nature to relish it, so there’s no more point in resisting the urge personally than in trying to bring about reform politically?

Shields intimates that the reason we enjoy stories is that they warrant our complacency when he writes, “To ‘tell a story well’ is to make what one writes resemble the schemes people are used to—in other words, their ready-made idea of reality” (200). Just as we take pleasure in arguments for what we already believe, Shields maintains (explicitly) that we delight in stories that depict familiar scenes and resolve in ways compatible with our convictions. And this equating of the pleasure we take in reading with the pleasure we take in having our beliefs reaffirmed is another practice nearly universal among literary critics. Sophisticated readers know better than to conflate the ideas professed by villainous characters like the judge in Blood Meridian with those of the author, but, as one prominent critic complains,

there is often the disquieting sense that McCarthy’s fiction puts certain fond American myths under pressure merely to replace them with one vaster myth—eternal violence, or [Harold] Bloom’s “universal tragedy of blood.” McCarthy’s fiction seems to say, repeatedly, that this is how it has been and how it always will be.

What’s interesting about this interpretation is that it doesn’t come from anyone normally associated with Shields’s school of thought on literature. Indeed, its author, James Wood, is something of a scourge to postmodern scholars of Shields’s ilk.

Wood takes McCarthy to task for his alleged narrative dissemination of the myth of eternal violence in a 2005 New Yorker piece, Red Planet: The Sanguinary Sublime of Cormac McCarthy, a review of his then latest novel No Country for Old Men. Wood too, it turns out, hungers for reality in his novels, and he faults McCarthy’s book for substituting psychological profundity with the pabulum of standard plot devices. He insists that

the book gestures not toward any recognizable reality but merely toward the narrative codes already established by pulp thrillers and action films. The story is itself cinematically familiar. It is 1980, and a young man, Llewelyn Moss, is out antelope hunting in the Texas desert. He stumbles upon several bodies, three trucks, and a case full of money. He takes the money. We know that he is now a marked man; indeed, a killer named Anton Chigurh—it is he who opens the book by strangling the deputy—is on his trail.

Because McCarthy relies on the tropes of a familiar genre to convey his meaning, Wood suggests, that meaning can only apply to the hermetic universe imagined by that genre. In other words, any meaning conveyed in No Country for Old Men is rendered null in transit to the real world.

When Chigurh tells the blameless Carla Jean that “the shape of your path was visible from the beginning,” most readers, tutored in the rhetoric of pulp, will write it off as so much genre guff. But there is a way in which Chigurh is right: the thriller form knew all along that this was her end.

The acuity of Wood’s perception when it comes to the intricacies of literary language is often staggering, and his grasp of how diction and vocabulary provide clues to the narrator’s character and state of mind is equally prodigious. But, in this dismissal of Chigurh as a mere plot contrivance, as in his estimation of No Country for Old Men in general as a “morally empty book,” Wood is quite simply, quite startlingly, mistaken. And we might even say that the critical form knew all along that he would make this mistake.

When Chigurh tells Carla Jean her path was visible, he’s not voicing any hardboiled fatalism, as Wood assumes; he’s pointing out that her predicament came about as a result of a decision her husband Llewelyn Moss made with full knowledge of the promised consequences. And we have to ask, could Wood really have known, before Chigurh showed up at the Moss residence, that Carla Jean would be made to pay for her husband’s defiance? It’s easy enough to point out superficial similarities to genre conventions in the novel (many of which it turns inside-out), but it doesn’t follow that anyone who notices them will be able to foretell how the book will end. Wood, despite his reservations, admits that No Country for Old Men is “very gripping.” But how could it be if the end were so predictable? And, if it were truly so morally empty, why would Wood care how it was going to end enough to be gripped? Indeed, it is in the realm of the characters’ moral natures that Wood is the most blinded by his reliance on critical convention. He argues,

Lewelyn Moss, the hunted, ought not to resemble Anton Chigurh, the hunter, but the flattening effect of the plot makes them essentially indistinguishable. The reader, of course, sides with the hunted. But both have been made unfree by the fake determinism of the thriller.

How could the two men’s fates be determined by the genre if in a good many thrillers the good guy, the hunted, prevails?

One glaring omission in Wood’s analysis is that Moss initially escapes undetected with the drug money he discovers at the scene of the shootout he happens upon while hunting, but he is then tormented by his conscience until he decides to return to the trucks with a jug of water for a dying man who begged him for a drink. “I’m fixin to go do somethin dumbern hell but I’m goin anyways,” he says to Carla Jean when she asks what he’s doing. “If I don’t come back tell Mother I love her” (24). Llewelyn, throughout the ensuing chase, is thus being punished for doing the right thing, an injustice that unsettles readers to the point where we can’t look away—we’re gripped—until we’re assured that he ultimately defeats the agents of that injustice. While Moss risks his life to give a man a drink, Chigurh, as Wood points out, is first seen killing a cop. Moreover, it’s hard to imagine Moss showing up to murder an innocent woman to make good on an ultimatum he’d presented to a man who had already been killed in the interim—as Chigurh does in the scene when he explains to Carla Jean that she’s to be killed because Llewelyn made the wrong choice.

Chigurh is in fact strangely principled, in a morally inverted sort of way, but the claim that he’s indistinguishable from Moss bespeaks a failure of attention completely at odds with the uncannily keen-eyed reading we’ve come to expect from Wood. When he revisits McCarthy’s writing in a review of the 2006 post-apocalyptic novel The Road, collected in the book The Fun Stuff, Wood is once again impressed by McCarthy’s “remarkable effects” but thoroughly baffled by “the matter of his meanings” (61). The novel takes us on a journey south to the sea with a father and his son as they scrounge desperately for food in abandoned houses along the way. Wood credits McCarthy for not substituting allegory for the answer to “a simpler question, more taxing to the imagination and far closer to the primary business of fiction making: what would this world without people look like, feel like?” But then he unaccountably struggles to sift out the novel’s hidden philosophical message. He writes,

A post-apocalyptic vision cannot but provoke dilemmas of theodicy, of the justice of fate; and a lament for the Deus absconditus is both implicit in McCarthy’s imagery—the fine simile of the sun that circles the earth “like a grieving mother with a lamp”—and explicit in his dialogue. Early in the book, the father looks at his son and thinks: “If he is not the word of God God never spoke.” There are thieves and murderers and even cannibals on the loose, and the father and son encounter these fearsome envoys of evil every so often. The son needs to think of himself as “one of the good guys,” and his father assures him that this is the side they are indeed on. (62)

We’re left wondering, is there any way to answer the question of what a post-apocalypse would be like in a story that features starving people reduced to cannibalism without providing fodder for genre-leery critics on the lookout for characters they can reduce to mere “envoys of evil”?

As trenchant as Wood is regarding literary narration, and as erudite—or pedantic, depending on your tastes—as he is regarding theology, the author of the excellent book How Fiction Works can’t help but fall afoul of his own, and his discipline’s, thoroughgoing ignorance when it comes to how plots work, what keeps the moral heart of a story beating. The way Wood fails to account for the forest comprised of the trees he takes such thorough inventory of calls to mind a line of his own from a chapter in The Fun Stuff about Edmund Wilson, describing an uncharacteristic failure on part of this other preeminent critic:

Yet the lack of attention to detail, in a writer whose greatness rests supremely on his use of detail, the unwillingness to talk of fiction as if narrative were a special kind of aesthetic experience and not a reducible proposition… is rather scandalous. (72)

To his credit, though, Wood never writes about novels as if they were completely reducible to their propositions; he doesn’t share David Shields’s conviction that stories are nothing but allegories or disguised philosophical arguments. Indeed, few critics are as eloquent as Wood on the capacity of good narration to communicate the texture of experience in a way all literate people can recognize from their own lived existences.

But Wood isn’t interested in plot. He just doesn’t seem to like them. (There’s no mention of plot in either the table of contents or the index to How Fiction Works.) Worse, he shares Shields’s and other postmodern critics’ impulse to decode plots and their resolutions—though he also searches for ways to reconcile whatever moral he manages to pry from the story with its other elements. This is in fact one of the habits that tends to derail his reviews. Even after lauding The Road’s eschewal of easy allegory in place of the hard work of ground-up realism, Wood can’t help trying to decipher the end of the novel in the context of the religious struggle he sees taking place in it. He writes of the son’s survival,

The boy is indeed a kind of last God, who is “carrying the fire” of belief (the father and son used to speak of themselves, in a kind of familial shorthand, as people who were carrying the fire: it seems to be a version of being “the good guys”.) Since the breath of God passes from man to man, and God cannot die, this boy represents what will survive of humanity, and also points to how life will be rebuilt. (64)

This interpretation underlies Wood’s contemptuous attitude toward other reviewers who found the story uplifting, including Oprah, who used The Road as one of her book club selections. To Wood, the message rings false. He complains that

a paragraph of religious consolation at the end of such a novel is striking, and it throws the book off balance a little, precisely because theology has not seemed exactly central to the book’s inquiry. One has a persistent, uneasy sense that theodicy and the absent God have been merely exploited by the book, engaged with only lightly, without much pressure of interrogation. (64)